Ecological Militarism: The Unusual History of the Military’s Relationship with Climate Change5/25/2018

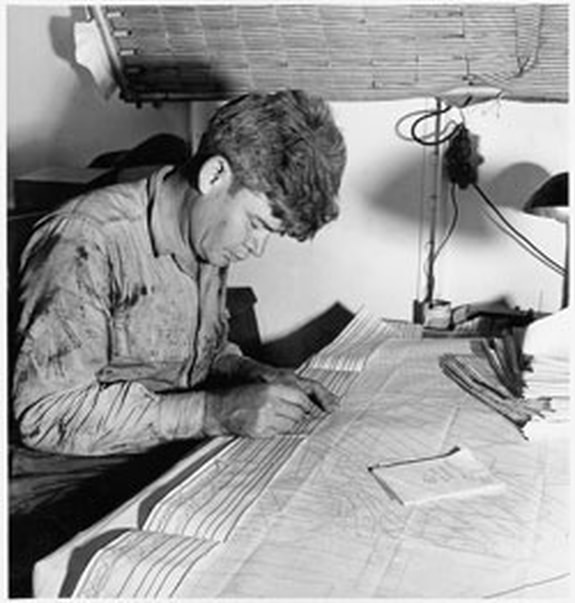

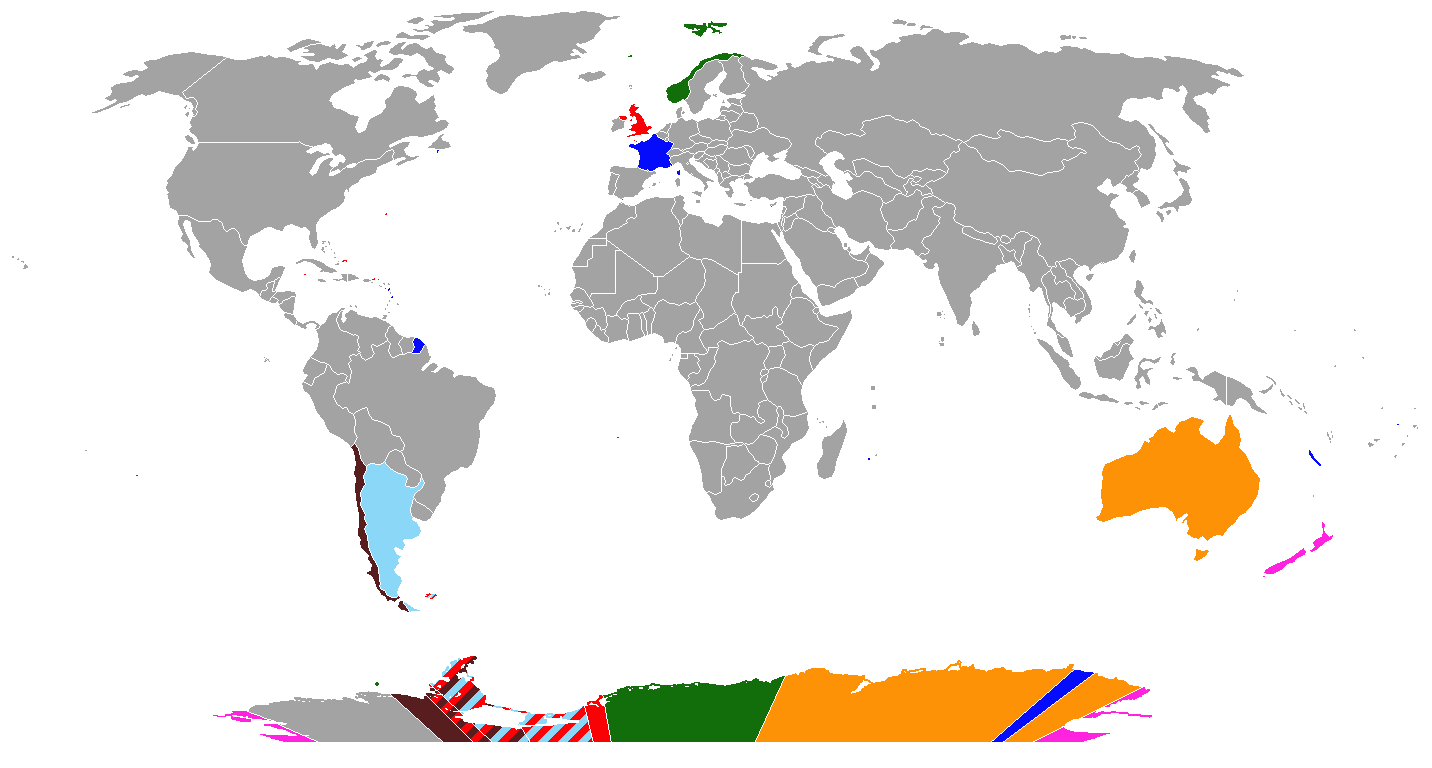

Adeene Denton, Brown University Many historians have discussed the influence of the Cold War on the development of specific disciplines within the broader field of earth science. However, few have touched on U.S. military’s study of and attempt to capitalize on climate change, an interest that accelerated rapidly during the Cold War. The decades-long studies sponsored by the Departments of Defense and Energy during and after the Cold War produced a wide array of attempts to transform the earth itself into a political and environmental weapon. The concept of anthropogenic climate change (also known as global warming) captured the world’s attention when James Hansen and other scientists testified before Congress in a series of hearings between 1986 and 1988. However, it had for decades been a subject of debate in smaller scientific, political, and corporate communities. Throughout the Cold War, American political and military leaders considered the potential of specifically directed, human-engineered climate change. They believed that cloud seeding and the atomic bomb, among other tools, would allow them to wield the geological force necessary to control Earth’s climate. Anthropogenic climate change was therefore a concept that excited many U.S. military planners during the early Cold War. Yet these planners, and the scientists and politicians who supported their efforts, struggled with the colossal scale of their desires. They yearned to use human technology to shape the Earth to their political will, but found themselves stymied by the very technologies and politics they sought to control. When the Earth Became Global For a science that is built on the concept of change over inconceivably long timescales, earth science developed at a breakneck pace during the Cold War. As earth science grew both in numbers of people working under its banner and the amount of data they had at their disposal, the field subdivided rapidly (in a case of science imitating life). The 1950s saw a fascinating dual development within earth science: scientists were increasingly recruited to work with and for their national militaries, even as they developed datasets and connections with other scientists that were global in nature. Scientists who wanted to study the history of the earth were looking for datasets that spanned the world, not just their country’s borders. They could only compile them through extensive collaboration with other nations, on the one hand, or, on the other, the vast quantities of funding and manpower that only a major military could offer. Oceanographers chose the latter option as their best chance for technological exploration of the oceans. U.S. naval vessels became the hosts of scientific research cruises, as they had the greatest mobility and most advanced technology of any ships in the world. Many scientists collecting these data were loath to discuss the tensions between their research and any political agendas, but it was certainly on their minds – and on the minds of their benefactors. For the Navy and the other branches of the U.S. military, scientific projects typically served multiple purposes. The data collected provided both a research boost to a specific scientific community, and information that the military might be able to use. Radio arrays in the Caribbean, for example, which were ostensibly used for ocean floor sounding and bathymetric mapping, also scoured the sea for Soviet submarines. Overall, the military hoarded big data about the earth and its climate for use in future tactical and strategic plans. Climate and environmental science became yet another venue in which the Cold War was fought. Yet the relationship between climate science and the political interests that funded it was an uneasy one. When researchers in conversation with the military realized that humanity was becoming a force that could act on a geologic scale, the possibility of extending U.S. control to the environment became extremely appealing to military planners. As American oceanic scientists saw the bathymetry of the seafloor for the first time, the political and military forces in Washington were haggling over just how much ocean the U.S. could control outside its borders. American oil companies like Chevron and Mobil became technological giants over the course of the Cold War by expanding their search for petroleum to South America and Africa, and their profits seemed to suggest that the earth’s interior was also within the scope of human knowledge and jurisdiction. After 1957, the dawn of the space age seemed to herald the beginning of total surveillance from above, and for the military planetary surveillance was the beginning of integrated planetary control. The more scientists discovered about the earth on which they lived, the more their military partners sought to use that information to bring the earth to heel. All of these ideas seemed to coalesce together during the Cold War, yielding decades of oscillating cooperation and struggle between the U.S. military and the scientists it patronized. The Military as a Geological Force During the early Cold War, U.S. military planners often proposed schemes to transform environments on immense scales, only to quickly abandon them either in the proposal stage or after initial testing. The initial popularity of such ideas, as well as their typically quick demise, owed much to military ambitions far exceeding capability. Environmental control was an undeniably powerful concept, as it promised ways to turn the tides of war through untraceable methods, or from continents away. Unfortunately, the military’s tactical plans to utilize newfound climate information often took unusual (and unusable) turns because much of the information was very new, and because experts consulted were not always well versed in the information they handled. Climate science was a field in its infancy, and not everyone who claimed to speak on its behalf understood the data. A classic example of this phenomenon was proposal developed by Hungarian-American polymath John von Neumann to spread colorants on the ice sheets of Greenland and the Antarctic. By darkening the ice, the military could reduce their reflectivity, or albedo, which would warm the poles, melt the ice, and ultimately flood the coastlines of hostile nations. It was an absurd idea proposed by a brilliant physicist who did not yet grasp how global the effects of such a plan would be. Melting of the Greenland ice sheet in particular would have drastic impacts on the North American continent as well as the intended target. The U.S. Departments of Energy and Defense, as well as President Eisenhower, were also interested in using humanity’s newfound power for good, however. Operation Plowshare, for example, was the name given to a decades-long series of attempts to use nuclear explosives for peaceful purposes, particularly construction. It resulted in of proposals such as Project Chariot in 1958, which called for the use of five thermonuclear devices to construct a new harbor on the North Slope of Alaska. Scientists were often split in their reactions to these proposals, a conflict provoked by their valuable relationship with the U.S. government, on the one hand, and risk to terrestrial environments they were only beginning to understand, on the other. Mud, Not Missiles: Weaponizing Weather in Vietnam When the U.S. military started seriously considering the possibility of human-driven climate warfare, its planners focused on a concept that has been human minds for centuries: controlling the weather. Weather modification has preoccupied scientists, politicians, and the military in the U.S. since James Espy, the first “national meteorologist” employed by the military, studied artificially-produced rain in the 1840s. In the early Cold War, such projects continued to intrigue military planners. In 1962, the U.S. military launched Project Stormfury, an attempt by researchers at the Naval Ordinance Test Station (NOTS) to test weather control by seeding the clouds of tropical cyclones. They hoped to weakened hurricanes that regularly wreaked havoc on the southern and eastern coasts of the United States. They theorized that the addition of silver iodide to hurricane clouds would disrupt the inner structure of the hurricanes by freezing supercooled water inside. Yet their cloud seeding flights revealed that the amount of precipitation in hurricanes did not appear to correlate at all with whether a cloud had been seeded or not. In the meantime, however, members of the U.S. high command used the theory behind Stormfury as a basis for two similar operations in Asia: Projects Popeye and Gromet. Despite Project Stormfury’s failure to deliver measurable results, the need for any kind of interference that could harry the Viet Cong led military planners to rush Popeye into the testing phase. The scientists recruited to assist with Popeye slightly modified Stormfury’s cloud seeding approach. They decided to use lead iodide and silver iodide in large, high-altitude, cold clouds, which (in theory) would then “blow up” and “drop large amounts of rain” over an approximately targeted area. If successful, Popeye would increase the rainfall during the monsoon season over northern Vietnam, hampering their forces by destroying their supply lines. This would lengthen the monsoon season, which would force the Vietcong to deal with landslides, washed out roads, and destroyed river crossings. American officials had also promised the Indian government that they could seed clouds to end a crippling drought in India. Cloud seeding, military planners, could both win allies and cripple enemies. Despite the eagerness and ambition with which the U.S. military undertook testing of this method in both India (with government permission) and Laos (without informing the Laotian government), it was ultimately unclear whether these attempts at “rainmaking” were effective at all. The utmost secrecy with which Projects Gromet (in India) and Popeye (in Laos and Vietnam) were undertaken limited attempts to measure and verify their success. Gromet alone cost a minimum of $300,000 (nearly $2 million in present-day US dollars), yet by 1972 U.S. officials had to concede that its effectiveness had been unclear at best. The Indian drought ended, but no one could say whether it was the U.S. that had done the job. Politics, Military, and Oceans For scientists, the ocean represents a crucial biological and chemical reservoir whose massive size makes any fluctuation of oceanic conditions a crucial aspect of climate change. In the early Cold War, the oceans also became a focus for the development of poorly conceived climate control plans, as well as a site for political posturing. There were two basic prongs to the American (as well as other countries’) political and military approach to the oceans during the Cold War. First, the oceans were seen as a way to extend a country’s sovereign borders, and second, as a mechanism for disposing of unsavory nuclear waste. As American scientists followed the Navy to exceedingly remote places in search of new datasets, the question of nationalism followed them. Where could the Navy “plant the flag” as part of its surveys? Polar scientists who sought direct access to their regions of interest – the Arctic and Antarctic – were hamstrung by the security interests of not just their own nations, but also of others. The U.S. government, which noted the conveniently large strip of polar access given by USSR’s ~7,000 km of Arctic coastline, pushed to extend its sovereignty as far off of Alaska’s northern continental shelf as it could. Where scientists saw the Arctic as a fascinating environment and ecosystem, the U.S. military saw a direct route to its biggest enemy. In Antarctica, meanwhile, by the International Geophysical Year (1957-1958) over seven different countries had laid claim to large swaths of the frozen continent. The British had already secretly built a base on Antarctic Peninsula during World War II to supersede other claims to the area. Establishing the Antarctic continent as a zone that was to be as free from geopolitics as possible (as well as exploitative capitalist interests) was a difficult task, and one that took decades. It took until the Clinton administration for oil companies to be officially banned from prospecting on or near the continent, essentially reserving Antarctica as a place where only collaborative science could reign. As the U.S. and other major powers jockeyed with each other for territory in the most remote areas of the world, they also used the ocean as a garbage disposal for some of humanity’s most toxic waste. Between 1946 and 1962, the United States dumped some 86,000 containers of radioactive waste into the oceans, while Britain, the USSR, and other developing nuclear powers did much the same. Meanwhile, scientists from the International Scientific Committee on Ocean Research started collecting data on the possible dangers associated with radioactive waste. However, governments funding their research had little interest in the results until U.S. waste washed back up onto American shores where local fishermen found and identified it. For years, the ocean was convenient to U.S. officials. Its volume seemed limitless: perfect for permanently keeping radioactive waste, and any information about it, from the public eye. Fortunately, oceanic waste dumping did not stay a secret forever. There was, it seemed, no convenient way to dispose of radioactive waste. Dumping it on land provoked public criticism at home, and dumping it in the oceans invited international criticism, particularly from the Soviet Union, whose government claimed to have never done such a thing. In fact, it did; the USSR sank eighteen nuclear reactors in addition to packaged waste, a fact only revealed in declassified archives after the Soviet Union collapsed. To describe the relationship between the U.S. government and the oceans during the Cold War as fraught would be an understatement. The Navy wanted the ocean to be an effective source of information on Soviet activities, a convenient landfill, and a platform to extend American political authority. In the end, the Navy could not have it all. By the end of the Cold War, the Navy and its political supporters had to concede to public and scientific pressure to back away from large-scale projects that overtly exploited the ocean. The power jockeying and technological exploitation during the Cold War did have lasting effects, however. Today, the oceans remain a site of intense monitoring and political grandstanding. The Cold War and the Warm Future In his speech to the National Academy of Sciences in 1963, President Kennedy noted that human science could now “irrevocably alter our physical and biological environment on a global scale.” This was a fundamental realization – that humans could change the world, and they could do it in a matter of minutes to years if they chose. The Cold War forced scientists and their military benefactors to realize that humans had become more efficient at shaping the Earth than most geological forces in existence. It was tempting, then, for Cold War militaries to investigate just how far that power could go, in both destructive and constructive ways. Can we lengthen or shorten the seasons? The military tried it. Can we disappear our worst waste in the oceans? Every country with nuclear waste tried it. How much do we need to know about the environment before we can begin to reshape whole regions to suit nationalistic goals and objectives? For the military during the Cold War, the answer was almost always “we know enough.” For some of the scientists they employed, and many more whom they didn’t, the answer was “we may never know enough.” Popular discussions rarely touch on the outlandish attempts to control nature during the early Cold War. In our present age of polarization around the issue of climate change, perhaps they should. Politicians and scientists too often assume that humanity will someday engineer a solution to climate change, but the Cold War’s history reveals that our grandest schemes may be the most susceptible to failure. Selected References Doel, R.E. and K.C. Harper (2006). “Prometheus Unleashed: Science as a Diplomatic Weapon in the Lyndon B. Johnson Administration.” Osiris 21, 66-85.

Fleming, J.R. Fixing the Sky: The Checkered History of Weather and Climate Control. Columbia University Press: New York City. 2010. Hamblin, J.D. (2002). “Environmental Diplomacy in the Cold War: The Disposal of Radioactive Waste at Sea during the 1960s.” The International History Review 24 (2), 348-375. Marzec, R.P. Militarizing the Environment: Climate Change and the Security State. University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis. 2015. Naylor, S., Siegert, M., Dean, K., and S. Turchetti (2008). “Science, geopolitics and the governance of Antarctica.” Nature Geoscience 1. O’Neill, Dan (1989). “Project Chariot: How Alaska escaped nuclear excavation.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 45 (10). “Text of Kennedy’s Address to Academy of Sciences,” New York Times, Oct 23, 1963, 24. |

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed