|

Prof. María Cristina García, Cornell University. People displaced by extreme weather events and slower-developing environmental disasters are often called “climate refugees,” a term popularized by journalists and humanitarian advocates over the past decade. The term “refugee,” however, has a very precise meaning in US and international law and that definition limits those who can be admitted as refugees and asylees. Calling someone a “refugee” does not mean that they will be legally recognized as such and offered humanitarian protection. The principal instruments of international refugee law are the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, which defined a refugee as: "any person who owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it." [i] This definition, on which current U.S. law is based, does not include any reference to the “environment,” “climate,” or “natural disaster,” that might allow consideration of those displaced by extreme weather events and/or climate change. In some regions of the world, other legal instruments have supplemented the U.N. Refugee Convention and Protocol, and these instruments offer more expansive definitions of refugee status that might offer protections to the environmentally displaced. The Organization of African Unity’s “Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa (1969)” includes not only external aggression, occupation, and foreign domination as the motivating factors for seeking refuge, but also “events seriously disturbing the public order.”[ii] In the Americas, the non-binding Cartagena Declaration on Refugees (1984), crafted in response to the wars in Central America, set regional standards for providing assistance not just for those displaced by civil and political unrest but also those fleeing “circumstances which have seriously disturbed the public order.”[iii] The Organization of American States has also passed a series of resolutions offering member states additional guidance on how to respond to refugees, asylum seekers, stateless persons, and others in need of temporary or permanent protection. In Europe, the European Union Council Directive (2004) has identified the minimum standards for the qualification and status of refugees or those who might need “subsidiary protection.”[iv] Together, these regional and international conventions, protocols, and guidelines acknowledge that people are displaced for a wide range of reasons and that they deserve respect and compassion and, at the bare minimum, temporary accommodation. Climate change has been absent in these discussions perhaps because environmental disruptions such as hurricanes, earthquakes, and drought were long assumed to be part of the “natural” order of life, unlike war and civil unrest, which are considered extraordinary, man-made, and thus avoidable. The expanding awareness that societies are accelerating climate change to life-threatening levels requires that countries reevaluate the populations they prioritize for assistance, and adjust their immigration, refugee, and asylum policies accordingly. Under current U.S. immigration law, those displaced by sudden-onset disasters and environmental degradation do not qualify for refugee status or asylum unless they are able to demonstrate that they have also been persecuted on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. This wasn’t always the case: indeed, U.S. refugee policy once recognized that those displaced by “natural calamity” were vulnerable and deserved protection. The 1953 Refugee Relief Act, for example, defined a refugee as “any person in a country or area which is neither Communist nor Communist-dominated, who because of persecution, fear of persecution, natural calamity or military operations is out of his usual place of abode and unable to return thereto… and who is in urgent need of assistance for the essentials of life or for transportation.”[v] The 1965 Immigration Act (Hart-Celler Act) established a visa category for refugees that included persons “uprooted by catastrophic natural calamity as defined by the President who are unable to return to their usual place of abode.” [vi] Between 1965 and 1980, no refugees were admitted to the United States under the “catastrophic natural calamity” provision but that did not stop legislators from opposing its inclusion in the refugee definition. Some legislators argued that it was inappropriate to offer permanent resettlement to people who were only temporarily displaced; while others took issue on the grounds that it undermined the economic recovery of hard-hit countries by draining them of their most highly-skilled citizens. The 1980 Refugee Act subsequently eliminated any reference to natural calamity or disaster, in line with the United Nation’s definition of refugee status. In recent decades, scholars, advocates, and policymakers have called for a reevaluation of the refugee definition in order to grant temporary or permanent protection to a wider range of vulnerable populations, including those displaced by environmental conditions. At present, U.S. immigration law offers very few avenues for entry for the so-called “climate refugees”: options are limited to Temporary Protected Status (TPS), Delayed Enforced Departure (DED), and Humanitarian Parole. The 1990 Immigration Act provided the statutory provision for TPS: according to the law, those unable to return to their countries of origin because of an ongoing armed conflict, environmental disaster, or “extraordinary and temporary conditions” can, under some conditions, remain and work in the United States until the Attorney General (after 2003, the Secretary of Homeland Security) determines that it is safe to return home. [vii] There is one catch: in order to qualify for TPS one already has to be physically present in the United States—as a tourist, student, business executive, contract worker or even as an unauthorized worker. TPS is granted on a 6, 12, or 18-month basis, renewed by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) if the qualifying conditions persists. TPS recipients do not qualify for state or federal welfare assistance but they are allowed to live and work in the United States until federal authorities determine that it’s safe to return. In the meantime, they can send much-needed remittances to their families and communities back home to assist in their recovery. TPS is one way, albeit imperfect, that United States exercises its humanitarian obligations to those displaced by environmental disasters and climate change. It is based on the understanding that countries in crisis require time to recover; if nationals living abroad return in large numbers, in a short period of time, they can have a destabilizing effect that disrupts that recovery. Countries affected by disaster must meet certain conditions in order to qualify: first, the Secretary of Homeland Security must determine that there has been a substantial disruption in living conditions as a result of a natural or environmental disaster, making it impossible for a government to accommodate the return of its nationals; and second, the country affected by environmental disaster must officially petition for its nationals to receive TPS status (a requirement that is not imposed on countries affected by political violence). However, environmental disaster does not automatically guarantee that a country’s nationals will receive temporary protection. The U.S. federal government has total discretion and the decision-making process is not immune to domestic politics. Deferred Enforced Departure (DED) is another status available to those unable to return to hard-hit areas: DED offers a stay of removal as well as employment authorization, but the status is most often used when TPS has expired. In such circumstances, the president has the discretionary (but rarely used) authority to allow nationals to remain in the United States in the interest of humanitarian or foreign policy, or until Congress can pass a law that offers a permanent accommodation. [viii] Humanitarian “parole” is yet another recourse for the environmentally displaced. The 1952 McCarran Walter Act granted the attorney general discretionary authority to grant temporary entry to individuals, on a case-by-case basis, if deemed in the national interest. Since 2002, humanitarian parole requests have been handled by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), and are granted much more sparingly than during the Cold War. USCIS generally grants parole only for one year (renewable on a case-by-case basis). [ix] Parole does not place an individual on a path to permanent residency or citizenship, nor does it make applicants eligible for welfare benefits; only occasionally are “parolees” granted the right to work, allowing them to earn a livelihood and send remittances to communities hard hit by political and environmental disruptions. TPS, DED, and humanitarian parole are only temporary accommodations for select and small groups of people. They are an inadequate response to the humanitarian crisis that will develop in the decades to come. Scientists forecast that in an era of unmitigated and accelerated climate change, sudden-onset disasters will become fiercer, exacerbating poverty, inequality, and weak governance, and forcing many more people to seek safe haven elsewhere—perhaps in the hundreds of millions over the next half-century. In the current political climate, it’s hard to imagine that wealthier nations like the United States will open their doors to even a tiny fraction of these displaced peoples; however, the more economically developed countries must do more to honor their international commitments to provide refuge, especially to those in developing areas who are suffering from environmental conditions they did not create. In the decades to come, as legislators try to mitigate the effects of climate change and help their populations become resilient, they must also share the burden of a human displacement caused by the failure to act quickly enough. María Cristina García, an Andrew Carnegie Fellow, is the Howard A. Newman Professor of American Studies in the Department of History at Cornell University. She is the author of several books on immigration, refugee, and asylum policy. She is currently completing a book on the environmental roots of refugee migrations in the Americas. [i] United Nations, “Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees,” 14, http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/3b66c2aa10. The 1951 Convention limited the focus of assistance to European refugees in the aftermath of the Second World War. The 1967 Protocol removed these temporal and geographic restrictions. The United States did not sign the 1951 Convention but it did sign the 1967 Protocol.

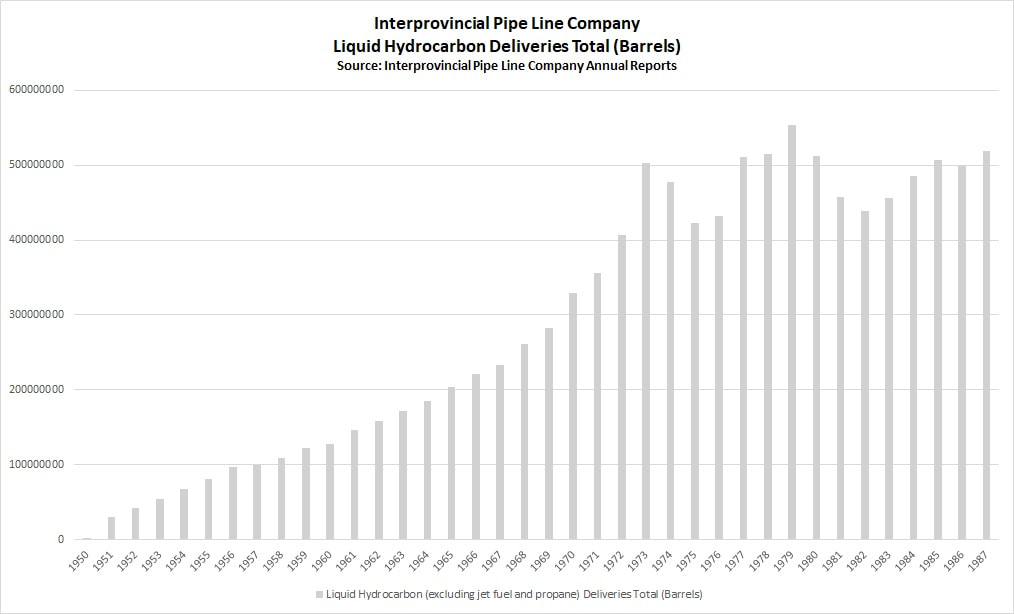

[ii] The OAU convention stated that the term refugee should also apply to “every person who, owing to external aggression, occupation, foreign domination or events seriously disturbing the public order in either part or the whole of his country or origin or nationality, is compelled to leave his place of habitual residence in order to seek refuge in another place outside his country of origin or nationality.” Organization of African Unity, Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa,” http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/about-us/background/45dc1a682/oau-convention-governing-specific-aspects-refugee-problems-africa-adopted.html accessed September 15, 2017. [iii] The Cartagena Declaration stated that “in addition to containing elements of the 1951 Convention…[the definition] includes among refugees, persons who have fled their country because their lives, safety or freedom have been threatened by generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violations of human rights or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed the public order.” Cartagena Declaration on Refugees,” http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/about-us/background/45dc19084/cartagena-declaration-refugees-adopted-colloquium-international-protection.html [iv] European Union, “Council Directive 2004/83/EC,” April 29, 2004, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32004L0083 accessed March 20, 2018. [v] Refugee Relief Act of 1953 (P.L. 83-203), https://www.law.cornell.edu/topn/refugee_relief_act_of_1953. [vi] Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (P.L. 89-236), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-79/pdf/STATUTE-79-Pg911.pdf [vii] Immigration Act of 1990 (P.L.101-649), https://www.congress.gov/bill/101st-congress/senate-bill/358 [viii] USCIS, “Deferred Enforced Departure,” https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/temporary-protected-status/deferred-enforced-departure. [ix] The humanitarian parole authority was first recognized in the 1952 Immigration Act (more popularly known as the McCarran Walter Act). See http://library.uwb.edu/Static/USimmigration/1952_immigration_and_nationality_act.html. See also “§ Sec. 212.5 Parole of aliens into the United States,” https://www.uscis.gov/ilink/docView/SLB/HTML/SLB/0-0-0-1/0-0-0-11261/0-0-0-15905/0-0-0-16404.html Prof. Sean Kheraj, York University. This is the fifth post in a collaborative series titled “Environmental Historians Debate: Can Nuclear Power Solve Climate Change?” hosted by the Network in Canadian History & Environment, the Climate History Network, and ActiveHistory.ca. If nuclear power is to be used as a stop-gap or transitional technology for the de-carbonization of industrial economies, what comes next? Energy history could offer new ways of imagining different energy futures. Current scholarship, unfortunately, mostly offers linear narratives of growth toward the development of high-energy economies, leaving little room to imagine low-energy futures. As a result, energy historians have rarely presented plausible ideas for low-energy futures and instead dwell on apocalyptic visions of poverty and the loss of precious, ill-defined “standards of living.” The fossil fuel-based energy systems that wealthy, industrialized nation states developed in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries now threaten the habitability of the Earth for all people. Global warming lies at the heart of the debate over future energy transitions. While Nancy Langston makes a strong case for thinking about the use of nuclear power as a tool for addressing the immediate emergency of carbon pollution of the atmosphere, her arguments left me wondering what energy futures will look like after de-carbonization. Will industrialized economies continue with unconstrained growth in energy consumption, expand reliance on nuclear power, and press forward with new technological innovations to consume even more energy (Thorium reactors? Fusion reactors? Dilithium crystals?)? Or will profligate energy consumers finally lift their heads up from an empty trough and start to think about ways of living with less energy? Unfortunately, energy history has not been helpful in imagining low-energy possibilities. For the past couple of years, I’ve been getting familiar with the field of energy history and, for the most part, it has been the story of more. [1] Energy history is a related field to environmental history, but also incorporates economic history, the history of capitalism, social history, cultural history and gender history (and probably more than that). My particular interest is in the history of hydrocarbons, but I’ve tried to take a wide view of the field and consider scholarship that examines energy history in deeper historical contexts. There are several scholars who have written such books that consider the history of human energy use in deep time. For example, in 1982, Rolf Peter Sieferle started his long view of energy history in The Subterranean Forest: Energy Systems and the Industrial Revolution by considering Paleolithic societies. Alfred Crosby’s Children of the Sun: A History of Humanity’s Unappeasable Appetite for Energy (2006) begins its survey of human energy history with the advent of anthropogenic fire and its use in cooking. Vaclav Smil goes back to so-called “pre-history” at the start of Energy and Civilization: A History (2017) to consider the origins of crop cultivation. In each of these surveys energy historians track the general trend of growing energy use. While they show some dips in consumption and global regional variation, the story they tell is precisely as Crosby puts it in his subtitle, a tale of humanity’s unappeasable appetite for greater and greater quantities of energy. The narrative of energy history in the scholarship is remarkably linear, verging on Malthusian. According to Smil: “Civilization’s advances can be seen as a quest for higher energy use required to produce increased food harvests, to mobilize a greater output and variety of materials, to produce more, and more diverse, goods, to enable higher mobility, and to create access to a virtually unlimited amount of information. These accomplishments have resulted in larger populations organized with greater social complexity into nation-states and supranational collectives, and enjoying a higher quality of life.” [2] Indeed, from a statistical point of view, it’s difficult not to reach the conclusion that humans have proceeded inexorably from one technological innovation to another, finding more ways of wrenching power from the Sun and Earth. The only interruptions along humanity’s path to high-energy civilization were war, famine, economic crisis, and environmental collapse. Canada’s relatively short energy history appears to tell a similar story. As Richard W. Unger wrote in The Otter~la loutre recently, “Canadians are among the greatest consumers of energy per person in the world.” And the history of energy consumption in Canada since Confederation shows steady growth and sudden acceleration with the advent of mass hydrocarbon consumption between the 1950s and 1970s. Steve Penfold’s analysis of Canadian liquid petroleum use focuses on this period of extraordinary, nearly uninterrupted growth in energy consumption. Only in 1979 did Canadian petroleum consumption momentarily dip in response to an economic recession. “What could have been an energy reckoning…” Penfold writes, “ultimately confirmed the long history of rising demand.” [2] I’ve seen much of what Penfold finds in my own research on the history of oil pipeline development in Canada. Take, for instance, the Interprovincial pipeline system, Canada’s largest oil delivery system. For much of Canada’s “Great Acceleration” the history of more couldn’t be clearer: This view of energy history as the history of more informs some of the conclusions (and predictions) of energy historians. Crosby is, perhaps, the most optimistic about the potential of technological innovation to resolve what he describes as humanity’s unsustainable use of fossil fuels. In Crosby’s view, “the nuclear reactor waits at our elbow like a superb butler.” [4] For the most part, he is dismissive of energy conservation or radical reductions in energy consumption as alternatives to modern energy systems, which he admits are “new, abnormal, and unsustainable.” [5] Instead, he foresees yet another technological revolution as the pathway forward, carrying on with humanity’s seemingly endless growth in energy use. Energy historians, much like historians of the Anthropocene, have a habit of generalizing humanity in their analysis of environmental change. As I wrote last year in The Otter~la loutre, “To understand the history of Canada’s Anthropocene, we must be able to explain who exactly constitutes the “anthropos.”” Energy historians might consider doing the same. The history of human energy use appears to be a story of more when human energy use is considered in an undifferentiated manner. The pace of energy consumption in Canada, for instance, might look different when considering the rich and the poor, settlers and Indigenous people, rural Canadians and urban Canadians. Globally, energy histories around the world tell different stories beyond the history of more including histories of low-energy societies and histories of energy decline. Most global energy histories focus on industrialized societies and say little about developing nations and the persistence of low-energy, subsistence economies. If Smil is correct and “Indeed, higher energy use by itself does not guarantee anything except greater environmental burdens,” then future decisions about energy use should probably consider lower energy options. [6] Transitioning away from burning fossil fuels by using nuclear power may alleviate the immediate existential crisis of global warming, but confronting the environmental implications of high-energy societies may be the bigger challenge. To address that challenge, we may need to look back at histories of less. Sean Kheraj is the director of the Network in Canadian History and Environment. He’s an associate professor in the Department of History at York University. His research and teaching focuses on environmental and Canadian history. He is also the host and producer of Nature’s Past, NiCHE’s audio podcast series and he blogs at http://seankheraj.com. [1] I’m borrowing from Steve Penfold’s pointed summary of the history of gasoline consumption in Canada: “Indeed, at one level of approximation, you could reduce the entire his-tory of Canadian gasoline to a single keyword: more.” See Steve Penfold, “Petroleum Liquids” in Powering Up Canada: A History of Power, Fuel, and Energy from 1600 ed. R. W. Sandwell (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016), 277.

[2] Vaclav Smil, Energy and Civilization: A History (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2017), 385. [3] Penfold, “Petroleum Liquids,” 278. [4] Alfred W. Crosby, Children of the Sun: A History of Humanity’s Unappeasable Appetite for Energy (New York: W.W. Norton, 2006), 126. [5] Ibid, 164. [6] Smil, Energy and Civilization, 439. |

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed