|

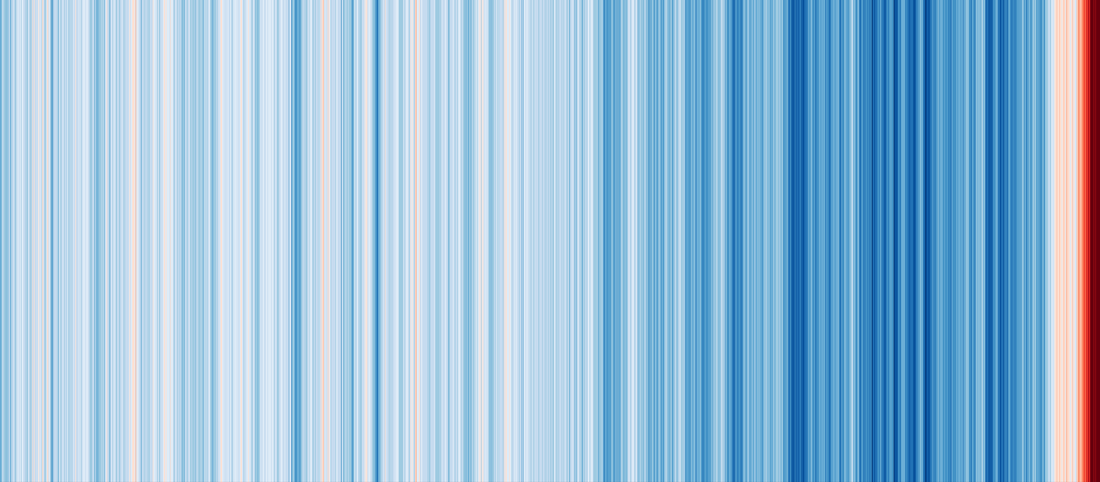

Dr. Dagomar Degroot, Georgetown University Students often ask me: how did climate history – the study of the past impacts of climate change on human affairs – come to be? I usually give the origin story that’s often told in our field: the one that sweeps through the speculation of ancient and early modern philosophers before arriving in the early twentieth century with the emergence of tree ring science and the theories of geographer Ellsworth Huntington. Huntington’s ideas perpetuated a racist “climatic determinism,” I say, but his imprecise evidence for historical climate changes meant that few historians took his claims seriously. Then, in the 1960s and 70s, the likes of Hubert Lamb, Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, and Christian Pfister developed new means of interpreting textual evidence for past climate, and used these methods to advance relatively modest claims for the impact of climate change on history. Their care and precision gave rise to climate history as it exists today – though the field did not attain true respectability until recently, when growing concerns about global warming encouraged many historians to reappraise the past. It’s a compelling story, and true in many respects. Yet it has a problem. Crack open Huntington’s publications, and it’s immediately obvious that there’s an uncomfortable similarity between them and many of the most popular publications in climate history today. Like Huntington, most climate historians write single-authored manuscripts. Like Huntington, many learn the jargon and basic concepts of other fields – such as paleoclimatology – before concluding that this knowledge allows them to identify significant anomalies or trends in past climate. Like Huntington, modern climate historians have assumed that societies were homogenous entities, with some more “vulnerable” to climatic disruption than others. They routinely focus on the rise and fall of societies, typically by focusing on the “fatal synergy” of famines, epidemics, and wars. Such narratives have been influential, and the best of them have helped transform how historians understand the causes of historical change. It is under the scrutiny of climate historians – and many other scholars who consider past environments – that the historical agency or “actancy” of the natural world has gradually come to light. Few historians would now argue that humans created their own history, irrespective of natural forces. Climate historians have also shown that the “archives of nature” – materials in the natural world that register past changes – can be as useful for historical scholarship as the texts, ruins, or oral histories that constitute the “archives of society.” And like other scholars of past climate change, historians have offered fresh perspectives on the challenges of the future: perspectives that may reveal what we should most fear on a rapidly warming Earth. Yet precisely because climate history has become an influential and dynamic field within the historical discipline, it is time to consider how it might be improved. Among other avenues for improvement, it is time to imagine how the field might transcend some of Huntington’s assumptions. It is time to consider how it could be better integrated within the broader scholarship of climate change, and thereby how historical perspectives might genuinely contribute to the creation of policies for the future. And it is time to ask whether the stories climate historians have been telling – those narratives of societal disaster – really represent the most accurate or useful way of understanding the past. I started thinking about that question while working on The Frigid Golden Age, a book that grew out of my doctoral dissertation. When I began my PhD at York University, I assumed my dissertation would confirm that the Dutch Republic, the precursor state to the present-day Netherlands, shared in those fatal synergies that climate historians had linked to the Little Ice Age. After a few months under Richard Hoffmann's tutelage, I learned that a group of scholars had digitized logbooks written by sailors aboard Dutch ships. I realized that those logbooks would allow me to start my research before I could travel to the Netherlands. Working with logbooks encouraged me to look beyond the famines and political disasters that had dominated scholarship on the Little Ice Age. Rather than searching for the climatic causes of disasters, I started thinking about the influence of climate change on daily life (aboard ships). It dawned on me that I could no longer rely on existing reconstructions of temperature or precipitation, which have less relevance for marine histories. I needed to learn more about atmospheric and oceanic circulation, which meant that I had to begin to understand the mechanics by which the climate system actually operates. I had to consider how circulation patterns manifested at small scales in time and place, so I had to think carefully about what it meant when one line of evidence (or “proxy”) – my logbooks, for example – contradicted another. Gradually, I learned to abandon my earlier assumptions, and to reimagine modest climate changes – such as those of the Little Ice Age – as subtle and often counterintuitive influences on human affairs. It didn’t surprise me when, shortly before I finished my PhD, a landmark book in climate history lumped the Dutch in among other examples of societies that shared in the crises of the Little Ice Age. By then I was framing the Republic as an “exception” to these crises, a unique case in which the impact of climate change was more ambiguous than it was elsewhere. Now, I started to wonder: was the Republic really as big of an exception as I had thought? Or were the crises of the Little Ice Age less universally felt than historians had assumed? Had climate historians systematically ignored stories of resilience and adaption? It was a question with significant political implications. By the time I arrived at Georgetown University in 2015, “Doomism” – the idea that humanity will inevitably collapse in the face of climate change – was just beginning to take off. In popular articles and books it relies primarily on two things: a misreading of climate science (occasionally with a heathy dose of skepticism for “experts” and the IPCC), and an accurate reading of climate history as a field. Past societies have crumbled with just a little climate change, Doomists conclude – why will we be any different? At around the time I published The Frigid Golden Age in 2018, I noticed that more of my students were beginning to echo Doomist talking points. I worried, because in my view Doomism is not only scientifically inaccurate, but also disempowering. If collapse is inevitable, why take action? It seemed perverse that the idea would gain momentum precisely as young, diverse climate activists were at last raising the profile of climate change as an urgent political issue. It seemed that now was the time to return to the question that had bothered me as a graduate student. So it was that I applied for a little grant from the Georgetown Environment Initiative (GEI), a university-wide initiative that connects and supports faculty working on environmental issues. I asked the GEI for funds to host workshops that would bring together scholars who had begun to study the resilience of past communities to climate change. Through discussions at those workshops, I hoped to draft an article that would highlight many such examples – and perhaps systematically analyze them to find common strategies for adaptation. The goal would be submission to a major scientific journal: precisely the kind of journal that had helped to popularize the idea that societies had repeatedly collapsed in the face of climate change. I soon realized that the workshops would have to connect scholars in many different disciplines, not just history. A striking series of articles was just then beginning to call for “consilience” in climate history: the creation of truly interdisciplinary teams wherein sources and methods would be shared to unlock new, intensely local histories of climate change. My experiences as the token historian on scientific teams that had developed their projects long before asking me to join had by then caused me to doubt the utility of working on research groups. Yet the new concept of consilience - and conversations with my new colleague Timothy Newfield - convinced me that there was much to be gained if scholars in many disciplines worked together to develop a project from the ground up. Eventually I learned that the GEI would award me enough money to host one big workshop at Georgetown. That was exciting! Arrangements were made, and before long Kevin Anchukaitis, Martin Bauch, Katrin Kleemann, Qing Pei, and Elena Xoplaki joined Georgetown historians Jakob Burnham, Kathryn de Luna, Tim Newfield, and me in Washington, DC. After a fruitful day of discussion, my colleagues suggested a change of focus. Why not consider how climate history as a field could be improved by telling more complex stories about the past? It was a compelling idea, but I added a wrinkle. What if those more complex stories were also often stories about resilience? To me, complexity and resilience could be two sides of the same coin. We decided to focus our work on periods of climatic cooling in the Common Era – the last two millennia – and accordingly I began to refer to our project as “Little Ice Age Lessons.” Then we settled on a basic work plan. I would draft a long critique of most existing scholarship in our field. Meanwhile, our paleoclimatologists would collaborate on a cutting-edge summary of both the controversial Late Antique Little Ice Age, a period of at least regional cooling that began in the sixth century CE, and the better-known Little Ice Age of (arguably) the fourteenth to nineteenth centuries. It had dawned on me while writing The Frigid Golden Age that many climate historians took climate reconstructions at face value, especially badly dated reconstructions, and used them to advance claims that no paleoclimatologist would feel comfortable making. One recent, popular book, for example, claims that the Little Ice Age cooled global temperatures by about two degrees Celsius; that's off by around an order of magnitude. False claims about climate changes lead to erroneous assumptions about the impact of those changes on history, and dangerous narratives about the risks of present-day warming. With our study, we hoped to model how to use - and not use - paleoclimatic reconstructions. I would work with one paleoclimatologist in particular – Kevin Anchukaitis of the University of Arizona – to reappraise a statistical school of climate history that quantifies social changes in order to find correlation, and therefore causation, between climatic and human histories. By applying superposed epoch analysis – a powerful statistical method that can accommodate lag between stimulus and response – to global commodity databases, we hoped to identify correlations that statistically-minded climate historians had missed, or else interrogate correlations that they had already made. Finally, our historians and archaeologists would contribute qualitative case studies that would each reveal how a population had been resilient or adaptive in the face of climate change. I hoped that these case studies would address my criticisms of our field, partly by relying on the cutting-edge reconstructions our paleoclimatologists would provide. While our initial group would have plenty of case studies to share, I immediately reached out to solicit more and more diverse examples of resilience, primarily from those parts of the world that Little Ice Age historians had most frequently linked to disaster. In the coming months, Fred Carnegy, Jianxin Cui, Heli Huhtamaa, Adam Izdebski, George Hambrecht, and Natale Zappia joined our team. Kevin soon became an indispensable partner. As the months went by, we exchanged countless messages on just about every concern I could come up with, most of which initially dealt with how to identify and interpret regional paleoclimatic reconstructions. After I found and began to interpret commodity price databases from across Europe and Asia, we began our statistical analysis. I was surprisingly unsurprised when we uncovered no decadal correlations between temperature or precipitation trends and the price of key staple crops across China, India, the Holy Roman Empire, France, Italy, or the Dutch Republic. In fact, we found no correlations even between annual temperatures and prices. We did find that precipitation anomalies correlated with price increases, but only during a small number of extreme years. These results, I thought, could be really important. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of publications in climate history all assume a relatively direct link between climatic trends, grain yields, and food prices. In fact, many studies conclude that it is from this basic relationship between climate change and the cost of food that all the economic, social, political, and cultural impacts of climate change follow, past or present. Had we found compelling statistical evidence that connections between climatic and human histories were subtler and more complicated in the Common Era than previously assumed? Maybe not. Kevin worried that we were falling into precisely the tendency that we hoped to criticize in our article: the temptation to reach grand conclusions on the basis of flimsy correlations. Heli Huhtamaa, who authored some of the most important scholarship that links climate change to harvest yields, soon explained that our price data did not necessarily reflect changes in yields - and that our price databases were far from comprehensive. Adam Izdebski consulted economic historian Piotr Guzowski, who pointed out that the gradual process of market integration in the early modern centuries may have blunted the impact of harvest failures (we would later stress this integration as a source of resilience). At the same time, I conferred with climate modeler Naresh Neupane, who asked insightful questions about our statistical methods. I also consulted leading climate historian Sam White for his perspective. He argued that in order to reach persuasive conclusions, we needed to develop or adopt a model for the impact of climate change on agriculture. Only then could we understand what our price series and correlations – or lack thereof – were telling us. I had mixed feelings – shouldn’t our impact model flow from our data, rather than the reverse? – yet I asked Georgetown PhD student Emma Moesswilde to join our team by sorting through just about every model ever developed by climate historians. As I suspected she would, Emma concluded that most assumed a relatively direct link between temperature, precipitation, harvest yields, and staple crop prices. Meanwhile, our case studies were beginning to flow in. I had established a hands-on workflow, with a constant pace of reminder emails and shared Google folders and files. I was incredibly fortunate to work with brilliant and motivated colleagues who collectively met our deadlines, despite many other commitments and pressures. By the summer of 2019, I had nearly every case study that would enter our article. Now it was a process of shortening each case study from several pages to about a paragraph each . . . then finding connections between them, organizing them according to those connections, and interrogating them using our cutting-edge climate reconstructions. The weeks dragged by. I hazily remember working long hours late into the night or in the wee hours of the morning, while my newborn son refused to sleep. If integrating our case studies was difficult, I found it surprisingly easy to criticize our field. Climate historians, I argued, had often misused climate reconstructions, and many uncritically followed methods that ended up perpetuating a series of cognitive biases. While climate history was multidisciplinary, it was not yet sufficiently interdisciplinary, meaning that it was still unusual for scholars in a truly diverse range of disciplines to work together. The upshot was that many publications were unconvincing either because they misjudged evidence, ignored causal mechanics, did not attempt to bridge different scales of analysis, or did not pay sufficient attention to uncertainty. By the fall, it was clear to me that something exciting might be taking shape. When Kevin joined us at Georgetown for a few days, he suggested that we might consider submitting to Nature, the world’s most influential journal. I found the idea tremendously exciting, if daunting. While still a young child I’d dreamed of publishing in Nature, inspired perhaps by tales told by a much-older brother who was then pursuing a doctorate in neuroscience. Now I thought of the influence our publication could have if Nature would publish it – and of career-altering ramifications for our graduate student co-authors in particular. I also thought about what it might do not only for the field of climate history (and relatedly, environmental history) but also more broadly for the transdisciplinary reach and prestige of qualitative, social science and humanistic scholarship. When fall turned to winter, I submitted a synopsis of our article to Nature, and early in the next year I was delighted (and frankly surprised) to receive an encouraging response. Our editor, Michael White, suggested that he would be interested in a complete article – but only if we considered including a research framework that would allow climate historians to address our criticisms. It was a crucial intervention. Kevin and I had worried that the part of our article that dealt with reconstructions and criticisms was becoming increasingly distinct from our statistical and qualitative interpretations of history. Yet a framework could allow us to convincingly bridge these halves. Michael asked whether we wished to submit a Nature Review, a format that would give us a bit more space and much more latitude to adopt our own structure. Yet space was still at a premium, and with our article so packed for content we decided that our statistical analysis had to go. This was a painful choice for me. While several co-authors remained skeptical, I considered it to be important, if incomplete, and I wonder whether to pursue its early conclusions in a future publication. Commodity prices do not tell us directly how climate anomalies influenced agriculture, yet to me the lack of statistically significant correlations between those anomalies and prices could still reveal something important about the impact of (modest) climate change on human history. By the spring, COVID-19 had reached all of our institutions, and we all grappled with a depressing new reality. As we transitioned to online teaching and those of us with children struggled with the absence of school or daycare, the pace of work slowed. It slowed, too, because I found the work more challenging than ever before. A key part of our process now involved interrogating our case studies more rigorously than before, and we soon found that many of those studies – including my own – suffered from precisely the problems we were attempting to identify and criticize. At first, this really troubled me. I sent question after annoying question to our co-authors, each of which, I’m sure, required extraordinary effort to answer. Not for the last time was I grateful for selecting such a remarkable team. While some scholars might have been affronted by my questions, all the answers I received were thoughtful and constructive. After a while, it dawned on me that this process of revision and interrogation could be an important part of the new research framework we hoped to advance – and a critical advantage of a consilient approach to climate history. We decided to be entirely upfront about the process, and in turn about how we were able to overcome the shortcomings that are all but inevitable in single-authored scholarship. We hoped that this expression of humility, as we saw it, would encourage other scholars to pursue the same approach. By early summer we had a complete draft. We now collaboratively undertook rounds of painstaking revisions to a Google Doc. As the weeks went by, we sharpened our arguments, excised unnecessary diversions, and crafted case studies that, we thought, convincingly considered causation and uncertainties. Everyone took part, and by the fall we were ready to submit. It was only when we received our peer reviews and Michael’s comments that I began to really believe that we might actually be able to publish in Nature. Still, our reviews did raise some criticisms that we needed to address. Using Lucidchart I created detailed tables, for example, that allowed us to visualize how we had interrogated each of our case studies, and a recent environmental history PhD and cartographer, Geoffrey Wallace, designed a crystal clear map to help readers interpret those tables. One big issue occupied me for nearly a week. A reviewer pointed out that we did not have a detailed definition of resilience, and wondered whether we even needed that term. Indeed “resilience” has become a loaded word in climate scholarship and discourse - and this requires a short digression. In 1973, ecologist Crawford Stanley Holling first imagined resilience as a capacity for ecosystems to “absorb change and disturbance” while maintaining the same essential characteristics. In a matter of years, scholars of natural hazards and climate change impacts appropriated and then modified the concept for their own purposes. Today, it is ubiquitous in the study of present and projected relationships between climate change and human affairs. Yet what it means exactly has not always been clear. Older definitions of the concept in climate-related fields privileged “bouncing back” in the wake of disaster, and were eventually criticized for assuming that all social change should be viewed negatively. Newer definitions can encompass change of such magnitude that all possible human responses to environmental disturbance could be classified as resilient – including collapse. The concept of resilience is also controversial for political reasons. Critics argue that a focus on resilience can carry with it the assumption that disasters are inevitable, and that it therefore normalizes and naturalizes the sources of vulnerability in populations. It can serve neoliberal ends, critics point out, by displacing the responsibility for avoiding disaster from governments to individuals. Since vulnerability is often the creation of unjust political and economic structures, the concept of resilience can obscure and thus support problematic power relations. Critics point out that normative uses of the concept can be used to denounce and “other” supposedly inferior – and typically non-western – ways of coping with disaster. Still, we decided that resilience was a term worth using. Only it and “adaptation” are terms that provide immediately recognizable and therefore accessible means of conceptualizing interactions between human communities and climate change that are different from, and often more complex than, those that can be characterized as disastrous. We decided that recent scholarship had moved beyond using the concept narrowly; in fact the IPCC now incorporates active adaptation within its understanding of resilience. We concluded that if we were careful to precisely define how we were using the term, and if we emphasized how resilience for some had come at the expense of others, then our use of resilience could allow us to more directly communicate to the general public – and to the policymaking community. In revisions it also became clear to us that many scholars who are not historians remain unfamiliar with the term “Climate History,” and associate it narrowly with the historical discipline. What we needed was a new term that, in the wake of our article, would unite scholars in every discipline that considered the social impacts of past climate change – and thereby encourage precisely the kind of consilient collaboration we call for. The term would need to communicate that this field was not another genre of the historical discipline - like environmental history - and it would need to stress our shared focus on the impacts of climate change on society. After we’d bounced around a number of options that seemed to privilege one discipline over another, Adam suggested “History of Climate and Society,” or HCS. We all agreed: this was a term that could work. Our article improved dramatically owing to the constructive suggestions of our editor and reviewers. Soon after we submitted our revisions, we learned to our delight that we’d been accepted for publication. Thanks to Adam, and with the support of press offices at Georgetown and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, we immediately started to plan a major effort to communicate our findings to the press, in at least five different languages. To some extent, this article is part of that effort, and I hope it expresses some of the key findings of an article that, we hope, will also be accessible to the general public. Yet climate historians – or rather, HCS scholars – are the most important audience for this piece. I hope it illuminates, first, what it's actually like to work in consilient teams that aim to publish in major scientific journals. Working in such teams will be foreign to many historians in particular, and it reminded me a great deal of what it's been like to establish, then direct, both this resource and the Climate History Network. It is a managerial task not so different from running a small company or NGO, and it exposed for me how, in interdisciplinary scholarship, the service and research components of academic life easily blend together. Most importantly, I hope this article communicates some of the benefits of working on a thoroughly interdisciplinary, consilient team. On many occasions my co-authors raised a point I wouldn’t have considered, corrected an argument I had intended to make, or warned me against using data that would have led us astray. Through discussions with our brilliant team, I learned far more while developing this project than I have while crafting any single-authored article. Teamwork was not always easy, and it was extraordinarily time consuming. Not all academic departments in every discipline will fully recognize its value. Yet I’m convinced that it is usually the best way to approach HCS projects. And now it gives me a tremendous feeling of satisfaction to know what our team accomplished together. Beyond these questions of process and method, it’s worth asking where HCS studies stand today. Certainly our article did not disprove that climate changes have had disastrous impacts on past societies – let alone that global warming has had, and will have, calamitous consequences for us. Archaeologists moreover have long considered the resilience of past populations, and some of our conclusions will not surprise many of them. Yet we hope that HCS scholars in all disciplines will now pay more attention to the diversity of past responses to climate change, including but no longer limited to those that were catastrophic. We also hope that our article will both discourage Doomist fears and inspire renewed urgency for present-day efforts at climate change adaptation. According to the Fourth National Climate Assessment, in the United States “few [adaptation] measures have been implemented and, those that have, appear to be incremental changes.” The story is similar elsewhere. Our study shows that the societies that survived and thrived amid the climatic pressures of the past were able to adapt to new environmental realities. Yet we also find that adaptation for some social groups could exacerbate the vulnerability of other groups to climate change. Our study therefore provides a wakeup call for policymakers. Not only is it critical for policymakers to quickly implement ambitious adaptation programs, but a key element of adaptation has to be reducing socioeconomic inequality. Adaptation, in other words, has to include efforts at environmental and social justice. That is, perhaps, the most important Little Ice Age lesson of all. Dagomar Degroot, Kevin Anchukaitis, Martin Bauch, Jakob Burnham, Fred Carnegy, Jianxin Cui, Kathryn de Luna, Piotr Guzowski, George Hambrecht, Heli Huhtamaa, Adam Izdebski, Katrin Kleemann, Emma Moesswilde, Naresh Neupane, Timothy Newfield, Qing Pei, Elena Xoplaki, Natale Zappia. “Towards a Rigorous Understanding of Societal Responses to Climate Change.” Nature (March, 2021). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03190-2.

0 Comments

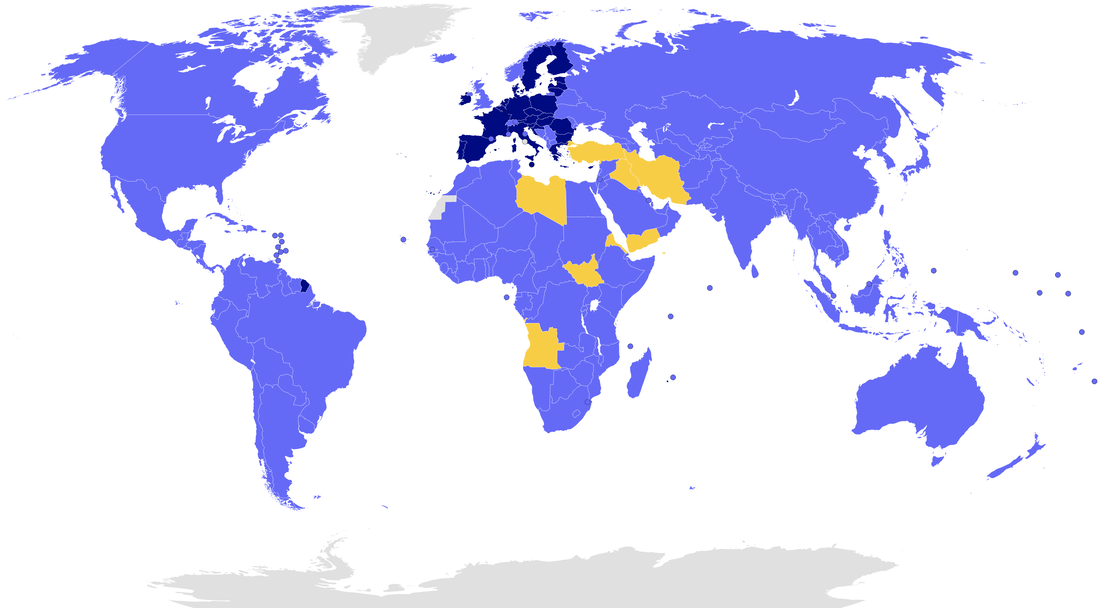

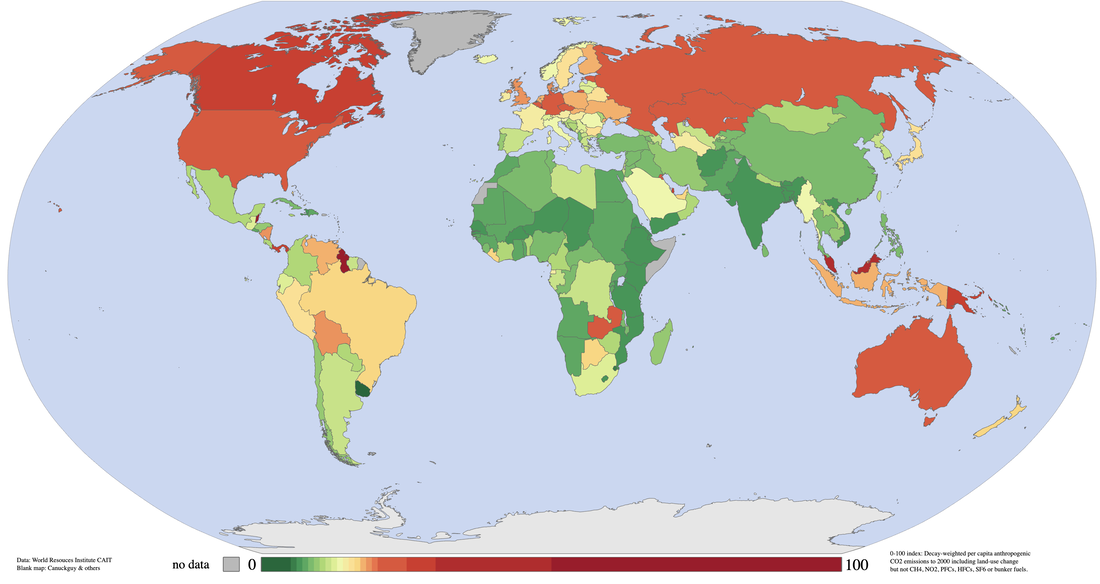

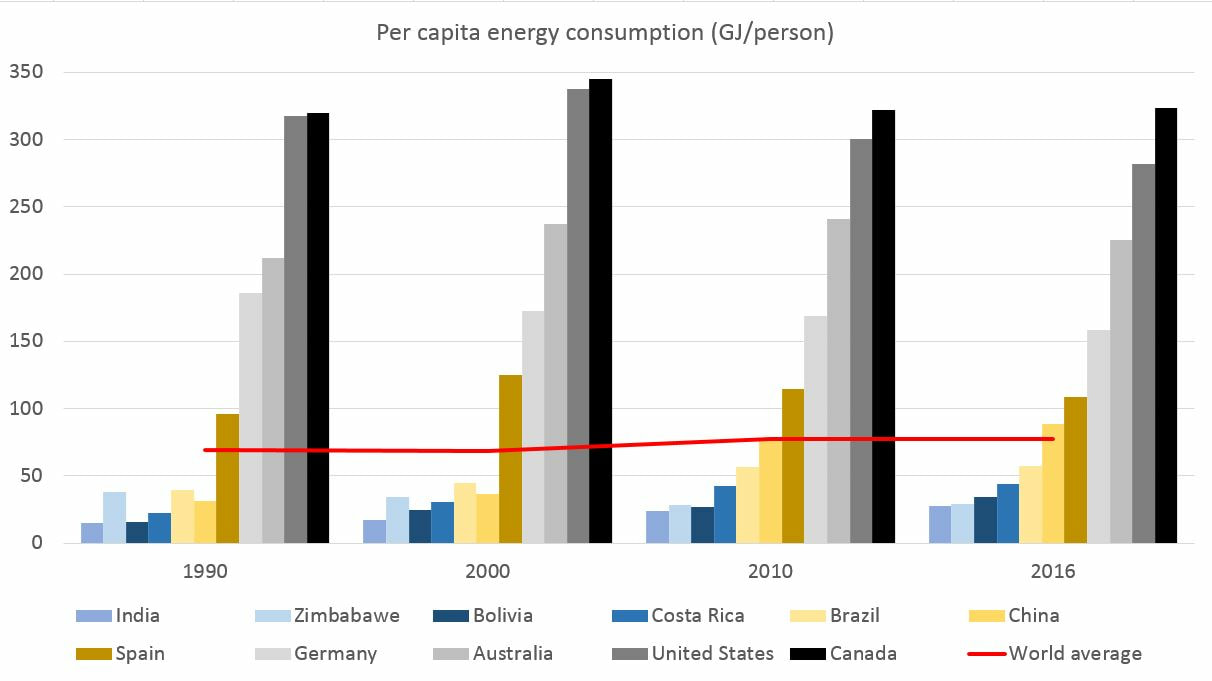

Prof. Lisa Benjamin, Lewis & Clark College of Law As we enter the 2020s, the backdrop of the climate crisis remains grim. Recent scientific reports tell us that global greenhouse gas emissions are increasing, not declining as they need to. Emissions increased by 1.5% in 2017, 2% in 2018 and are anticipated to increase by 0.6% in 2019.[i] While emissions are decreasing too slowly in industrialized countries, they are increasing all too quickly in large developing countries. Despite this increase, per capita emissions in the United States and Europe remain 5-20-fold higher than in China and India,[ii] and a significant number of emissions in developing countries are attributable to the manufacture and production of goods consumed in developed countries. The window to achieve the Paris Agreement’s goals of limiting mean global temperature increases to well below 2°C above pre-industrial averages, and the aspirational goal of a 1.5°C limited increase, is closing quickly. Scientists are increasingly warning of the catastrophic threats of climate change.[iii] Lack of progress by the world’s governments places vulnerable countries such as small island developing states, as well as vulnerable communities within developing and developed countries, at increased risk.[iv] As the United States recently submitted its official notice to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, questions have been raised about the structural integrity of the agreement, and whether it can withstand these countervailing pressures. The Paris Agreement is an internationally legally binding treaty, but its provisions contain sophisticated and varying levels of ‘bindingness’. In terms of emissions reductions, parties have legally binding procedural obligations to submit nationally determined contributions (or NDCs) every five years, but the level of emissions contained within those NDCs are “nationally determined” – i.e. up to each party to individually decide based on their national circumstances. In this sense, the Paris Agreement contains binding obligations of conduct, but not of result. The treaty was intentionally structured with this type of “bottom up”, flexible architecture as a result of the previous history of climate treaties. The UNFCCC, agreed to in 1992, has almost universal participation (including, for now, the United States). As a framework, umbrella treaty it has few specific binding provisions. The ultimate objective of the Treaty (and any related agreements, which would include the Paris Agreement) is to achieve stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations at a level that would avoid dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system.[v] The definition of ‘dangerous interference’ was never fully articulated, and so the global temperature goals in the Paris Agreement of well below 2°C and 1.5°C flesh out this provision. The objectives of the UNFCCC were to be achieved on the basis of equity, in accordance with common but differentiated responsibilities, and the respective capabilities of the parties. Developed country parties were to take the lead in combating climate change.[vi] These principles were based upon the historical responsibility of developed countries for greenhouse gas emissions, and the acknowledgement that developing countries had fewer financial, technological, and human resources to tackle climate change, as well as high levels of poverty. With these principles in mind, in 1997 the Parties to the UNFCCC agreed the Kyoto Protocol in order to provide for more specific, binding emission reduction targets. Only developed country parties took on binding emissions reduction targets, which were housed in Annex I of the Protocol. They became known as ‘Annex I parties’ as a result. The Protocol had automatically applicable consequences for breach of the targets, with a robust compliance mechanism. The United States never ratified the Protocol, and a number of parties such as Japan and Canada either left the Protocol or have not ratified its second commitment period for a number of reasons. As emissions from developing countries rose significantly over the years, and existing parties such as Canada were not on target to reach their Protocol commitments, it was clear that a replacement to the Protocol was needed. The Paris Agreement’s flexible approach to NDCs was considered to be the most politically feasible global solution – it would attract almost universal participation from states (including developing states) and provide for cycles by which parties could increase the ambition of their emissions reductions over time. Nationally determined contributions are submitted every five years. The initial NDCs were submitted in 2015 and the next round of NDCs are due in 2020. In 2015, it was understood that cumulatively these initial NDCs would not be sufficient to achieve the temperature goals of the Paris Agreement, which is why a system of progressive and cyclical submissions was anticipated. Current NDCs submitted by parties have both conditional and non-conditional targets. For example, a number of developing countries made their emission reduction targets in their NDCs conditional upon receiving adequate levels of climate finance and technical and capacity building. Assuming all initial NDCs were fully implemented, Carbon Action Tracker estimated that global temperature increases would lie between 2.7-3.5°C – far beyond what the Paris Agreement aims for. There are a number of provisions in the Paris Agreement that anticipate increased ambition in countries’ activities. Article 4 states that NDCs should represent progress over time, and should represent its highest possible ambition. Parties can also adjust their NDC to enhance their level of ambition. Together, these provisions create a strong normative expectation that parties would violate the spirit of the Paris Agreement if they downgraded the ambition in their NDCs.[vii] But as there are no binding obligations of result in the Paris Agreement (only of conduct), the compliance mechanism in Article 15 has a very narrow mandate – it is designed to be facilitative, transparent, non-punitive, and non-adversarial. The mechanism does not focus on individual country results unless significant and persistent inconsistencies of information are found, and then only with the consent of the party concerned.[viii] The mechanism does have a systemic review function, and provides for consequences such as engaging in a dialogue with parties, providing them with assistance or recommending an action plan. There are other procedural provisions in the Paris Agreement to keep parties on track, such as an enhanced transparency mechanism to ensure that parties’ processes and targets are transparent.[ix] The transparency provisions are closely associated with the NDCs. For example, under the transparency provisions each party must identify indicators it has selected to track progress towards the implementation and achievement of its NDC.[x] A Global Stocktake also takes place every five years, interspersed between the NDC cycles. The first Global Stocktake will take place in 2023, and will assess the 2020 NDC cycle. The 2028 Global Stocktake will assess the 2025 NDC cycle, and so on. The 24th COP in Katowice provided more detailed rules on what the Global Stocktake will look like. In the future, it will be a combination of a series of synthesis reports, and a number of high-level technical dialogues examining the output of these reports. The second round of NDCs are due in 2020, but countries are already falling behind their existing NDC targets. The activities of some countries, such as Russia, Saudi Arabia and the United States, are ‘critically insufficient’, meaning they would lead to a 4°C+ world.[xi] Activities of the UK, EU, Canada, China and Australia are ‘insufficient’, leading to a 3°C+ world. A few parties such as Costa Rica, India, Ethiopia and The Philippines are on track, with 2°C compatible emissions trajectories. Due to increasing global emissions, emissions reductions will have to be steep in order to stay within the Paris Agreement’s global temperature goals. It is anticipated that emissions reductions of approximately 8% per year are required by every country until the end of the century. According to the withdrawal provisions of the Paris Agreement, the withdrawal of the United States will take effect on 4th November 2020, one day after the US Presidential elections. Should the government change, the United States could re-enter the Paris Agreement easily and relatively quickly. If it does not, the lack of global leadership on climate change by the US could become a drag on other parties’ climate actions and ambitions in the next decade. The 2020s will be a testing time for the Paris Agreement, and as Noah Sachs states, may lead to the Agreement’s breakdown (parties fall short of their commitments) or worse, its breakup as parties withdraw and the agreement collapsing.[1] The Paris Agreement was designed as a flexible yet durable global agreement for the coming decades, so it has no specified end date. It allows for and incentivizes increased ambition by its parties, yet does not legally require ambition as there was no political will at the time for such an agreement. The provisions of the Paris Agreement remain relevant, but always relied on domestic political will to be effective. As climate protests around the world gain pace, and extreme weather events continue to escalate in frequency and severity in the developed and developing world, the significant question remains whether that political will be forthcoming in a sufficient and timely enough fashion to avoid catastrophic climate change. Lisa Benjamin is an Assistant Professor at Lewis & Clark College of Law and a member of the UNFCCC Compliance Committee (Facilitative Branch). Her views do not necessarily reflect those of the UNFCCC Compliance Committee. [1] Noah Sachs, “The Paris Agreement in the 2020s: Breakdown or Breakup?” forthcoming, Environmental Law Quarterly 46(1) (2019).

[i] RB Jackson et al., “Persistent fossil fuel growth threatens the Paris Agreement and Planetary Health,” Environmental Research Letters , Vol 14(12) (2019): 1-7. [ii] Ibid. [iii] William J. Ripple et al., “World Scientists Warning of a Climate Emergency” BioScience, (2019): 1-5. [iv] Lisa Benjamin, Sara Seck and Meinhard Doelle, “Climate Change, Poverty and Human Rights: An Emergency Without Precedent” The Conversation (4th September 2019) https://theconversation.com/climate-change-poverty-and-human-rights-an-emergency-without-precedent-120396. [v] Article 2, UNFCCC, UNTS 1771. [vi] Ibid, Article 3(1). [vii] Lavanya Rajamani and Jutta Brunnée, “The Legality of Downgrading Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement: Lessons from the US Disengagement” Journal of Environmental Law Vol 29 (2017): 537-551. [viii] FCCC/PA/CMA/2018/3/Add.2, Decision 20/CMA.1, paras 2 and 22(b). [ix] Paris Agreement, Article 13. [x] FCCC/CP/2018/L.23 para 65. [xi] See Carbon Action Tracker at https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/. Prof. María Cristina García, Cornell University. People displaced by extreme weather events and slower-developing environmental disasters are often called “climate refugees,” a term popularized by journalists and humanitarian advocates over the past decade. The term “refugee,” however, has a very precise meaning in US and international law and that definition limits those who can be admitted as refugees and asylees. Calling someone a “refugee” does not mean that they will be legally recognized as such and offered humanitarian protection. The principal instruments of international refugee law are the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, which defined a refugee as: "any person who owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it." [i] This definition, on which current U.S. law is based, does not include any reference to the “environment,” “climate,” or “natural disaster,” that might allow consideration of those displaced by extreme weather events and/or climate change. In some regions of the world, other legal instruments have supplemented the U.N. Refugee Convention and Protocol, and these instruments offer more expansive definitions of refugee status that might offer protections to the environmentally displaced. The Organization of African Unity’s “Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa (1969)” includes not only external aggression, occupation, and foreign domination as the motivating factors for seeking refuge, but also “events seriously disturbing the public order.”[ii] In the Americas, the non-binding Cartagena Declaration on Refugees (1984), crafted in response to the wars in Central America, set regional standards for providing assistance not just for those displaced by civil and political unrest but also those fleeing “circumstances which have seriously disturbed the public order.”[iii] The Organization of American States has also passed a series of resolutions offering member states additional guidance on how to respond to refugees, asylum seekers, stateless persons, and others in need of temporary or permanent protection. In Europe, the European Union Council Directive (2004) has identified the minimum standards for the qualification and status of refugees or those who might need “subsidiary protection.”[iv] Together, these regional and international conventions, protocols, and guidelines acknowledge that people are displaced for a wide range of reasons and that they deserve respect and compassion and, at the bare minimum, temporary accommodation. Climate change has been absent in these discussions perhaps because environmental disruptions such as hurricanes, earthquakes, and drought were long assumed to be part of the “natural” order of life, unlike war and civil unrest, which are considered extraordinary, man-made, and thus avoidable. The expanding awareness that societies are accelerating climate change to life-threatening levels requires that countries reevaluate the populations they prioritize for assistance, and adjust their immigration, refugee, and asylum policies accordingly. Under current U.S. immigration law, those displaced by sudden-onset disasters and environmental degradation do not qualify for refugee status or asylum unless they are able to demonstrate that they have also been persecuted on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. This wasn’t always the case: indeed, U.S. refugee policy once recognized that those displaced by “natural calamity” were vulnerable and deserved protection. The 1953 Refugee Relief Act, for example, defined a refugee as “any person in a country or area which is neither Communist nor Communist-dominated, who because of persecution, fear of persecution, natural calamity or military operations is out of his usual place of abode and unable to return thereto… and who is in urgent need of assistance for the essentials of life or for transportation.”[v] The 1965 Immigration Act (Hart-Celler Act) established a visa category for refugees that included persons “uprooted by catastrophic natural calamity as defined by the President who are unable to return to their usual place of abode.” [vi] Between 1965 and 1980, no refugees were admitted to the United States under the “catastrophic natural calamity” provision but that did not stop legislators from opposing its inclusion in the refugee definition. Some legislators argued that it was inappropriate to offer permanent resettlement to people who were only temporarily displaced; while others took issue on the grounds that it undermined the economic recovery of hard-hit countries by draining them of their most highly-skilled citizens. The 1980 Refugee Act subsequently eliminated any reference to natural calamity or disaster, in line with the United Nation’s definition of refugee status. In recent decades, scholars, advocates, and policymakers have called for a reevaluation of the refugee definition in order to grant temporary or permanent protection to a wider range of vulnerable populations, including those displaced by environmental conditions. At present, U.S. immigration law offers very few avenues for entry for the so-called “climate refugees”: options are limited to Temporary Protected Status (TPS), Delayed Enforced Departure (DED), and Humanitarian Parole. The 1990 Immigration Act provided the statutory provision for TPS: according to the law, those unable to return to their countries of origin because of an ongoing armed conflict, environmental disaster, or “extraordinary and temporary conditions” can, under some conditions, remain and work in the United States until the Attorney General (after 2003, the Secretary of Homeland Security) determines that it is safe to return home. [vii] There is one catch: in order to qualify for TPS one already has to be physically present in the United States—as a tourist, student, business executive, contract worker or even as an unauthorized worker. TPS is granted on a 6, 12, or 18-month basis, renewed by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) if the qualifying conditions persists. TPS recipients do not qualify for state or federal welfare assistance but they are allowed to live and work in the United States until federal authorities determine that it’s safe to return. In the meantime, they can send much-needed remittances to their families and communities back home to assist in their recovery. TPS is one way, albeit imperfect, that United States exercises its humanitarian obligations to those displaced by environmental disasters and climate change. It is based on the understanding that countries in crisis require time to recover; if nationals living abroad return in large numbers, in a short period of time, they can have a destabilizing effect that disrupts that recovery. Countries affected by disaster must meet certain conditions in order to qualify: first, the Secretary of Homeland Security must determine that there has been a substantial disruption in living conditions as a result of a natural or environmental disaster, making it impossible for a government to accommodate the return of its nationals; and second, the country affected by environmental disaster must officially petition for its nationals to receive TPS status (a requirement that is not imposed on countries affected by political violence). However, environmental disaster does not automatically guarantee that a country’s nationals will receive temporary protection. The U.S. federal government has total discretion and the decision-making process is not immune to domestic politics. Deferred Enforced Departure (DED) is another status available to those unable to return to hard-hit areas: DED offers a stay of removal as well as employment authorization, but the status is most often used when TPS has expired. In such circumstances, the president has the discretionary (but rarely used) authority to allow nationals to remain in the United States in the interest of humanitarian or foreign policy, or until Congress can pass a law that offers a permanent accommodation. [viii] Humanitarian “parole” is yet another recourse for the environmentally displaced. The 1952 McCarran Walter Act granted the attorney general discretionary authority to grant temporary entry to individuals, on a case-by-case basis, if deemed in the national interest. Since 2002, humanitarian parole requests have been handled by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), and are granted much more sparingly than during the Cold War. USCIS generally grants parole only for one year (renewable on a case-by-case basis). [ix] Parole does not place an individual on a path to permanent residency or citizenship, nor does it make applicants eligible for welfare benefits; only occasionally are “parolees” granted the right to work, allowing them to earn a livelihood and send remittances to communities hard hit by political and environmental disruptions. TPS, DED, and humanitarian parole are only temporary accommodations for select and small groups of people. They are an inadequate response to the humanitarian crisis that will develop in the decades to come. Scientists forecast that in an era of unmitigated and accelerated climate change, sudden-onset disasters will become fiercer, exacerbating poverty, inequality, and weak governance, and forcing many more people to seek safe haven elsewhere—perhaps in the hundreds of millions over the next half-century. In the current political climate, it’s hard to imagine that wealthier nations like the United States will open their doors to even a tiny fraction of these displaced peoples; however, the more economically developed countries must do more to honor their international commitments to provide refuge, especially to those in developing areas who are suffering from environmental conditions they did not create. In the decades to come, as legislators try to mitigate the effects of climate change and help their populations become resilient, they must also share the burden of a human displacement caused by the failure to act quickly enough. María Cristina García, an Andrew Carnegie Fellow, is the Howard A. Newman Professor of American Studies in the Department of History at Cornell University. She is the author of several books on immigration, refugee, and asylum policy. She is currently completing a book on the environmental roots of refugee migrations in the Americas. [i] United Nations, “Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees,” 14, http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/3b66c2aa10. The 1951 Convention limited the focus of assistance to European refugees in the aftermath of the Second World War. The 1967 Protocol removed these temporal and geographic restrictions. The United States did not sign the 1951 Convention but it did sign the 1967 Protocol.

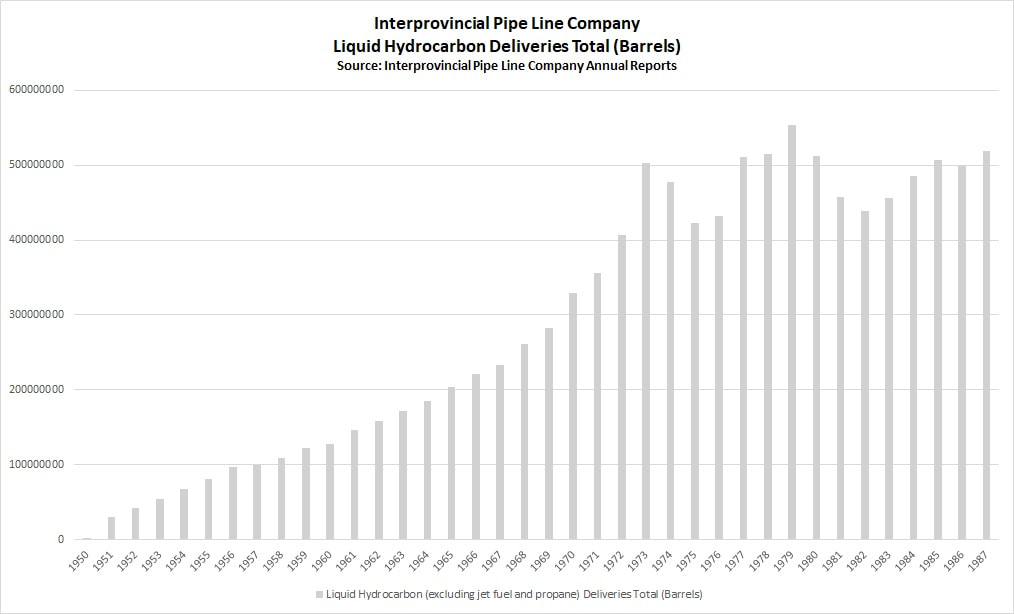

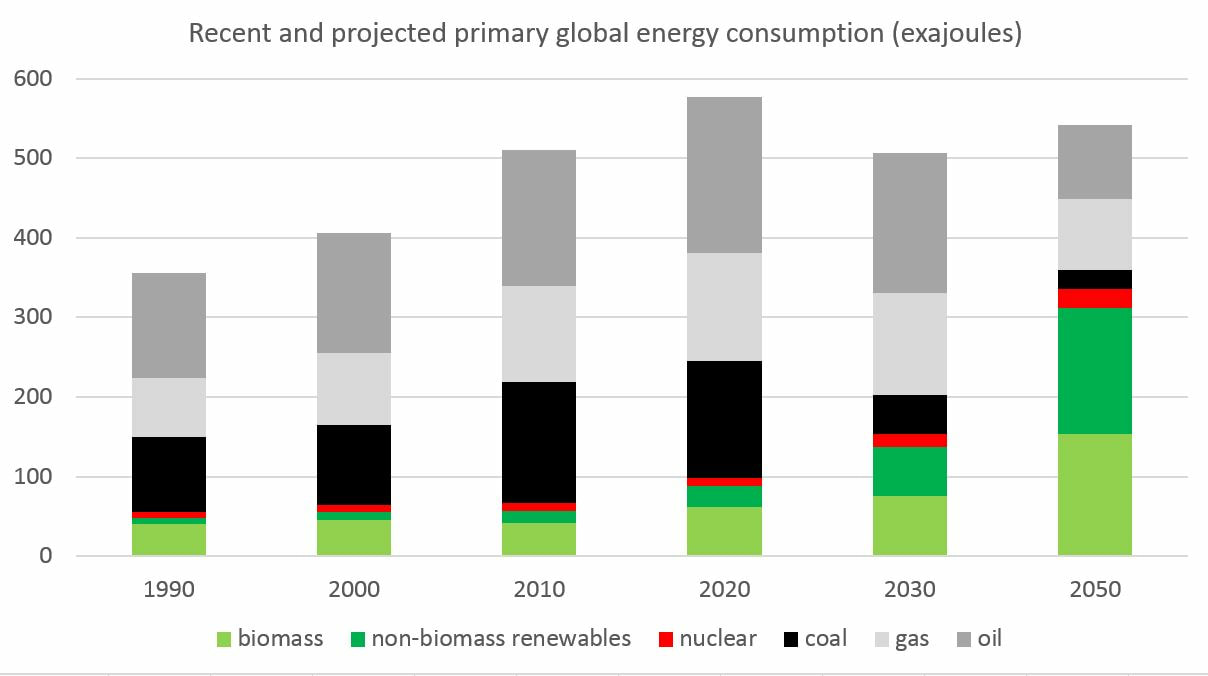

[ii] The OAU convention stated that the term refugee should also apply to “every person who, owing to external aggression, occupation, foreign domination or events seriously disturbing the public order in either part or the whole of his country or origin or nationality, is compelled to leave his place of habitual residence in order to seek refuge in another place outside his country of origin or nationality.” Organization of African Unity, Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa,” http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/about-us/background/45dc1a682/oau-convention-governing-specific-aspects-refugee-problems-africa-adopted.html accessed September 15, 2017. [iii] The Cartagena Declaration stated that “in addition to containing elements of the 1951 Convention…[the definition] includes among refugees, persons who have fled their country because their lives, safety or freedom have been threatened by generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violations of human rights or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed the public order.” Cartagena Declaration on Refugees,” http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/about-us/background/45dc19084/cartagena-declaration-refugees-adopted-colloquium-international-protection.html [iv] European Union, “Council Directive 2004/83/EC,” April 29, 2004, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32004L0083 accessed March 20, 2018. [v] Refugee Relief Act of 1953 (P.L. 83-203), https://www.law.cornell.edu/topn/refugee_relief_act_of_1953. [vi] Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (P.L. 89-236), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-79/pdf/STATUTE-79-Pg911.pdf [vii] Immigration Act of 1990 (P.L.101-649), https://www.congress.gov/bill/101st-congress/senate-bill/358 [viii] USCIS, “Deferred Enforced Departure,” https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/temporary-protected-status/deferred-enforced-departure. [ix] The humanitarian parole authority was first recognized in the 1952 Immigration Act (more popularly known as the McCarran Walter Act). See http://library.uwb.edu/Static/USimmigration/1952_immigration_and_nationality_act.html. See also “§ Sec. 212.5 Parole of aliens into the United States,” https://www.uscis.gov/ilink/docView/SLB/HTML/SLB/0-0-0-1/0-0-0-11261/0-0-0-15905/0-0-0-16404.html Prof. Sean Kheraj, York University. This is the fifth post in a collaborative series titled “Environmental Historians Debate: Can Nuclear Power Solve Climate Change?” hosted by the Network in Canadian History & Environment, the Climate History Network, and ActiveHistory.ca. If nuclear power is to be used as a stop-gap or transitional technology for the de-carbonization of industrial economies, what comes next? Energy history could offer new ways of imagining different energy futures. Current scholarship, unfortunately, mostly offers linear narratives of growth toward the development of high-energy economies, leaving little room to imagine low-energy futures. As a result, energy historians have rarely presented plausible ideas for low-energy futures and instead dwell on apocalyptic visions of poverty and the loss of precious, ill-defined “standards of living.” The fossil fuel-based energy systems that wealthy, industrialized nation states developed in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries now threaten the habitability of the Earth for all people. Global warming lies at the heart of the debate over future energy transitions. While Nancy Langston makes a strong case for thinking about the use of nuclear power as a tool for addressing the immediate emergency of carbon pollution of the atmosphere, her arguments left me wondering what energy futures will look like after de-carbonization. Will industrialized economies continue with unconstrained growth in energy consumption, expand reliance on nuclear power, and press forward with new technological innovations to consume even more energy (Thorium reactors? Fusion reactors? Dilithium crystals?)? Or will profligate energy consumers finally lift their heads up from an empty trough and start to think about ways of living with less energy? Unfortunately, energy history has not been helpful in imagining low-energy possibilities. For the past couple of years, I’ve been getting familiar with the field of energy history and, for the most part, it has been the story of more. [1] Energy history is a related field to environmental history, but also incorporates economic history, the history of capitalism, social history, cultural history and gender history (and probably more than that). My particular interest is in the history of hydrocarbons, but I’ve tried to take a wide view of the field and consider scholarship that examines energy history in deeper historical contexts. There are several scholars who have written such books that consider the history of human energy use in deep time. For example, in 1982, Rolf Peter Sieferle started his long view of energy history in The Subterranean Forest: Energy Systems and the Industrial Revolution by considering Paleolithic societies. Alfred Crosby’s Children of the Sun: A History of Humanity’s Unappeasable Appetite for Energy (2006) begins its survey of human energy history with the advent of anthropogenic fire and its use in cooking. Vaclav Smil goes back to so-called “pre-history” at the start of Energy and Civilization: A History (2017) to consider the origins of crop cultivation. In each of these surveys energy historians track the general trend of growing energy use. While they show some dips in consumption and global regional variation, the story they tell is precisely as Crosby puts it in his subtitle, a tale of humanity’s unappeasable appetite for greater and greater quantities of energy. The narrative of energy history in the scholarship is remarkably linear, verging on Malthusian. According to Smil: “Civilization’s advances can be seen as a quest for higher energy use required to produce increased food harvests, to mobilize a greater output and variety of materials, to produce more, and more diverse, goods, to enable higher mobility, and to create access to a virtually unlimited amount of information. These accomplishments have resulted in larger populations organized with greater social complexity into nation-states and supranational collectives, and enjoying a higher quality of life.” [2] Indeed, from a statistical point of view, it’s difficult not to reach the conclusion that humans have proceeded inexorably from one technological innovation to another, finding more ways of wrenching power from the Sun and Earth. The only interruptions along humanity’s path to high-energy civilization were war, famine, economic crisis, and environmental collapse. Canada’s relatively short energy history appears to tell a similar story. As Richard W. Unger wrote in The Otter~la loutre recently, “Canadians are among the greatest consumers of energy per person in the world.” And the history of energy consumption in Canada since Confederation shows steady growth and sudden acceleration with the advent of mass hydrocarbon consumption between the 1950s and 1970s. Steve Penfold’s analysis of Canadian liquid petroleum use focuses on this period of extraordinary, nearly uninterrupted growth in energy consumption. Only in 1979 did Canadian petroleum consumption momentarily dip in response to an economic recession. “What could have been an energy reckoning…” Penfold writes, “ultimately confirmed the long history of rising demand.” [2] I’ve seen much of what Penfold finds in my own research on the history of oil pipeline development in Canada. Take, for instance, the Interprovincial pipeline system, Canada’s largest oil delivery system. For much of Canada’s “Great Acceleration” the history of more couldn’t be clearer: This view of energy history as the history of more informs some of the conclusions (and predictions) of energy historians. Crosby is, perhaps, the most optimistic about the potential of technological innovation to resolve what he describes as humanity’s unsustainable use of fossil fuels. In Crosby’s view, “the nuclear reactor waits at our elbow like a superb butler.” [4] For the most part, he is dismissive of energy conservation or radical reductions in energy consumption as alternatives to modern energy systems, which he admits are “new, abnormal, and unsustainable.” [5] Instead, he foresees yet another technological revolution as the pathway forward, carrying on with humanity’s seemingly endless growth in energy use. Energy historians, much like historians of the Anthropocene, have a habit of generalizing humanity in their analysis of environmental change. As I wrote last year in The Otter~la loutre, “To understand the history of Canada’s Anthropocene, we must be able to explain who exactly constitutes the “anthropos.”” Energy historians might consider doing the same. The history of human energy use appears to be a story of more when human energy use is considered in an undifferentiated manner. The pace of energy consumption in Canada, for instance, might look different when considering the rich and the poor, settlers and Indigenous people, rural Canadians and urban Canadians. Globally, energy histories around the world tell different stories beyond the history of more including histories of low-energy societies and histories of energy decline. Most global energy histories focus on industrialized societies and say little about developing nations and the persistence of low-energy, subsistence economies. If Smil is correct and “Indeed, higher energy use by itself does not guarantee anything except greater environmental burdens,” then future decisions about energy use should probably consider lower energy options. [6] Transitioning away from burning fossil fuels by using nuclear power may alleviate the immediate existential crisis of global warming, but confronting the environmental implications of high-energy societies may be the bigger challenge. To address that challenge, we may need to look back at histories of less. Sean Kheraj is the director of the Network in Canadian History and Environment. He’s an associate professor in the Department of History at York University. His research and teaching focuses on environmental and Canadian history. He is also the host and producer of Nature’s Past, NiCHE’s audio podcast series and he blogs at http://seankheraj.com. [1] I’m borrowing from Steve Penfold’s pointed summary of the history of gasoline consumption in Canada: “Indeed, at one level of approximation, you could reduce the entire his-tory of Canadian gasoline to a single keyword: more.” See Steve Penfold, “Petroleum Liquids” in Powering Up Canada: A History of Power, Fuel, and Energy from 1600 ed. R. W. Sandwell (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016), 277.