Archived Feature Articles

Six Droughts between 1302 and 1306: A "1300s Event"?

Recently coined the “1310s event," the wet anomaly of the 1310s has attracted a lot of attention from scholars. More

Pandemics, Empires, and the Lessons of History

In the 17th episode of Climate History, co-hosts Dagomar Degroot and Emma Moesswilde interview PhD candidate Emily Webster of the Department of History at the University of Chicago. Webster's trailblazing scholarship combines environmental history, the history of science, and medical history to transform understandings of disease in the British Empire. More

Historical Climate Data Can Improve Our Assessment of Future Climate Risk

Australia is a land characterised by dramatic climate and weather extremes. Currently, our understanding of the nation’s climatic history is mostly confined to official records kept by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology that begin in 1900, despite the fact that observations are available from first European settlement of Australia in 1788. More

A Hungry Winter: Colonialism in a Cold Climate

Times of hunger and starvation were part of life for northern Indigenous peoples. Dene, Inuvialuit, and Gwich’in shared lessons about planning to avoid starvation, the need to show proper respect and gratitude for good hunts and successful fishing, and how to eat after a period of hunger. More

A Conversation with Timothy Newfield: Pandemics, Climate Change, and What History Reveals About Today's Biggest Challenges

In the 16th episode of Climate History, co-hosts Dagomar Degroot and Emma Moesswilde interview professor Timothy Newfield, a climate historian and historical epidemiologist in the departments of history and biology at Georgetown University. More

A Conversation with Kathryn de Luna: Reimagining University Education for Today's Multidisciplinary Problems

In the 15th episode of Climate History, co-hosts Dagomar Degroot and Emma Moesswilde interview Kathryn de Luna, Provost's Distinguished Associate Professor in the Department of History at Georgetown University. More

The good, bad, undefined Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA), a climatic phase that overlapped with the late-medieval and early modern periods, increasingly interests historians - academic and popular alike. Recently, they have tied the LIA to the outbreak of wars, famines, economic depressions and overall troublesome times. More

A Conversation with Joseph Manning: Climate Change in the Ancient World

In the 14th episode of Climate History, co-hosts Dagomar Degroot and Emma Moesswilde interview Joseph Manning, the William K. and Marilyn Milton Simpson Professor of Classics at Yale University. More

A Conversation about COVID-19: Reflections on the Pandemic, the Past, and the Future

In the 13th and most unusual episode of Climate History, our podcast, co-hosts Dagomar Degroot and Emma Moesswilde share their reflections on the COVID-19 pandemic. More

The Legal Structure of the Paris Agreement – Flexible and Fit or Fragile and Fading?

As we enter the 2020s, the backdrop of the climate crisis remains grim. Recent scientific reports tell us that global greenhouse gas emissions are increasing, not declining as they need to. More

A Conversation with Valerie Trouet and Amy Hessl: What Tree Rings Reveal About Climate Change

In the 12th episode of Climate History, co-hosts Dagomar Degroot and Emma Moesswilde interview professors Amy Hessl and Valerie Trouet: leading paleoclimatologists who scour the Earth to measure the growth rings in trees. More

Are Surveyors' Maps and Journals an Untapped Source for Climate Scientists?

In early nineteenth century Australia, surveyors were given a near impossible task by colonial authorities. They were asked to use their expeditions to ascertain "the general nature of the climate, as to heat, cold, moisture, winds, rains, periodical seasons." More

A Conversation with Victoria Herrmann: Activism and Storytelling in a Warming World

In the 11th episode of Climate History, co-hosts Dagomar Degroot and Emma Moesswilde interview Victoria Herrmann, president and managing director of the Arctic Institute and one of Apolitical's top 100 influencers on climate policy. Dr. Herrmann's scholarship has focused on media representations of the Arctic and its peoples. More

A Conversation with Bathsheba Demuth: Histories of the Changing Arctic

In the tenth episode of Climate History, our podcast, Emma Moesswilde and Dagomar Degroot interview Bathsheba Demuth, assistant professor of environmental history at Brown University. Her new book, Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait is now out with Norton, and has received rave reviews in both popular and academic publications. More

A Conversation with Kevin Anchukaitis: Past Climate Change and Why It Matters Today

In the ninth episode of Climate History, our podcast, we relaunch with a new co-host: Emma Moesswilde, PhD Student in Environmental History at Georgetown University. For the relaunch, Moesswilde and Dagomar Degroot are joined by Kevin Anchukaitis, associate professor of geography at the University of Arizona and one of the world's leading paleoclimatologists. More

Remembering Disaster: How Qing Dynasty Records Reveal Connections Between Memory and Environment

Memory is one of the most powerful parts of the human psyche. It can help us make sense of the world around us, but it can also cloud our vision. Over long timeframes, memory can actually become embedded into a culture in ways that are difficult to comprehend. One of the complex effects of this sort of cultural memory may be the development of a culture of resilience in the face of extreme climatic events. More

Bird Migration, Climate Change, and History

On May 11, birders in 130 countries took part in World Migratory Bird Day (WMBD). This citizen science and conservation project enrolls professional and amateur ornithologists twice a year—in May and October—to record sightings of hundreds of species during their spring and fall passages through continental and hemispheric regions, or so-called flyways, across Africa, Europe, Asia, the Americas, and Australasia. More

Does the United States Need a Climate Refugee Policy?

People displaced by extreme weather events and slower-developing environmental disasters are often called “climate refugees.” The term “refugee,” however, has a very precise meaning in US and international law and that definition limits those who can be admitted as refugees and asylees. Calling someone a “refugee” does not mean that they will be legally recognized as such and offered humanitarian protection. More

More: Energy History and Energy Futures

If nuclear power is to be used as a stop-gap or transitional technology for the de-carbonization of industrial economies, what comes next? Energy history could offer new ways of imagining different energy futures, but current scholarship offers linear narratives of growth toward the development of high-energy economies, leaving little room to imagine low-energy futures. More

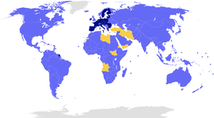

The Nuclear Renaissance in a World of Nuclear Apartheid

Nuclear power is back, riding on growing fears of catastrophic climate change. The climate crisis has rekindled heated debate over the advantages and disadvantages of nuclear power. However, advocates and opponents alike tend to overlook or downplay a unique risk that sets atomic energy apart from all other energy sources: proliferation of nuclear weapons. More

The Cold War Constraints on the Nuclear Energy Option

Shortly before uranium miner Gus Frobel died of lung cancer in 1978 he said, “This is reality. If we want energy, coal or uranium, lives will be lost. And I think society wants energy and they will find men willing to go into coal or uranium.” Frobel understood that governments had crunched the numbers. They had calculated how many miners died comparatively in coal and uranium production to produce energy. More

Only Dramatic Reductions in Energy Use Will Save The World From Climate Catastrophe

There is no longer any debate. Humanity sits at the precipice of catastrophic climate change caused by anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Recent reports provide clear assessments: to limit global warming to 1.5ºC above historic levels, thereby avoiding the most harmful consequences, governments, communities, and individuals around the world must take immediate steps to decarbonize their societies and economies. More

Did Colonialism Cause Global Cooling? Revisiting an Old Controversy

Roughly 11,000 years ago, rising sea levels submerged Beringia, the vast land bridge that once connected the Old and New Worlds. Vikings and perhaps Polynesians briefly established a foothold in the Americas, but it was the voyage of Columbus in 1492 that firmly restored the ancient link between the world’s hemispheres. Plants, animals, and pathogens – the microscopic agents of disease – never before seen in the Americas now arrived in the very heart of the western hemisphere. More

Next Generation Nuclear?

Climate change is here to stay. So too for the next several millennia is radioactive fallout from nuclear accidents such as Chernobyl and Fukushima. Earthlings will also live with radioactive products from the production and testing of nuclear weapons. The question as to whether next generation nuclear power plants will be “perfectly safe” appears to decline in importance as we consider the catastrophic outcome of climate change. More

Closing Nuclear Plants Will Increase Climate Risks

On March 28, 1979, I woke up late and rushed to catch the bus to my suburban high school in Rockville MD. So it wasn't until I found my friends clustered around the radio in the cafeteria that I learned seventy-seven miles upwind of us, Three Mile Island Reactor Unit 2 was in partial meltdown. More

Environmental Historians Debate: Can Nuclear Power Solve Climate Change?

This series focuses on what environmental and energy historians can bring to discussions about nuclear power. It is a tripartite effort between Active History, the Climate History Network (CHN), and the Network in Canadian History and Environment (NiCHE), and will be cross-posted across all three platforms. The series is co-edited by a member of each of those websites: professors Jim Clifford, Dagomar Degroot, and Daniel Macfarlane. More

Reconstructing Africa's Climate: Solving the Riddle of Rainfall

To grasp the significance of global warming, and to confirm its connection to human activity, you have to know how climate has changed in the past. Scholars of past climate change know that understanding how climate has varied over historical timescales requires access to robust long-term datasets. This is not a problem for regions such as Europe and North America, which have a centuries-long tradition of recording weather with instruments. More

Two Decades from Disaster? The IPCC's "Global Warming of 1.5° C"

International climate change agreements have long aimed at limiting anthropogenic global warming to 2°C Celsius, relative to so-called “pre-industrial” averages. Yet in early 2015, more than 70 scientists contributed to a report that warned about then-poorly understood dangers of warming short of 2° C. Several months later, Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) met in Paris and reached an agreement to keep global warming to “well below” 2° C. The Paris Agreement invited the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to prepare a special Assessment Report. More

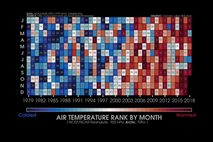

Is There a Better Way To Do Climate History? Testing a Quantitative Approach. August 32, 2018.

Until recently, it was notoriously difficult to connect today’s extreme weather with the gradual trends of climate change. Scientists shied away from saying, for example, that catastrophic droughts or severe hurricanes reflected the influence of anthropogenic global warming. More

Are Woodland Caribou Doomed by Climate Change? July 26, 2018.

In May 2018, woodland caribou were declared functionally extinct in the United States. Across the Canadian north, woodland caribou have disappeared from roughly half their 19th century range. Is climate change dooming woodland caribou? Or are managers using climate change as an excuse to avoid making difficult policy decisions? More

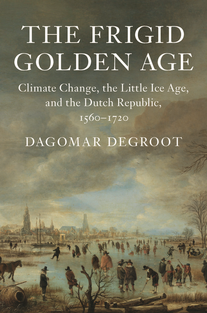

A Conversation with Dr. Dagomar Degroot: Resilience and Adaptation in the Little Ice Age. June 15, 2018.

In the eighth episode of the Climate History Podcast, PhD candidate Robynne Mellor (Georgetown University) interviews Dr. Dagomar Degroot, director of HistoricalClimatology.com, about his new book: The Frigid Golden Age: Climate Change, the Little Ice Age, and the Dutch Republic, 1560-1720. Dr. Degroot is an assistant professor of environmental history at Georgetown University, where his research focuses on societal adaptation and resilience to climate change, and the environmental history of outer space. More

Ecological Militarism: The History of the Military’s Relationship with Climate Change. May 25, 2018.

Many historians have discussed the influence of the Cold War on the development of specific disciplines within the broader field of earth science. However, few have touched on U.S. military’s study of climate change, an interest that accelerated during the Cold War. The decades-long studies sponsored by the Departments of Defense and Energy in the Cold War produced led to many attempts to transform the earth itself into a political and environmental weapon. More

Introducing the Tipping Points Project. April 30, 2018.

In late 2016, Randall Bass, vice provost for education at Georgetown University, asked me to help design and teach a pilot project at Georgetown University that would experiment with a new way of introducing climate change to undergraduate students. The Core Pathway on Climate Change initiative, as we came to call it, allowed students to mix and match seven-week courses - "modules" - to find their own pathway through the scholarship of climate change. More

North Atlantic Right Whales From Their Medieval Past To Their Endangered Present. March 21, 2018.

2017 was a calamitous year for the North Atlantic right whale. The final count of the 2017 "Unusual Mortality Event" was eighteen animals. Fourteen North Atlantic right whales were found dead from the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to Cape Cod between June and December, with an additional four strandings and entanglements through the year. More

A Frigid Golden Age: Can the Society of Rembrandt Teach Us About Global Warming? February 27, 2018.

Earth’s climate is changing with terrifying speed. Humanity has strengthened a greenhouse effect that has now warmed the planet by roughly one degree Celsius. The scale, speed, and causes of today’s global warming have no precedent, but of course natural forces have always changed Earth’s climate. We now know that these changes were big enough to shape the fates of past societies. Most confronted disaster, but a few seemed to prosper in spite of – and in some cases because of – climate changes. Perhaps the most successful of all emerged in the coastal fringes of the present-day Netherlands. More

Icebreaking in the Gulf of Bothnia: A Passenger’s Perspective. January 11, 2018.

This past winter I was fortunate to join the Arctia Otso icebreaker in the Gulf of Bothnia, Finland, from March 2 to March 24, 2017. I had sailed the Northwest Passage aboard the Canadian Coast Guard ships Sir Wilfrid Laurier and Louis S. St-Laurent in 2015. Going to Finland to travel on an icebreaker for 20 days was my next big step as a Canadian scientist. More

Looking Back, Looking Forward: A Historian Goes to COP23. December 21, 2017.

I joined the most recent UN Climate Change Conference in Bonn with a delegation from Monash University, which also included legal scholars, renewable energy specialists, and science communicators. The opportunity to observe and participate in the activities that accompany the negotiations was too good to pass up. More

Volcanoes, Climate Change, and Society: History and Future Prospects. November 30, 2017.

In June 1783, the residents of Kirkjubæjarklaustur, an Icelandic village, watched as the water of their local river Skaftá vanished and, days later, was replaced by a “fiery flood” of lava. They could not have imagined that this event would have consequences halfway around the globe, all the way to eastern Africa. More

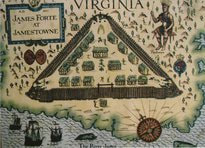

New Worlds of Climate Change: The Little Ice Age and the Colonization of America. October 13, 2017.

In August 1559, the aspiring conquistador Tristán de Luna y Arellano brought some five hundred soldiers and a thousand colonists from New Spain to a settlement on Pensacola Bay, Florida, which he declared “the best port in the Indies.” The viceroy of New Spain reported to the king “the port is so secure that no wind can do them any damage at all.” Even as he wrote, a hurricane was entering the Caribbean, poised to devastate Puerto Rico. A week later, it roared into Pensacola Bay. Tristán de Luna had no experience of tropical storms that could overwhelm even the strongest harbors. More

Weather, Climate Change, and Inuit Communities in the Western Canadian Arctic. October 5, 2017.

Global climate change brings with it local weather that communities and cultures have difficulty anticipating. Unpredictable and socially impactful weather is having negative effects on the subsistence, cultural activities, and safety of indigenous peoples in Arctic communities. More

“Lighthouses in the Empire”: History of Ice and Place in the “Mountains of the Moon," Uganda. September 9, 2017.

Mount Emin. Mount Baker. Mount Stanley. It is rare for a location to excite so many disparate sensibilities, but the post-colonial scholar, glaciologist, botanist, and climate scientist find themselves welcome bedfellows in the Rwenzori Mountains of central Africa. More

Will Climate Change Cause Conflict in the Arctic? Searching for Answers in the Past. July 25, 2017.

In article after article, academics, policy analysts, and journalists have told a similar story: climate change, by melting Arctic ice, is unlocking resources that could soon trigger war in the far north. They argue that the race to extract the reservoirs of oil and natural gas that lie under the vanishing ice will provoke hostilities between nations eager to claim the bonanza. More

Weather Markets: Accounting for Climate in Early American Agri-business. June 22, 2017.

When Monsanto spent $1 billion in 2013 to purchase Climate Corporation, its climate data, and its algorithms for using machine learning to predict weather, everyone from farmers to The New Yorker concluded that agri-business believed the climate science consensus: climate change is real and it introduces real risks to business. More

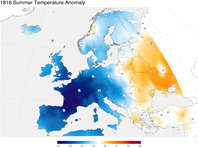

“Bread or Blood”: Climate Insecurity in East Anglia in 1816. May 17, 2017.

The recent bicentenary of the Year without a Summer (1816) has brought that unusual intersection of geological forces, changing climate, and human history into focus again. The radical cooling brought on by Tambora’s eruption seems especially significant as modern societies face their own dramatic climate change. More

A Conversation with Dr. Bathsheba Demuth: Capitalism, Communism, and Indigenous Communities in a Changing Arctic. April 6, 2017.

In the seventh episode of the Climate History Podcast, Dr. Dagomar Degroot interviews a fast-rising star in the field of environmental history: Dr. Bathsheba Demuth, assistant director of HistoricalClimatology.com and the Climate History Network. Dr. Demuth is an assistant professor at Brown University, where she specializes in the history of Arctic lands and seas. More

Iceberg Utilization: A Panacea for a Thirsty World? March 27, 2017.

Iceberg Utilization: A Panacea for a Thirsty World? 3/24/2017 5 Comments Dr. Ruth Morgan, Monash University Picture Non-tabular iceberg off Elephant Island in the Southern Ocean. Source: Andrew Shiva, Wikipedia. Ice, or a lack of it, is an “icon” of anthropogenic climate change. Earlier this year, researchers reported that a rift in Antarctica’s fourth-largest ice shelf has accelerated and could soon cause a vast iceberg to fall into the sea. After the collapse of the ice shelf, the glaciers that once sustained it will run into the sea. More

A Conversation with Dr. James Fleming: Geoengineering and Atmospheric Science. March 9, 2017.

In the sixth episode of the Climate History Podcast, Dr. Dagomar Degroot interviews one of the world's best-known historians of science: Dr. James Fleming, the Charles A. Dana Professor of Science, Technology, and Society at Colby College. Professor Fleming is perhaps the leading historian of meteorology and climatology. He has degrees in astronomy, atmospheric science, and history, and he is the founder and first president of the International Commission on History of Meteorology. More

"A Grande Seca": El Niño and Brazil’s First Rubber Boom. February 7, 2017.

People care about climate change when it affects them. That is why Pacific islanders fear rising sea levels more than the average American, and why many who live in coastal cities fear a projected increase in tropical cyclones more than those further inland. Yet the idea that an environmental change “over there” will not affect communities “here” makes little sense. More

Climate History Network Statement on U.S. Executive Order and Climate Policy. February 2, 2017.

The Climate History Network is an organization with more than 200 members in universities and governments around the world. As an international network dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge, we are committed to the free flow of information and people. We celebrate the diversity of our members and recognize that all have an equal voice and deserve equal rights, regardless of age, gender, race, ethnicity, physical abilities, sexual orientation, religion, or country of origin. We believe that these principles are essential not only to good scholarship, but also to a healthy democracy. More

A Conversation with Dr. Sam White: Trump, the Little Ice Age, and Mapping Climate History. January 31, 2017.

In the fifth episode of the Climate History Podcast, Dr. Dagomar Degroot interviews Dr. Sam White of Ohio State University, the co-founder and co-director of the Climate History Network. Professor White is a leading environmental historian of the Little Ice Age, a period of global cooling that lasted from the thirteenth through the nineteenth centuries. More

Teaching Climate Change by Combining the Humanities and Sciences. January 3, 2017.

Most students at Brown University know Professor Kathleen Hess from the two-semester challenge of organic chemistry. But in a class that debuted this fall, “Exploration of the Chemistry of Renewable Energy,” Dr. Hess blended the tools of her discipline with questions of human impacts on the climate, renewable energy technologies, and the social impact of how energy is generated and used. More

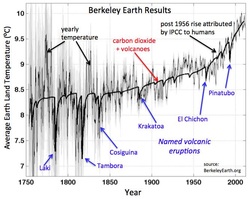

Volcanoes, Comet Crashes, and Changes in the Sun: How Cooling Transformed the World. December 3, 2016.

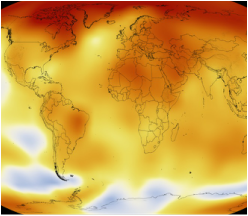

The world is warming, and it is warming fast. According to satellites and weather stations, Earth's average annual temperature will smash the instrumental record this year, likely by around 0.1° C. Last year, global temperatures broke the record by around the same amount. That may not seem impressive, but consider this: temperatures have climbed by about 0.1° C per decade since the 1980s. In just two years, therefore, our planet catapulted two decades into a hotter future. More

Towards a Messy History of Dearth and Climate in Carolingian Europe. November 14, 2016.

Will climate change trigger widespread food shortages and result in huge excess mortality in our future? Many historians have argued that it has before. Anomalous weather, abrupt climate change, and extreme dearth often work together in articles and books on early medieval demography, economy and environment. Few historians of early medieval Europe would now doubt that severe winters, droughts and other weather extremes led to harvest failures and, through those failures, food shortages and mortality events. More

A Conversation with Bruce Campbell. October 31, 2016.

Bruce Campbell is a highly respected historian of medieval economic history. In his long and distinguished career at Queen's University, Belfast, he has belonged to the Departments of Geography, Economic History, History, and the School of Geography, Archaeology and Palaeoecology. Recently, he published a major new book: The Great Transition: Climate, Disease and Society in the Late-Medieval World. The book transforms how historians have understood the quintessential crisis of Western society - its apparent collapse in the fourteenth century - by rooting it in environmental forces. More

A Conversation with J. R. McNeill. September 30, 2016.

For the fourth episode of the Climate History Podcast, Dr. Dagomar Degroot interviews one of the world's leading environmental historians: Dr. John R. McNeill of Georgetown University. Professor McNeill has authored or co-authored six books, and edited or co-edited twelve. He is perhaps best known for Something New Under the Sun: An Environmental History of the Twentieth-Century World. More

What Made the Thule Move? Climate and Culture in the High Arctic. September 13, 2016.

In the year 1001 CE, Leif Erikson made landfall in Greenland, and traded with people who “in their purchases preferred red cloth; in exchange they had furs to give.” The Vikings called these people Skraelings. Present-day archeologists and historians call them the Thule. At its height, Thule civilization spread from its origins along the Bering Strait across the Canadian Arctic and into to Greenland. The ancestors of today’s Inuit and Inupiat, the Thule accomplished what Erikson and subsequent generations of Europeans never managed: living in the high Arctic without supplies of food, technology, and fuel from more temperate climates. More

The “Dantean Anomaly” Project: Rapid Climate Change in Late Medieval Europe. August 27, 2016.

In the last years of his life, Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) was an unsuspecting witness to a rapid shift in climatic conditions that led to cooler and wetter weather all over the continent. Perhaps it was not by chance that in his Inferno, finished in 1314, the sinners guilty of gluttony and sent to the third circle of hell were punished by incessant cold rain, hail and snow, while squirming through foul-smelling mud that reminded contemporaries of the crops rotting on their fields. Across Europe, meteorological events in the 1310s caused harvest failures, floods, famines, and mass deaths. In particular, Dante’s description of the wet third ring of hell is very similar to weather conditions that caused famine in Italy between 1310-12, and offers a prominent clue the onset of the Little Ice Age left in Europe’s cultural heritage. More

A Conversation with Valérie Masson-Delmotte: Part II, IPCC and Public Outreach. August 1, 2016.

Contributing editor Benoit Lecavalier recently conducted an extensive interview with Valérie Masson-Delmotte, one of the world's leading climate scientists and the lead coordinating author for Working Group One, the Physical Scientific Basis, in the next IPCC Assessment Report. More

A Conversation with Valérie Masson-Delmotte: Part I, Climate Science. July 19, 2016.

Valérie Masson-Delmotte is an internationally renowned climate scientist. She was a lead author for the "paleoclimate" section of the fourth assessment report published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). She was the lead coordinating author for the "information from paleoclimate archives" section in the IPCC's fifth and most recent assessment report. For the IPCC's upcoming sixth assessment report, she is a lead coordinating author for the entire Working Group One, the Physical Scientific Basis, which oversees all other scientific chapters.

At the recent Second Open Science Conference of the International Partnerships in Ice Core Sciences, in Tasmania, our contributing editor, Benoit Lecavalier, conducted a lengthy interview with Dr. Masson-Delmotte. Later this month, we will publish Part II, on public outreach on the future of the IPCC. More

At the recent Second Open Science Conference of the International Partnerships in Ice Core Sciences, in Tasmania, our contributing editor, Benoit Lecavalier, conducted a lengthy interview with Dr. Masson-Delmotte. Later this month, we will publish Part II, on public outreach on the future of the IPCC. More

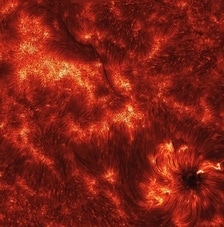

Resurrecting Maunder’s Ghost: The Rediscovery of the Maunder Minimum. June 29, 2016.

Counting in everyday life is a relatively straightforward affair; one, two, three, and on and on. Less simple is the process of reliably counting the number of sunspots on the surface of the sun. Sunspots are darkened areas on the solar surface. In Europe, people knew of their existence at least since the early 17th century, and some of the larger sunspots were probably noted long before Galileo. Elsewhere, sunspot counts were maintained for much longer. Counting these darkened areas is one of the most effective ways to establish a record of the evolution in solar behavior. Not only do sunspot observations provide crucial information about changes in the sun’s magnetic field, they strongly correlate with long-term fluctuations in the amount of energy released by the sun – the so-called solar cycle. More

What was the Maunder Minimum? New Perspectives on an Old Question. June 9, 2016.

Although it may seem like the sun is one of the few constants in Earth’s climate system, it is not. Our star undergoes both an 11-year cycle of waning and waxing activity, and a much longer seesaw in which “grand solar minima” give way to “grand solar maxima.” During the minima, which set in approximately once per century, solar radiation declines, sunspots vanish, and solar flares are rare. During the maxima, by contrast, the sun crackles with energy, and sunspots riddle its surface. The most famous grand solar minimum of all is undoubtedly the Maunder Minimum, which endured from approximately 1645 until 1720. It was named after Edward Maunder, a nineteenth-century astronomer who painstakingly reconstructed European sunspot observations. More

Clio and Climate: On Saving and Researching a Climate History Archive. May 16, 2016.

In 2008, I had a meeting at the Environment Canada headquarters in Downsview, Ontario, and afterward staff gave me a tour. Since I’m a historian, they showed me the old stuff. Down in the basement – not quite the warehouse scene at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark, but close enough – they led me along row after row of weather observations: all of the original paper forms and registers that since 1840 had been filled out by what would eventually be thousands of observers at thousands of weather stations across Canada. Environment Canada had long ago squeezed the quantitative data they wanted from the observations, and from it created an online National Climate Data and Information Archive. That may have actually put the physical collection more at risk; a teary librarian told of worrying she would return from vacation someday and find it had been thrown out. Staff were maintaining the collection as best they could, but they knew the facility was not up to archival standards – a massive steam pipe loomed menacingly nearby – and they were concerned about the lack of a long-term plan for it. More

The Global Cooling Event of the Sixth Century. Mystery No Longer? May 2, 2016.

The June 1991 Pinatubo eruption in the Philippines was one of the largest volcanic eruptions of the twentieth century. It is well documented. There are living witnesses, newspaper articles, detailed surveys of the mountain before and after it blew its top, and satellite maps of the ejecta. The eruption was photographed from the ground and the air, and today you can even YouTube it. More

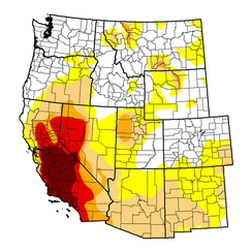

Contextualizing Western Drought. April 18, 2016.

At the 2016 American Society of Environmental History conference in Seattle, I joined Linda Nash (University of Washington), Char Miller (Pomona College), and Libby Robin (The Australian National University) to contextualize Western drought in environmental, historical and cultural terms. ‘Western drought’ in this instance referred to the region that the US Drought Monitor classifies as ‘West’, where some areas are still experiencing ‘exceptional’ drought conditions. More

Did the Spanish Empire Change Earth's Climate? February 29, 2016.

Ask most people about climate change, and you will soon find that even the relatively informed make two big assumptions. First: the world’s climate was more or less stable until recently, and second: human actions started changing our climate with the advent of industrialization. More

A Conversation about Archaeology in the Arctic. January 17, 2016.

For the third episode of the Climate History Podcast, Dr. Dagomar Degroot interviews two leading archaeologists of the medieval and early modern Arctic: Dr. Thomas McGovern of the City University of New York, and Dr. George Hambrecht of the University of Maryland College Park. More

Teaching Climate History in a Warming World. December 17, 2015.

This semester, I taught my first course devoted exclusively to the environmental history of climate change. The course was, as one of my senior auditors pointed out, unusually ambitious. Luckily, I had a group of brilliant, hard-working students who embraced its challenges. Their coursework included a fifteen-page essay that connected a change in past global or regional climates to an episode in human history. They had to find a topic and then use a primary source to make an argument about that topic. They needed to support their argument using a blend of scientific and humanistic scholarship. The results were impressive, and you can read some of the abstracts here. More

Assessing the Future During COP21. November 30, 2015.

This week, roughly 40,000 delegates from 147 nations gather in Paris for the twenty-first annual "Conference of Parties" (COP21) in the fight against climate change. For the first time, participating governments will seek a legally binding agreement on mitigating and adapting to climate change. Their ambition will be to ensure that average global temperatures do not rise more than two degrees Celsius above their preindustrial averages. However, this goal now faces at least four serious challenges. More

A Conversation with Sam White. November 17, 2015.

For the second episode of the Climate History Podcast, Dr. Dagomar Degroot interviews the co-founder and co-administrator of the Climate History Network: Dr. Sam White of Ohio State University. Professor White is one of the most innovative and respected environmental historians of the "Little Ice Age," a period of climatic cooling that, according to some definitions, affected most of the world from the fourteenth through the nineteenth centuries. More

Lessons From the Storm that Wasn't. October 10, 2015.

Last week, millions of people across the eastern coasts of the United States and Canada faced a frightening prospect: landfall of a major hurricane to rival Sandy, or perhaps even Katrina. At noon on October 1st, Hurricane Joaquin churned over Samana Cay, the largest uninhabited island in the Bahamas, and perhaps the first land glimpsed by Columbus in 1492. More

Whatever Happened to the Global Warming "Pause?" September 2, 2015.

It is only September, but, absent a massive volcanic eruption or asteroid impact, 2015 will be, by far, the hottest year on the instrumental record. The culprit is a massive El Niño that is compounding the warming effects of rising greenhouse gas emissions. This year’s scorching heat will mean that the three hottest years on record will have occurred within the same five-year stretch: in 2010, 2014, and 2015. More

A Conversation with Geoffrey Parker. July 23, 2015.

More and more people are recognizing that, to understand climate change today, we must study its past. The study of past climates has never been more popular or more interdisciplinary, and its findings are increasingly reaching the media. Policymakers are taking notice - although not always in ways we would like - and the general public is, too. In fact, this site now attracts around 100,000 visitors annually, and we hope to build on that number as we add new features and content. To that end, we are launching a new Climate History Podcast on iTunes. Within days, you will be able to search for it on iTunes, but you can already subscribe by clicking on this link. More

Is Climate Change Behind the Syrian Civil War?July 8, 2015.

Across much of the world, climate change is making, or will soon make, environments less capable of supporting human life. Anyone who has seen the movie Mad Max will be familiar with the assumption that a hotter, and, in some places, drier climate will drive people to greater competition. When that competition is for the essentials of life, and there is not enough to go round, people resort to violence. In short: global warming could make war even more common than it is today. More

A Conversation with Miranda Massie. June 1, 2015.

Climate change might be the most important issue the world faces today. Readers of this site will know it has a rich history. It helped trigger the evolution of sentience in primates, created conditions that encouraged agriculture, and influenced the rise and fall of civilizations from Bronze Age Greece to the Ottoman Empire. Its present, as we have recently been reminded, affects us all. In just the last week, dozens have died in Texan floods, hundreds in an Indian heat wave, and thousands in a Syrian war provoked, in part, by drought. The future looks even more alarming. The IPCC and WMO have both warned that the world, and our place in it, may be almost unrecognizable in a century. So why is there no climate change museum? More

Heading North for the Arctic Winter. April 20, 2015.

By Benoit S. Lecavalier.

In early February, I had the opportunity to gather with fellow scientists in Longyearbyen, the most northerly permanent village in the world. The town is in the Norwegian Archipelago of Svalbard at approximately 80°N latitude, slightly over a 1,000 km from the North Pole. For that reason, it is the perfect place to explore the key issues currently facing the glaciological community. The most important: how do glaciers and large ice sheets respond to climate change, and affect global sea levels? This question can only be answered by unravelling complex relationships with potentially dire consequences for our civilization. More

In early February, I had the opportunity to gather with fellow scientists in Longyearbyen, the most northerly permanent village in the world. The town is in the Norwegian Archipelago of Svalbard at approximately 80°N latitude, slightly over a 1,000 km from the North Pole. For that reason, it is the perfect place to explore the key issues currently facing the glaciological community. The most important: how do glaciers and large ice sheets respond to climate change, and affect global sea levels? This question can only be answered by unravelling complex relationships with potentially dire consequences for our civilization. More

Towards a Climate History of the Solar System. March 6, 2015.

Climate historians explore how climate change influenced human history. Until now, their research has investigated environmental changes on Earth, and with good reason. Many examine how climate change affected human beings in centuries when space travel could scarcely be imagined. Others are too concerned with contextualizing global warming to consider environments beyond Earth. However, recent breakthroughs in scientific understandings of Mars’s watery past suggest that climate history can, and should, expand into the Solar System. More

Climate Change Scepticism: Interdisciplinarity Gone Wrong? February 12, 2015.

This site explores interdisciplinary research into climate changes past, present, and future. Its articles express my conviction that diverse approaches, methodologies, and findings can yield the most accurate perspectives on complex problems. To contextualize modern warming, for example, we can reconstruct past climate change using models developed by computer scientists; tree rings or ice cores examined by climatologists; and documents interpreted by historians. More

Is Arctic Sea Ice Recovering? January 10, 2015.

Last year might have been the hottest year ever recorded by our instruments. Average global temperatures were at least 0.27° C warmer than the average between 1981 and 2010, which was in turn up from the preindustrial norm. Overall, the past 17 years have been very warm, and since 2002 temperatures have been consistently well above the 1981-2010 average. However, that consistency is not clearly reflected in Arctic sea ice trends. In fact, the winter extent of Arctic sea ice has expanded in the last two years, seemingly defying projections of its imminent collapse. More

Climate, Crisis, and Causality in the Bronze Age.December 4, 2014.

In Europe, the “Bronze Age” lasted nearly 2,000 years, from approximately 3200 BCE to roughly 600 BCE. In this period, bronze tools were forged for the first time, revolutionizing how Europeans manipulated their world and competed for resources. The first trading networks connected the continent, as navigational knowledge reached heights that Europeans would not exceed until the fifteenth century. Centralized “palace economies” flourished throughout Europe and the Middle East, in ancient civilizations we remember today: on Minoan Crete, in Mycenaean Greece, in the Mesopotamian conquests of the Hittites and Akkadians, and of course in Egypt. More

A Conversation with Dr. Michael Mann. November 17, 2014.

Dr. Michael Mann is one of the world's best-known climate change scholars. He is the director of the Earth System Science Centre at Pennsylvania State University, where he pioneers innovative methods for reconstructing past climate change. Mann is the author of more than 160 peer-reviewed publications and two books, and he is the founder of the popular climatology blog RealClimate. On Twitter, he is followed by nearly 23,000 people.

For these reasons, we asked Dr. Mann to give an interview that would launch a new "Interviews" section of HistoricalClimatology.com. We are grateful that he took the time to answer our questions. More

For these reasons, we asked Dr. Mann to give an interview that would launch a new "Interviews" section of HistoricalClimatology.com. We are grateful that he took the time to answer our questions. More

How Should we Measure Climate Change? October 11, 2014.

Last month, world leaders met at UN Headquarters in New York City for Climate Summit 2014. As protests raged across the globe, diplomats established the framework for a major climate change agreement next year. The aim will be to limit anthropogenic warming to no more than 2 °C, a threshold established by scientists and policymakers, beyond which climate change is increasingly dangerous and unpredictable. Just days after the 2014 summit, policy expert David Victor and influential astrophysicist Charles Kennel published an article in Nature that called on governments to “ditch the 2 °C warming goal.” More

A scientific expedition to Southeast Greenland. September 9, 2014.

Contributing Author: Benoit S. Lecavalier

The Greenland ice sheet is melting fast, and it contains enough water to raise global sea levels by over seven meters if it were to disappear entirely. However, thousands of years ago the ice sheet was much larger, with a total of 12 metres ice-equivalent sea-level. There are many questions that remain unanswered about how Greenland lost all this ice from past to present. For example: how and where did the Greenland ice sheet lose mass? What climate history resulted in such a drastic change in the ice sheet? This summer, these were the questions that led a multidisciplinary team of geologists, geophysicists, biologists, and biogeologists to Southeast Greenland. We were embarking on an expedition to better understand its climate history, and so resolve part of a much bigger story. More

The Greenland ice sheet is melting fast, and it contains enough water to raise global sea levels by over seven meters if it were to disappear entirely. However, thousands of years ago the ice sheet was much larger, with a total of 12 metres ice-equivalent sea-level. There are many questions that remain unanswered about how Greenland lost all this ice from past to present. For example: how and where did the Greenland ice sheet lose mass? What climate history resulted in such a drastic change in the ice sheet? This summer, these were the questions that led a multidisciplinary team of geologists, geophysicists, biologists, and biogeologists to Southeast Greenland. We were embarking on an expedition to better understand its climate history, and so resolve part of a much bigger story. More

Understanding the culture of climate change. August 4, 2014.

Note: originally posted on The Otter, blog of the Network in Canadian History and Environment.

Like the research that inspired it, this article is a cultural consequence of climate change.

Seven years ago, I was on a bus, reading a book about ancient climates. I looked out the window at a sunset so brilliant, it seemed to ignite Toronto's skyscrapers. I thought of global warming, and wondered: had anyone searched for connections between human history and climate change? Over the next seven years I found out that they had, but that there was still plenty of room for a new perspective. More

Like the research that inspired it, this article is a cultural consequence of climate change.

Seven years ago, I was on a bus, reading a book about ancient climates. I looked out the window at a sunset so brilliant, it seemed to ignite Toronto's skyscrapers. I thought of global warming, and wondered: had anyone searched for connections between human history and climate change? Over the next seven years I found out that they had, but that there was still plenty of room for a new perspective. More

How climate scholars can shape climate policy. July 3, 2014.

In order to keep global warming below 2° C, there is desperate need for urgency in curbing greenhouse gas emissions. However, national and international policymakers have yet to take major action. In the most recent issue of Nature Climate Change, Cambridge University geographer David Christian Rose explains why even the governments that have publicly acknowledged the threat of climate change have been so slow to address it.He then introduces practical ways for researchers to communicate more effectively to policymakers.

Most scholars understandably assume that policy should respond to the weight of evidence. To them, influencing policy is simply a matter of articulating abundant evidence with clarity. However, Rose argues that evidence derived from “scientific rationality” is just one factor among the many that influence policy. More

Most scholars understandably assume that policy should respond to the weight of evidence. To them, influencing policy is simply a matter of articulating abundant evidence with clarity. However, Rose argues that evidence derived from “scientific rationality” is just one factor among the many that influence policy. More

University acquires vast climate history archive. May 25, 2014.

Many articles on this site outline the indispensable role of documentary evidence for testing, refining, and expanding reconstructions of past climates developed using scientific “proxy” sources and computer simulations. Documents that record past weather were written in literate societies, and are only useful in bulk. Hence, reconstructions of ancient climates cannot benefit from documentary refinement, and the same holds true for reconstructions of regions settled by non-literate societies. Nor are all documents equal: written sources that describe processes that respond to weather are useful, but only those are directly refer to weather can be reliably used to reconstruct past climate change and its influence on human activity. More

How does climate change influence warfare? April 28, 2014.

According to the most recent summary for policymakers published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), “climate change can indirectly increase risks of violent conflicts” by exacerbating the socially destabilizing influence of poverty and economic shocks. While the IPCC attaches “medium confidence” to this claim, it is hardly controversial. Similar conclusions were made in the IPCC’s 2007 assessment reports. Since then, several studies have established that warfare is correlated to climatic stress, although their methods ignore social and cultural contexts. Many of the world’s most advanced militaries are now at the forefront of state adaptation to global warming. The American military, for example, is not only curbing its greenhouse emissions, but is also actively preparing for conflict stimulated by future climate change. More

Does climate change cause social crisis? March 25, 2014.

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of generally cooler, and more variable, temperatures that was felt across most of the globe from the thirteenth to the nineteenth centuries. In the wake of a very cold winter in North America, and a very wet winter in Britain, it has been all over the news lately. For example, in the April issue of Foreign Affairs, Deborah Coen evaluates a major new study on the Little Ice Age by fellow historian Geoffrey Parker. In the March 23rd New York Times Sunday Review, Parker presents his “lessons from the Little Ice Age.” Two days earlier, novelist Sarah Dunant offered some of her own lessons from the period for BBC News Magazine.

The focus of each piece is the frigid seventeenth-century nadir of the LIA. For Parker and Dunant, the conclusion is simple: the LIA was disastrous for all who experienced it. Global suffering during a cooler climate foreshadowed what we can expect in a hotter world. If we wish to avoid that fate, we had better act now. More

The focus of each piece is the frigid seventeenth-century nadir of the LIA. For Parker and Dunant, the conclusion is simple: the LIA was disastrous for all who experienced it. Global suffering during a cooler climate foreshadowed what we can expect in a hotter world. If we wish to avoid that fate, we had better act now. More

Major study interprets recent climate in light of past. February 20, 2014.

Last year the World Meteorological Organization released an important summary report on the world’s climate and how we make sense of it. The World’s Climate: 2001-2010 was unfortunately overshadowed by the publication of the Fifth Summary for Policymakers written by the UN’sIntergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. However, its conclusions are continuing to trickle through blogs and media outlets, as they shed new light on the past, present, and future of the world’s climate. Some of these conclusions will be familiar to scientists, but they are worth repeating for scholars of different disciplines, policymakers, and the general public. More

Understanding Toronto's wild weather of 2013. January 15, 2014.

Initially published on ActiveHistory.ca

In Toronto, 2013 was a year of storms. The media storm kindled by the mayor’s chicanery was twice interrupted by meteorological storms that threatened lives and property on an unprecedented scale. On July 8th more than 100 mm of rain inundated the city in a matter of hours, triggering flash floods that caused more than $1 billion in property damage. Three days before Christmas, winter storm Gemini unleashed more freezing rain than was ever recorded in Toronto. Some 300,000 customers – representing perhaps one million people – lost power as temperatures plummeted below -10° C. This time the city’s infrastructure succumbed to the force of frozen water, and those desperate for heat too often turned to candles, generators, and other sources of deadly carbon monoxide. More

In Toronto, 2013 was a year of storms. The media storm kindled by the mayor’s chicanery was twice interrupted by meteorological storms that threatened lives and property on an unprecedented scale. On July 8th more than 100 mm of rain inundated the city in a matter of hours, triggering flash floods that caused more than $1 billion in property damage. Three days before Christmas, winter storm Gemini unleashed more freezing rain than was ever recorded in Toronto. Some 300,000 customers – representing perhaps one million people – lost power as temperatures plummeted below -10° C. This time the city’s infrastructure succumbed to the force of frozen water, and those desperate for heat too often turned to candles, generators, and other sources of deadly carbon monoxide. More

Climate history is under attack in Canada. January 6, 2014.

In 2012 the Canadian government infamously announced changes toLibrary and Archives Canada (LAC) that made it much harder for researchers to access their country’s documentary heritage. The LAC’s mandate was transformed: rather than acquiring and maintaining a “comprehensive” collection, it now aimed merely to gather a “representative” assembly of Canadian documents. Funding was slashed, employees were laid off, new acquisitions were paused, documents were sold to private bidders, and resources were decentralized across Canada.

In the last month, interviews with scientists by The Tyee have revealed how the conservative regime’s attitude towards the environment meant that environmental archives suffered the most. More

In the last month, interviews with scientists by The Tyee have revealed how the conservative regime’s attitude towards the environment meant that environmental archives suffered the most. More

Study applies social learning theory to climate change research. December 20, 2013.

This is an educational website. Most of its articles have described the insights and methodologies of scientists, humanists and ordinary people who study climates past, present and future. Many conclude with a simple warning: to effectively address anthropogenic global warming, we need more inclusive ways to transform learning into practice. However, very few of these articles have explored how that can be done. With good reason: interdisciplinary work is never easy, and even harder is research that incorporates diverse perspectives from those closest to the effects of climate change.

A new article in by Patti Kristjanson, Blane Harvey, Marissa van Epp and Philip Thornton in the journal Nature Climate Change introduces “social learning” approaches as a way of integrating a wide range of perspectives into climate change research. More

A new article in by Patti Kristjanson, Blane Harvey, Marissa van Epp and Philip Thornton in the journal Nature Climate Change introduces “social learning” approaches as a way of integrating a wide range of perspectives into climate change research. More

Did the Little Ice Age really exist? November 24, 2013.

For nearly a century, interdisciplinary scholars have gradually reconstructed the existence of a so-called “Little Ice Age.” Their research is ongoing, but most now believe that average global temperatures declined by about one degree Celsius between the thirteenth and the twentieth centuries. The extent, meteorological consequences, and timetable of cooling varied from region to region, but sorting through these statistical complexities still yields an unmistakable downward trend in planetary temperatures.

Or does it? Economic historians Morgan Kelly and Cormac Ó Gráda of University College Dublin challenge the existence of a Little Ice Age (LIA) in a special issue of The Journal of Interdisciplinary History (JIH). Kelly and Ó Gráda examine recent reconstructions of European winter and summer temperatures from the medieval period to the twentieth century, but find “no statistical evidence of any major breaks, trends or cycles in European weather of the sort that one could associate with an LIA.” More

Or does it? Economic historians Morgan Kelly and Cormac Ó Gráda of University College Dublin challenge the existence of a Little Ice Age (LIA) in a special issue of The Journal of Interdisciplinary History (JIH). Kelly and Ó Gráda examine recent reconstructions of European winter and summer temperatures from the medieval period to the twentieth century, but find “no statistical evidence of any major breaks, trends or cycles in European weather of the sort that one could associate with an LIA.” More

Study provides new context for recent Arctic warming. October 27, 2013.

At the beginning of the Holocene roughly 10,000 years ago, 9% more sunlight reached the Northern Hemisphere than today. Very gradually, less solar radiation warmed the far north, and regional temperatures started a lengthy decline. However, at the turn of the twentieth century that trend reversed sharply, and warming has accelerated since the 1970s. Recently published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, a University of Colorado Boulder study by lead author Gifford Miller applies radiocarbon dating to new sources in a quest for more accurate reconstructions of these climatic shifts.

Gifford and his co-authors travelled to Baffin Island, the largest island in the Canadian Arctic. The massive ice caps on the highlands of Baffin Island are frozen to relatively flat terrain, which prevents them from flowing and preserves the ancient landscape in which they formed. Changes along the fringes of these ice caps therefore reflect changes in temperature rather than other environmental conditions. The researchers collected dead tundra plants within one meter of four ice caps that are now receding by two to three meters a year. More

Gifford and his co-authors travelled to Baffin Island, the largest island in the Canadian Arctic. The massive ice caps on the highlands of Baffin Island are frozen to relatively flat terrain, which prevents them from flowing and preserves the ancient landscape in which they formed. Changes along the fringes of these ice caps therefore reflect changes in temperature rather than other environmental conditions. The researchers collected dead tundra plants within one meter of four ice caps that are now receding by two to three meters a year. More

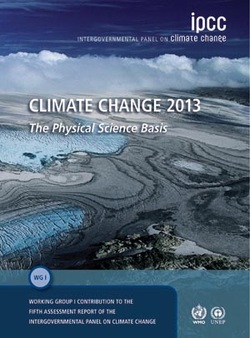

Understanding the Fifth IPCC Assessment Report. September 27, 2013.

Established in 1988 by the UN and the World Meteorological Organization, theIntergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is a scientific body that periodically summarizes the scholarly understanding of the world’s climate. In 2007, the panel’s fourth assessment report outlined in stark terms the likelihood of anthropogenic global warming. Since then, severe storms and drought have ravaged North America, Australia and Africa, yet unusually wet, cold conditions have accompanied some European winters. Through it all carbon emissions have continued to rise, now driven largely by developing nations. Today, the IPCC’s highly anticipated summary for policymakers was finally released, in lieu of its fifth assessment report that will be published later this year. In this article, I explore this landmark report and the responses it has inspired from the perspective of a climate historian.

Initially, the most striking aspect of the IPCC’s new summary for policymakers was not its content but the media reaction. The banner at CNN is currently: “A town that’s melting.” Its subheading: “climate change already happening in Alaska town.” Additional titles announce: “climate change: it’s us,” and “Miama’s rising water,”while an opinion calls for “common sense.” Not surprisingly, among major news networks the BBC has provided the most informative analysis of the IPCC’s report, and its banner, while not as large as CNN’s, nevertheless reads: “UN ‘95% sure’ humans cause warming.” Of course, the Fox News headline is in substantially smaller font, and its conclusion is characteristically fair and balanced: “Hockey Schtick: UN report ignores global warming pause.” Worse still is coverage given by the Times of India, which features only a link in diminutive font buried at the bottom of its website. More

Initially, the most striking aspect of the IPCC’s new summary for policymakers was not its content but the media reaction. The banner at CNN is currently: “A town that’s melting.” Its subheading: “climate change already happening in Alaska town.” Additional titles announce: “climate change: it’s us,” and “Miama’s rising water,”while an opinion calls for “common sense.” Not surprisingly, among major news networks the BBC has provided the most informative analysis of the IPCC’s report, and its banner, while not as large as CNN’s, nevertheless reads: “UN ‘95% sure’ humans cause warming.” Of course, the Fox News headline is in substantially smaller font, and its conclusion is characteristically fair and balanced: “Hockey Schtick: UN report ignores global warming pause.” Worse still is coverage given by the Times of India, which features only a link in diminutive font buried at the bottom of its website. More

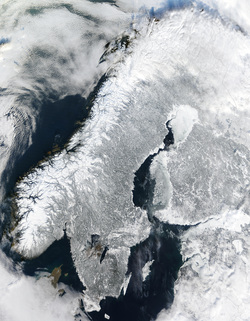

Discussing deglaciation in Arctic Norway. September 17, 2013.

Contributing Author: Benoit S. Lecavalier.

August 18th, 2013 marked the start of a two week long workshop called the Advanced Climate Dynamics Course (ACDC). The venue was located in a former fishing village in the Vesterålen islands of Arctic Norway, a little place called Nyksund with a population of slightly over a dozen permanent residents. We were there for more than just hiking through the great outdoors, eating the local food, and performing local outreach. We were there to discuss what many call small talk: the climate. Organized by European and North American Universities, this event attracted internationally renowned researchers and graduate students, gathered there to discuss the climate dynamics of the last deglaciation. More

August 18th, 2013 marked the start of a two week long workshop called the Advanced Climate Dynamics Course (ACDC). The venue was located in a former fishing village in the Vesterålen islands of Arctic Norway, a little place called Nyksund with a population of slightly over a dozen permanent residents. We were there for more than just hiking through the great outdoors, eating the local food, and performing local outreach. We were there to discuss what many call small talk: the climate. Organized by European and North American Universities, this event attracted internationally renowned researchers and graduate students, gathered there to discuss the climate dynamics of the last deglaciation. More

New directions in climate history at the ESEH. September 4, 2013.

A week ago I returned from what was, surprisingly, my first trip to Germany. This year the European Society for Environmental History convened its biannual conference in Munich, a city I’ll remember for its beautiful architecture, sensible public transit and delicious beer. No fewer than fifteen climate history panels were part of the conference, and despite my best attempts I couldn't attend them all. Still, I decided to share some of what I learned (or remembered) while listening to papers that were good enough to keep me from exploring Munich. Note that for the purposes of this little article, the terms “climate history” and “historical climatology” are synonymous. More

Study Reconstructs African Climate History. July 30, 2013.

Earth’s climate has never been stable. Owing to the rising concentration of greenhouse gases in our atmosphere, it is warming now. However, other influences have caused it to fluctuate in the past, and to gain insight into the future of our climate it is critical that we understand its history. Efforts to reconstruct that past have had a western bias, owing in part to the substantial documentary legacy of European societies and their colonial descendants. Moreover, the modern interdisciplinary pursuit of historical climatology first emerged in Europe, and efforts to understand the European climate have received impressive government funding.

In recent years scholars across the globe have begun to address that imbalance. As the consequences of global warming grow increasingly obvious, international programs like the Past Global Changes (PAGES)project have gathered interdisciplinary researchers into teams dedicated to particular regions, epochs or methodologies, in the quest for a comprehensive picture of past climatic variability. A new article in the journal The Holocene presents the results of one PAGES initiative, which exhumed sources from the full breadth of Africa to incorporate the continent within the global climatic record. More

In recent years scholars across the globe have begun to address that imbalance. As the consequences of global warming grow increasingly obvious, international programs like the Past Global Changes (PAGES)project have gathered interdisciplinary researchers into teams dedicated to particular regions, epochs or methodologies, in the quest for a comprehensive picture of past climatic variability. A new article in the journal The Holocene presents the results of one PAGES initiative, which exhumed sources from the full breadth of Africa to incorporate the continent within the global climatic record. More

Study: predator-prey relationship affects carbon cycle. June 18, 2013.

When most people conceive of the causes – or “forcing” – behind climate change, they think of volcanoes, solar radiation and, increasingly, human industry. Those who are more informed might also imagine forests, or perhaps the noxious emissions of 1.3 billion cows. However, pioneering research has increasingly revealed that biological activity on small scales, replicated in countless interactions across the planet, can yield equally substantial influences.

Carbon is, of course, both a fundamental component of life and a major contributor to global warming. Countries across the world have invested billions in storing surplus carbon, yet lucky for us plants and animals also absorb carbon in vast quantities. More

Carbon is, of course, both a fundamental component of life and a major contributor to global warming. Countries across the world have invested billions in storing surplus carbon, yet lucky for us plants and animals also absorb carbon in vast quantities. More

Studies: modern glacier retreat unprecedented. May 19, 2013.

Nearly 70% of the world’s freshwater – over 24 million cubic kilometers - is frozen, locked within ice caps, permanent snow, or glaciers. That ice holds less than 2% of Earth’s total reservoir of water, yet sea levels would rise by hundreds of feet if it all melted. A complete thaw is not on the horizon, but even sea level rises of several feet would render many coastal cities uninhabitable. Hence, although glaciers only constitute 1% of the world’s total land ice, we desperately need studies that measure their response to global warming.

Recent research by lead author Alex Gardner of Clark University revealed that glaciers lost an average of 260 billion metric tons of ice annually between 2003 and 2009. That alarming conclusion suggests that, during the study period, glaciers contributed as much to sea level rises as the Arctic and Antarctic ice sheets combined. While this information is valuable, it requires the context provided by research into the deeper past, without which the recent retreat of glaciers can be dismissed as just another quirk of short-term variations in weather. More

Recent research by lead author Alex Gardner of Clark University revealed that glaciers lost an average of 260 billion metric tons of ice annually between 2003 and 2009. That alarming conclusion suggests that, during the study period, glaciers contributed as much to sea level rises as the Arctic and Antarctic ice sheets combined. While this information is valuable, it requires the context provided by research into the deeper past, without which the recent retreat of glaciers can be dismissed as just another quirk of short-term variations in weather. More

New methods link atmospheric CO2 to climate change. April 27, 2013.

When researchers study past climates to better understand modern warming, they often seek “climate analogues,” times when climatic variables resembled those we face today. According to celebrated climatologist André Berger, problems emerge when we start asking which variables render climates analogous. Is it temperature? Sea level? Patterns of vegetation? Forcing influences? Unfortunately for climatologists and climate historians, superficially similar climates can emerge from very different stimuli, and they can be expressed in very different ways in different places.

Almost 34 million years ago, the world’s climate changed and, as it did, ice sheets extended across the Antarctic. Ice reflects sunlight better than water, and the dramatic expansion of Antarctic ice stimulated a long-term decline in ocean temperatures. Despite recent warming, the colder climate that emerged from this Eocene–Oligocene transition actually resembles our own. We live in an icy – if thawing – climate, and global warming is alarming not because it imperils life on Earth, but because it threatens how modern life has adjusted to regional environments. Just as polar bears need ice to hunt, our civilization requires moderate, predictable temperatures for the agricultural monocultures that sustain it. More

Almost 34 million years ago, the world’s climate changed and, as it did, ice sheets extended across the Antarctic. Ice reflects sunlight better than water, and the dramatic expansion of Antarctic ice stimulated a long-term decline in ocean temperatures. Despite recent warming, the colder climate that emerged from this Eocene–Oligocene transition actually resembles our own. We live in an icy – if thawing – climate, and global warming is alarming not because it imperils life on Earth, but because it threatens how modern life has adjusted to regional environments. Just as polar bears need ice to hunt, our civilization requires moderate, predictable temperatures for the agricultural monocultures that sustain it. More

New studies explore social context of natural disasters. April 9, 2013.

The journal Environment and History has recently published a special issue devoted to historic floods in medieval and early modern Europe. In an editorial introduction, historian James Galloway explains that studies examining environmental disasters have multiplied since the 1980s in the kind of history that seeks connections between the human and non-human worlds. Increasingly, natural disasters are not perceived as unavoidable transgressions on society – “acts of God” - but, instead, as a product of a particular society. Natural catastrophes are, in fact, “social phenomena” located at the intersection of a society’s unique pattern of vulnerability and resilience in its relationship with the nonhuman world. The papers in the latest issue of Environment and History reconstruct past natural disasters, consider the interactions between them and past societies, and measure the relevance of such research in an era particularly prone to environmental catastrophe.

Historical climatologist Christian Rohr begins the issue with an innovative paper that explores tangled relationships between floods and urban economies on the upper Danube between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries. Using an impressive variety of documentary evidence, Rohr reveals that medieval and early modern city communities understood the perpetual risk of flooding. In fact, many within these communities actually benefited from it: carpenters, for example, gained a sizable share of their annual income from the repair of flood damage. More

Historical climatologist Christian Rohr begins the issue with an innovative paper that explores tangled relationships between floods and urban economies on the upper Danube between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries. Using an impressive variety of documentary evidence, Rohr reveals that medieval and early modern city communities understood the perpetual risk of flooding. In fact, many within these communities actually benefited from it: carpenters, for example, gained a sizable share of their annual income from the repair of flood damage. More

Study: volcanic eruptions diminished recent warming. March 3, 2013.

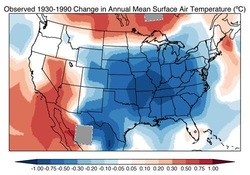

Average global temperatures fluctuate in response to many different influences, and while some of these "forcings" are now affected by humans, others are shaped entirely by natural causes. Articles on this website have considered whether sulfur released into the atmosphere by volcanic eruptions stimulated the prolonged cooling of the so-called Little Ice Age in the centuries before 1850. Deposited in the stratosphere, volcanic sulfur dioxide interacts with other chemicals to form sulfuric acid and water, which in turn reflects solar radiation. Other articles on the site have introduced research revealing that the reflective properties of man made aerosol pollution in the twentieth century likely sheltered swaths of North America and, later, parts of China from the influence of global warming. More

Debate tests accuracy of tree ring data. February 6, 2013.

For those interested in climates past and present, trees do more than absorb carbon dioxide. Seasonal changes in cellular growth near the bark of a tree leave rings buried in its wood. The size of those records is tied to the growth of the tree; a good year will imprint a thick ring, while hard times leave mere slivers. Anyone who's ever owned a plant will understand that most trees need abundant sun, moderate temperatures and sufficient water. Of course, gardeners are aware that different plants - from weeds to trees - respond to different conditions. By researching the peculiar tastes of various tree species climatologists can use tree trunks to reconstruct yearly fluctuations in temperature and precipitation, sometimes over hundreds of years. More

Climate change research: now for historians. January 13, 2013.

Most scholars study something important to their societies. The walls of the ivory tower are, in fact, quite porous. It's no surprise that the genre of history that deals with environmental issues - environmental history - grew out of the debates surrounding the use of DDT. No surprise, either, that academics within disciplines from anthropology to economics are increasingly considering the influence of climate change just as the effects of global warming are becoming painfully obvious. Now more than ever, research into past climates is not just for scientists.

If environmental history grew steadily in the decades since its conception, so too did its semi-autonomous, interdisciplinary cousin: climate history, or historical climatology. This site regularly describes some of the more interesting work published by historical climatologists, before considering how it can reframe today's environmental issues. More

If environmental history grew steadily in the decades since its conception, so too did its semi-autonomous, interdisciplinary cousin: climate history, or historical climatology. This site regularly describes some of the more interesting work published by historical climatologists, before considering how it can reframe today's environmental issues. More

Climate change and ice cover in one Arctic lake. December 16, 2012.

Average air temperatures have risen across much of the globe in recent decades, nowhere more quickly than in the Arctic. However, the consequences of rapid warming for the environmental conditions that shape life in the Arctic remain poorly understood. A new article published in the journal Climatic Change by an international team of scholars under lead author Ruibo Lei uses 44 years of ice data fromLake Kilpisjärvi, in the Northwestern fringe of Finland, as a case study to improve our understanding of recent shifts in Arctic ice cover. Because the workings of lake ice can be easily related to large-scale atmospheric changes, past ice records can shed new light on local and regional climate change. Extensive regional ice monitoring dates back to 1964, and the remoteness of the lake ensures that human influences other than anthropogenic change likely had little to no impact on the ice data. More

Study: drought triggered Mayan collapse. November 9, 2012.

For seven centuries the Classic Maya dominated central America, developing a unique society that in its complexity rivaled the greatest civilizations of contemporary Asia or Europe. For over three decadessome scholars attempted to link the gradual collapse of Mayan population centers between 800 and 1000 CE to sustained drought influenced by a change in the regional climate. However, their conclusions remained controversial, in part because climatic reconstructions compiled usingpaleoclimatic records were not yet sufficiently precise. More recent articles supported the drought hypothesis for the collapse of Mayan Civilization, but environmental circumstances like human-caused deforestation complicated attempts to piece together what happened near the most important cities of Mayan antiquity. More

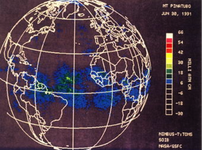

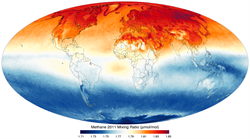

Study: methane emissions linked to human activity for millennia. October 6, 2012.

Methane in the upper troposphere, 2011.

Using new data from the NEEM and EUROCORE ice core drilling programs, researchers from the Niels Bohr Institute have published a study in the journal Nature that reconstructs how different natural and anthropogenic activities contributed to methane emissions over the last two millennia. An important but frequently ignored greenhouse gas, methane is released into the troposphere from three sources: biogenic (wetlands or rice paddies, for instance), geological (for example, mud volcanoes) or pyrogenic (including biofuel or coal burning). Different methane sources have different isotopic signatures, meaning that scientists can use ice cores to trace how and why methane rose and fell over time. More

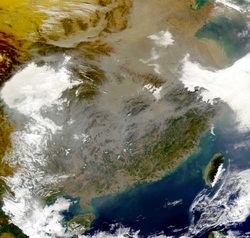

Pollution cooling summers in one part of China. September 30, 2012.