|

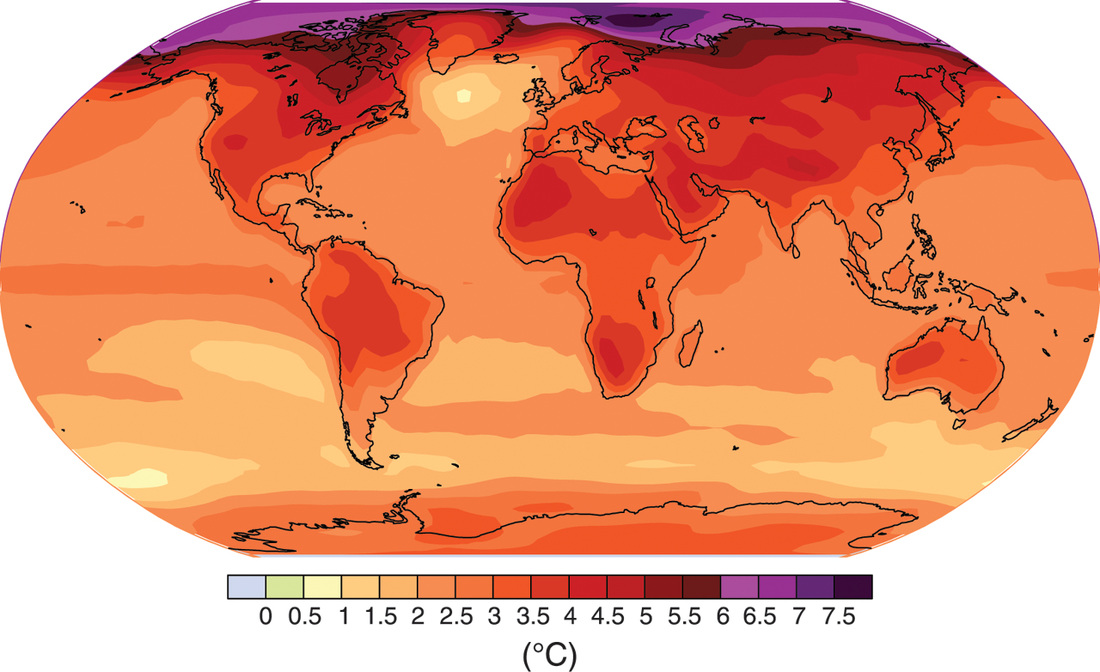

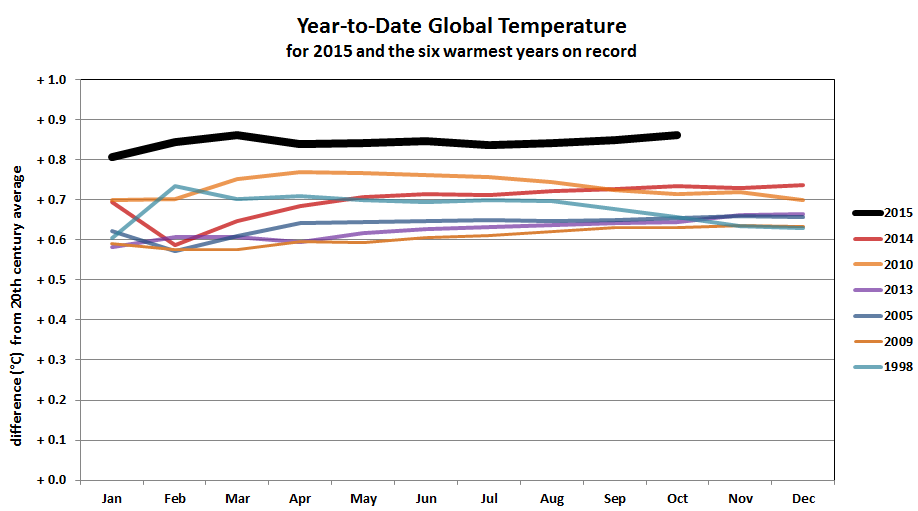

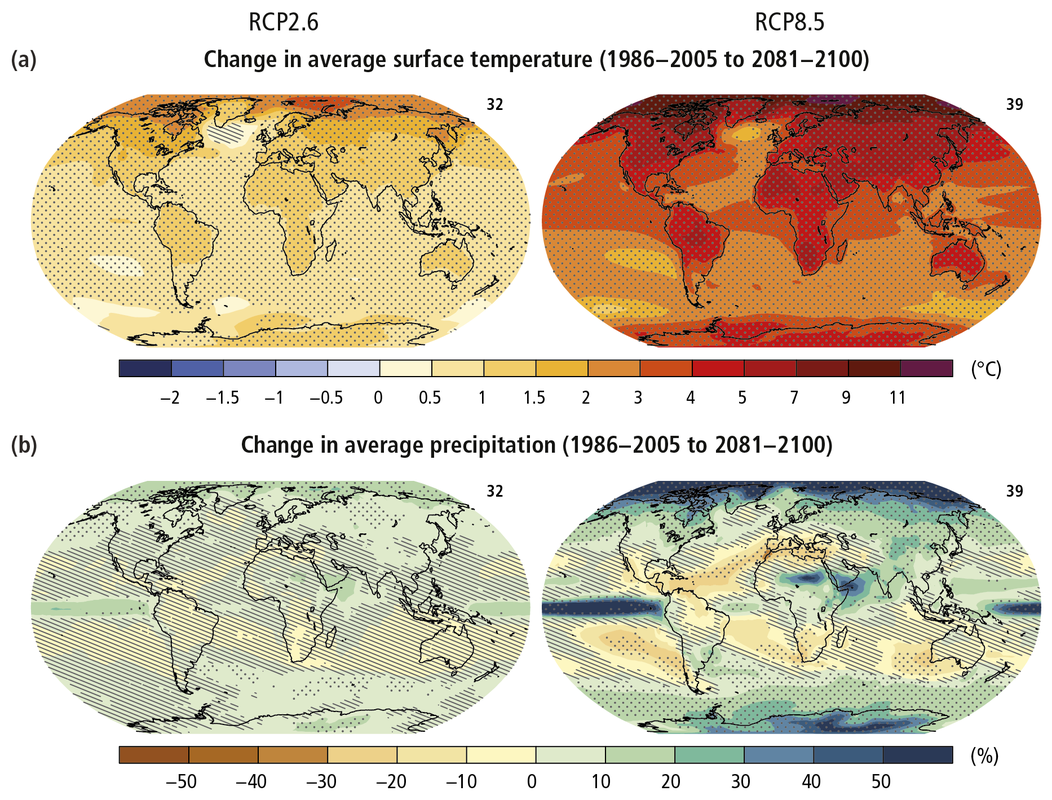

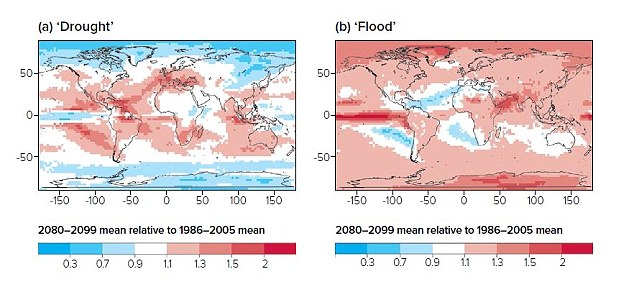

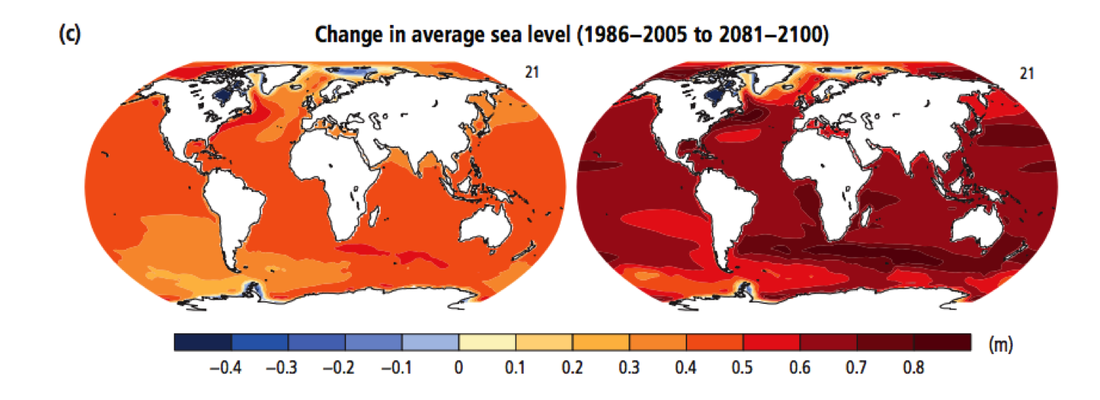

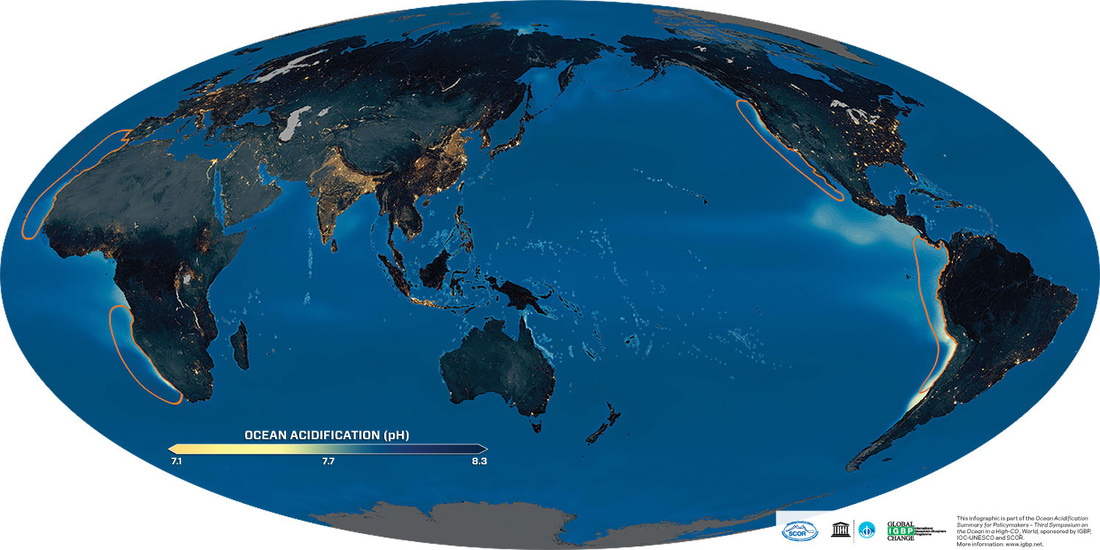

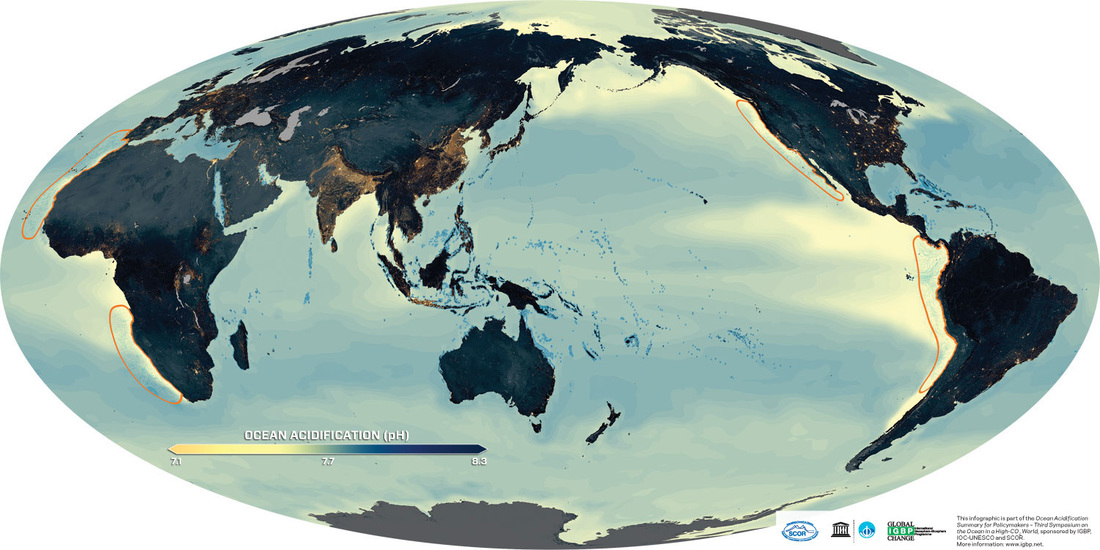

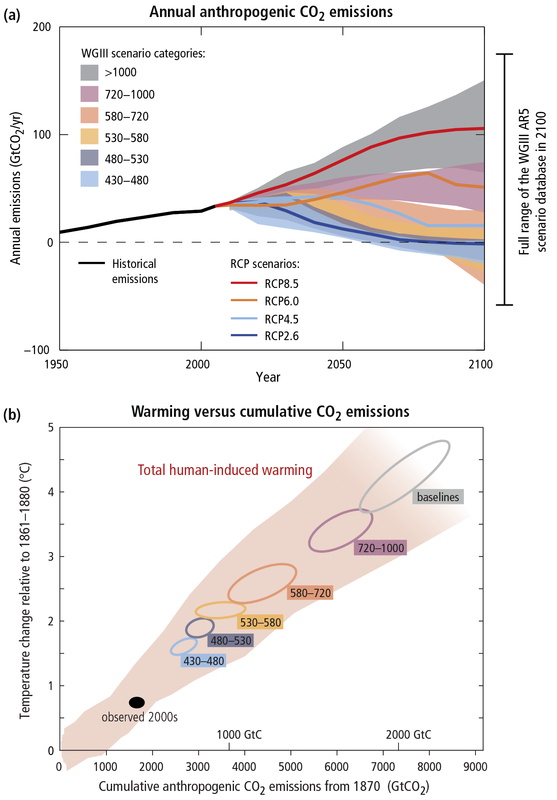

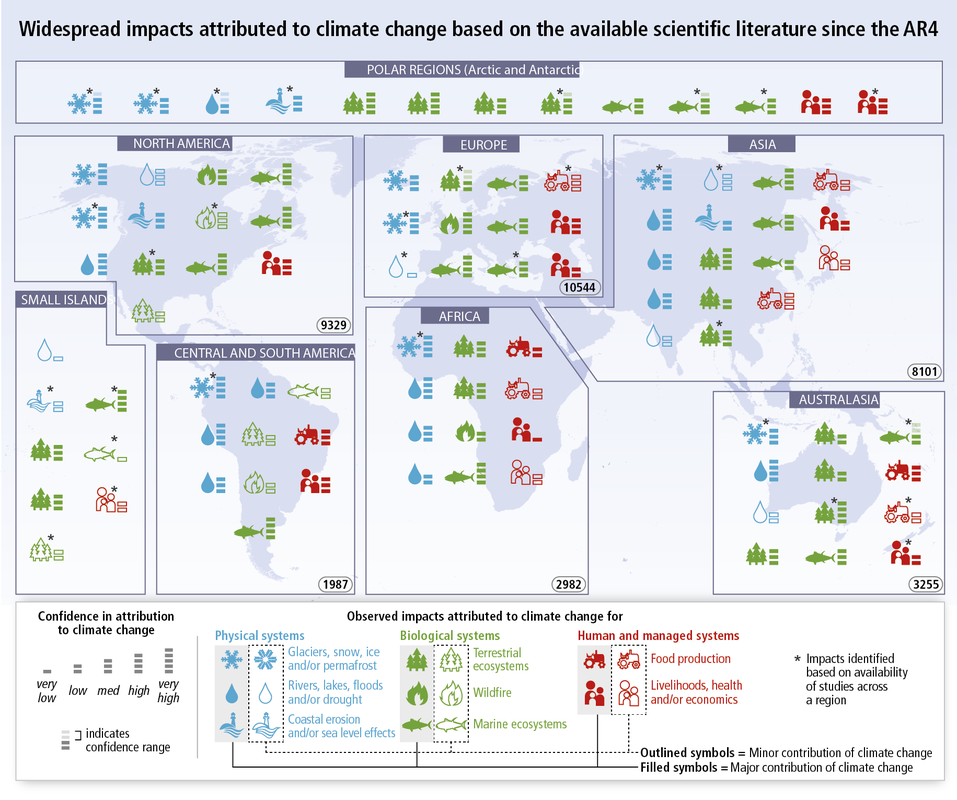

This week, roughly 40,000 delegates from 147 nations gather in Paris for the twenty-first annual "Conference of Parties" (COP21) in the fight against climate change. For the first time, participating governments will seek a legally binding agreement on mitigating and adapting to climate change. Their ambition will be to ensure that average global temperatures do not rise more than two degrees Celsius above their preindustrial averages. However, this goal now faces at least four serious challenges. First, the governments of some developing countries, led by India, have insisted that relatively poor countries should not have to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. They maintain that developed nations long exploited cheap energy to build their present wealth. These countries should therefore pay the price for global warming. Such thinking is not without merit, but it ignores the political challenges faced by governments in developed nations. It is also disingenuous: developing countries now account for such a large share of the world's carbon emissions that no cuts made by wealthy nations alone could sufficiently mitigate climate change. Second, pledges currently made by participating governments would still lead to warming of nearly three degrees Celsius, well beyond the two degree limit suggested by scientists. Third, while that limit is the most ambitious goal we can now hope to achieve, it may not be enough to avoid catastrophic and irreversible changes in regional environments. Studies of past climates - many described on this site - have revealed the disturbing vulnerability of ecosystems and civilizations to even minor fluctuations in average global temperatures. Finally, fourth, a poll recently carried out in twenty countries has revealed sharply declining popular support for ambitious climate change targets at COP21. This disheartening shift in public opinion may reflect new fears about terrorist attacks launched by ISIS, which appears to be the more pressing problem. Yet some recent scientific articles conclude that the Syrian civil war, and in turn the rise of ISIS, may have been partially enabled by climate change. Nevertheless, the urgency of action has never been more clear. This year will be, by far, the warmest ever recorded, and October was an especially hot month even in that context. This is a map of global temperatures in October, relative to worldwide averages between 1951 and 1980: The following graph compares average global temperatures this year with some other years of record-breaking month. It shows what can happen when an extreme El Niño compounds the warming influence of greenhouse gas emissions: Just before the students of my climate history course left for their Thanksgiving holidays, they had to endure one of my gloomier lectures. I gave them a vision of how Earth's climate will change in the coming century. In the United States, the act of giving thanks for what we have is quickly followed by a mad drive to have even more, on "Black Friday" and "Cyber Monday." Yet, the science on climate change shows that, on a societal scale, our drive to consume is devouring our future. After I gave my lecture, it occurred to me that, during COP21, this vision of the coming century should be widely shared by climate change researchers. It may be our best response to the headwinds that now challenge a comprehensive climate agreement. I began my lecture by explaining that, according to model simulations in the latest IPCC Assessment Report, this is how global temperatures and precipitation patterns will likely change by 2081-2100, relative to averages in 1986-2005: That's according to middle-of-the road greenhouse gas emission scenarios (in other words, if we take only moderate action to reduce our carbon emissions). These maps reveal that regional differences in the scale of warming will dramatically increase the overall impact, for human beings, of even modest global increases in average annual temperatures. The Arctic will likely be much warmer and wetter in 2100 than it is today, for example, while Europe will probably be far drier and hotter. The impact of these changes will be further exacerbated by an increase in the regional frequency of weather extremes. Hurricanes, typhoons, and cyclones may well become more severe, if not necessarily more common, and heatwaves will be far more frequent. The following maps demonstrate that, in many places, both droughts and floods will also be much more common in 2080-2099 than they were in 1986-2005. They depict changes according to very high warming scenarios. The warming of the Arctic climate is already transforming the "cryosphere," the part of the Earth where water remains frozen. Melting ice is contributing to sea levels that are already rising because water expands when it gets warmer. These changes will continue in the decades ahead. A recent study concluded that sea levels could rise by nearly seven feet by 2100. That would be enough to swamp many of the world's coastal cities. However, this prediction may be underselling the threat, because it does not account for the catastrophic ice loss in Greenland and Antarctica. Scientists have recently discovered that Greenland is melting more quickly and more thoroughly than they had expected. The complete melting of the Greenland ice sheet will probably take thousands of years, but it will eventually raise sea levels by some 23 feet. The story in Antarctica is far more complex. Scientists recently announced that the West Antarctic Ice Sheet has started an irreversible but relatively slow-moving collapse. This conclusion was not included in the fifth IPCC assessment report, but it will eventually raise global sea levels by a further 12 feet. Nevertheless, a new NASA study has found that an increase in Antarctic snow accumulation that began 10,000 years ago is adding enough ice to the continent to more than outweigh losses from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. Within 20 to 30 years, however, Antarctic ice losses should start exceeding accumulation. Even the IPCC's conservative sea level predictions are concerning. These maps compare sea levels in 1986-2005 to their projected averages in 2081-2100. Atmospheric and oceanic circulation ensure that sea levels are not uniform, and some of the most severe changes will affect the coasts of Africa. This widely shared highlight from the documentary Chasing Ice provides a dramatic example of the changes underway in Greenland: Some of the most troubling manifestations of climate change are unfolding in the world's oceans. Approximately 30 to 40% of human carbon emissions dissolve into water. Some of these emissions react with water to form carbonic acid, which ultimately increases ocean acidity through additional chemical reactions. Oceans will probably become 170% more acidic by 2100. The current rate of acidification is 100 times faster than any other changes in ocean acidity over the last 20 million years. Ocean acidification will have catastrophic consequences for many (but not all) kinds of marine life. It will depresses metabolic rates for animals such as jumbo squid, and dampen immune responses in animals such as blue mussel. By killing algae, it will threaten reef ecosystems by bleaching coral and reducing oxygen levels. The following maps show oceanic pH levels in 1850 (top) and, according to forecasts, 2100 (bottom). The lower the number (and warmer the colour), the higher the pH level (and more acidic the water). All of these forecasts assume that anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions will keep the world's climate below so-called "tipping points" or "threshold values" that could set in motion some truly dramatic, planet-altering changes. However, these tipping points are poorly understood, and our emissions may well exceed them. One of these tipping points would lead to the breakdown of the vast ocean current called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which helps govern the world’s climate. When ice forms in the Arctic and northern Atlantic Oceans, water around it gets saltier and therefore heavier. When it sinks, water from farther south moves north to replace it. This brings heat far into the northern hemisphere. When ice melts on a huge scale, cold freshwater drains into the northern Atlantic and slows down the current. Take a look at the map of October temperatures, at the top of this article. That cold spot near Greenland reflects meltwater from the Greenland ice sheet. The AMOC is already slowing down. Could the collapse of the Greenland ice sheet shut it down completely, and, ironically, bring bitter cold to Europe and North America? More worrisome still is the risk of widespread melting of the permafrost, which currently stores some 1.4 trillion tons of methane. As a greenhouse gas, methane is 84 times more potent than Carbon Dioxide. The permafrost is already starting to melt on a large scale. In 2006, melting Siberian permafrost released 3.8 million tons of methane into atmosphere, but in 2013, that number increased to 17 million tons. There is a feedback loop at work here, because melting permafrost warms the atmosphere, especially in the far north, which then leads to more melting. More dramatic melting of the world's permafrost would lead to more warming than is predicted by even the IPCC's worst-case scenarios. The map below depicts the global distribution of permafrost, and shows the scale of the potential problem: Some the changes I've described will happen, no matter what we do. The complicated graph below depicts the predicted extent of global warming, according to different emissions scenarios. It demonstrates that, even if we dramatically and immediately slash our emissions, the globe will still warm by nearly two degrees Celsius, relative to twentieth-century averages. Yet it also shows that, by acting now, governments can avoid truly catastrophic warming. The world's future is in the hands of the delegates in Paris. In the coming century, even relatively modest global warming may well have devastating consequences for human beings and the species on which we depend. Climate historians have shown that the precise impacts will undoubtedly vary from society to society, and depend much on socioeconomic and technological changes that are, at present, difficult to predict. Predicted advances in biotechnology, artificial intelligence, and energy production, for example, may well transform human vulnerability to climate change. Nevertheless, a warmer world will be a planet less hospitable to human life. The IPCC has published the following map of the ongoing environmental and social consequences of climate change today. If warming temperatures have already had profound global consequences, what will our future have in store? At COP21, international delegates have a chance to take the tough action that will let us avoid a future of climate change catastrophe. However, they will be under enormous pressure to avoid politically damaging agreements now. The warmer future, after all, still feels far off. Yet, in many respects, it is here already. In a year of wildfires, heat waves, catastrophic storms, and drought-fuelled conflict, the need to combat climate change should never feel more urgent.

~Dagomar Degroot |

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed