|

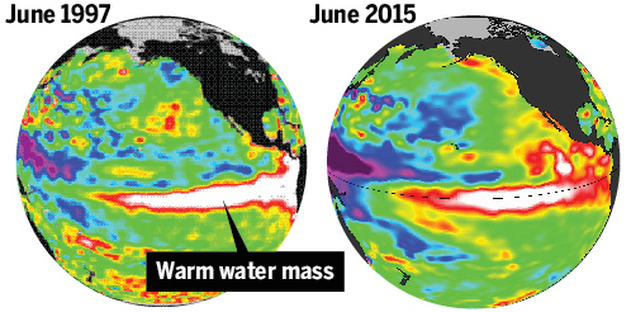

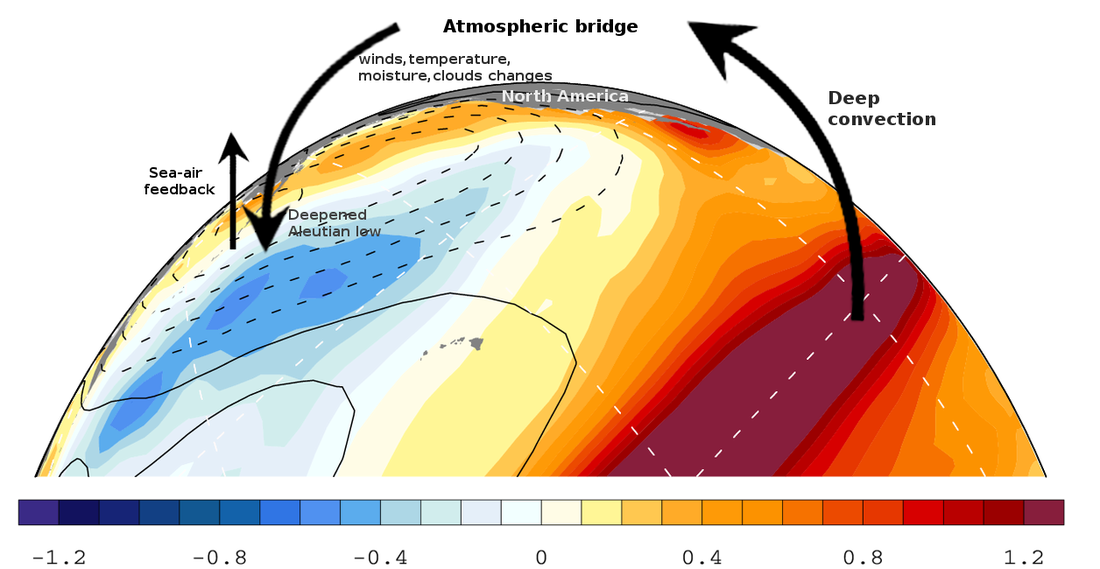

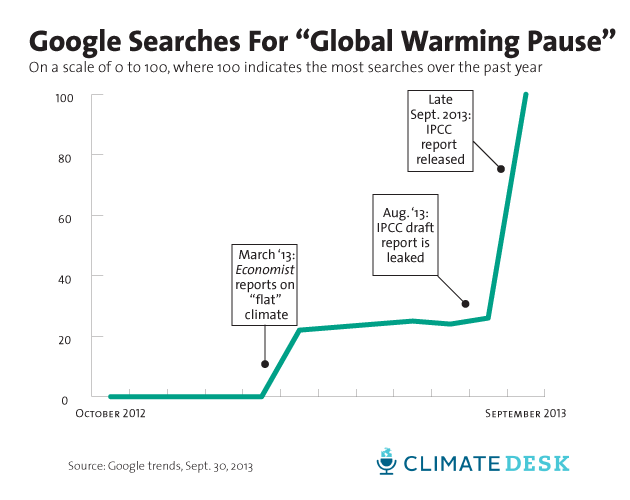

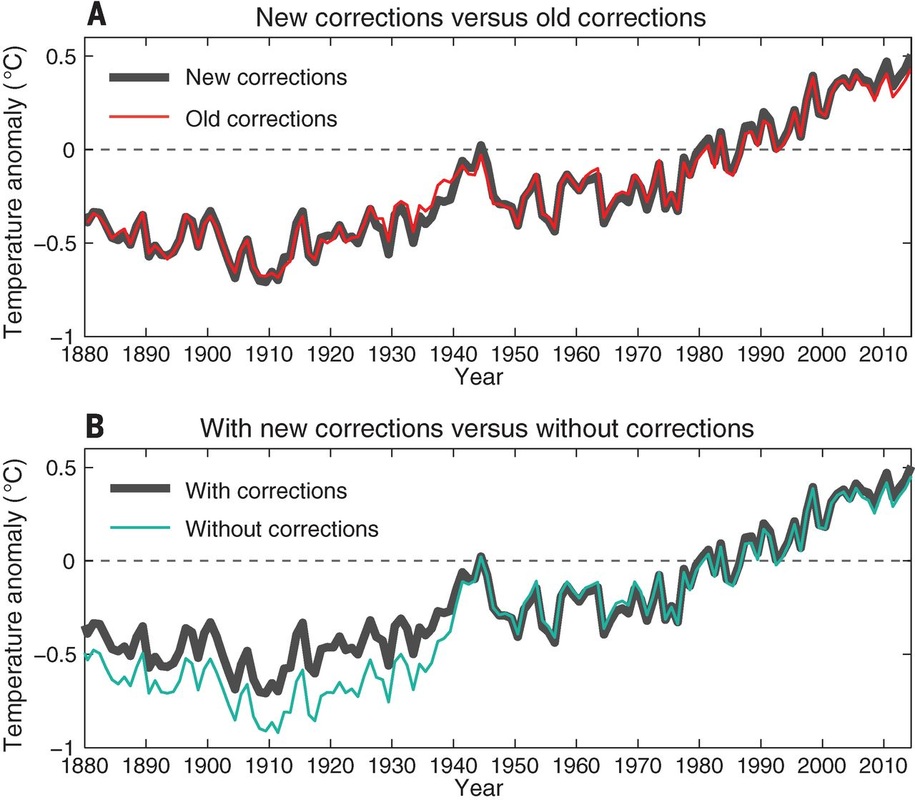

It is only September, but, absent a massive volcanic eruption or asteroid impact, 2015 will be, by far, the hottest year on the instrumental record. The culprit is a massive El Niño that is compounding the warming effects of rising greenhouse gas emissions. This year’s scorching heat will mean that the three hottest years on record will have occurred within the same five-year stretch: in 2010, 2014, and 2015. In June, scientists with the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) published a major article that measures the rate of global warming in light of this recent heat. The article uses a suite of new sources on land and across the oceans to provide a comprehensive temperature reconstruction from 1880 to the present. Many of these sources provide meteorological data of unprecedented accuracy. The new temperature reconstruction includes especially substantial corrections to previous global sea surface temperature statistics from the years 1880 to 1940. It also makes minor adjustments to temperature reconstructions of the last twenty years. In fact, using their new data, the NOAA scientists conclude that global temperatures have increased steadily since 1950. This is a major finding that contradicts the popular idea of a “pause” or “hiatus” in recent warming. According to climatologist Gavin Schmidt, director of the Goddard Institute for Space Studies, “the fact that such small changes to the analysis make the difference between a hiatus or not . . . underlines how fragile a concept [the pause] was in the first place.” So how did that pause become such an influential idea? Given the forces behind record-setting temperatures this year, it is not surprising that the answer must begin with another major El Niño, eighteen years ago. From 1997 to 1998, that record-breaking El Niño slowly uncoiled across the tropical Pacific. In an El Niño, trade winds that normally blow from east to west slow down, lowering the layer of water that divides the upper from the lower ocean. That, in turn, reduces the efficiency of cool, deep-water upwelling. Warmer sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific extend far to the east, and reshape atmospheric circulation around the world. In 1998, global temperatures rose sharply. Temperature records are usually set by a hundredth of a degree Celsius, but temperatures in 1998 exceeded the previous high-water mark by a tenth of a degree. It was the meteorological equivalent of Usain Bolt’s performance at the 2008 Olympics. Looking back in 2001, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded that the 1998 spike in Earth’s temperature was an “extreme event,” even in the context of human-caused climate change. Inevitably, global temperatures cooled in the immediate wake of the great El Niño, although they remained much higher than the twentieth-century average. Still, to some, the warnings of climate scientists had suddenly become incompatible with the recent instrumental record. The idea of the “pause” was born. Global warming sceptics quickly sought to popularize the concept. Naomi Oreskes and Eric Conway recently chronicled how some activist scientists have, for decades, derailed the public discourse on science that appears to challenge the unfettered workings of the free market. They tried to undermine, for example, science that links cigarette smoke to lung cancer, and chlorofluorocarbons to the Ozone Hole. They lost those battles, but found greater success in their fight against climate science. At every step, they have deployed the weapon of doubt. If the science that supports regulation can be made to sound uncertain, it can hardly serve as a foundation for government policy. Already in 2006, palaeontologist Robert Carter, for instance, insisted that temperatures had remained steady for eight years, since 1998. In his telling, the science behind global warming appeared anything but settled. Carter, a well-known denier of anthropogenic warming, co-authored a notorious paper in 2009, which argued that El Niño events account for most of the changes in global temperature over the past fifty years. Three years later, Carter admitted that he received a monthly salary from the Heartland Institute, an influential organization committed to denying global warming. Regardless, Carter made an error that is also committed by better-intentioned sceptics of anthropogenic climate change. He identified a climatic trend by cherry picking a past date - an abnormally warm year - that allowed him to argue for recent cooling. Even many scientists who agree with the scholarly consensus on global warming believed that the steady rise in Earth’s temperature had slowed - but not stopped - since 1998. As reported on this website, most of their research tied this supposed slowdown to one of two sets of variables. Some scientists argued that entirely natural causes had temporarily reduced the amount of solar radiation reaching the Earth. For example, as I reported on this website, one influential article blamed a recent spate of small volcanic eruptions. Other scientists more persuasively concluded that different parts of the climate system appeared to absorb more heat than had been thought possible. The oceans were widely cited as the destination for warmth that might otherwise have reached our atmosphere. Nevertheless, the so-called “pause” in global warming barely registered in the public consciousness until early 2013. In January of that year, an article by lead author James Hansen – perhaps the most responsible and vocal voice in global warming scholarship – began with alarming news. In 2012, it announced, temperatures the world over had been 0.56 degrees Celsius warmer than the 1951-1980 base average. This was in spite of a La Niña that had chilled the waters of the equatorial Pacific, and therefore had the opposite effect on global temperatures of an El Niño. Unfortunately, Hansen’s report contained a misleading and ultimately disastrous headline. Under “Global Warming Standstill,” the report noted that the five-year running mean of global temperature “has been flat for the past decade,” despite a steady (if slowing) increase in greenhouse gas emissions. The report speculated about possible reasons, but concluded that the most likely culprit was probably El Niño conditions early in the period, followed by La Niña episodes in more recent years. In years less troubled by these conditions, temperatures continued to rise at the rate they had in the previous three decades. In March, an influential piece in The Economist misinterpreted this part of Hansen’s article. It began by declaring that, “over the past 15 years, air temperatures at the Earth’s surface have been flat while greenhouse-gas emissions have continued to soar.” The article did not deny the existence of warming, and concluded that the recent pause was “hardly reassuring.” Nevertheless, it suggested that Earth might be less sensitive to our carbon emissions than scientists had previously believed. The Hansen article, remember, had reached entirely different conclusions. The Economist article provided an opening for sceptics of climate change to push the narrative of the unexplained pause. Meanwhile, as chronicled by Chris Mooney, the IPCC prepared to release its fifth assessment report. In August, a leaked draft was released to the press. It contained descriptions of the pause that, when read in isolation, appeared to confirm the Economist article. According to one of the report’s lead authors, Dennis Hartmann of the University of Washington, public pressure convinced the scientists that they “had to say something” about the pause. They were hesitant, because the fifteen years between 1998 and 2013 were too short to reliably reflect a climatic trend. Yet before they had finalized their interpretation of the pause, it reached journalists who were only too eager to sacrifice scientific accuracy for sensationalistic headlines. Not all proponents of the pause were scientifically illiterate, or associated with global warming denial. For example, in September 2013, Berkeley physicist and converted climate sceptic Richard Muller announced that the “global warming crowd has a problem,” because, “despite a steady escalation of greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere, the planet’s average surface temperature has remained pretty much the same for the last 15 years.” Muller argued that he had more or less predicated this pause back in 2004. It was in a critique of the so-called “hockey stick” graph that famously illustrated global warming (and has been recently vindicated). In 2004, Muller warned that, were the graph taken seriously, many would see inevitable, natural variations in temperature as undermining the case for anthropogenic climate change. In 2013, it seemed that Muller might be right. Then, in late September, the IPCC finally released its completed fifth assessment report. As I described on this website, the report acknowledged a slight slowdown in the rate of global warming from 1998 to 2012. However, it weakened the previous draft’s description of a “pause” or “hiatus.” It confirmed that every decade in the past thirty years had been successively warmer than any previously recorded decade. As I wrote in 2013, it also explained that “the presence of short-term fluctuations in climate does not throw into doubt the existence of long-term climatic trends.” As one might expect, many sceptics met the final report with derision. Fast forward to the present, and 2015 is set to be another meteorological equivalent of Usain Bolt's Olympic run. As in 1998, it looks like the previous record temperature will be broken by a tenth of a degree Celsius. Perhaps the narrative of the pause is now on its deathbed. Yet the idea of a recent slowdown in warming persists in very informed circles. In an elegant article published in the journal Science, climatologist Kevin Trenberth responds to the NOAA paper by taking issue with any warming trend that starts in 1950. After all, this was at the beginning of a so-called “big hiatus” in warming that chilled the world between 1943 and 1975. If sceptics should not cherry pick the start date of their temperature series by choosing an abnormally warm year, climatologists should not do the same by selecting a very cold year.

Interestingly, the big hiatus, which is well supported by robust science, was probably also caused by human activity. Aerosols released into the atmosphere by human pollution probably cooled the world, until clean air acts were passed in the 1970s. In the past, anthropogenic climate change could warm or cool the globe, and involve many kinds of human activity. Overall, Trenberth supports the major findings of the NOAA scientists. He argues that there may have been a slight slowdown – not a pause – in the rate of global warming, driven at least partially by natural variation in, for example, the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (which includes El Niño and La El Niña). Yet he agrees that temperatures are rising quickly once again, and that the slowdown has probably ended. Earlier this year, record-breaking wildfires spread across North America, while heat waves killed thousands in Europe and India. Sea levels, it seems, are warming and rising much faster than even the IPCC had predicated. The costs of climate change inaction have become increasingly clear. Carbon emissions have stagnated or declined in many developed countries, yet it is far from enough. Without drastic action, the weather of 2015 is only a precursor of things to come. ~Dagomar Degroot Sources: Hansen, J., M. Sato, and R. Ruedy. "Global Temperature Update Through 2015." 15 January, 2013. Available at: http://www.columbia.edu/~jeh1/mailings/2013/20130115_Temperature2012.pdf Karl, Thomas R. et al. "Possible artifacts of data biases in the recent global surface warming hiatus." Science 348: 6242 (2015): 1469-1472. Trenberth, Kevin E. "Has there been a hiatus?." Science 349: 6249 (2015): 691-692. Trenberth, Kevin E. "The definition of El Nino." Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 78: 12 (1997): 2771-2777. |

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed