The Climatological Database for the World's Oceans (CLIWOC) represents the culmination of a major project funded by the European Union, and pursued by a large team of researchers in organizations and universities around the world.

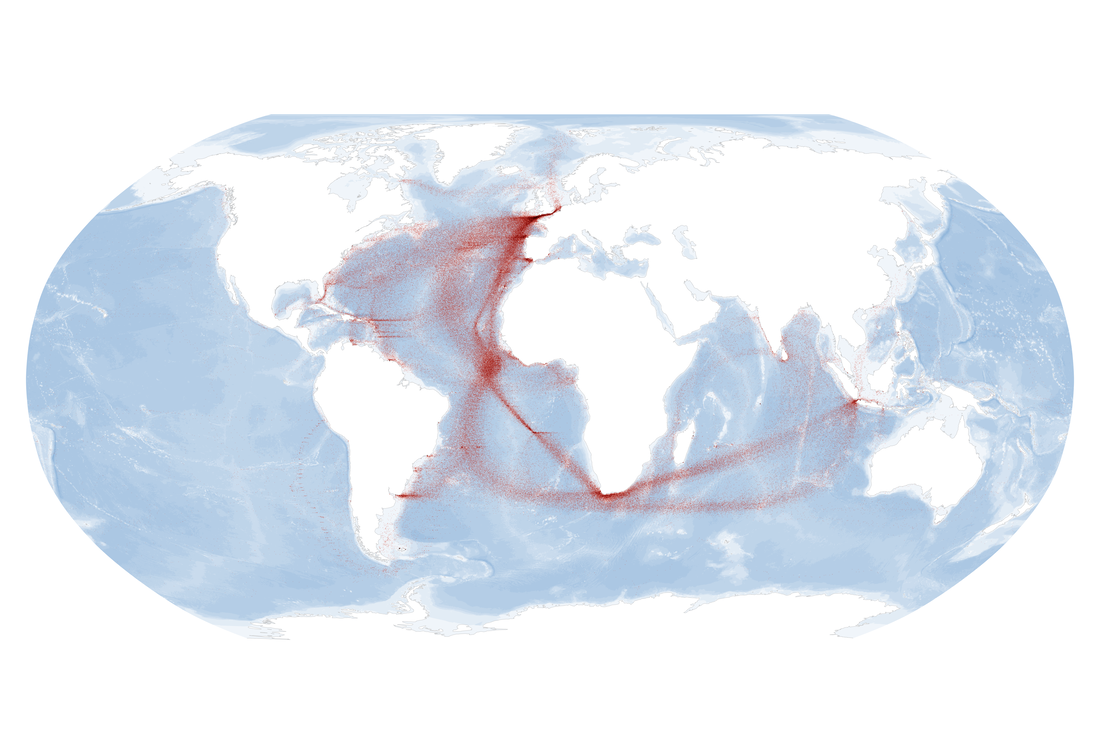

The database consists of 287,114 logbooks written aboard Dutch, English, French, and Spanish sailing ships. The vast majority of these logbooks date from between 1750 and 1850, yet four ship logbooks were incorporated that predate 1750. These were centuries of European imperial expansion, and so the logbooks record the activities of sailors - both civilian and military - in oceans that span the entire globe.

European sailors started writing daily logs in the sixteenth century, as they began to regularly leave familiar shores. One reason was that the leaders of increasingly bureaucratized admiralties and merchant companies wished to evaluate the performance of their officers.

A more important reason had to do with the limits of contemporary navigation. From the mid-seventeenth century, sailors could determine latitude with reasonable accuracy even while far from coastal landmarks. Yet until the eighteenth-century invention, and the widespread nineteenth-century implementation, of the marine chronometer, they could only estimate longitude using “dead reckoning.”

Dead reckoning was a technique that required knowledge of three essential variables: a ship’s speed, measured by log line; its course, determined by compass; and any drift by the ship from its course. That last variable responded primarily to the direction and velocity of the wind.

To have even a rough sense of where they were, sailors needed to obsessively keep track of the wind. Most ship logbooks therefore abound with reliable, detailed, and almost unbroken weather observations that sailors wrote down whenever the wind changed. That makes them priceless sources for graphing and mapping past climate changes, particularly as they unfolded at sea - where researchers often have fragmentary or low resolution evidence. Moreover, they are unique - and uniquely underused - sources for connecting weather events and climate trends to human history.

In the CLIWOC project, researchers quantified all of this information and entered it into what was originally a Microsoft Access database. They made the information available online for free, yet over time its formatting became increasingly obsolete. To use the database, researchers had to download and often pay for an outdated program that few knew how to use.

In late 2018, HistoricalClimatology.com Director Dagomar Degroot - who has used CLIWOC extensively - presented new findings from the database at a Past Global Changes (PAGES) workshop. Mapper and programmer Steven Ottens saw an image of the presentation on social media and realized that he could make CLIWOC much more accessible than it had been.

Thanks to Steven, the entire database is now hosted in accessible, commonly used formats on HistoricalClimatology.com.

The database consists of 287,114 logbooks written aboard Dutch, English, French, and Spanish sailing ships. The vast majority of these logbooks date from between 1750 and 1850, yet four ship logbooks were incorporated that predate 1750. These were centuries of European imperial expansion, and so the logbooks record the activities of sailors - both civilian and military - in oceans that span the entire globe.

European sailors started writing daily logs in the sixteenth century, as they began to regularly leave familiar shores. One reason was that the leaders of increasingly bureaucratized admiralties and merchant companies wished to evaluate the performance of their officers.

A more important reason had to do with the limits of contemporary navigation. From the mid-seventeenth century, sailors could determine latitude with reasonable accuracy even while far from coastal landmarks. Yet until the eighteenth-century invention, and the widespread nineteenth-century implementation, of the marine chronometer, they could only estimate longitude using “dead reckoning.”

Dead reckoning was a technique that required knowledge of three essential variables: a ship’s speed, measured by log line; its course, determined by compass; and any drift by the ship from its course. That last variable responded primarily to the direction and velocity of the wind.

To have even a rough sense of where they were, sailors needed to obsessively keep track of the wind. Most ship logbooks therefore abound with reliable, detailed, and almost unbroken weather observations that sailors wrote down whenever the wind changed. That makes them priceless sources for graphing and mapping past climate changes, particularly as they unfolded at sea - where researchers often have fragmentary or low resolution evidence. Moreover, they are unique - and uniquely underused - sources for connecting weather events and climate trends to human history.

In the CLIWOC project, researchers quantified all of this information and entered it into what was originally a Microsoft Access database. They made the information available online for free, yet over time its formatting became increasingly obsolete. To use the database, researchers had to download and often pay for an outdated program that few knew how to use.

In late 2018, HistoricalClimatology.com Director Dagomar Degroot - who has used CLIWOC extensively - presented new findings from the database at a Past Global Changes (PAGES) workshop. Mapper and programmer Steven Ottens saw an image of the presentation on social media and realized that he could make CLIWOC much more accessible than it had been.

Thanks to Steven, the entire database is now hosted in accessible, commonly used formats on HistoricalClimatology.com.

Download as an Open Office Spreadsheet

Download as a Tab-Delimited Text File

Download as a Geopackage

You can read more about how the database was originally coded, and has now been reformatted, at Steven's website. This is essential reading if you'd like to use the database for climate history research.

To interpret nautical terms in the database, you will likely need to use a dictionary created as part of the CLIWOC project.

Finally, for examples of how the database may be used in histories that connect past climate change to human affairs, see Chapter 2 of Dagomar Degroot, The Frigid Golden Age: Climate Change, the Little Ice Age, and the Dutch Republic, 1560-1720. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

To interpret nautical terms in the database, you will likely need to use a dictionary created as part of the CLIWOC project.

Finally, for examples of how the database may be used in histories that connect past climate change to human affairs, see Chapter 2 of Dagomar Degroot, The Frigid Golden Age: Climate Change, the Little Ice Age, and the Dutch Republic, 1560-1720. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018.