|

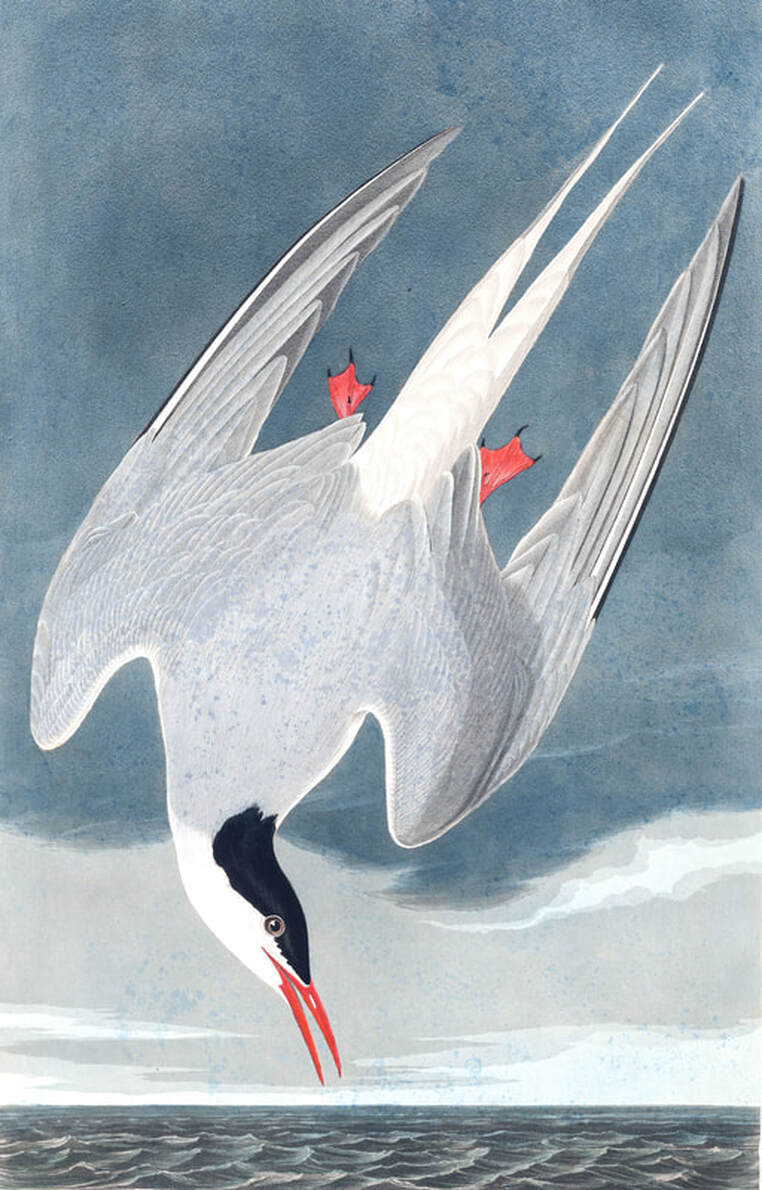

Prof. Anya Zilberstein, Concordia University. On May 11, birders in 130 countries took part in World Migratory Bird Day (WMBD). This citizen science and conservation project enrolls professional and amateur ornithologists twice a year—in May and October—to record sightings of hundreds of species during their spring and fall passages through continental and hemispheric regions, or so-called flyways, across Africa, Europe, Asia, the Americas, and Australasia. WMBD was first organized in 2006 only in part as a way to recruit people to collect more data points. Its purpose is also to convey the urgency of the climate crisis for migratory animals by publicizing how profoundly avian populations, the geography of their flyways, and the timing of their movements have been affected by a host of modern ecological pressures resulting from human activity, including climate change. (Every year WMBD focuses on a different threat, which, for the second annual event in 2007, was “Migratory Birds in a Changing Climate.”) [1] What’s sometimes lost in such initiatives, however, is their considerable history. As I’m discovering in one of my current research projects called “Flight Paths for Birds and other Migrants,” which focuses on theories of migration developed in the 17th and 18th centuries, many of the questions that inform activities like WMBD—even questions about anthropogenic forces—emerged much, much earlier than is usually acknowledged. Participants in WMBD continue a very long line of bird observers who have generated crowd-sourced data to learn more about the behavior of migratory species. Collectively, this constitutes a global, however uneven, record of avian, insect, and other animal movements amassed over centuries. The ancient reliance on birds for a variety of cultural, spiritual, and utilitarian purposes all over the world, informed indigenous knowledge about where and when some itinerant species would normally arrive in a particular place. The earliest avowedly scientific attempts to grasp the geographical and temporal scale of these cyclical movements—including the possible effect of weather and climate on them—date to at least the late 17th century, when individuals increasingly began to keep records of arrival and departure dates. Most historians of ornithology as an empirical science focus on the Victorian period after the development of evolutionary biology, but pre-Darwinian ideas about avian migration recognized, albeit implicitly and without the statistical precision, that 60% of species are migratory (and that many or most other birds may have been migratory millennia ago). Early naturalists, from Cotton Mather to Gilbert White and John James Audubon, were fascinated by what they called ‘birds of passage,’ especially the capacity to dwell in a range of aquatic, aerial, and terrestrial environments and to regularly relocate between different hemispheres in groups. And their attention to these peculiar traits also spurred them to speculate about migratory birds’ susceptibility to change, including changes in their seasonal habitats caused by human societies, such as colonization, the expansion of farmland, and the growth of towns. Their early documents could provide both temporal depth and unique insights into the natural history of climate and migration, particularly for conservationists interested in adaptations to environmental changes in the 20th and 21st centuries. This is especially so because many aspects of migratory patterns—their origins, geography, seasonality, and changes over time—have remained mysterious to scientists, even now. When the biologist Frederick Lincoln coined the term flyway in 1935, he meant it to describe migratory birds’ “ancestral routes”—what were then thought to be the typical extent of the vast ranges and diverse environments they inhabited during different times of the year. Specifying the geography of these migratory corridors would, in turn, assist in ambitious banding projects and the creation of wildlife refuges. [2] Since then, increasingly sophisticated surveillance technologies have been developed to understand how much the boundaries of flyways and periodicity of biannual movements may have actually shifted over time, both in the deep evolutionary past as well as in the present. Yet if it’s clear that rising temperatures, coastal erosion, light and air pollution, urbanization, deforestation, and predation affect migratory bird populations, like much else about our knowledge of their biology, it remains unclear exactly how or how permanently ongoing climate change might shift particular species’ range boundaries, breeding or feeding grounds, and arrival or departure dates. To take just one of numerous examples, in 2010 ecologists in the Netherlands relying on 20 years of trend data gathered by “many thousands of volunteer birdwatchers across Europe” found strong evidence predicting that the continuation of earlier spring thaws and a longer season of heat waves on the continent will likely make climate change an underlying cause of population decline among long-distance migrants like pied flycatchers. Yet five years later, another study with similar parameters and common co-authors concluded that such predictions were less reliable than they’d hoped. “Contrary to expectations,” the patterns they observed between 2004 and 2014 were inconsistent with those from the 1984-2004, leading to equivocal results. [3] It’s not only that as research proceeds some findings about the relationship between climate change and avian migration appear contradictory; it is also that, especially as the current climate crisis grows, the dynamic differs significantly by species, region, and time frame. The history of ornithology can’t help to absolutely resolve these variances: the science of animal migration—like all scientific knowledge—will necessarily be susceptible to revision. But studying historical sources could encourage conservationists to recognize that anthropogenic climate change is only the most recent, if perhaps the most drastic, example of how the lives of non-human animals have long been observed and shaped, for better or worse, by people. Anya Zilberstein is associate professor of history at Concordia University. She is the author of A Temperate Empire: Making Climate Change in Early America (Oxford University Press, 2016), and she is currently working on a new project, "Fodder for Empire: Feeding People Like Other Animals," which examines the history of experiments in producing and distributing non-perishable, high-calorie, low-cost food for animals and people in the British Empire. Special thanks to Jesse Coady for research assistance. [1] <http://www.worldmigratorybirdday.org/about/wmbd-themes-since-2006 >

[2] Frederick C. Lincoln, The Waterfowl Flyways of North America (Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, 1935), 3. [3] Christiaan Both, Sandra Bouwhuis, C. M. Lessells, and Marcel E. Visser, “Climate change and population declines in a long-distance migratory bird,” Nature 441, no. 7089 (2006): 81; Christiaan Both, Chris AM Van Turnhout, Rob G. Bijlsma, Henk Siepel, Arco J. Van Strien, and Ruud PB Foppen, “Avian population consequences of climate change are most severe for long-distance migrants in seasonal habitats,” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 277, no. 1685 (2010): 1259-1266; Marcel E. Visser, Phillip Gienapp, Arild Husby, Michael Morrisey, Iván de la Hera, Francisco Pulido, Christiaan Both, “Effects of Spring Temperatures on the Strength of Selection on Timing of Reproduction in a Long-Distance Migratory Bird,” PLOS Biology 13, no. 4 (2015), e1002120; https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002120. |

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed