A Frigid Golden Age: Can the Society of Rembrandt and Vermeer Teach Us About Global Warming?2/27/2018

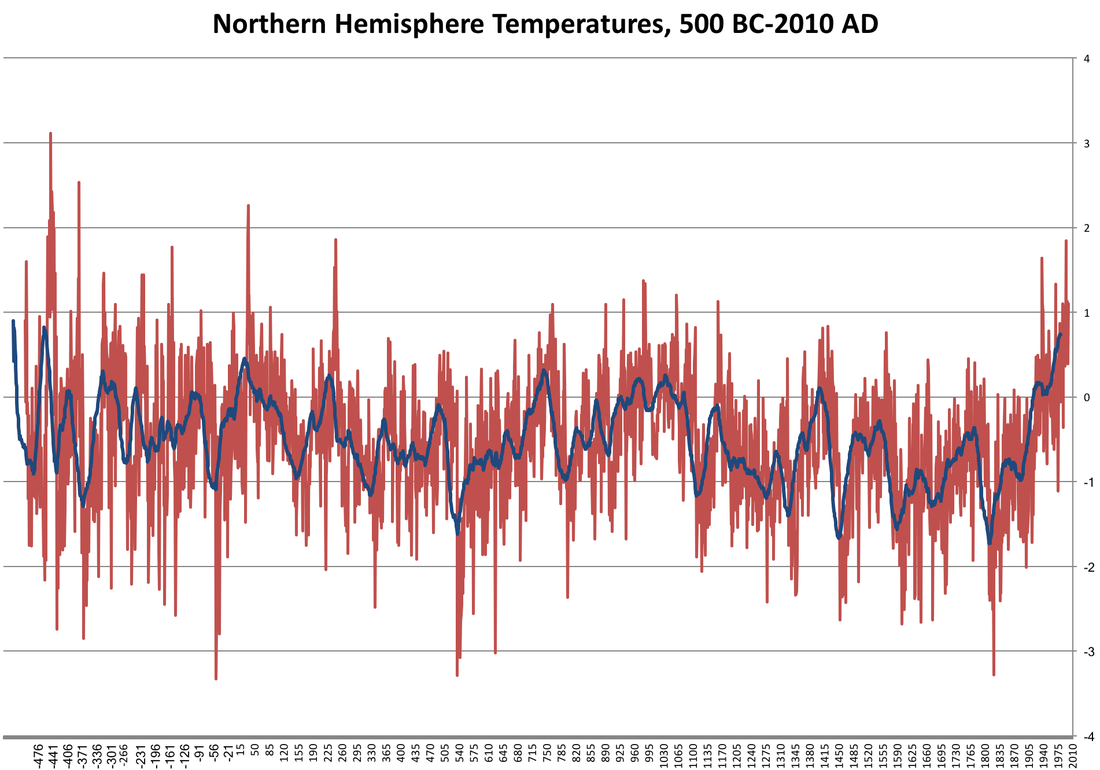

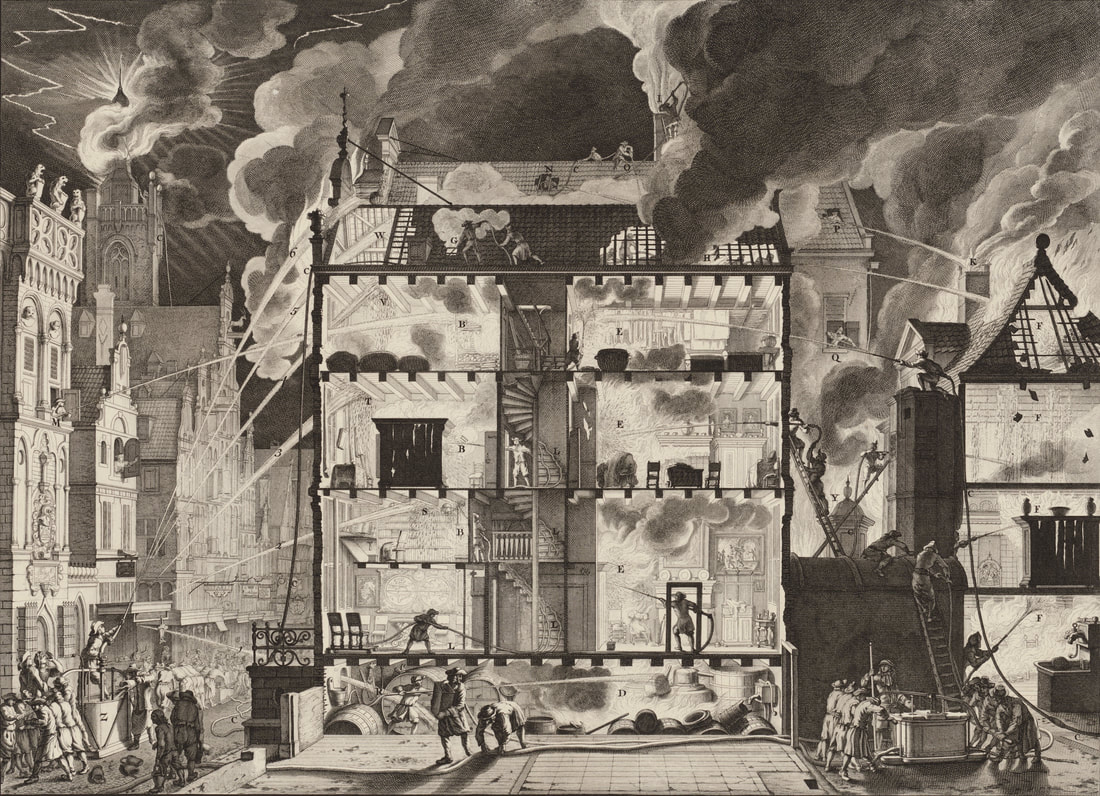

Dr. Dagomar Degroot, Georgetown University Earth’s climate is changing with terrifying speed. Humanity has added several hundred billion tons of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, strengthening a greenhouse effect that has now warmed the planet by roughly one degree Celsius. The scale, speed, and causes of today’s global warming have no precedent, but of course natural forces have always changed Earth’s climate. We now know that these changes were big enough to shape the fates of past societies. Most confronted disaster, but a few seemed to prosper in spite of – and in some cases because of – climate changes. Perhaps the most successful of all emerged in the coastal fringes of the present-day Netherlands. It has left us with lessons that may offer new perspectives on our fate in a warmer world. To contextualize present-day warming, paleoclimatologists have scoured the globe for signs of past climate change. They have found layers buried deep in glacial ice and cave stalagmites, sediments embedded in lakebeds and ocean floors, and rings wound around tree trunks and stony corals. All bear silent testament to ancient weather. Together, they reveal that, sometime in the thirteenth century, Earth’s climate started cooling. Huge volcanic eruptions lofted dust high into the stratosphere that blocked incoming sunlight. The Sun itself slipped into a dormant phase, sending less energy to the Earth. A long-running shift in Earth’s axial tilt gradually reduced the amount of solar energy that reached the northern hemisphere. Sea ice expanded, wind patterns changed, and ocean currents altered their flow. Patterns of precipitation fluctuated dramatically, bringing torrential rains to some places, and unprecedented droughts to others. A long “Little Ice Age” had begun.  A tree ring reconstruction of average summer temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere over the past 2,500 years (red), with a thirty-year moving average (blue). The baseline (“0”) is the late twentieth-century average. Temperatures in the seventeenth century were cold but erratic. Developed from M. Sigl et al., “Timing and Climate Forcing of Volcanic Eruptions for the Past 2,500 Years,” Nature 523 (2015): 545. In the closing decades of the sixteenth century, this Little Ice Age reached its chilliest point across much of the northern hemisphere. By then, the world had cooled by nearly one degree Celsius, relative to average temperatures in the twentieth century. In many places, weather had also grown more volatile and less predictable from year to year, season to season. Despite its name, the Little Ice Age involved more than constant cooling. Historians, historical geographers, and archaeologists have argued that the onset of the coldest and most erratic phase of the Little Ice Age could not have come at a worse time. For centuries, populations in the greatest empires of the day had steadily increased. By the sixteenth century, millions depended on crops stubbornly cultivated in arid, unproductive farmland. When falling temperatures shortened growing seasons, when monsoons failed, or when storms flooded fields, harvests in these regions failed again and again. Many farmers responded by swapping crops that prefer warm, stable weather for those that cope better with cold, volatile conditions. Some diversified their fields. Yet often there was just no dealing with droughts, torrential rains, or cold snaps that lasted for longer than a year or two. Famine and then starvation spread from the plains of the Aztec Empire to the woodlands of the Mutapa Kingdom, from the steppes of the Grand Duchy of Moscow to the rice fields of the Ming Dynasty. The worst was yet to come. Temperature and precipitation extremes sickened plants and animals alike, compounding food shortages. As temperatures dropped, farmers huddled in huts with their ailing livestock. In those conditions, diseases spread easily from animals to people. Malnourished human bodies, meanwhile, have weak immune systems, which makes them easy prey for bacteria and viruses. Changing weather patterns also altered the range of insects that carried disease pathogens, bringing new and deadly ailments to the previously unexposed. In empire after empire, millions fled from the famine-stricken countryside, unwittingly infected by diseases that they carried to cities. Where famine lingered, epidemic outbreaks often followed. In one empire after another, the sick and starving blamed governments for their misery. They were usually right. Few governments responded constructively to the crises they faced, and most made them worse by, for example, increasing taxes or embarking on wars. The coldest stretch of the Little Ice Age therefore coincided with an unprecedented surge of revolts and civil wars. Rebel and state armies alike conscripted farm laborers from the already overburdened countryside, imposed new demands on marginal farmland, and joined refugees in spreading disease. In the end, millions died. Yet remarkably, inhabitants of the Dutch Republic – the precursor state to today’s Netherlands – enjoyed a Golden Age that perfectly coincided with the chilliest century of the Little Ice Age. Somehow, a country with about as many people as Providence, Rhode Island emerged as a European great power, with a navy that went from victory to victory, an army that held the mighty Spanish Empire at bay, and a commercial fleet that dwarfed all others. Today, the art of Rembrandt and Vermeer – painted in the coldest years of the Little Ice Age – gives a distant echo of the energy and prosperity of those incredible times. The Dutch Republic was something of an oddball in the seventeenth-century world. The overwhelming majority in most societies toiled in rural fields, growing crops for local markets. Many Dutch farmers, by contrast, cultivated cash crops for distant consumers. The republic therefore depended on a steady flow of grain imports from the rich and diverse farmland along the Baltic Sea. Over time, a growing share of Dutch citizens worked in commercial interests and industries with headquarters in or near port cities that would have been underwater, were it not for an extensive network of dikes and sluices. Urbanization rates were soon higher in the republic than they were just about anywhere else. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of sailors plied Dutch trades that reached deep into the Arctic, the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Sailing depended on two things: favorable winds and open, ice-free water. By changing currents and cooling temperatures in the atmosphere and oceans, the chilliest stretches of the Little Ice Age therefore affected sailing as much as farming. Yet the impact was very different. New wind patterns actually sped up ships that left the republic for Asia or America, shortening their journeys. In the waters off northern Europe, storms were unusually frequent and severe in the coldest stretches of the Little Ice Age. Many ships foundered, and many sailors drowned. Yet crews aboard the republic’s biggest merchant ships – ones that carried the richest cargo from distant markets – weathered storms much better than sailors aboard other European ships. In fact, storms often benefitted Dutch sailors by further increasing the speed of these big ships. Even sea ice aided the Dutch, including in the Arctic. It took plenty of sea ice – but not too much – to redirect Dutch voyages of northern exploration towards the rich bowhead whale feeding grounds off the archipelago of Svalbard, which lies between the northern coast of Norway and the North Pole. Whalers from all over Europe soon set up shop there. For a long time, the edge of the Arctic pack ice lingered near Dutch whaling stations, and since whales gathered along the edge of the ice, the Dutch benefited. By following the ice edge west, Dutch whalers even found whale breeding grounds off the little island of Jan Mayen. The Dutch fought most of their wars on or around water. Climatic cooling may have benefited their armies and fleets even more than their merchants. The Dutch flooded their own farmland to thwart Spanish and later French invasions. Some of these floods would not have succeeded without torrential rains that reflected new atmospheric realities. Later in the seventeenth century, cooling coincided with a shift in the strength of atmospheric high and low pressure zones over the Atlantic Ocean, which sharply increased the frequency of easterly winds over northern Europe. Sailors aboard Dutch warships heading into battle from the republic often had what was then called the “weather gage:” the upwind position from a downwind opponent. That allowed them to decide exactly how and when to deploy new “line of battle” tactics, in which warships would sail by each other in single file while firing broadsides. New wind patterns played a role in helping the Dutch win wars they might otherwise have lost. Still, climate change did not always aid the Dutch. In the Arctic, sea ice crushed ships, drowned sailors, and screened whales from whalers. Sailors in small ships that carried grain and timber from the Baltic Sea endured violent storms and confronted thick sea ice that blocked their way. Cold snaps in the Baltic occasionally led to harvest failures that imperiled the republic’s precious grain imports. Ice repeatedly blocked the waterways of the republic, suffocating travel between cities and raising the specter of flooding when the ice thawed. Sometimes, ice froze rivers that otherwise served as barriers to invasion. Left unattended, candles and stoves in cold winter weather kindled fires that swept through the cities of the republic. Time and again, the Dutch responded creatively. Shipwrights fortified the hulls of whaling ships and greased them until they slid off ice. Civilians and soldiers hacked through ice to preserve open water in their defensive rivers. Guilds and city governments bought icebreakers that not only kept waterways open, but actually manufactured ice blocks for use in cellars. When the ice was too thick, the Dutch used skates and sleds to turn frozen canals into busy thoroughfares. Merchants divided their goods between different ships, and invested in marine insurance. They stockpiled Baltic grain in good years, and sold it for healthy profits whenever food shortages plagued Europe. Charities maintained a steady supply of food for the urban poor. Inventors pioneered new firefighting tactics and equipment, and made good money selling them across Europe. The Dutch, in short, were lucky to benefit from environmental changes that favored their unusual economy. But they also made their own luck. The society they built ended up being remarkably resilient in the face of new weather patterns that spelled disaster elsewhere in Europe. By relying so heavily on farmers scratching out a meagre existence on marginal farmland, other civilizations developed vulnerabilities to climate change that simply did not exist in the Dutch Republic. In fact, the Dutch may even have adapted their technologies and policies to exploit the Little Ice Age, though they may not have recognized the trends in weather that we call climate change. Why were they so flexible in the face of changing environmental circumstances? In part, the answer may lie in their long history of draining and damming the Low Countries. The Dutch long understood that environments can change, and that societies can either adapt or succumb. There was a darker side to the republic’s prosperity. The Dutch thrived in part by preying on communities and civilizations the world over. They shattered Iberian trading monopolies in Asia, seized expansive territories in the Americas, overwhelmed English whalers in the Arctic, and infamously broke into an African slave trade that cruelly exploited millions of people. The weather extremes of the Little Ice Age had often weakened communities that the Dutch victimized. In the republic, adaptation to climate change could take the form of a parasitic kind of opportunism that leveraged vulnerabilities in other societies. What, then, can the history of the republic’s frigid Golden Age teach us today? First and perhaps most importantly, it shows us that even relatively small changes in Earth’s average temperature can have enormous social consequences. Across much of the seventeenth-century world, the gloomiest predictions for our warmer future came true. A third of humanity may have died in disasters either set in motion or worsened by climate change. The world has already warmed more, relative to average temperatures in the twentieth century, than it cooled in the chilliest stretches of the Little Ice Age. Our best projections suggest that it will warm by roughly three degrees Celsius in the coming century, if and only if countries follow through on their Paris Agreement pledges. Histories of the Little Ice Age therefore give us an urgent call to arms. We have technologies that our ancestors could not have imagined. But there are far more of us, consuming unimaginably more plants and animals, metals and fuels. And we too depend on a huge network of fields and fisheries that may not survive drastic changes in temperature and precipitation. That leads us to our second lesson: climate change has had, and probably will have, very unequal consequences for different societies, communities, and individuals. Many assume that rich societies cope best with climate change. Yet some of the wealthiest seventeenth-century empires actually fared worst in the coldest and most volatile years of the Little Ice Age. Climate change, it seems, imperils not only societies that have few resources to exploit, but also those that require abundant resources to prosper. The Dutch thrived in the seventeenth century not because their republic was rich, but because much of its wealth derived from activities that climate change benefited. Today, we can learn from the republic by strengthening social safety nets, investing in technologies that exploit or reduce climate change, and more broadly by thinking proactively about how we will adapt to the warmer planet of our future. We can learn from the Dutch in another way too, by strengthening bonds between countries and communities, rather than preying on the most vulnerable. Ultimately, the lessons of the past come to us in the form of parables: stories that hint at deeper truths but do not tell us exactly what to do. That does not make them any less valuable. We now know that we cannot ignore our changing climate, that it will shape our fortunes in the decades to come. Let us use the warnings of the past to confront the looming catastrophe in our future, while we still can. This article summarizes some important ideas in my new book, The Frigid Golden Age: Climate Change, the Little Ice Age, and the Dutch Republic, 1560-1720. You can buy the hardcover on the Cambridge University Press website or on Amazon, and you'll soon be able to purchase the paperback.

The Washington Post published a modified and much shorter version of this article. You can find it here. |

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed