|

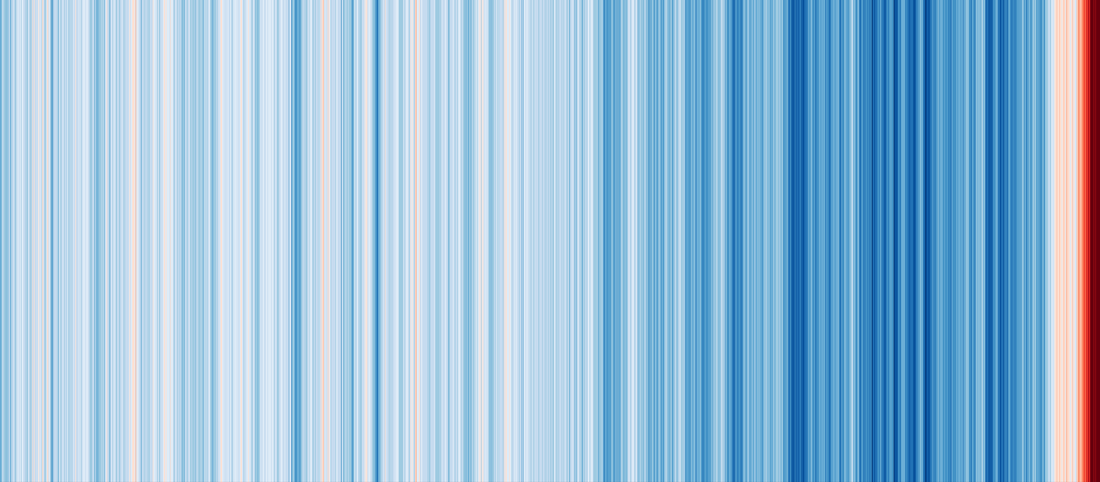

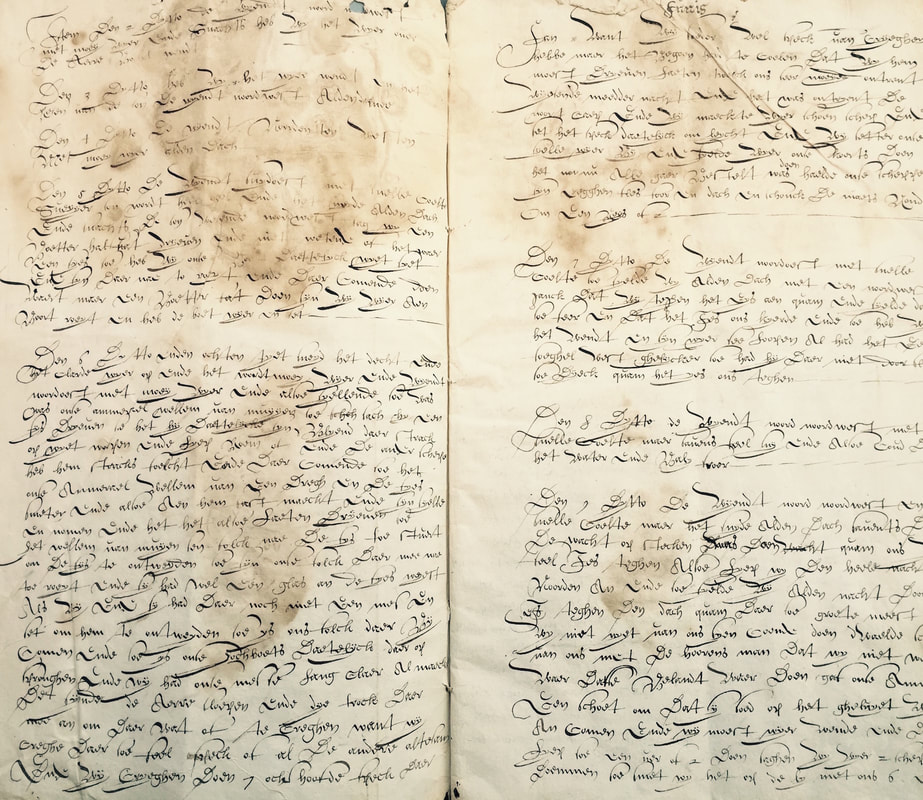

Dr. Dagomar Degroot, Georgetown University Students often ask me: how did climate history – the study of the past impacts of climate change on human affairs – come to be? I usually give the origin story that’s often told in our field: the one that sweeps through the speculation of ancient and early modern philosophers before arriving in the early twentieth century with the emergence of tree ring science and the theories of geographer Ellsworth Huntington. Huntington’s ideas perpetuated a racist “climatic determinism,” I say, but his imprecise evidence for historical climate changes meant that few historians took his claims seriously. Then, in the 1960s and 70s, the likes of Hubert Lamb, Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, and Christian Pfister developed new means of interpreting textual evidence for past climate, and used these methods to advance relatively modest claims for the impact of climate change on history. Their care and precision gave rise to climate history as it exists today – though the field did not attain true respectability until recently, when growing concerns about global warming encouraged many historians to reappraise the past. It’s a compelling story, and true in many respects. Yet it has a problem. Crack open Huntington’s publications, and it’s immediately obvious that there’s an uncomfortable similarity between them and many of the most popular publications in climate history today. Like Huntington, most climate historians write single-authored manuscripts. Like Huntington, many learn the jargon and basic concepts of other fields – such as paleoclimatology – before concluding that this knowledge allows them to identify significant anomalies or trends in past climate. Like Huntington, modern climate historians have assumed that societies were homogenous entities, with some more “vulnerable” to climatic disruption than others. They routinely focus on the rise and fall of societies, typically by focusing on the “fatal synergy” of famines, epidemics, and wars. Such narratives have been influential, and the best of them have helped transform how historians understand the causes of historical change. It is under the scrutiny of climate historians – and many other scholars who consider past environments – that the historical agency or “actancy” of the natural world has gradually come to light. Few historians would now argue that humans created their own history, irrespective of natural forces. Climate historians have also shown that the “archives of nature” – materials in the natural world that register past changes – can be as useful for historical scholarship as the texts, ruins, or oral histories that constitute the “archives of society.” And like other scholars of past climate change, historians have offered fresh perspectives on the challenges of the future: perspectives that may reveal what we should most fear on a rapidly warming Earth. Yet precisely because climate history has become an influential and dynamic field within the historical discipline, it is time to consider how it might be improved. Among other avenues for improvement, it is time to imagine how the field might transcend some of Huntington’s assumptions. It is time to consider how it could be better integrated within the broader scholarship of climate change, and thereby how historical perspectives might genuinely contribute to the creation of policies for the future. And it is time to ask whether the stories climate historians have been telling – those narratives of societal disaster – really represent the most accurate or useful way of understanding the past. I started thinking about that question while working on The Frigid Golden Age, a book that grew out of my doctoral dissertation. When I began my PhD at York University, I assumed my dissertation would confirm that the Dutch Republic, the precursor state to the present-day Netherlands, shared in those fatal synergies that climate historians had linked to the Little Ice Age. After a few months under Richard Hoffmann's tutelage, I learned that a group of scholars had digitized logbooks written by sailors aboard Dutch ships. I realized that those logbooks would allow me to start my research before I could travel to the Netherlands. Working with logbooks encouraged me to look beyond the famines and political disasters that had dominated scholarship on the Little Ice Age. Rather than searching for the climatic causes of disasters, I started thinking about the influence of climate change on daily life (aboard ships). It dawned on me that I could no longer rely on existing reconstructions of temperature or precipitation, which have less relevance for marine histories. I needed to learn more about atmospheric and oceanic circulation, which meant that I had to begin to understand the mechanics by which the climate system actually operates. I had to consider how circulation patterns manifested at small scales in time and place, so I had to think carefully about what it meant when one line of evidence (or “proxy”) – my logbooks, for example – contradicted another. Gradually, I learned to abandon my earlier assumptions, and to reimagine modest climate changes – such as those of the Little Ice Age – as subtle and often counterintuitive influences on human affairs. It didn’t surprise me when, shortly before I finished my PhD, a landmark book in climate history lumped the Dutch in among other examples of societies that shared in the crises of the Little Ice Age. By then I was framing the Republic as an “exception” to these crises, a unique case in which the impact of climate change was more ambiguous than it was elsewhere. Now, I started to wonder: was the Republic really as big of an exception as I had thought? Or were the crises of the Little Ice Age less universally felt than historians had assumed? Had climate historians systematically ignored stories of resilience and adaption? It was a question with significant political implications. By the time I arrived at Georgetown University in 2015, “Doomism” – the idea that humanity will inevitably collapse in the face of climate change – was just beginning to take off. In popular articles and books it relies primarily on two things: a misreading of climate science (occasionally with a heathy dose of skepticism for “experts” and the IPCC), and an accurate reading of climate history as a field. Past societies have crumbled with just a little climate change, Doomists conclude – why will we be any different? At around the time I published The Frigid Golden Age in 2018, I noticed that more of my students were beginning to echo Doomist talking points. I worried, because in my view Doomism is not only scientifically inaccurate, but also disempowering. If collapse is inevitable, why take action? It seemed perverse that the idea would gain momentum precisely as young, diverse climate activists were at last raising the profile of climate change as an urgent political issue. It seemed that now was the time to return to the question that had bothered me as a graduate student. So it was that I applied for a little grant from the Georgetown Environment Initiative (GEI), a university-wide initiative that connects and supports faculty working on environmental issues. I asked the GEI for funds to host workshops that would bring together scholars who had begun to study the resilience of past communities to climate change. Through discussions at those workshops, I hoped to draft an article that would highlight many such examples – and perhaps systematically analyze them to find common strategies for adaptation. The goal would be submission to a major scientific journal: precisely the kind of journal that had helped to popularize the idea that societies had repeatedly collapsed in the face of climate change. I soon realized that the workshops would have to connect scholars in many different disciplines, not just history. A striking series of articles was just then beginning to call for “consilience” in climate history: the creation of truly interdisciplinary teams wherein sources and methods would be shared to unlock new, intensely local histories of climate change. My experiences as the token historian on scientific teams that had developed their projects long before asking me to join had by then caused me to doubt the utility of working on research groups. Yet the new concept of consilience - and conversations with my new colleague Timothy Newfield - convinced me that there was much to be gained if scholars in many disciplines worked together to develop a project from the ground up. Eventually I learned that the GEI would award me enough money to host one big workshop at Georgetown. That was exciting! Arrangements were made, and before long Kevin Anchukaitis, Martin Bauch, Katrin Kleemann, Qing Pei, and Elena Xoplaki joined Georgetown historians Jakob Burnham, Kathryn de Luna, Tim Newfield, and me in Washington, DC. After a fruitful day of discussion, my colleagues suggested a change of focus. Why not consider how climate history as a field could be improved by telling more complex stories about the past? It was a compelling idea, but I added a wrinkle. What if those more complex stories were also often stories about resilience? To me, complexity and resilience could be two sides of the same coin. We decided to focus our work on periods of climatic cooling in the Common Era – the last two millennia – and accordingly I began to refer to our project as “Little Ice Age Lessons.” Then we settled on a basic work plan. I would draft a long critique of most existing scholarship in our field. Meanwhile, our paleoclimatologists would collaborate on a cutting-edge summary of both the controversial Late Antique Little Ice Age, a period of at least regional cooling that began in the sixth century CE, and the better-known Little Ice Age of (arguably) the fourteenth to nineteenth centuries. It had dawned on me while writing The Frigid Golden Age that many climate historians took climate reconstructions at face value, especially badly dated reconstructions, and used them to advance claims that no paleoclimatologist would feel comfortable making. One recent, popular book, for example, claims that the Little Ice Age cooled global temperatures by about two degrees Celsius; that's off by around an order of magnitude. False claims about climate changes lead to erroneous assumptions about the impact of those changes on history, and dangerous narratives about the risks of present-day warming. With our study, we hoped to model how to use - and not use - paleoclimatic reconstructions. I would work with one paleoclimatologist in particular – Kevin Anchukaitis of the University of Arizona – to reappraise a statistical school of climate history that quantifies social changes in order to find correlation, and therefore causation, between climatic and human histories. By applying superposed epoch analysis – a powerful statistical method that can accommodate lag between stimulus and response – to global commodity databases, we hoped to identify correlations that statistically-minded climate historians had missed, or else interrogate correlations that they had already made. Finally, our historians and archaeologists would contribute qualitative case studies that would each reveal how a population had been resilient or adaptive in the face of climate change. I hoped that these case studies would address my criticisms of our field, partly by relying on the cutting-edge reconstructions our paleoclimatologists would provide. While our initial group would have plenty of case studies to share, I immediately reached out to solicit more and more diverse examples of resilience, primarily from those parts of the world that Little Ice Age historians had most frequently linked to disaster. In the coming months, Fred Carnegy, Jianxin Cui, Heli Huhtamaa, Adam Izdebski, George Hambrecht, and Natale Zappia joined our team. Kevin soon became an indispensable partner. As the months went by, we exchanged countless messages on just about every concern I could come up with, most of which initially dealt with how to identify and interpret regional paleoclimatic reconstructions. After I found and began to interpret commodity price databases from across Europe and Asia, we began our statistical analysis. I was surprisingly unsurprised when we uncovered no decadal correlations between temperature or precipitation trends and the price of key staple crops across China, India, the Holy Roman Empire, France, Italy, or the Dutch Republic. In fact, we found no correlations even between annual temperatures and prices. We did find that precipitation anomalies correlated with price increases, but only during a small number of extreme years. These results, I thought, could be really important. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of publications in climate history all assume a relatively direct link between climatic trends, grain yields, and food prices. In fact, many studies conclude that it is from this basic relationship between climate change and the cost of food that all the economic, social, political, and cultural impacts of climate change follow, past or present. Had we found compelling statistical evidence that connections between climatic and human histories were subtler and more complicated in the Common Era than previously assumed? Maybe not. Kevin worried that we were falling into precisely the tendency that we hoped to criticize in our article: the temptation to reach grand conclusions on the basis of flimsy correlations. Heli Huhtamaa, who authored some of the most important scholarship that links climate change to harvest yields, soon explained that our price data did not necessarily reflect changes in yields - and that our price databases were far from comprehensive. Adam Izdebski consulted economic historian Piotr Guzowski, who pointed out that the gradual process of market integration in the early modern centuries may have blunted the impact of harvest failures (we would later stress this integration as a source of resilience). At the same time, I conferred with climate modeler Naresh Neupane, who asked insightful questions about our statistical methods. I also consulted leading climate historian Sam White for his perspective. He argued that in order to reach persuasive conclusions, we needed to develop or adopt a model for the impact of climate change on agriculture. Only then could we understand what our price series and correlations – or lack thereof – were telling us. I had mixed feelings – shouldn’t our impact model flow from our data, rather than the reverse? – yet I asked Georgetown PhD student Emma Moesswilde to join our team by sorting through just about every model ever developed by climate historians. As I suspected she would, Emma concluded that most assumed a relatively direct link between temperature, precipitation, harvest yields, and staple crop prices. Meanwhile, our case studies were beginning to flow in. I had established a hands-on workflow, with a constant pace of reminder emails and shared Google folders and files. I was incredibly fortunate to work with brilliant and motivated colleagues who collectively met our deadlines, despite many other commitments and pressures. By the summer of 2019, I had nearly every case study that would enter our article. Now it was a process of shortening each case study from several pages to about a paragraph each . . . then finding connections between them, organizing them according to those connections, and interrogating them using our cutting-edge climate reconstructions. The weeks dragged by. I hazily remember working long hours late into the night or in the wee hours of the morning, while my newborn son refused to sleep. If integrating our case studies was difficult, I found it surprisingly easy to criticize our field. Climate historians, I argued, had often misused climate reconstructions, and many uncritically followed methods that ended up perpetuating a series of cognitive biases. While climate history was multidisciplinary, it was not yet sufficiently interdisciplinary, meaning that it was still unusual for scholars in a truly diverse range of disciplines to work together. The upshot was that many publications were unconvincing either because they misjudged evidence, ignored causal mechanics, did not attempt to bridge different scales of analysis, or did not pay sufficient attention to uncertainty. By the fall, it was clear to me that something exciting might be taking shape. When Kevin joined us at Georgetown for a few days, he suggested that we might consider submitting to Nature, the world’s most influential journal. I found the idea tremendously exciting, if daunting. While still a young child I’d dreamed of publishing in Nature, inspired perhaps by tales told by a much-older brother who was then pursuing a doctorate in neuroscience. Now I thought of the influence our publication could have if Nature would publish it – and of career-altering ramifications for our graduate student co-authors in particular. I also thought about what it might do not only for the field of climate history (and relatedly, environmental history) but also more broadly for the transdisciplinary reach and prestige of qualitative, social science and humanistic scholarship. When fall turned to winter, I submitted a synopsis of our article to Nature, and early in the next year I was delighted (and frankly surprised) to receive an encouraging response. Our editor, Michael White, suggested that he would be interested in a complete article – but only if we considered including a research framework that would allow climate historians to address our criticisms. It was a crucial intervention. Kevin and I had worried that the part of our article that dealt with reconstructions and criticisms was becoming increasingly distinct from our statistical and qualitative interpretations of history. Yet a framework could allow us to convincingly bridge these halves. Michael asked whether we wished to submit a Nature Review, a format that would give us a bit more space and much more latitude to adopt our own structure. Yet space was still at a premium, and with our article so packed for content we decided that our statistical analysis had to go. This was a painful choice for me. While several co-authors remained skeptical, I considered it to be important, if incomplete, and I wonder whether to pursue its early conclusions in a future publication. Commodity prices do not tell us directly how climate anomalies influenced agriculture, yet to me the lack of statistically significant correlations between those anomalies and prices could still reveal something important about the impact of (modest) climate change on human history. By the spring, COVID-19 had reached all of our institutions, and we all grappled with a depressing new reality. As we transitioned to online teaching and those of us with children struggled with the absence of school or daycare, the pace of work slowed. It slowed, too, because I found the work more challenging than ever before. A key part of our process now involved interrogating our case studies more rigorously than before, and we soon found that many of those studies – including my own – suffered from precisely the problems we were attempting to identify and criticize. At first, this really troubled me. I sent question after annoying question to our co-authors, each of which, I’m sure, required extraordinary effort to answer. Not for the last time was I grateful for selecting such a remarkable team. While some scholars might have been affronted by my questions, all the answers I received were thoughtful and constructive. After a while, it dawned on me that this process of revision and interrogation could be an important part of the new research framework we hoped to advance – and a critical advantage of a consilient approach to climate history. We decided to be entirely upfront about the process, and in turn about how we were able to overcome the shortcomings that are all but inevitable in single-authored scholarship. We hoped that this expression of humility, as we saw it, would encourage other scholars to pursue the same approach. By early summer we had a complete draft. We now collaboratively undertook rounds of painstaking revisions to a Google Doc. As the weeks went by, we sharpened our arguments, excised unnecessary diversions, and crafted case studies that, we thought, convincingly considered causation and uncertainties. Everyone took part, and by the fall we were ready to submit. It was only when we received our peer reviews and Michael’s comments that I began to really believe that we might actually be able to publish in Nature. Still, our reviews did raise some criticisms that we needed to address. Using Lucidchart I created detailed tables, for example, that allowed us to visualize how we had interrogated each of our case studies, and a recent environmental history PhD and cartographer, Geoffrey Wallace, designed a crystal clear map to help readers interpret those tables. One big issue occupied me for nearly a week. A reviewer pointed out that we did not have a detailed definition of resilience, and wondered whether we even needed that term. Indeed “resilience” has become a loaded word in climate scholarship and discourse - and this requires a short digression. In 1973, ecologist Crawford Stanley Holling first imagined resilience as a capacity for ecosystems to “absorb change and disturbance” while maintaining the same essential characteristics. In a matter of years, scholars of natural hazards and climate change impacts appropriated and then modified the concept for their own purposes. Today, it is ubiquitous in the study of present and projected relationships between climate change and human affairs. Yet what it means exactly has not always been clear. Older definitions of the concept in climate-related fields privileged “bouncing back” in the wake of disaster, and were eventually criticized for assuming that all social change should be viewed negatively. Newer definitions can encompass change of such magnitude that all possible human responses to environmental disturbance could be classified as resilient – including collapse. The concept of resilience is also controversial for political reasons. Critics argue that a focus on resilience can carry with it the assumption that disasters are inevitable, and that it therefore normalizes and naturalizes the sources of vulnerability in populations. It can serve neoliberal ends, critics point out, by displacing the responsibility for avoiding disaster from governments to individuals. Since vulnerability is often the creation of unjust political and economic structures, the concept of resilience can obscure and thus support problematic power relations. Critics point out that normative uses of the concept can be used to denounce and “other” supposedly inferior – and typically non-western – ways of coping with disaster. Still, we decided that resilience was a term worth using. Only it and “adaptation” are terms that provide immediately recognizable and therefore accessible means of conceptualizing interactions between human communities and climate change that are different from, and often more complex than, those that can be characterized as disastrous. We decided that recent scholarship had moved beyond using the concept narrowly; in fact the IPCC now incorporates active adaptation within its understanding of resilience. We concluded that if we were careful to precisely define how we were using the term, and if we emphasized how resilience for some had come at the expense of others, then our use of resilience could allow us to more directly communicate to the general public – and to the policymaking community. In revisions it also became clear to us that many scholars who are not historians remain unfamiliar with the term “Climate History,” and associate it narrowly with the historical discipline. What we needed was a new term that, in the wake of our article, would unite scholars in every discipline that considered the social impacts of past climate change – and thereby encourage precisely the kind of consilient collaboration we call for. The term would need to communicate that this field was not another genre of the historical discipline - like environmental history - and it would need to stress our shared focus on the impacts of climate change on society. After we’d bounced around a number of options that seemed to privilege one discipline over another, Adam suggested “History of Climate and Society,” or HCS. We all agreed: this was a term that could work. Our article improved dramatically owing to the constructive suggestions of our editor and reviewers. Soon after we submitted our revisions, we learned to our delight that we’d been accepted for publication. Thanks to Adam, and with the support of press offices at Georgetown and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, we immediately started to plan a major effort to communicate our findings to the press, in at least five different languages. To some extent, this article is part of that effort, and I hope it expresses some of the key findings of an article that, we hope, will also be accessible to the general public. Yet climate historians – or rather, HCS scholars – are the most important audience for this piece. I hope it illuminates, first, what it's actually like to work in consilient teams that aim to publish in major scientific journals. Working in such teams will be foreign to many historians in particular, and it reminded me a great deal of what it's been like to establish, then direct, both this resource and the Climate History Network. It is a managerial task not so different from running a small company or NGO, and it exposed for me how, in interdisciplinary scholarship, the service and research components of academic life easily blend together. Most importantly, I hope this article communicates some of the benefits of working on a thoroughly interdisciplinary, consilient team. On many occasions my co-authors raised a point I wouldn’t have considered, corrected an argument I had intended to make, or warned me against using data that would have led us astray. Through discussions with our brilliant team, I learned far more while developing this project than I have while crafting any single-authored article. Teamwork was not always easy, and it was extraordinarily time consuming. Not all academic departments in every discipline will fully recognize its value. Yet I’m convinced that it is usually the best way to approach HCS projects. And now it gives me a tremendous feeling of satisfaction to know what our team accomplished together. Beyond these questions of process and method, it’s worth asking where HCS studies stand today. Certainly our article did not disprove that climate changes have had disastrous impacts on past societies – let alone that global warming has had, and will have, calamitous consequences for us. Archaeologists moreover have long considered the resilience of past populations, and some of our conclusions will not surprise many of them. Yet we hope that HCS scholars in all disciplines will now pay more attention to the diversity of past responses to climate change, including but no longer limited to those that were catastrophic. We also hope that our article will both discourage Doomist fears and inspire renewed urgency for present-day efforts at climate change adaptation. According to the Fourth National Climate Assessment, in the United States “few [adaptation] measures have been implemented and, those that have, appear to be incremental changes.” The story is similar elsewhere. Our study shows that the societies that survived and thrived amid the climatic pressures of the past were able to adapt to new environmental realities. Yet we also find that adaptation for some social groups could exacerbate the vulnerability of other groups to climate change. Our study therefore provides a wakeup call for policymakers. Not only is it critical for policymakers to quickly implement ambitious adaptation programs, but a key element of adaptation has to be reducing socioeconomic inequality. Adaptation, in other words, has to include efforts at environmental and social justice. That is, perhaps, the most important Little Ice Age lesson of all. Dagomar Degroot, Kevin Anchukaitis, Martin Bauch, Jakob Burnham, Fred Carnegy, Jianxin Cui, Kathryn de Luna, Piotr Guzowski, George Hambrecht, Heli Huhtamaa, Adam Izdebski, Katrin Kleemann, Emma Moesswilde, Naresh Neupane, Timothy Newfield, Qing Pei, Elena Xoplaki, Natale Zappia. “Towards a Rigorous Understanding of Societal Responses to Climate Change.” Nature (March, 2021). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03190-2.

0 Comments

|

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed