Does tree ring data reflect global cooling? July 9, 2012.

Credit: Institute of Geography, JGU

In a study published in the journal Nature Climate Change and sure to be widely misinterpreted, a team under lead author Jan Esper has used new dendrochronological (tree ring) data from sub-fossil pine trees to reconstruct Finnish temperatures back to 138 BC. The results faithfully record past climatic fluctuations from the Roman warm period to the Little Ice Age, but they also seem to reflect a surprising trend: the cooling of European temperatures by 0.31 degrees Celsius for each of the last two millennia prior to the onset of anthropogenic climate change. Tree ring data is derived from measurements of the distance between growth rings in the trunk of a tree. It not only reflects variability in temperature but also precipitation, with some trees responding more strongly to a particular meteorological variable than others. Researchers must take this into account, and since the 1970s historical climatologists have carefully reconstructed Scandinavian temperatures using dendrochronological data. However, the new study appears to reveal a general cooling trend missing from previous records, with results now fitting coupled general circulation models. Esper and his co-authors conclude that cooling over the past two millennia was driven by a gradual reduction in solar radiation driven by changes in Earth's orbit around the sun. According to Esper, these findings are "significant with regard to climate policy, as they will influence the way today's climate changes are seen in the context of historical warm periods." Sure, but how?

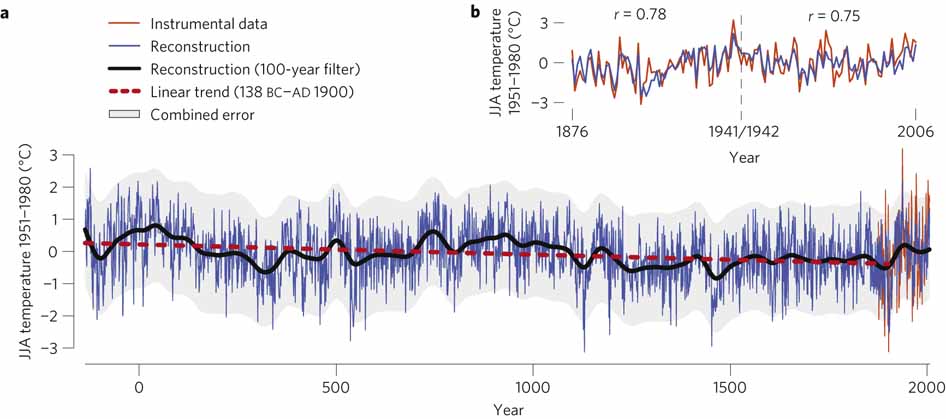

This graph was published with the article, reflecting summer temperatures:

This graph was published with the article, reflecting summer temperatures:

The line denoting the "linear trend" in both graphs appears to conclude with the final cold phase of the Little Ice Age, as Europe experienced "years without summer," and as a result the line slopes downwards. This decision is never explained in the study: why not end the line at 1900, for example? The results might then have reflected a general warming trend not as easily explained by orbital changes. Alternatively, why not start around 100 BC, when temperatures were cooler? Again, a warming trend would have emerged. Also worth noting: these are summer temperatures, compiled with only one kind of source, reflecting changes in one corner of Europe. What kind of conclusions can really be drawn from such data? Multi-season reconstructions compiled with multiple paleoclimatological sources and historical (documentary) evidence are available for many regions in Europe and record climatic fluctuations over the past millennium, but different regions - China, for example - have different climatic histories.

Ultimately, this study, which is receiving significant media attention, represents a valuable contribution to the reconstruction of past European temperatures. Whether it demonstrates a long-term Scandinavian, much less a European or even global cooling trend remains uncertain. Also uncertain: would the rapid and accelerating pace of global warming today seem more alarming and more obviously anthropogenic in the face of previously experienced long-term cooling trends, or would it seem less worrisome because current temperatures are similar to those experienced at the height of the Roman Empire? There are no easy answers when we consider how scholars interpret quantitative data, and how the public, in turn, reacts to academic conclusions filtered through media outlets.

Ultimately, this study, which is receiving significant media attention, represents a valuable contribution to the reconstruction of past European temperatures. Whether it demonstrates a long-term Scandinavian, much less a European or even global cooling trend remains uncertain. Also uncertain: would the rapid and accelerating pace of global warming today seem more alarming and more obviously anthropogenic in the face of previously experienced long-term cooling trends, or would it seem less worrisome because current temperatures are similar to those experienced at the height of the Roman Empire? There are no easy answers when we consider how scholars interpret quantitative data, and how the public, in turn, reacts to academic conclusions filtered through media outlets.