|

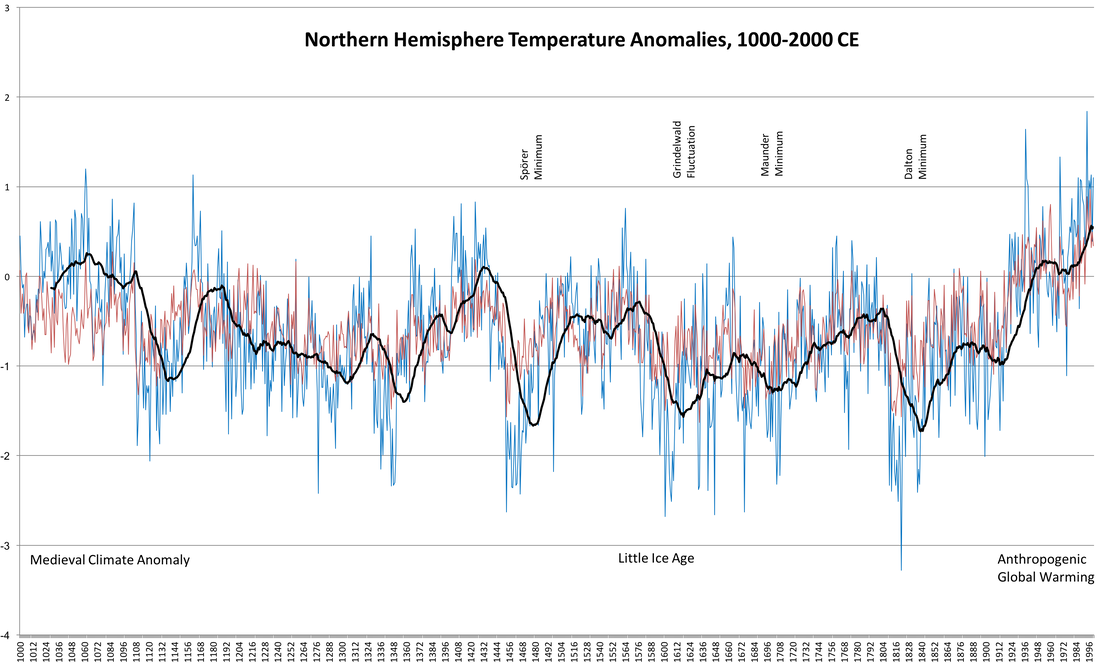

Prof. Dagomar Degroot, Georgetown University. Roughly 11,000 years ago, rising sea levels submerged Beringia, the vast land bridge that once connected the Old and New Worlds. Vikings and perhaps Polynesians briefly established a foothold in the Americas, but it was the voyage of Columbus in 1492 that firmly restored the ancient link between the world’s hemispheres. Plants, animals, and pathogens – the microscopic agents of disease – never before seen in the Americas now arrived in the very heart of the western hemisphere. It is commonly said that few organisms spread more quickly, or with more horrific consequences, than the microbes responsible for measles and smallpox. Since the original inhabitants of the Americas had never encountered them before, millions died. The great environmental historian Alfred Crosby first popularized these ideas in 1972. It took over thirty years before a climatologist, William Ruddiman, added a disturbing new wrinkle. What if so many people died so quickly across the Americas that it changed Earth’s climate? Abandoned fields and woodlands, once carefully cultivated, must have been overrun by wild plants that would have drawn huge amounts of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. Perhaps that was the cause of a sixteenth-century drop in atmospheric carbon dioxide, which scientists had earlier uncovered by sampling ancient bubbles in polar ice sheets. By weakening the greenhouse effect, the drop might have exacerbated cooling already underway during the “Grindelwald Fluctuation:” an especially frigid stretch of a much older cold period called the “Little Ice Age." Last month, an extraordinary article by a team of scholars from the University College London captured international headlines by uncovering new evidence for these apparent relationships. The authors calculate that nearly 56 million hectares previously used for food production must have been abandoned in just the century after 1492, when they estimate that epidemics killed 90% of the roughly 60 million people indigenous to the Americas. They conclude that roughly half of the simultaneous dip in atmospheric carbon dioxide cannot be accounted for unless wild plants grew rapidly across these vast territories. On social media, the article went viral at a time when the Trump Administration’s wanton disregard for the lives of Latin American refugees seems matched only by its contempt for climate science. For many, the links between colonial violence and climate change never appeared clearer – or more firmly rooted in the history of white supremacy. Some may wonder whether it is wise to quibble with science that offers urgently-needed perspectives on very real, and very alarming, relationships in our present. Yet bold claims naturally invite questions and criticism, and so it is with this new article. Historians – who were not among the co-authors – may point out that the article relies on dated scholarship to calculate the size of pre-contact populations in the Americas, and the causes for their decline. Newer work has in fact found little evidence for pan-American pandemics before the seventeenth century. More importantly, the article’s headline-grabbing conclusions depend on a chain of speculative relationships, each with enough uncertainties to call the entire chain into question. For example, some cores exhumed from Antarctic ice sheets appear to reveal a gradual decline in atmospheric carbon dioxide during the sixteenth century, while others apparently show an abrupt fall around 1590. Part of the reason may have to do with local atmospheric variations. Yet the difference cannot be dismissed, since it is hard to imagine how gradual depopulation could have led to an abrupt fall in 1590. To take another example, the article leans on computer models and datasets that estimate the historical expansion of cropland and pasture. Models cited in the article suggest that the area under human cultivation steadily increased from 1500 until 1700: precisely the period when its decline supposedly cooled the Earth. An increase would make sense, considering that the world’s human population likely rose by as many as 100 million people over the course of the sixteenth century. Meanwhile, merchants and governments across Eurasia depleted woodlands to power new industries and arm growing militaries. Changes in the extent and distribution of historical cropland, 3000 BCE to the present, according to the HYDE 3.1 database of human-induced global land use change. In any case, models and datasets may generate tidy numbers and figures, but they are by nature inexact tools for an era when few kept careful or reliable track of cultivated land. Models may differ enormously in their simulations of human land use; one, for example, shows 140 million more hectares of cropland than another for the year 1700. Remember that, according to the new article, the abandonment of just 56 million hectares in the Americas supposedly cooled the planet just a century earlier! If we can make educated guesses about land use changes across Asia or Europe, we know next to nothing about what might have happened in sixteenth-century Africa. Demographic changes across that vast and diverse continent may well have either amplified or diminished the climatic impact of depopulation in the Americas. And even in the Americas, we cannot easily model the relationship between human populations and land use. Surging populations of animals imported by Europeans, for example, may have chewed through enough plants to hold off advancing forests. Moreover, the early death toll in the Americas was often also especially high in communities at high elevations: where the tropical trees that absorb the most carbon could not go. In short, we cannot firmly establish that depopulation in the Americas cooled the Earth. For that reason, it is missing the point to think of the new article as either “wrong” or “right;” rather, we should view it as a particularly interesting contribution to an ongoing academic conversation. Journalists in particular should also avoid exaggerating the article’s conclusions. The co-authors never claim, for example, that depopulation “caused” the Little Ice Age, as some headlines announced, nor even the Grindelwald Fluctuation. At most, it worsened cooling already underway during that especially frigid stretch of the Little Ice Age. For all the enduring questions it provokes, the new article draws welcome attention to the enormity of what it calls the “Great Dying” that accompanied European colonization, which was really more of a “Great Killing” given the deliberate role that many colonizers played in the disaster. It also highlights the momentous environmental changes that accompanied the European conquest. The so-called “Age of Exploration” linked not only the Americas but many previously isolated lands to the Old World, in complex ways that nevertheless reshaped entire continents to look more like Europe. We are still reckoning with and contributing to the resulting, massive decline in plant and animal biomass and diversity. Not for nothing do some date the “Anthropocene,” the proposed geological epoch distinguished by human dominion over the natural world, to the sixteenth century. All of these issues also shed much-needed light on the Little Ice Age. Whatever its cause, we now know that climatic cooling had profound consequences for contemporary societies. Cooling and associated changes in atmospheric and oceanic circulation provoked harvest failures that all too often resulted in famines. In community after community, the malnourished repeatedly fell victim to outbreaks of epidemic disease, and mounting misery led many to take up arms against contemporary governments. Some communities and societies were resilient, even adaptive in the face of these calamities, but often partly by taking advantage of the less fortunate. Whether or not the New World genocide led to cooling, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries offer plenty of warnings for our time. My thanks to Georgetown environmental historians John McNeill and Timothy Newfield for their help with this article, to paleoclimatologist Jürg Luterbacher for answering my questions about ice cores, and to colleagues who responded to my initial reflections on social media. Works Cited:

Archer, S. "Colonialism and Other Afflictions: Rethinking Native American Health History." History Compass 14 (2016): 511-21. Crosby, Alfred W. “Conquistador y pestilencia: the first New World pandemic and the fall of the great Indian empires.” The Hispanic American Historical Review 47:3 (1967): 321-337. Crosby, Alfred W. The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1972. Alfred W. Crosby, Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900-1900, 2nd Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. Degroot, Dagomar. “Climate Change and Society from the Fifteenth Through the Eighteenth Centuries.” WIREs Climate Change Advanced Review. DOI:10.1002/wcc.518 Degroot, Dagomar. The Frigid Golden Age: Climate Change, the Little Ice Age, and the Dutch Republic, 1560-1720. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018. Gade, Daniel W. “Particularizing the Columbian exchange: Old World biota to Peru.” Journal of Historical Geography 48 (2015): 30. Goldewijk, Kees Klein, Arthur Beusen, Gerard Van Drecht, and Martine De Vos, “The HYDE 3.1 spatially explicit database of human‐induced global land‐use change over the past 12,000 years.” Global Ecology and Biogeography 20:1 (2011): 73-86. Jones, Emily Lena. “The ‘Columbian Exchange’ and landscapes of the Middle Rio Grande Valley, AD 1300– 1900.” The Holocene (2015): 1704. Kelton, Paul. "The Great Southeastern Smallpox Epidemic, 1696-1700: The Region's First Major Epidemic?". In R. Ethridge and C. Hudson, eds., The Transformation of Southeastern Indians, 1540-1760. Koch, Alexander, Chris Brierley, Mark M. Maslin, and Simon L. Lewis. “Earth system impacts of the European arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492.” Quaternary Science Reviews 207 (2019): 13-36 McCook, Stuart. “The Neo-Columbian Exchange: The Second Conquest of the Greater Caribbean, 1720-1930.” Latin American Research Review 46: 4 (2011): 13. McNeill, J. R. “Woods and Warfare in World History.” Environmental History, 9:3 (2004): 388-410. Melville, Elinor G. K. A Plague of Sheep: Environmental Consequences of the Conquest of Mexico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997. PAGES2k Consortium, “A global multiproxy database for temperature reconstructions of the Common Era.” Scientific Data 4 (2017). doi:10.1038/sdata.2017.88. Parker, Geoffrey. Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013. Sigl, Michael et al., "Timing and climate forcing of volcanic eruptions for the past 2,500 years." Nature 523:7562 (2015): 543. Riley, James C. "Smallpox and American Indians Revisited." Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 65 (2010): 445-77. Ruddiman, William. “The Anthropogenic Greenhouse Era Began Thousands of Years Ago.” Climatic Change 61 (2003): 261–93. Ruddiman, William. Plows, Plagues, and Petroleum: How Humans Took Control of Climate. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005 Williams, Michael. Deforesting the Earth: From Prehistory to Global Crisis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press., 2002.

I don't think so. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed