|

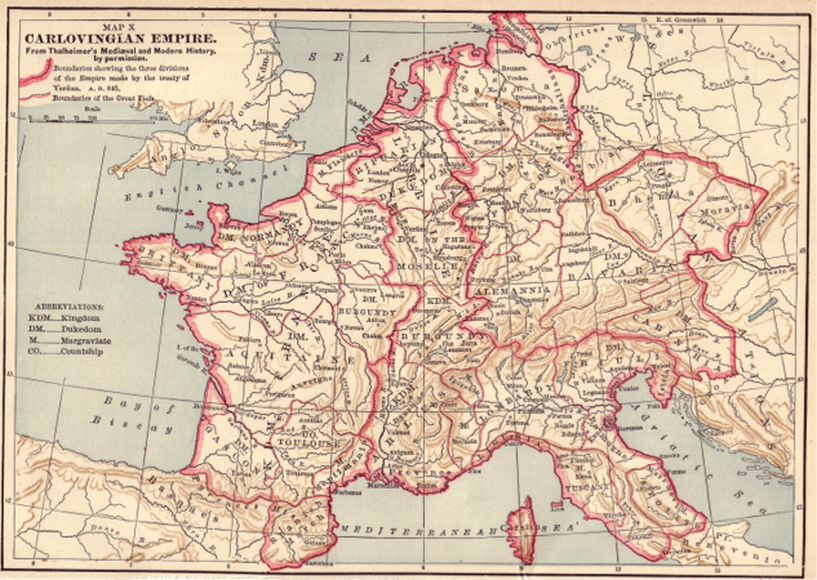

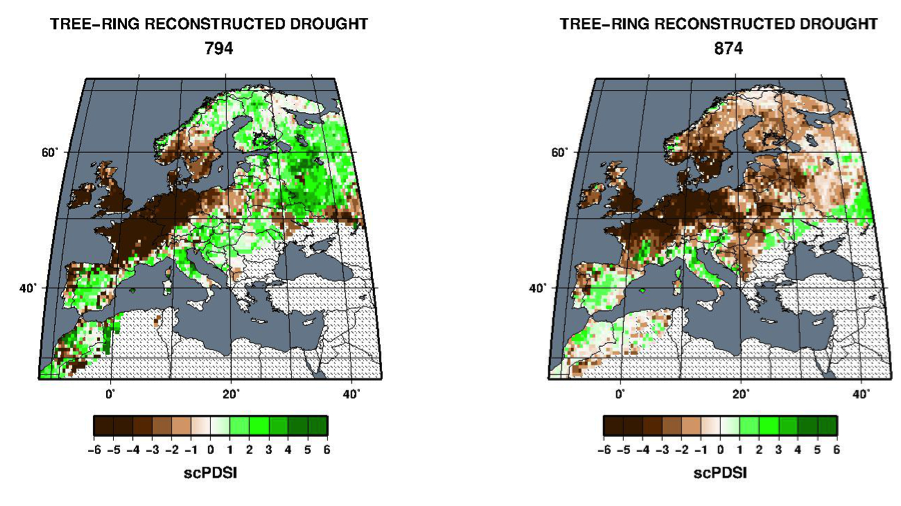

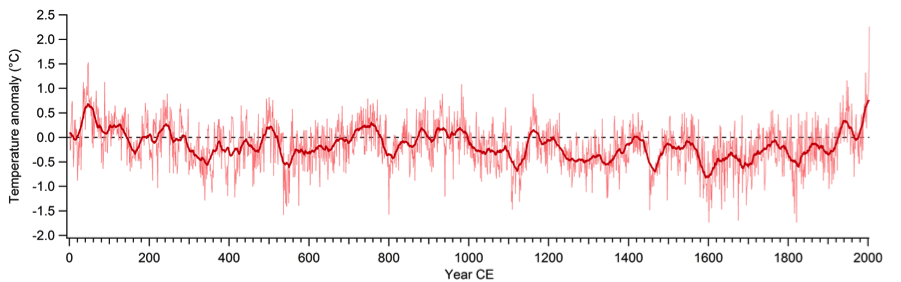

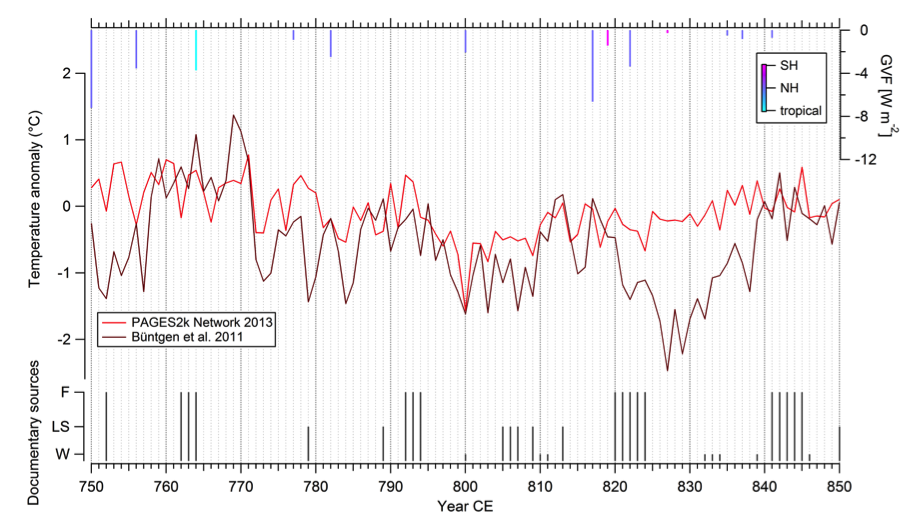

Dr. Tim Newfield, Princeton University, and Dr. Inga Labuhn, Lund University. Carolingian mass grave, Entrains-sur-Nohain, INRAP. Will climate change trigger widespread food shortages and result in huge excess mortality in our future? Many historians have argued that it has before. Anomalous weather, abrupt climate change, and extreme dearth often work together in articles and books on early medieval demography, economy and environment. Few historians of early medieval Europe would now doubt that severe winters, droughts and other weather extremes led to harvest failures and, through those failures, food shortages and mortality events. Most remaining doubters adhere to the idea that food shortages had causes internal to medieval societies. Instead of extreme weather or abrupt climate change, they blame accidents of (population) growth, deficient agrarian technology, unequal socioeconomic relations and weak institutions. Yet only rarely they have stolen the show or dominated the scholarship. For example, Amartya Sen’s “entitlement approach” to subsistence crises, which assigns primary importance to internal processes, has made few inroads in the literature on early medieval dearth, although in later periods it has many adherents. Of course, the idea that big events have a single cause – monocausality, in other words – rarely convinces historians for long. Famine theorists and historians of other eras and world regions now argue that neither external forces such as weather, nor internal forces such as entitlements, alone capture the complexity of food shortages. They propose that these two explanatory mechanisms, often labeled “exogenous” and “endogenous,” respectively, should not be considered independent of one another or mutually exclusive. To them, periods of dearth can be explained by environmental anomalies, like unusual and severe plant-damaging weather, that coincide with socioeconomic vulnerability and declining (for most people) entitlement to food. These explanations are more convincing. It seems that diverse factors acted in concert to cause, prolong and worsen food shortages. But proof for complex explanations for dearth in the distant past is hard to come by. Though they can be misleading, simpler, linear explanations are much easier to pull out of the extant evidence. This is true even when the sources are plentiful, as they are, at least by early medieval standards, for some regions and decades of Carolingian Europe. Food shortages in the Carolingian period, especially those that occurred during the reign of Charlemagne, have attracted the attention of scholars since the 1960s. Left: Bronze equestrian statuette of Charlemagne or possibly his grandson Charles the Bald (823-877). Discovered in Saint-Étienne de Metz and now in the Louvre. The figure is ninth century in date. The horse might be earlier and Byzantine. Charles the Bald ruled the western portion of the post-Verdun empire, although whether he was actually bald is still debated. Right: A Carolingian denarius (812-814) depicting Charlemagne. The Charlemagne of the Charlemagne reliquary mask (Center) is handsomer. The coin, though, is contemporary and the bust is from the mid fourteenth century. Housed in the Aachener Dom’s treasury, it contains a skullcap thought to be that of the emperor. For the Carolingian period, ordinances from the royal court, capitularies, reveal hoarding and speculation, and document official attempts to control the prices and movements of grain, while annalists and hagiographers recount severe winters and droughts. All of this evidence sheds light on dearth. Yet the legislative acts point to internal pressures on food supply, while the narrative sources highlight external ones. As we have seen, neither pressure adequately explains subsistence crises alone. Unfortunately, however, we rarely have evidence for endogenous and exogenous factors at the same time. Around the year 800, when Leo III crowned Charlemagne imperator, most evidence for dearth comes from the capitularies. Before and after, narrative evidence dominates. So Charlemagne’s food shortages appear to have had internal drivers, and Charles the Bald’s external ones. Or so the written sources lead us to believe. Carolingian Europe as of August 843 following the Treaty of Verdun. Under rex and imperator Charlemagne (742-814), Carolingian territory stretched to include the area of Europe outlined here. Fortunately, evidence from other disciplines allows historians to fill in some of the gaps. External pressures are easier to establish by turning to the palaeoclimatic sciences. Using them, we are beginning to rewrite the history of continental European dearth, weather and climate from 750 to 950 CE. We are working on a new study that combines a near-exhaustive assessment of Carolingian written evidence for subsistence crises and weather with scientific evidence for changes in average temperature, precipitation, and volcanic activity (which can influence climate). We are trying to answer some big questions, such as: What role did droughts, hard winters and extended periods of heavy rainfall have in sparking, prolonging or worsening Carolingian food shortages? Were these external forces the classic triggers of dearth that many early medievalists think they were? Indicators of past climate embedded in trees and ice can test and corroborate observations of anomalous temperature and precipitation. For instance, the droughts of 794 and 874 CE, documented respectively in the Annales Mosellani and Annales Bertiniani, show up in the tree ring-based Old World Drought Atlas (OWDA, see below). Additionally, as McCormick, Dutton and Mayewski demonstrated, multiple severe Carolingian winters also align fairly neatly with atmosphere-clouding Northern Hemisphere volcanism reconstructed using the GISP2 Greenlandic ice core. The Old World Drought Atlas (OWDA) for 794 and 874. Negative values indicate dry conditions, positive values indicate wet conditions (from Cook et al. 2015). By marrying written and natural archives, we are able to perfect our appreciation of the scale and extent of the weather extremes that coincide with Carolingian periods of dearth. Yet instead of simply providing answers, our integrated data are raising questions, and pushing us towards a messier history of early medieval food shortage. This is because the independent lines of evidence often do not agree. For example, only two of the 15 driest years between 750 and 950 CE in the OWDA coincide with drought in Carolingian sources. Admittedly, some of this dissonance may be artificial. The written record for weather and dearth is incomplete. To be sure, some places and times during the Carolingian era, broadly defined as it is here, are poorly documented. So reported drought years can appear kind of wet in the tree-based OWDA in some Carolingian regions (parts of northern Italy and Provence in 794 and 874 for instance). Moreover, the detailed or “high-resolution” palaeoclimatology available now for early medieval Europe is much better for some regions than others. Tree-ring series extending back to 750 presently exist for few European regions. It is simply not possible to precisely pair some reported weather extremes or dearths to palaeoclimate reconstructions. Indeed, spatially the two lines of evidence can be mismatched. They can also be seasonally inconsistent, as the trees tell us far less about temperature and precipitation in the winter than they do for the summer. Matches between historical and scientific evidence are therefore generally limited to the growing seasons, in places where written sources and palaeoclimate data overlap. That is enough to yield some surprising results. When the written record is densest, there is natural evidence for severe weather and rapid climate change, but not for food shortages. Take the dramatic drop in average temperatures registered in European trees at the opening of the ninth century. According to the 2013 PAGES 2K Network European temperature reconstruction, temperatures were cooler around the time of Charlemagne’s coronation than they had been at any time between the mid sixth and early eleventh centuries. This dramatic cooling aligns well with a relatively small Northern Hemisphere volcanic eruption, detected in the recent ice-core record of volcanism led by Sigl. The eruption would have ejected sunlight-scattering sulfur aerosols into the atmosphere. Notably, larger events in the Carolingian era, like those of 750, 817 and 822, clearly had less of an influence on European temperature. The cold of 800 is equally pronounced but less unusual in a tree-based temperature reconstruction from the Alps. In this series, the late 820s are remarkably cooler. Documentary sources register the falling temperatures. The Carolingian Annales regni francorum report severe growing-season frosts (aspera pruina) in 800. The Irish Annals of Ulster document a difficult and mortal winter in an entry quite possibly misdated in the Hennessy edition at 798 (799 or the 799/800 winter is more likely). Yet surprisingly, there is no contemporary record of food shortages in Europe. Top: European Temperature Reconstruction, 0-2000 CE (data from Pages 2K Consortium, 2013). Bottom: Middle Red: PAGES 2K 2013 Consortium European temperatures; Middle Burgundy: Büntgen et al 2011 Alpine temperature reconstruction; Top: Sigl et al 2015 ice-core record of Global Volcanic Forcing (GVF); Bottom: Written evidence for food shortages, both famines (F) and lesser shortages (LS). ‘W’ indicates no evidence for dearth but evidence for extreme weather. Between 750 and 950 we have identified 23 food shortages: 12 spatially and temporally circumscribed lesser shortages and 11 large multi-year famines. Scholars tend to focus on instances when the written evidence for dearth and the natural evidence for anomalous weather align tidily. It seems that just as often, however, the two lines of evidence do not match so neatly. Severe weather may not always have triggered dearth in the early Middle Ages. Contemporary peoples could apparently cope with weather extremes in ways that allowed them to escape food shortages. Early medieval vulnerability to external forces of dearth seems to have varied over space and time. We need to investigate the contrasting abilities of peoples from different early medieval regions and subperiods, participating in distinct agricultural economies with their own agrarian technologies, to withstand plant-damaging environmental extremes. Several studies already suggest early medievals were capable of responding to gradual climate change. But to argue that they were not rigid or helpless when faced with marked seasonal temperature or precipitation anomalies, we must first identify, from sparse sources, potential moments of resilience. In this we run the risk of reading too much into absences of evidence. Yet the conclusion seems inescapable: when written sources are relatively abundant and there is no record of dearth during notable deviations in temperature and precipitation, early medievals must have adapted successfully. Going forward, we must identify both moments and mechanisms of early medieval resilience in the face of climate change. Teasing these out from diverse sources might be tough going, but these elements are missing from the history of early medieval dearth and climate. Their omission has allowed for misleadingly neat histories of climate change and disaster in the period. Similar problems might well plague other histories that too clearly link climate changes to food shortages and mortality crises. Research that complicates these links could offer compelling new insights about our warmer future. Authors' note: this is a short sampling of a much longer and more detailed multidisciplinary examination of Carolingian dearth, weather and climate, currently in preparation. Select Reading:

P. Bonnassie, “Consommation d’aliments immondes et cannibalisme de survie dans l’Occident du Haut Moyen Âge” Annales: Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations 44 (1989), pp. 1035-1056. U. Büntgen et al, “2,500 Years of European Climate Variability and Human Susceptibility” Science 331 (2011), pp. 578-582. U. Büntgen and W. Tegel, “European Tree-Ring Data and the Medieval Climate Anomaly” PAGES News 19 (2011), pp. 14-15. F. Cheyette, “The Disappearance of the Ancient Landscape and the Climatic Anomaly of the Early Middle Ages: A Question to be Pursued” Early Medieval Europe 16 (2008), pp. 127-165. E. Cook et al, “Old World Megadroughts and Pluvials during the Common Era” Science Advances 1 (2015), e1500561. S. Devereux, Theories of Famine (Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1993). R. Doehaerd, Le Haut Moyen Âge occidental: Economies et sociétés (Nouvelle Clio, 1971). P.E. Dutton, “Charlemagne’s Mustache” and “Thunder and Hail over the Carolingian Countryside” in his Charlemagne’s Mustache and Other Cultural Clusters of a Dark Age (Palgrave, 2004), pp. 3-42, 169-188. M. McCormick, P.E. Dutton and P. Mayewski, “Volcanoes and the Climate Forcing of Carolingian Europe, A.D. 750-950” Speculum 82 (2007), pp. 865-895. T. Newfield, “The Contours, Frequency and Causation of Subsistence Crises in Carolingian Europe (750-950)” in P. Benito i Monclús ed., Crisis alimentarias en la edad media: Modelos, explicaciones y representaciones (Editorial Milenio, 2013), pp. 117-172. PAGES 2k Network, “Continental-Scale Temperature Variability during the Past Two Millennia” Nature Geoscience 6 (2013), pp. 339-346. K. Pearson, “Nutrition and the Early Medieval Diet” Speculum 72 (1997), pp. 1-32. A. Sen, Poverty and Entitlements: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation (Oxford University Press, 1981). M. Sigl et al, “Timing and Climate Forcing of Volcanic Eruptions for the Past 2,500 Years” Nature 523 (2015), pp. 543-549. P. Slavin, “Climate and Famines: A Historical Reassessment” WIREs Climate Change 7 (2016), pp. 433-447. A. Verhulst, “Karolingische Agrarpolitik: Das Capitulare de Villis und die hungersnöte von 792/793 und 805/806” Zeitschrift fur Agrargeschichte und Agrarsoziologie 13 (1965), pp. 175-189. |

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed