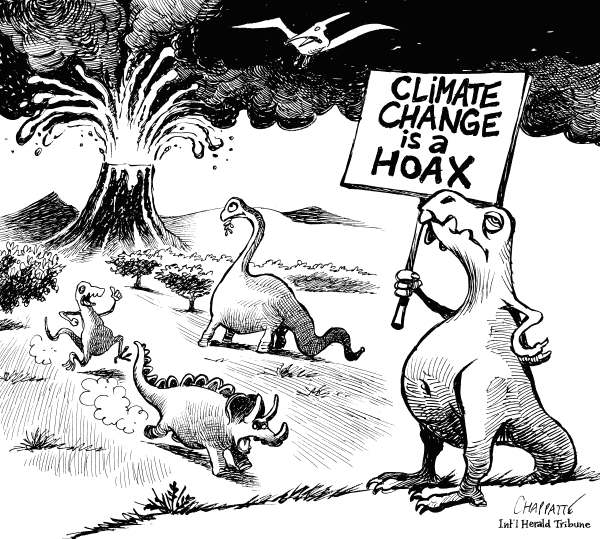

This site explores interdisciplinary research into climate changes past, present, and future. Its articles express my conviction that diverse approaches, methodologies, and findings can yield the most accurate perspectives on complex problems. To contextualize modern warming, for example, we can reconstruct past climate change using models developed by computer scientists; tree rings or ice cores examined by climatologists; and documents interpreted by historians. We gain far more by using these sources in concert than we would by examining each in isolation. Yet we must approach such interdisciplinarity with caution. The problems presented by climate change scepticism provide lessons for academics crossing disciplinary boundaries, and for policymakers, journalists, and laypeople interpreting interdisciplinary findings. In academia, climate change scepticism is usually interdisciplinary. To attack climate change research, academic sceptics use credibility and, occasionally, scholarly methods accrued in relevant disciplines but often unrelated fields. For example, in the late 1980s and 1990s, eminent physicists William Nierenberg and Fred Seitz were among the most outspoken critics of the global warming hypothesis. According to historians of science Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway, the scepticism expressed by Nierenberg and Seitz grew, in part, from their belief that the ends of supporting unfettered capitalism justified the means of deliberately distorting scientific evidence (Oreskes and Conway, 190). However, another part – perhaps the most damaging – emerged from the conviction that their disciplinary backgrounds gave them special insight into climate change research Physicists – including one of our own editors – play a crucial role in modelling and interpreting climate change. Yet not all physicists are alike. Nierenberg was a renowned nuclear physicist who oversaw the development of military and industrial technologies for exploiting the sea. Seitz developed one of the first quantum theories of crystals, and contributed to major innovations in solid-state physics. Owing to their similar academic backgrounds, both Nierenberg and Seitz distrusted the lack of certainty in climate modelling, and both would have despised the occasionally fuzzy probabilities that must accompany climate history. Their scepticism effectively takes the most tenuous elements of climate science and argues that they are not science, because “real scientists” know better. These attitudes highlight one of the most important but least appreciated aspects of interdisciplinary research: humility. When we step into another field, we step into another culture with characteristics that often have sound reasons for existing. Before challenging assumptions that inform a discipline, we should thoroughly learn the language, methods, and concepts of scholars in that discipline. Only then can we appreciate their findings. Climate scepticism can also reveal that differences between subfields within academic disciplines can be more significant than distinctions between those disciplines. An environmental historian, for instance, can have much more in common with a climatologist than a postmodern cultural historian. Another example: Fred Singer is an atmospheric physicist who played an important role in developing the first weather satellites. However, he has little respect for the methods or conclusions of mainstream climate research. In 2006, Singer told the CBC’s The Fifth Estate that “it was warmer a thousand years ago than it is today. Vikings settled Greenland. Is that good or bad? I think it's good.” In an interview with The Daily Telegraph three years later, he acknowledged that “we are certainly putting more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.” However, he argued that “there is no evidence that this high CO2 is making a detectable difference. It should in principle, however the atmosphere is very complicated and one cannot simply argue that just because CO2 is a greenhouse gas it causes warming.” Vikings did settle in Greenland, and the atmosphere is very complicated. However, global temperatures are warmer now than they were a millennium ago, and we can certainly trace relationships between modern warming and atmospheric concentrations of CO2. Singer may be an atmospheric physicist, but he is hardly qualified to offer any observations on the state of climate change research. Distinctions between different kinds of scientists – and different agendas among scientists – are always worth remembering when exploring the study of climate change. In a recent article, the popular website Reporting Climate Science described a disagreement between physical oceanographer Jochem Marotzke and meteorologist Piers Forster on the one hand, and “climate scientist” Nic Lewis on the other. Marotzke and Forster recently published an article in the journal Nature that confirmed the reliability of climate models for predicting climate change. Lewis accused them of circular reasoning and basic mathematical and statistical errors.

Lewis is, in fact, a retired financier with a degree in mathematics, and a minor in physics, from Cambridge University. Does that make him a climate scientist? He is certainly qualified to challenge mathematical approaches, and he does not deny the basic physics of anthropogenic climate change. For policymakers, journalists, and even scholars in different disciplines, it can be difficult to discern with what authority he speaks. Similar problems are at work in another recent academic debate. This one unfolded in the pages of the Journal of Interdisciplinary History. As described on this website, two economists took issue with the notion of a “Little Ice Age” between the fourteenth and nineteenth centuries. They waded into an established field – climate history – and assailed one of its most important themes – the existence of a Little Ice Age – without appreciating the methods and findings of recent scholarship. For example, they used a graph of early modern British grain prices as a direct proxy for contemporary changes in temperature. But those grain prices were influenced by so many human variables that, for modern scholars, they can, at best, suggest only how one society responded to climate change. While attacking the rigour of climate reconstructions, the economists actually introduced data that is far less rigorous than climate historians use today. Within academia, most instances of climate change scepticism are case studies of interdisciplinary approaches gone wrong. Interdisciplinarity can help us approach thorny issues in new ways, but such work should be collaborative. When adherents of one discipline or field dictate to those in another, the results are usually destructive. ~Dagomar Degroot Note: the cover photo was taken by our editor, Benoit Lecavalier, during a recent trip to Greenland. |

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed