|

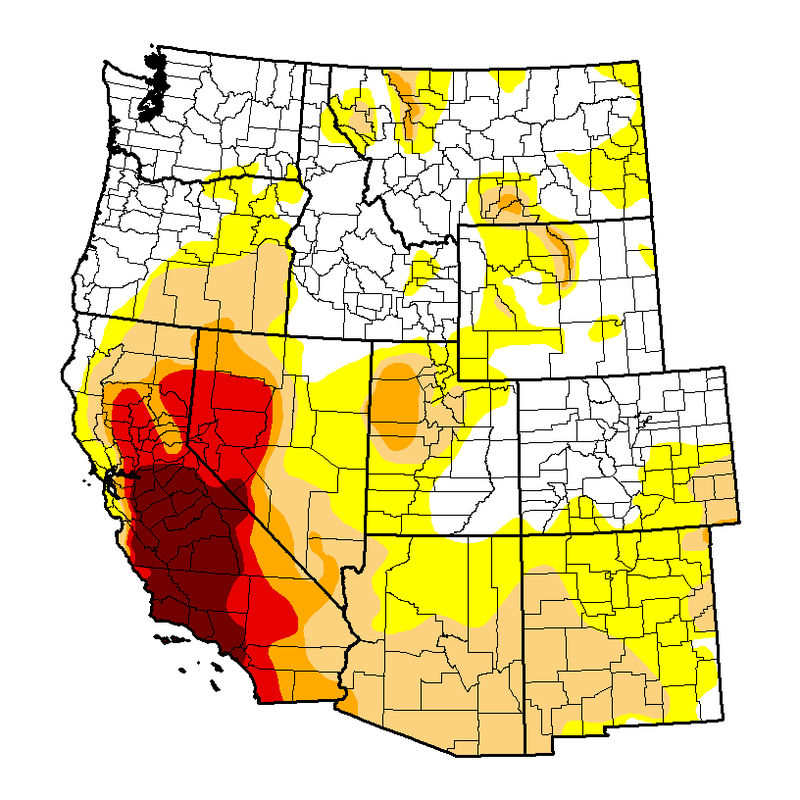

Dr. Ruth Morgan, National Centre for Australian Studies, Monash University At the 2016 American Society of Environmental History conference in Seattle, I joined Linda Nash (University of Washington), Char Miller (Pomona College), and Libby Robin (The Australian National University) to contextualize Western drought in environmental, historical and cultural terms. ‘Western drought’ in this instance referred to the region that the US Drought Monitor classifies as ‘West’, where some areas are still experiencing ‘exceptional’ drought conditions. Our discussion drew this Western experience into transnational conversation with histories of drought in Australia, further west across the Pacific. By providing a humanistic perspective of drought, the lens of environmental history complements the scientific study of climate conditions and offers valuable insights into how droughts have been understood and experienced over time.  The US Drought Monitor produces a weekly map of drought conditions based on measurements of climatic, hydrologic and soil conditions as well as reported impacts and observations drawn from around the United States. The US Drought Monitor is a joint initiative of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the US Department of Agriculture, and the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Regional conditions as of April 12, 2016. In late 2015, meteorologists watching the Pacific Ocean saw the signs of what the media described as the ‘Godzilla El Niño’. Ocean waters in the equatorial Pacific were unusually warm, one of the tell-tale signs that a very strong El Niño was brewing – stronger even than the catastrophic event of 1997-98. For the drought-stricken west coast of the United States, this forecast promised storms and heavy rains in California, while Australians feared the onset of worsening drought conditions over the inland areas of Queensland and northern New South Wales. Although this El Niño has yet to live up to the hype, with the Washington Post recently declaring it ‘dead’, its onset highlighted the climate connections between Australia and the American West and their shared experience of extreme weather events.  In August 2015, the Los Angeles Times compared the prevailing strength of the ‘Godzilla El Nino’ to the same time of year in 1997. The red and white patches depict the highest sea-surface heights above average, which indicate how warm sea-surface temperatures are above the average. Graphic: Bill Patzert, Climatologist, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Prolonged dry spells lay the ecological and hydrological foundations for fires and floods. In the aftermath of the catastrophic Black Saturday bushfires of 2009, which claimed the lives of 173 Victorians, environmental historian Tom Griffiths explained, ‘These are wet mountain forests that burn on rare days at the end of long droughts, after prolonged heatwaves, and when the flume is in full gear. And when they do burn, they do so with atomic power’. Last year, wildfires burned across a bone dry American West and authorities fear what the 2016 fire season might have in store. Alternatively, in the boom and bust climate of the Murray-Darling Basin, historian Emily O’Gorman has shown how a downpour can turn into a flood if it is ‘not “cushioned” by already full rivers’, while historian Jared Orsi explores flood control in the ‘hazardous metropolis’ of Los Angeles. Despite significant differences in population, economy and geography, both political and lay responses to drought over the past two decades reveal settler cultures that are at odds with the highly variable climates in which they live. In both Australia and the United States, drought has been a constant since English settlement: archaeologist Dennis Blanton has argued that Jamestown was founded at the height of an unprecedented dry spell, while environmental historian Richard Grove has shown that the arrival of the First Fleet in New South Wales in 1788 coincided with one of the strongest El Niño events in recorded history. Reconstructions of the pre-instrumental climate in southeastern Australia and California suggest the extent to which climate variability was a feature of colonial life.  Derived from qualitative sources, this table shows drought conditions in southeastern Australia between 1838 and 1860. Column R shows the number of regions affected by drought as a fraction of regions colonized by Europeans. Column M shows the number of months in a year that drought was reported. Source: Claire Fenby and Joëlle Gergis, 2012. Although some part of Australia and the United States is almost always in drought, the visitation of such dry conditions continues to be framed as abnormal, rather than the expression of a variable climate. This water culture, as I and others have argued, is the product of the rise of large-scale public water infrastructure. By separating the means of water production and consumption, this mode of water management helped render invisible the processes of water delivery, thus allowing the illusion of endless water supplies to develop. Our responses to drought continue to favor restoring the illusion of endless water supplies, instead of addressing the cultures that perpetuate this unsustainable vision. Droughts, like all disasters, invite historians to peel away this veneer, laying bare deep-seated tensions relating to land, race, class, and politics that water scarcity only serves to heighten. Like the Millennium Drought (1996-2010) in eastern Australia, the intensity of the recent drought in California (2011-) has been attributed to anthropogenic climate change. The IPCC warns that climate change will increase the likelihood and severity of such events in the future. In the southwest of Australia, meanwhile, climate change is also contributing to the regional drying trend that has been challenging local land and water managers since the 1960s. This drying trend is the result of the westerly winds, which are responsible for winter rains across southern Australia, inching south across the Southern Ocean and leading to greater snowfall in eastern Antarctica. In light of these changing climates, an audience member asked us, what then are the role and value of climate and environmental histories? I argue that in these uncertain times, climate and environmental histories are more important than ever. Our research reveals the histories of past weather and climate events, how they were experienced, and how the experience and interpretation of such events has changed over time. We can also map the connections between climate events; historical patterns of vulnerability; and technological and cultural path dependencies. Environmental historians William Cronon and Tom Griffiths have long counselled their colleagues to tell stories about the past, for narratives have the power to inform and most importantly, engage. Engagement is crucial for historians, not just through our stories but also through our research. Close collaborations with researchers and policymakers can reveal the historical thinking inherent to environmental management, while informing analyses of the present and plans for the future. ~Ruth Morgan BibliographyAustralian Context

Deb Anderson, Endurance: Australian Stories of Drought, CSIRO, 2014. Michael Cathcart, The Water Dreamers: The Remarkable History of Our Dry Continent, Text Publishing, 2010. Tim Flannery, The Weather Makers: the History and Future Impact of Climate Change, Text Publishing, 2008. Bill Gammage, The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia, Allen & Unwin, 2011. Don Garden, Droughts, Floods and Cyclones: El Niños that Shaped Our Colonial Past, Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2009. Joëlle Gergis, Don Garden and Claire Fenby, ‘The Influence of Climate on the First European Settlement of Australia: a Comparison of Weather Journals, Documentary Data and Palaeoclimate Records, 1788-1793’, Environmental History, 15 (3), 2010: 1-23. Tom Griffiths, ‘We Have Still Not Lived Long Enough’, Inside Story, 16 February 2009. Robert Kenny, Gardens of Fire: an Investigative Memoir, UWA Publishing, 2013. Ruth A. Morgan, Running Out? Water in Western Australia, UWAP, 2015. Emily O’Gorman, Flood Country: an Environmental History of the Murray-Darling Basin, CSIRO Publishing, 2012. Stephen J. Pyne, Burning Bush: a Fire History of Australia, University of Washington Press, 1998. Comparative and Global Studies Mike Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World, Verso, 2001. Henry F. Diaz and Vera Markgraf (eds), El Niño and Paleoclimatic Aspects of the Southern Oscillation, Cambridge, 1992. Michael H. Glantz, Currents of Change: Impacts of El Niño and La Niña on Climate and Society, 2nd ed., Cambridge, 2000. Richard H. Grove, ‘The Great El Niño of 1789-93 and its Global Consequences: Reconstructing an Extreme Climate Event in World Environmental History’, Medieval History Journal, vol. 10, 2007, pp. 75-98. Richard H. Grove and John Chappell (eds), El Niño – History and Crisis: Studies from the Asia-Pacific Region, White Horse Press, 2000. Ian Tyrrell, True Gardens of the Gods: Californian-Australian Environmental Reform, 1860-1930, University of California Press, 1999. US Context Dennis Blanton, ‘Drought as a Factor in the Jamestown Colony, 1607-1612’, Historical Archaeology, 34 (4), 2000: 74-81. Mike Davis, Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster, Metropolitan Books, 1998. William DeBuys, The Great Aridness: Climate Change and the Future of the American Southwest, Oxford, 2011. Norris Hundley Jr, The Great Thirst: Californians and Water, revised ed., University of California Press, 2001. B. Lynn Ingram and Frances Malamud-Roam, The West Without Water: What Past Floods, Droughts and Other Climatic Clues Tell Us About Tomorrow, University of California Press, 2013. Jared Orsi, Hazardous Metropolis: Flooding and Urban Ecology in Los Angeles, University of California Press, 2004. Stephen J. Pyne, California: a Fire Survey, University of Arizona Press, 2016. Marc Reisner, Cadillac Desert: the American West and its Disappearing Water, Penguin, 1993. Marsha Weisiger, Dreaming of Sheep in Navajo Country, University of Washington Press, 2011. Donald Worster, Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s, Oxford, 1979. Donald Worster, Rivers of Empire: Water, Aridity and the Growth of the American West, Oxford, 1992. Almost exactly six years ago, I created HistoricalClimatology.com and co-founded the Climate History Network with professor Sam White, an environmental historian then at Oberlin College. At the time, I was a PhD student at York University in Toronto, Canada. I had recently completed the comprehensive exams that, in North America, qualify PhD students to begin writing their dissertations, and I was fresh from a visit to a Dutch archive. I thought that I could build a platform - this website - that would let me share what I learned as I researched and wrote my dissertation. At the same time, I hoped to build a network that would help me find like-minded scholars, and at the same time provide a new way for my field to grow. After just a few months, I realized that I was onto something, but not quite in the way that I had expected. Sam and I quickly saw that, if the Climate History Network was going to get off the ground, we had to work harder than we had anticipated. We had built a rough framework that allowed scholars of past climates to create fresh online content for themselves. Yet, that is not what most of our users wanted. They needed us to construct a resource that provided information and tools to sustain a new kind of scholarship, while connecting them to like-minded researchers around the world. We understood that it would take a while to build something like that, and we couldn't do it all ourselves. I had a very different challenge with HistoricalClimatology.com. By the end of 2010, it was on course to receive 10,000 hits for the year: far more than I expected for a website with a long domain name, a dated design, and, as yet, very little content. Clearly, there was a thirst, within academia and the broader public, for insights into climate change that drew both from the humanities and the sciences. I had a choice. I could keep the site about me, and thereby increase my name recognition in my field, and among laypeople interested in climate change. Alternatively, I could transform the site into something much bigger than myself: a major resource that could link scholarship on past climates to discussions about our warmer future. That second approach carried big risks. It would require a lot of work to build something credible, and I wasn't sure if I had the necessary time, skills, or prestige. It would also disassociate my name with something I had built, just as it was becoming popular. If you've ever met a PhD student, you'll know that most think obsessively about the advantages they might gain on the academic job market. By changing HistoricalClimatology.com, I worried that I was shooting myself in the foot. After a few weeks of indecision, I changed the site in early 2011. I was going to build a major resource that wouldn't be about me, although I accepted that I would need to do the work that would get it off the ground. By 2012, this site covered the big stories in historical climatology and climate history, with short monthly or bimonthly articles. It also offered links and graphs for laypeople interested in past climates, and a bibliography that was the first of its kind, anywhere on the Internet. In March, the site was referenced in a BBC News article that covered the emergence of historical climatology as a multidisciplinary research field. At around the same time, I started writing articles for other websites that referenced HistoricalClimatology.com. I also added links to Wikipedia pages about, for example, the Little Ice Age or the Medieval Warm Periods. Meanwhile, my articles on this site grew longer and more scholarly. By 2013, HistoricalClimatology.com received more than 50,000 hits annually. That year, I attended a scientific conference in India, and was surprised to discover that some of the scientists there knew me from the website that I had built. In India, I met a young graduate student - Benoit Lecavalier - who shared my interest in tracing climate changes through deep time. Benoit was a Master's student in physics. He worked in time periods, and on scales, that are often inaccessible to historians. I asked him to contribute to HistoricalClimatology.com, and he agreed. Soon after, I started searching for a social media editor who could expand the reach of both this website and of the Climate History Network. Before long, PhD student Eleonora Rohland, then researching the environmental history of hurricanes, accepted the position. When Eleonora was ready to pass the position to someone new, I posted a call for applications that received responses from several excellent candidates. I selected Bathsheba Demuth, then a PhD student who not only explored the environmental history of the Arctic, but had spent several years living there. Last year, Nicholas Cunigan, a PhD student studying the climate history of the Dutch West India Company, joined the Climate History Network as our newsletter editor. I still created almost all of the content at HistoricalClimatology.com, and a good share at the Climate History Network homepage. Yet increasingly, I belonged to a team of like-minded scholars. A lot of things changed in 2015, not only for me but for the climate history resources I helped create. In August, I joined Georgetown University as a tenure-track assistant professor of environmental history. I won awards from Georgetown that let me expand and redesign HistoricalClimatology.com and the Climate History Network website. Meanwhile, our popularity soared. Last year, this site received around 200,000 hits. The Climate History Network homepage received fewer hits - just under 20,000 - but many of these are from scholars who use our resources to support their scholarship and teaching. We launched the Climate History Podcast, which currently features quarterly interviews with major figures in climate change scholarship.

I view this as the beginning of the end of the process that I started back in 2011, when I transformed this website into something less focused on my own scholarship. Increasingly, our climate history websites will not only continue to reach a broader audience, but also feature insights from a range of senior and junior scholars in the sciences and the humanities. Diverse scholars, at Georgetown and elsewhere, will now help me build our websites, write our feature stories, update our social media feeds, improve our tools, and expand the reach of scholarship into past climates. We will expand offline, by hosting climate history workshops at Georgetown, as well as a major conference dedicated to connections between climate changes and conflict. To that end, we now have a large team of young professors and graduate students in climate history. These are the people who will help develop our resources in the coming years, in no particular order: Dr. Dagomar Degroot: Director, HistoricalClimatology.com, Co-Director, Climate History Network. Assistant professor of environmental history, Georgetown University. Dr. Sam White: Co-Director, Climate History Network. Associate professor of environmental history, Ohio State University. Bathsheba Demuth: Assistant Director, HistoricalClimatology.com and the Climate History Network. PhD candidate in environmental history, University of California, Berkeley, and incoming assistant professor of environmental history, Brown University. Nicholas Cunigan: Newsletter Editor, Climate History Network. PhD candidate in environmental history, University of Kansas, and adjunct professor of history, Calvin College. Faisal Husain: Project Editor, HistoricalClimatology.com. PhD candidate in environmental history, Georgetown University. Matthew Johnson: News Editor, Climate History Network. PhD candidate in environmental history, Georgetown University. Katrin Kleemann: Social Media Editor, HistoricalClimatology.com and the Climate History Network. PhD candidate in environmental history, Rachel Carson Center. Benoit Lecavalier: Contributing Editor, HistoricalClimatology.com. PhD candidate in physics and physical oceanography, Memorial University. If you want to read more about us, you can visit the "People" page of HistoricalClimatology.com, and the "About Us" page of the Climate History Network website. I am delighted to work with such talented and industrious colleagues, and I'm looking forward to seeing where we can go from here. If you have any suggestions, please do not hesitate to contact me. ~Dagomar Degroot |

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed