|

This is the fifth post in the series Historians Confront the Climate Emergency, hosted by ActiveHistory.ca, NiCHE (Network in Canadian History & Environment), Historical Climatology, and Climate History Network. Dr. Barbara Leckie, Carleton University The rhetoric of warning, emergency, and alarm is everywhere in climate change coverage. Headlines flag the recent release of the IPCC-1 as our “starkest warning yet,”[1] cities and institutions around the world announce climate emergencies, and academic studies draw on the metaphor of the fire alarm in an effort to convey the urgency of the crisis.[2] As different as each of these registers are, they all invest in the view that warnings are not idle but activating: that they will do something. Greta Thunberg is perhaps the best-known public commentator to combine all three of these rhetorical terms—warning, emergency, and alarm—in her many calls for climate action. Consider her speech to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland on 25 January 2019 in which she focuses on the latter, the fire alarm. “Our house is on fire. I am here to say, our house is on fire.” In the conclusion to her speech, she returns to the metaphor of the house on fire: “I want you to act as if our house is on fire. Because it is.” I agree that the climate crisis is an emergency. I agree with the warnings and alarms. But I also wonder if there is a saturation point on climate warnings and alarms? And, worse, I wonder if they might thwart the very action for which they advocate. To be sure, immediate and sustained climate action is necessary and it has never been more urgent than now. News media have translated the science into terms that gain the attention of a general reading public. And Thunberg’s mobilization of phrases like “our house is on fire” have catalyzed action, contributed to a worldwide youth movement focused on climate action, and inspired global movements like Extinction Rebellion. They’ve also given ballast to the Green New Deal and related proposals for a green economy less wedded to sustainability discourses. One would be hard-pressed to say that her rhetoric of warning, emergency, alarm, and warning has had no impact. But has this rhetoric had other, less inspiring, impacts as well? Consider J. L. Austin’s work on speech act theory. His elaboration of the warning as a performative—a speech act that performs what it says—in How to Do Things with Words maintains that warnings need to meet three requirements: they should signal an immediate danger, they should be plausible, and there should be clear protocols for action.[3] Although most climate warnings meet the first two requirements, many do not meet the last requirement. Because there are few clear protocols for climate action on individual, local, national, global, or planetary scales, the alarm is sounded but often those who heed the alarm are not sure what to do next. There’s a clear sequence for the house on fire scenario: the alarm rings, the inhabitants of the house are alerted, they leave the house, they call the fire department. But how does this metaphor translate for climate action? Not well. To be sure, the alarms may be rung, and people may even leave the real or figurative house (an endangered territory or region or, in some cases, country). But who exactly is the fire department? Is it the government? Corporations? Individuals? The IPCC? Indigenous elders? Policy makers? All of the above?[4] There are lots of impassioned views on where to turn but little agreement. Two things are clear however: there has been no effective resolution thus far; and given that we have only a decade to act decisively, it is highly unlikely that these debates will be resolved in way that yields effective action in that time. We have been warned about the climate crisis, the alarm bells have been ringing for decades, but carbon emissions continue to rise (even with the significant slowing down of the economy during Covid).[5] So, too, do racial and economic injustices, to which the climate crisis is inextricably bound. And so, while warnings have been effective in some ways, they have not been effective in the ways that are most necessary. In fact, they may be counterproductive. They may be bolstering the very neoliberal economy that many climate thinkers hold responsible for preventing action on the climate crisis in the first place. The alarms instill fear. And fear is a powerful vector through which neoliberalism operates. It enables, as we saw in the wake of 9/11, the passing of bills and waging of wars that would otherwise be met with greater resistance and dissent. It enables, as we saw then and continue to see now, the introduction of surveillance systems, the limiting of certain freedoms and the exercise of others, and it provides the rationale for a whole set of regulations, loosenings, and austerity claims that would have been unimaginable without the alarm. The alarms, in short, terrify. When we feel “under tension,” the actions we most desire are those that will reassure us that we should not be afraid, actions that contradict the alarm, throwing its very validity into question. If we are, as a society, investing in oil companies, for example, and bailing them out in the pandemic, then surely the climate crisis is not as bad as we think. If our friends are flying and living as they usually do and, importantly, if we do too, then surely the calls to alarm are not merited. For as Bruno Latour notes, climate projections are descriptions (constatives) that are also warnings (performatives). The problem is that because they do not dictate specific actions adequate to the climate predicament (and, I would argue cannot), we seek solace elsewhere. It is a situation designed to make us all climate deniers for the welcome relief that such denial brings.[6] We want to believe that those projections do not mean what they seem to mean. What is the alternative? Here I find Walter Benjamin’s commentary on the rhetoric of the fire alarm in the interwar years helpful. It offers insight into both why warnings to date have been unsuccessful and how, inflected differently, they might succeed. In the years leading up to the Second World War, Benjamin presciently remarks that the continuous alarm is the catastrophe. What is needed in its place, he argues, is not the state of emergency that a constant ringing of the alarm registers but rather a “real state of emergency” spurred by what he calls “interruption.”[7] Alarms, warnings, and emergencies should interrupt our lives. They should ask us to stop what we’re doing and to respond to the alarm. In the absence of a clear course of action, what might it mean to hold open the interruption? Benjamin’s call for interruption, variously defined, is tricky precisely because it is performed. Its performance resists representation in language just as it also resists the temporal models to which we’re often accustomed in the Global North (and, notably, on which the alarm relies).[8] Benjamin’s rethinking of temporality in tandem with his materialist history draws out a point that anatomies of alarm often neglect: the privileging of interruption as a critical mode to address social and political crisis. In doing so, Benjamin divides the potential work of the alarm between a call to action, an anxious awareness of danger (being “under tension,” panicking, the ongoing emergency), and a real state of emergency. The real state of emergency interrupts all of these definitions by interrupting the structure through which they are understood and instead locates action in forms of response that reconfigure existing temporal models in new ways. Let’s return to Thunberg’s remarks cited above: “I want you to act as if our house is on fire. Because it is.” Between the “as if” and the “it is” Thunberg captures the cognitive dissonance experienced by so many living in the Global North today. The climate emergency feels unreal (“as if”) and yet most of us also know the emergency is real (“it is”). Climate warnings uphold a linear timeline that cannot comprehend this sort of dissonance. The warning interrupts the line but instead of being an opening for confronting the crisis, it doubles down on the line and intensifies the emergency (that continuous alarm I referred to above). Benjamin, by contrast, mobilizes the warning to hold together performative contradictions—the “as if” and “it is”—and to create a space for thinking, as he puts it, “quite otherwise”.[9] What this quite otherwise might look like in the days and years to come is for all of us to envision and realize. Doing so, however, will involve a departure from the very temporal structure that the previous sentence, and this post overall, upholds; it will involve a honing in, instead, on a now constellated with co-written and open possibilities that will, in changing the time, change our times. Barbara Leckie is Professor in the Department of English and the Institute for the Comparative Study of Literature, Art, and Culture at Carleton University, Ottawa. She is the author of Open Houses: Poverty, the Architectural Idea, and the Novel in Nineteenth-Century Britain (2018) among other books and articles. She is the editor of Sanitary Reform in Victorian Britain: End of Century Assessments and New Directions (2013); and co-editor, with Janice Schroeder, of an abridged edition of Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor (2020). She writes often on climate change and the humanities and is the founder and co-ordinator of the Carleton Climate Commons. [1] There are similar headlines referencing warning in CBC, CNBC, and The Economist. But when one turns to the Report itself, there are no deafening by alarm bells. Indeed, in its 4,000 pages, the word alarm is used only twice, emergency four times (once in a citation and three times in the bibliography), and the word warning thirty-one times (none of which, notably, suggest that the Report itself is a warning. In the case of warning, the references are to either heat warnings or early warning systems and, as noted, none issue an overall call to warning. Over half of these references, moreover, are in the bibliography.

[2] See Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything and On Fire: The Burning Case for a Green New Deal, Andreas Malm’s Fossil Capital and The Progress of This Storm, and Bruno Latour’s Facing Gaia to name only a few. [3] J.L Austin, How To Do Things with Words (New York: Oxford University Press, 1962). [4] In response to the IPCC Report, Frank Van Gasbeke notes the following in Forbes: “And yet, the unprecedented IPCC mayday call is nowhere met with a state of emergency declaration. Not in the US nor anywhere else. The paradox is that the threat of quality and loss of life is higher now than it was for any war or plague in history.” The article that follows details one of the few elaborations, albeit brief, of what a declaration of world emergency could set in motion. He concludes, “In essence, a state of emergency would not only constitute a significant act of care to avoid a crime against humanity. It would be a formidable initiative to reclaim global leadership with ensuing benefits for new technologies and industries, including a new standard-setting for quality of life.” Vas Gasbeke imagines a response commensurate to the emergency. What I am outlining in this short post, by contrast, are the calls to emergency and alarm that, in the absence of action, mute the credibility of the alarm system without at the same time muting the danger to which the alarm points. [5] In an interview with Julian Brave NoiseCat, Katy Lederer comments: “I read that the Yale Program on Climate Change put out a poll saying that the number of Americans who are “alarmed” about climate change has doubled in the last five years, to 24 percent. But it doesn’t always feel like being alarmed really makes much difference as a political actor.” [6] See Jonathan Safran Foer for a discussion of his own climate denial, Kari Marie Norgaard for a discussion of its impact on a Scandinavian community, and Allen MacDuffie for an excellent pre-history to this structure of denial in the nineteenth century. [7] Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” Illuminations, translated by Harry Zohn (Harcourt, 1968), 257. [8] Many Indigenous views also convey richly layered temporal models that depart from the default linearity of the Global North. See, for example, Nick Estes, Robin Kimmerer, and Kyle Whyte among others. My point in this brief post is not to single out only one possibility for the articulation of new temporal modes, but rather to recommend the multiplication of possibilities. I offer Benjamin’s work, accordingly, as one example among others. [9] Walter, Benjamin, Selected Writings, edited by Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings (Harvard UP, 2003), Selected 4: 402.

0 Comments

This is the fourth post in the series Historians Confront the Climate Emergency, hosted by ActiveHistory.ca, NiCHE (Network in Canadian History & Environment), Historical Climatology, and Climate History Network. Ingrid Waldron is the HOPE Chair in Peace and Health in the Global Peace and Social Justice Program in the Faculty of Humanities at McMaster University and the author of There’s Something In The Water: Environmental Racism in Indigenous & Black Communities (Fernwood, 2018). Dr. Waldron spoke with series co-editor Edward Dunsworth over Zoom on 30 June 2021. Transcript edited for clarity and length. Edward Dunsworth: Thank you, Dr. Waldron, for speaking with ActiveHistory.ca today. Your 2018 book, There's Something in The Water, about environmental racism against Black and Indigenous communities in Nova Scotia, has done exceptionally well. Currently in its third reprint, it also was the inspiration for the documentary film of the same name, co-directed and -produced by movie star Elliot Page, that premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2019 and is now streaming on Netflix. Could you tell us a bit about how the book came about?

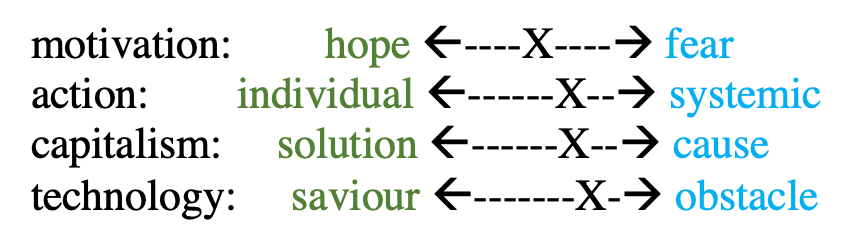

Ingrid Waldon: I had planned on writing a book, but perhaps not so soon. Since starting the Environmental Noxiousness, Racial Inequities & Community Health Project (ENRICH) project in 2012, I’ve been keeping detailed notes. [Editor’s note: ENRICH is “a collaborative community-based research and engagement project on environmental racism in Mi’kmaq and African Nova Scotian communities.”] So I knew that I would use that at some point, but I was planning on a different type of book that would look at the challenges of doing community based research, in general. I was approached by the publisher of Fernwood about writing a book on environmental racism in Nova Scotia. And I thought about it and said yes. The book talks about the ENRICH project, the challenges of community-based research, and the health impacts of environmental racism, all within the context of settler colonialism, heteropatriarchy, and neoliberalism. An important goal of mine with the book was to give voice to the Black and Indigenous communities I engaged. I wanted their voices to be at the forefront. Many of the chapters include direct quotes from them that articulate their experiences and their thoughts on the issues. ED: Tell me a bit about the response to the book and how it eventually led to the documentary film. IW: Well, finally having the book out was really exciting. I did the typical book launches in Nova Scotia and Montreal. The Montreal book launch in 2019 was huge – like 400 people – and they ran out of books. The book has been selling well, despite the fact that Fernwood is a small publishing company. One morning in late October of 2018, I noticed that I had a new follower by the name of Elliot Page. At the time, I did not realize that it was the actor. So I didn't think anything about it. And then three weeks later, I noticed that the page was extremely busy and that Elliot Page had been promoting my book to his followers. I thought, is this the actor from Juno? From Inception? I said, "No, this couldn’t be.” I've never had any celebrity follow me or anything like that. So this was a bit of a shock. But of course it was the Elliot Page. So I reached out and sent him a direct message to thank him for promoting the book, and we began to exchange messages. Eventually we spoke over the phone and began bandying about ideas about how Elliot could support this work. After meeting with Elliot and the three Mi'kmaq women in the film, the grassroots grandmothers, we decided to create a series of short videos that we could post on social media to raise awareness about environmental racism. So in April 2019, Elliot came up and he travelled to the communities and filmed interviews over six days. When Elliot and Ian Daniel, the co-director, showed me a rough, partially completed version of the film, I said, this is emotional. There are people crying. I don't think we're going to do justice to these stories by posting ten-minute clips online. I said to Ian Daniel and Elliot Page that I really thought we needed to do this justice. This is an important topic. And they all agreed. I started talking about the Toronto International Film Festival - you know, "go big or go home." We almost missed the deadline. But we got it in and the film was of course accepted. In September, we all went down to Toronto for the festival, including most of the women in the film. Elliot was kind enough to bring us all down. And I can't tell you how exciting it was. We spoke with media from around the world. It was just a rush. And I would say that beyond the excitement for me is just the impact that it has had, in terms of people reaching out to me and offering to support the communities in various ways. When I left the premiere of the film at TIFF, I was walking to my hotel and I had literally three people stop me on the street to offer to pay for the well in Shelburne. ED: What were some other impacts of the film? IW: Three main things happened after the film was screened at TIFF. I'm not going to say they were only due to the film – I'm not taking anything away from the [decades of organizing by] Mi'kmaq, Indigenous, and Black community members. But I questioned why these things didn't happen before. It demonstrates the power of the media. First of all, after the TIFF screening, Nova Scotia’s government announced that the pulp mill that had been pumping effluent into Boat Harbour in Pictou Landing First Nation since 1967, would close at the end of January 2020, which did happen. Second, [related to the longtime efforts of Mi'kmaq communities to halt the Alton gas project] in March of 2020, for the first time ever, the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia ruled that consultations with the community regarding the project had been insufficient and ordered the Nova Scotia government to go back and consult the community for 120 days. And third was Elliot Page’s gift of a new community well to the Black community in Shelburne. All these things have transpired since the film, and once again, I'm not taking anything away from the [Mi’kmaq and Black] communities and their grassroots mobilizing, but the power of film, the power of media, the power of celebrity, I think put all of this in place in many ways. Everything that we've all been doing is also significant. Community-based research for me as a professor, community mobilizing, grassroots resistance, marches, petition signings, letter writing campaigns, all of that is important. But what I've learned is that everything has to go hand in hand. And it also has to include legislation. People always say to me, what do you think is most important? Is it the grassroots mobilizing? Is it the policy? I always say it's all of them, it's never one thing. ED: You're not a historian in the strict disciplinary sense of the word. But you have a rich historical perspective in the book: in a broad sense, by bringing in the histories of colonialism and slavery, but also in a more localized sense, engaging with the histories of Afro-Nova Scotian and Mi’kmaq communities and the racism they faced. From your perspective, why is a historical perspective important to understanding environmental racism? IW: The first reason, with respect to environmental racism or any issue, is the tendency for some people, typically white people, to say, "Yeah, but that was in the past. Why can't they just get on with it?" My response to them has always been the past is the present and the present is the past. Using an example from my book, it’s important for people to understand why, for example, Black communities live where they live in Nova Scotia. Nova Scotian Black communities are very different from other Black communities in Canada. They're the oldest Black community in Canada; they've been here for about 400 years. They are descendants of Jamaican Maroons, Black Loyalists from the United States, and others. When they arrived in Nova Scotia, they were given poor quality land, which made it difficult for them to engage in agriculture. And that's the land where landfills and dumps and other environmentally dangerous projects tend to be located. So we have to understand the history of African Nova Scotians in order to understand why they live where they live and why environmentally dangerous projects have tended to be placed in their communities. ED: Turning to the question of the climate emergency, what lessons do the history and contemporary practice of environmental racism in Nova Scotia and Canada hold for how we as a society approach the climate crisis? IW: The disproportionate impacts of the climate crisis on Indigenous, Black and other racialized communities is connected to environmental racism, which people are largely not discussing. When you look at environmental racism, Indigenous, Black, other racialized communities are impacted because of the structural inequities that they already face. They are racialized, they're low income, they live in isolated communities, they suffer from income insecurity and poverty and food insecurity, housing insecurity, public infrastructure inequities. So those social determinants of health actually create exposure, make them more vulnerable, make them less likely to be able to fight back because of their lower socio-economic and socio-political status. Those same social determinants also expose them to the climate crisis. Think back to Hurricane Katrina. You have low-income African American communities who have to stay in hostels for months because they were living in areas with low-quality public infrastructure, roads, housing, and so on. Once I started to look at the framework of climate justice, I realized that environmental racism and climate change should not be discussed independent of the other. But race, whether or not people want to talk about it, is central. Not just race, but also gender, socioeconomic status, poverty, social class – all the social determinants of health are central to discussions on climate change and environmental racism. I respect the environmental scientists who talk about greenhouse gas emissions and so on. We need to hear about that. But what is problematic to me is that we're not hearing the other side which I just talked about. We need to have a conversation in Canada about the fact that central to both environmental racism and climate change are the inequities, the longstanding, historically embedded inequities that racialized communities experience. ED: How are Black and Mi'kmaq communities and organizations in Nova Scotia building the climate crisis into their analysis and political work? IW: Indigenous communities, from my perspective, have always had a holistic understanding of the environment. Indigenous communities have an Indigenous epistemology or ecological knowledge that doesn't see a separation between human beings, animals, plants, water, air. So, an Indigenous epistemology understands that if you desecrate the land by placing environmentally hazardous projects in their communities, then you negatively impact the emotional, mental, spiritual and physical health and well-being of individuals. Everything is viewed as interconnected in Indigenous epistemology. Traditional African philosophy also has a holistic understanding of the world. Although it has been challenging to engage Black communities in environmental issues, that is starting to change as I am seeing more Black youth joining and starting initiatives focussed on environmental racism and climate justice. Climate change is going to impact all of us. So I'd like to see more Black communities, not just in Nova Scotia, but across the board, be more engaged in this issue. And I think part of the reason why they haven't been is that the movement is very white. [With both environmental racism and climate change], the scholars are typically white, the people who write books on these issues are white, and for Black people looking at this, they're like, “I don't think I have a place in this.” So that's why I've done the work that I've done. I don’t think mainstream environmentalists’ focus on greenhouse gas emissions is engaging to a lot of people. People don’t understand their place in that issue. It pushes people away to some extent; even those who are highly educated. [Dr. Waldron and I closed our conversation by talking about climate change adaptation in Black communities in Nova Scotia. Dr. Waldron explained that despite all the intersecting vulnerabilities faced by Afro-Nova Scotians, other characteristics of those communities position them well to adapt to changing environmental conditions.] IW: The Black communities I have met over the years in Nova Scotia love their community. There is a great sense of community solidarity, which I admire. That sense of solidarity often comes from a place of marginality. Out of marginality comes great things. In my work, my goal is always to build on community spirit and resilience to develop capacity in communities that have long been on the margins. Thank you to Megan Coulter for her work transcribing this interview. This is the third post in the series Historians Confront the Climate Emergency, hosted by ActiveHistory.ca, NiCHE (Network in Canadian History & Environment), Historical Climatology, and Climate History Network. Dr. Daniel Macfarlane, Western Michigan University We’re in a climate emergency. This isn’t just rhetorical hyperbole, but a statement backed by more than 13,000 scientists. Even the venerable publication Scientific American agreed to adopt the term earlier this year. Canada is particularly culpable for this crisis because of its petro-state status and hyper-consumerism. My research deals with the transborder history and politics of Canada-U.S. water and energy issues, lately involving climate change. But it is in my teaching role that I spend the most time addressing the climate emergency since I’m in an environmental and sustainability studies department (which has a climate change minor). This includes an introductory course that features a major climate change component, as well as senior courses such as the seminar I’m teaching this fall that concentrates on my campus’s carbon emissions. True, I have the advantage of teaching in an environment-focused setting that looks as much at the present and the future as the past. But all historians, regardless of experience in environmental history or history of science, can bring the climate emergency into their classroom. What I would like to do in this post is to suggest some areas, based on my teaching experiences and reading of recent literature, where climate change could be injected into Canadian history survey courses. During the pandemic, I’ve read a wide range of new popular books about the climate crisis – from the technocratic solutions of Bill Gates to the Green New Deal advocacy of Kate Aronoff. Within those public-facing books, I noticed four key debates – or spectrums since they don’t have to be either-or questions – about tackling climate. These are illustrated below, with the ‘X’ marking where I land within each: I could write a whole post about why I fall where I do. But that isn’t the point here. Instead, I’m going to offer strategies for infusing lectures, discussions, and assignments with aspects of those four debates. Probably the most obvious way to do that is enhance the emphasis on natural resources. Climate change, as well as our other big ecological problems, are tightly linked to how we use and consume resources. The most relevant type of resource when it comes to greenhouse gases is energy. Canadians have long been amongst the most profligate people in the history of the globe in terms of energy consumption (only some of which can be explained by Canada’s widely dispersed population and cold climate). Canada has also been a global production leader in several different energy forms, with hydroelectricity and oil likely the most well-known (though we could count uranium as well because of its role in nuclear power). To incorporate energy history, university instructors could go several routes, such as peppering it into lectures throughout the term, or create an entire section or module. It just so happens that the major energy eras and transitions line up pretty well with major periods of Canadian history extending deep back into the premodern period: animal/human muscle, wood, coal, hydro, fossil fuels, etc. Truthfully, energy could be the organizing principle for an entire survey course (and this book would make a great text). The development of energy is intrinsically tied to common classroom themes in Canadian political history: federalism (disputes over provincial rights to harvest hydropower and fossil fuels); regional identity (Ontario Hydro, Hydro-Québec, and BC Hydro; the prairies and oil; coal on the east coast; etc.); Canada-U.S. relations (electricity, fossil fuel, and uranium exports). Many major topics that normally come up anyway, from the railways to free trade, are inherently about energy and environment, providing segues to wrestle with climate change and Canada’s contribution and response to it.

Hydroelectric dams, fossil fuels, and pipelines have long wreaked havoc on First Nations communities. The history of energy developments therefore also dovetails with Canada’s history of settler and extractive colonialism. And discussions about reconciliation can relate to contemporary calls for a just transition away from fossil fuels. Tying in with the systemic vs. individual debate, other aspects of the history of social movements and human rights in Canada could be an entrée for grappling with climate change. Sticking with the systemic angle, another existing theme in the Canadian curriculum where climate change could clearly piggyback is the role of the state. The history of capitalism is yet another prevalent theme that can be merged with exploring climate change. The tension between government regulation and intervention versus the free market is already apparent in Canadian history and lends itself to talking about capitalism as the solution or the cause. For those addressing the history of technology, Canada has been at the forefront of a number of technological changes dealing with the extraction and burning of energy, from the world’s biggest hydropower stations a century ago to the tar sands today. Technology is why we have cheap energy. Cheap energy is a sine qua non of “modern” Canadian lifestyles, the reason why consumer products are (relative to their true cost) inexpensive and available. And cheap energy is a major reason, maybe the main reason, we have climate change. The extraction and production of energy – e.g., coal miners and oil roughnecks – connects with important themes in labour and class history, while the ways energy is consumed – such as household work or petro-masculinity – can be combined with themes in social and gender history. And how has cheap energy and the attendant assumptions of abundance practically and conceptually shaped modern Canadian society and Canadian identity? Students are frequently interested in studying the differences between Canada and the United States. Canada’s social safety net and collectivism are often held up as distinctive from American individualism and privatization. But that may be the narcissism of small differences relative to the historic exploitation of natural resources, per capita levels of consumption, and greenhouse gas emissions; on those scores, to the rest of the globe the U.S. and Canada look pretty identical. When it comes time to teach about Canadian international history, for all the claims about Canada’s middle power or peacekeeper proclivities, it is in the realm of fossil fuels and climate change that Canada might actually be a superpower (but the bad kind). Another pedagogical approach is to look at past adaptations to a changing climate. That is, the climate has shifted in the past, and peoples living in the territory now called Canada had to figure out ways to cope. If you’re teaching the pre-Confederation survey, the Little Ice Age (roughly the 16th to the 18th centuries) caused changes to food acquisition and agriculture strategies, which in turn had social, political, and military knock-on effects. Resilience emerges as a theme to interlink cultural responses to climate change in the past and present. For those doing post-Confederation history, many of the climactic shifts we currently recognize were already occurring by the Second World War. The start of the Cold War is one of the candidates for dating the beginning of the Anthropocene, which could serve as an organizing topic or concept (this series will have more on the Anthropocene in future posts). What about some specific class exercises and assignments? Try integrating historical sources as indirect proxies for comparing climate from past to present. You might have heard of using ice cores, sediments, or tree rings to infer historic climatic conditions. But the types of records historians are likely more familiar with, such as paintings, diaries, ship or whaling log books, and fur trade fort journals, can also be revealing and double as a unique way to introduce undergrads to the use of primary sources. (A contributor to this series, Dagomar Degroot, has written extensively about the use of various textual records for climate history). Artistic representations can show glacial retreat or pollution levels, for example. Or, given the prominence of the fur trade in Canada’s history, using fort journals to compare past temperatures and change of seasons with the present could be an instructive way to expose students to both climate history and primary sources. There are places online where some of those types of information are already organized for easy integration into your curriculum. For the pre-Confederation period, check out Canada’s Year Without a Summer. The titular year in question is 1816; the Tambora volcano erupted the previous year in Indonesia, leading to subsequent cold weather in early eastern Canada. This website was created by Alan MacEachern and Michael O’Hagan with course instructors in mind: it offers more than 120 sources, as well as guidance for how teachers could incorporate these into class. For the post-Confederation period, try Environment Canada’s National Climate Data and Information Archive which has (digital) reams of historical climate data. A professor could create an exercise or assignment, for example, in which students pick a location – such as their hometown or their university – and compare past and present weather/climate conditions. This is not an exhaustive list of ideas, but some easy ways to get started. Given the reality and urgency of the climate crisis, and its relevance to the lives and concerns of students, it is something all introductory history courses need to address. Daniel Macfarlane is an Associate Professor in the Institute of the Environment and Sustainability at Western Michigan University, co-editor of The Otter-La loutre, and a member of the executive board of NiCHE, Network in Canadian History & Environment. This is the second post in the series Historians Confront the Climate Emergency, hosted by ActiveHistory.ca, NiCHE (Network in Canadian History & Environment), Historical Climatology, and Climate History Network. Dr. Dagomar Degroot, Georgetown University Historians have always concerned themselves as much with the present as the past. Some do so explicitly, their work guided by a conscious desire to provide context for a matter of present concern. Others do so implicitly. They may study the past because it makes them curious, but that curiosity is inevitably shaped by their day-to-day lives. One way or another, history as a discipline is the outcome of the history historians must live through. Today no challenge seems more daunting than the climate crisis. Earth’s average temperature has warmed by over one degree Celsius since the nineteenth century, and it is likely – though not inevitable – that much more warming is on its way. Global temperature changes of this magnitude, with this speed, profoundly alter both the local likelihood and severity of extreme weather. Human-caused heating will reverberate through the Earth for millennia – by slowly melting ice sheets and raising sea levels, for example. Our lives and livelihoods will be – in many cases, are already – shaped by this crisis. No surprise, then, that ever more historians now think urgently and seriously about the implications of climate change for their scholarship. Forecasts of the warmer future are still dominated by economics and climate science, but few now deny that scholars of the past – including historians – can offer unique perspectives on how we entered this crisis, where it might be taking us, and how we can avoid its greatest dangers. As this series reveals, historians grapple with climate change in increasingly diverse ways, and here it is again useful to draw a distinction between implicit and explicit approaches. In a sense, just about every kind of history has relevance to the present crisis, because climate affects every aspect of the human experience. Climate change alters the environments that sustain and shape our lives, shifting the basic conditions that channel our actions and thoughts. The climate crisis is therefore as much about the transformation of the planet as it is about the reshaping of human relationships. Any history that deals with those relationships – all history, by definition – implicitly tells us something about climate change and its social consequences. If you are a historian, your work is about global warming. The editors of this series, however, asked me to describe how scholars of the past explicitly engage with the climate crisis. Arguably, the most influential and numerous publications have originated in both the history of science and the related fields of climate history and historical climatology. A quick and necessarily incomplete overview of just these two kinds of scholarship reveals the value and diversity of historical approaches to climate change. Historians of science initially concentrated on how global warming was discovered and understood by scientists with increasing certainty. While it is simplistic to conclude that scientists “knew” about global warming for many decades, or even over a century – as is often stated in popular media and occasionally in scholarship – historians of science nevertheless revealed the deep roots of today’s scientific understanding of global warming. Led by Naomi Oreskes, they also found that serious debate among climate scientists over the existence of human-caused global warming ended in the 1990s, or perhaps even earlier. Although a majority of the public doesn’t know it, just about every climate scientists understands that humans are today responsible for the rapid heating of the planet. Confirming the scientific consensus on global warming led some historians of science to argue that fossil fuel companies and far-right scientists cynically promoted climate denial in order to serve their regressive political or economic interests. This was – and remains – perhaps the most influential and politically potent argument proposed by historians about the climate crisis. Climate scientists, in this narrative, bravely announced their inconvenient truths but could not overcome the falsehoods propagated by their more media-savvy antagonists. Nevertheless, other historians soon pointed out that climate science has long involved more than the apolitical discovery and communication of truth. Historians of science revealed for example how models and simulations came to dominate climate science – rather than other ways of knowing – and argued that climate scientists themselves failed to choose communications strategies that could mobilize grassroots, local action. Historians have long traced the emergence of ideas about climate from antiquity through the present. Recently, historians of science have revealed that the climate ideas most view as characteristically modern in fact have deep roots. They have shown, for example, that legends of ancient climate changes caused by human sin or shortsightedness helped influence the development of early modern science, and – with new practices in forestry and agriculture – contributed to the emergence of what we might now call sustainability thinking. Climate historians and historical climatologists take an entirely different approach to the climate crisis. Historians active in historical climatology search for human records – usually documents – that either describe past weather or activities that must have been strongly influenced by weather. By finding enough of these records – by scouring what they call the “archives of society” – historical climatologists uncover how climate changed over decades or even centuries. Working with those who uncover evidence for past weather in the “archives of nature” – tree rings, ice cores, or lakebed sediments, for example – they can develop remarkably precise “reconstructions” that reveal the existence of substantial climatic fluctuations even before the onset of today’s extreme warming. The antecedents of this work date back to the nineteenth century, but it was really only in the 1970s that Christian Pfister and other pioneers proposed ranking qualitative accounts of weather on simple ordinal scales. These scales allowed for the closer integration of the archives of society with the archives of nature, especially in Europe, but historical climatologists studying different parts of the world continued to use distinct methods for quantifying historical evidence. Only now are they working towards developing a common approach. In any case, reconstructions permit histories of human responses to past climate changes. While these climate changes have been relatively modest in global scale – the Little Ice Age, the most studied period of preindustrial climate change, only cooled the Earth by several tenths of a degree Celsius between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries – some were nevertheless sufficient to dramatically alter local environments. Archaeologists, economists, geneticists, geographers, linguists, literary scholars, and paleoscientists have all used distinct methods and sources to uncover how these alterations shaped the history of human populations. Yet few disciplines have contributed more to this scholarship – recently coined the “History of Climate and Society” – than history. Historians have in recent years increasingly avoided making simple connections between climate changes, harvest failures, and demographic disasters: a chain of events that scholars of past climate have long emphasized. New climate histories instead uncover wellsprings of both vulnerability and resilience within communities, and they increasingly consider the full range of possible relationships between climate change and human history across the entire world and into the twentieth century. Together, historians of science and climate historians have done much more than add a little climate to historians’ understanding of the past. Histories of climate science help uncover why governments and corporations have not responded quickly or adequately to the climate crisis. They also reveal how the crisis might be communicated more effectively, or how more diverse ways of knowing could be incorporated within climate science. They show us why we should nevertheless believe the forecasts of climate science – and how we can best act on that belief. Historical climatology helps reveal the baselines against which human emissions are changing Earth’s climate today, and helps uncover the likely response of local environments to global warming. Climate historians can suggest what strategies may succeed or fail when climates change, and add complexity to forecasts of the future that too often assume simple social responses to shifting environmental conditions. Many tell stories about the influence of climate on human affairs that capture public attention more vividly than frightening statistics ever could. Yet both climate history and historical climatology also demonstrate the fundamental discontinuity between climates present and past. The speed, magnitude, and cause of present-day warming simply has no parallel in the history of human civilization. History is a guide to climate action, but it also warns us that to a large extent we are in uncharted waters. Ten years ago, when I started this website, my message was something like: believe me, history helps us understand global warming! I could not have imagined that, in just ten years, climate change would be widely recognized as a serious subject for historical study – or that historians such as Ruth Morgan would earn a seat in a working group of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In some ways, the sea change in the historical discipline has mirrored a broader transformation in social attitudes towards climate change: a transformation driven in part by the courage of young activists, but also by the growing severity of the climate crisis. Climate scholarship in history is now more numerous and more diverse – in its topics and authorship – than it ever has been, a shift that also echoes developments in climate activism.

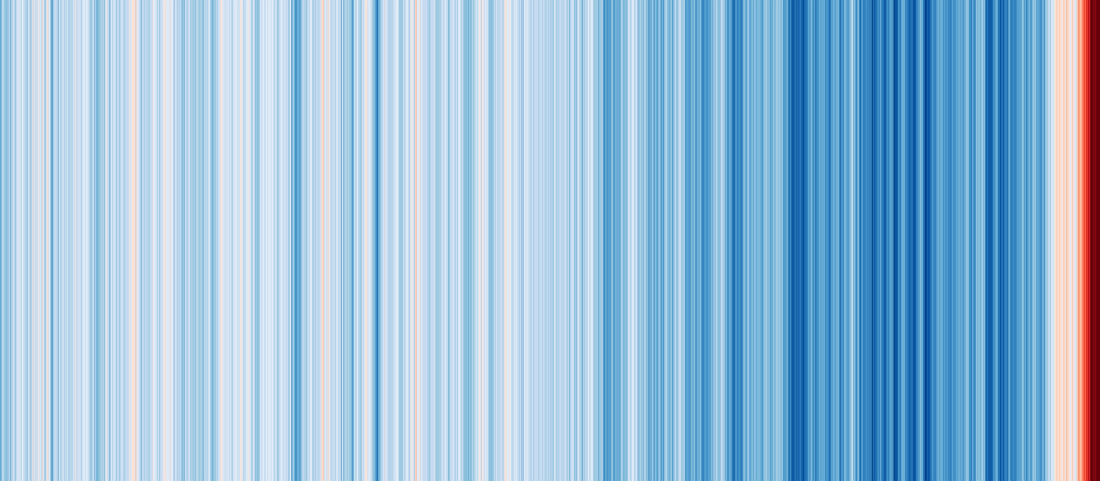

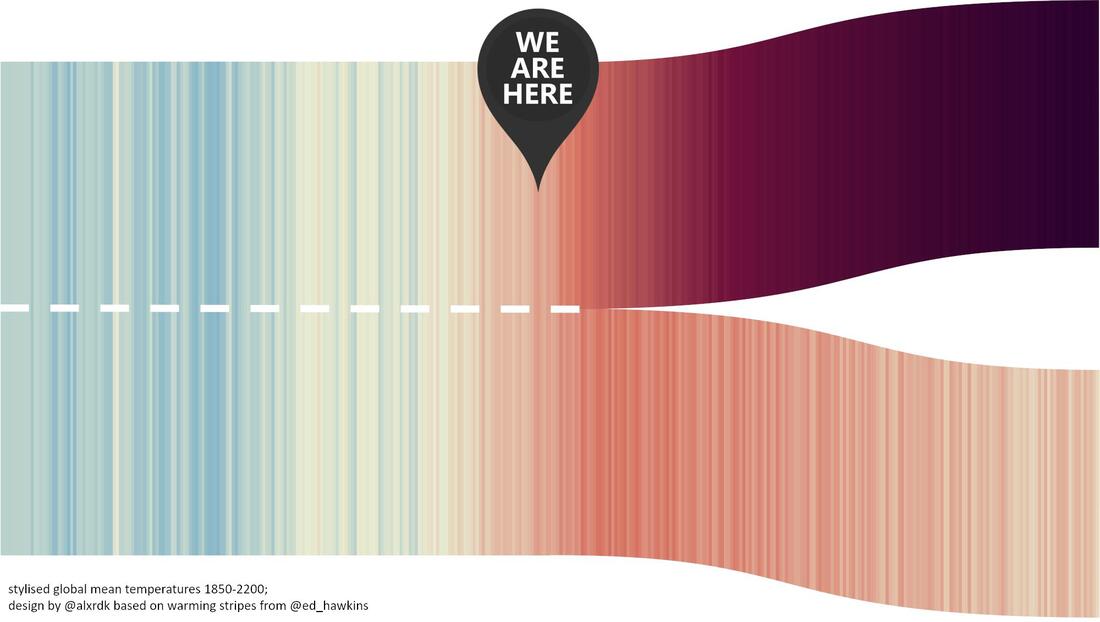

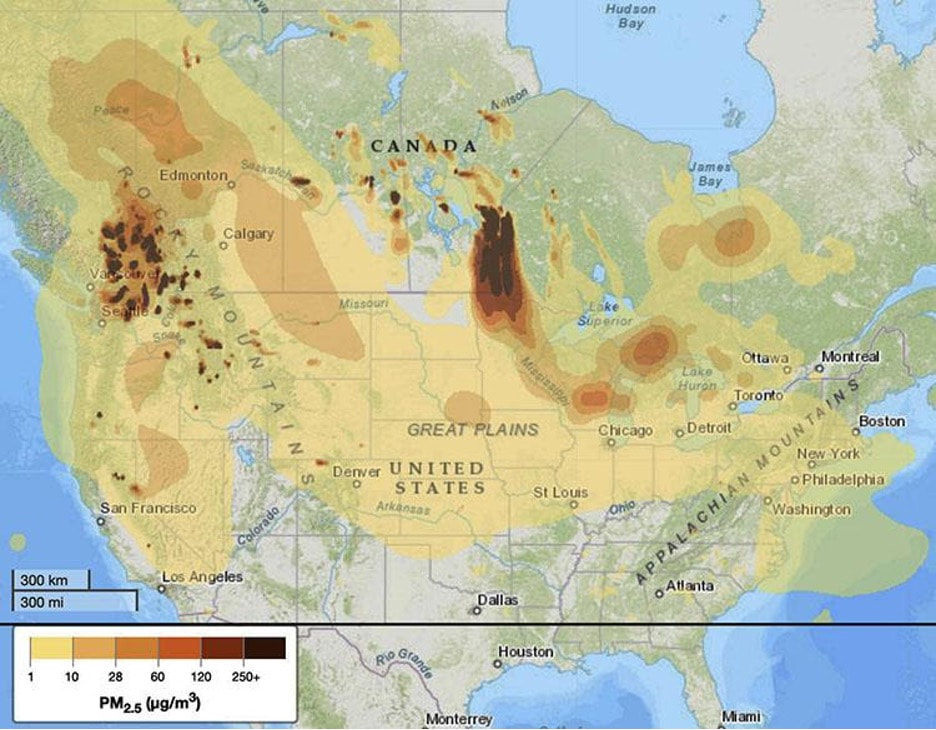

I expect these trends to continue. When future historians write about our time, you can be sure that climate change will play a central role in the story. As we live through that history, our scholarship will be climate scholarship – whether we see it that way or not. This is the introductory post to the series, “Historians Confront the Climate Emergency,” hosted by ActiveHistory.ca, NiCHE (Network in Canadian History & Environment), Historical Climatology and Climate History Network. Dr. Edward Dunsworth and Dr. Daniel Macfarlane What a summer. In late June, a “heat dome” stalked the Pacific regions of Canada and the United States, pushing thermometers close to the 50-degree mark and causing the sudden death of 570 people in British Columbia alone. By July, hundreds of forest fires raged throughout the west coast and in the prairie regions of northern North America, their smoke billowing out across much of the rest of the continent. Parts of Turkey, Macedonia, Italy, Greece, and Tunisia were also devastated by forest fires (with Argentina hit during the southern hemisphere’s summer months earlier in the year). Deadly floods in China, Niger, Somalia, India, Germany, Brazil, and Guyana, killing hundreds and causing damage in the tens of billions of dollars. Drought in Iraq, Syria, Ethiopia, Iran, and Madagascar, driving millions towards food insecurity and starvation (400,000 people in Madagascar alone are at risk of starvation). Hurricanes, tropical storms, and cyclones battering the Caribbean and United States; Laos, the Philippines, and Indonesia; India and Bangladesh; Mozambique and Tanzania.[i] In case the burning mountains, sinking villages, swimming subway trains, and starving masses weren’t evidence enough, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released yet another alarming report stressing the imperative urgency of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The 2015 Paris Agreement had laid out a goal of limiting global warming to well below 2, preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels. But this newest IPCC report made it clear that those targets were by now almost unattainable, and devoted significant attention to the looming risk of “tipping points” – such as the melting of Arctic permafrost – that are likely to trigger cascading events and result in fundamental, and potentially irreversible, transformations to Earth systems. The media rolled out phrases like ‘code red’ or ‘emergency’ or ‘wake-up call’. “The alarm bells are deafening,” said the UN Secretary-General. And – oh yeah – a pandemic whose genesis was almost certainly linked to climate change continued to ravage the globe, claiming its four millionth victim and showing little signs of abating – certainly not among the vast majority of the planet’s people who have not yet had the privilege of vaccination. Meanwhile, amid this ever-growing list of ominous events, we – the authors of this post, but also many of you readers – carried out our work as historians: researching and writing books and articles, delivering conference papers, preparing syllabi, grading papers, processing evermore perplexing emails from university administrators, and all the rest of it. It all seemed a bit disjointed, a bit discordant, a bit surreal. Here was Ed, gazing up at a Montreal sky darkened by smoke from forest fires along the Manitoba-Ontario border, nearly 2,000 kilometres away, working away at revisions on a book about tobacco farm labour in 20th century Ontario. There was Dan, preparing a syllabus on carbon emissions and interviewing people about historical climate change impacts on Lake Ontario, taking a break to read the dire warnings of the IPCC about the very survival of our planet. We are in a climate emergency. But still the humdrum – and at times not so humdrum – beat of everyday life carries on. The dissonance of it all can prompt some big questions, even existential ones, for historians. What does it mean to be a historian on a planet on fire? What does it mean to study the human past when the human future is in dire peril? This series does not claim to answer these questions. Indeed, the answers to them will be worked out by all of us, in collective dialogue and debate, over the decades to come. Instead, we have more modest aims, but ones that we nonetheless hope will encourage scholars of the past – in whatever discipline they find themselves – to think in new ways about how the work of historians might speak to the totalizing crisis at whose precipice humanity now stands. For this ten-part series, we asked a wide-ranging and interdisciplinary roster of contributors to respond to the following animating questions: how should we historians and academics respond to the climate crisis? And how are we already doing so, in our research and our teaching? From its conception, a key aim of this series has been to bring scholars from fields other than environmental or climate history into the conversation about the climate emergency and how it relates to the work of historians. (Indeed, the very editorship of the series reflects this intention, with environmental historian Dan joining labour and migration historian Ed as co-editors). It struck us that since the climate emergency is not simply an environmental development, but also a social and political one, one that intersects with innumerable other processes – from colonialism to capitalism to migration to gender to racism to global inequality to diplomacy and so on – then it follows that historians from a diverse range of subfields should have lots to say about the crisis, leveraging their expertise towards a richer understanding of its origins, thereby enabling sounder approaches towards its resolution. In practice, however, we found this to be a more difficult task than anticipated. In putting together the series a trend quickly emerged in which historians in the usual-suspect subfields readily said “yes” to participating, while bringing in voices from other fields proved more challenging (though well worth the effort given the stellar contributors we ultimately lined up). Perhaps this was a fluke and no grand lessons should be gleaned from it. But perhaps it speaks to some of the barriers that exist to engaging with the climate emergency as historians. Incorporating a technical and science-heavy subject – and one that may seem more contemporary and future-oriented than historical – into writing or teaching can be intimidating for those who aren’t environmental or climate historians. With this in mind, we in part envision this series as aimed at those folks who want to engage with the climate crisis in their work as historians but may be unsure about where to start. We hope this series can provide some avenues for thinking about, and incorporating, the climate crisis into their work as teachers, researchers, and writers. The series will run over the next five weeks, with posts appearing on Tuesdays and Thursdays on both ActiveHistory.ca and NiCHE (and cross-posted on HistoricalClimatology.com and ClimateHistory.net). The contributions can be loosely grouped into two main categories: “Critical perspectives on the climate emergency” and “Climate in the classroom.” The series features contributors from a range of scholarly disciplines with a diverse array of research interests, who run the gamut from emerging scholars to renowned experts in their fields. In titling the series, “Historians Confront the Climate Emergency,” we are claiming an expansive definition of historian that has less to do with disciplinary boundaries and instead simply refers to anyone who studies the past; and more to the point, for our purposes as “active historians,” to anyone who studies the past with an eye to better understanding, and thus better informing, the present. Over the next five weeks, we are thrilled to share contributions from:

Stay tuned. Daniel Macfarlane is an Associate Professor in the Institute of the Environment and Sustainability at Western Michigan University, co-editor of The Otter-La loutre, and a member of the executive board of NiCHE, Network in Canadian History & Environment. Edward Dunsworth is an Assistant Professor in the Department of History and Classical Studies at McGill University and a member of the editorial committee at ActiveHistory.ca. [i] Examples drawn from a number of news reports and from the impressive International Disaster Database, from the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters at the Université catholique de Louvain, Belgium.

|

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed