|

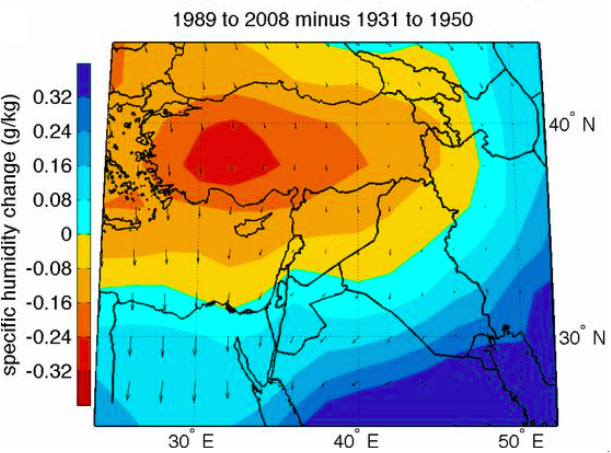

Across much of the world, climate change is making, or will soon make, environments less capable of supporting human life. Anyone who has seen the movie Mad Max will be familiar with the assumption that a hotter, and, in some places, drier climate will drive people to greater competition. When that competition is for the essentials of life, and there is not enough to go round, people resort to violence. In short: global warming could make war even more common than it is today. In Syria and Iraq, we may be getting a glimpse of what such a future might look like. Earlier this year, a team led by climatologist Colin Kelley of the University of California published an article in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that connected climate change to the ongoing civil war in Syria. Between 2006 and 2009, the people of Syria suffered during the most severe drought that country has experienced since the beginning of its instrumental record. As water became scarce, crops failed, and cattle died on a huge scale. As many as 1.5 million Syrians, out of a population of just over 20 million, moved from the countryside to the outskirts of already overflowing cities (Kelley et al., 3242). Out of work, desperate, and living in poorly planned, crime-ridden neighbourhoods, many refugees were quick to revolt against a brutal regime that had long avoided such challenges. There is a mountainous literature that supports the idea that rapid and unexpected population growth can destabilize a society (or indeed, any population of living beings). Certainly, the population of Syrian cities surged. A Syrian farmer quoted by Kelley and his coauthors confirmed that “of course” drought, migration, and unemployment had pushed many toward rebellion. According to the farmer, “when the drought happened, we could handle it for two years, and then we said, ‘It’s enough’” (Kelley et al., 3245). In Syria, connections between drought, dearth, and rebellion therefore seem clear. But did global warming play a role by starting the Syrian drought? Kelley and his coauthors think so. In order to find out, they needed to separate the influence of anthropogenic climate change from the natural variability of the Syrian climate. In the past, that variability has been sufficient to stimulate droughts across Syria, most recently in the 1950s, 1980s, and 1990s. However, precipitation in the country has been declining steadily for at least 80 years. According to computer simulations, westerly winds carrying moist airs from the Mediterranean have weakened, while warmer temperatures have increased rates of evaporation. In other words: less water arrives in Syria from elsewhere, and the water that does appear is vaporized more quickly than before (Kelley et al., 3245). According to Kelley and his coauthors, the global climate models used by the IPCC approximately match the observational record of Syria’s climate over the last century. They reveal that the warming, drying trend in Syria is almost certainly caused by carbon released into the air by human beings. Computer simulations used by Kelley and his coauthors ultimately show that the 2006-2009 drought was two to three times more likely to occur in today’s climate than the one that preceded it. That still does not “prove” that climate change caused the Syrian drought, but demands for proof usually come from those who do not understand how research works. Scientists and other scholars uncover probable relationships, because we can never be absolutely certain about anything. Kelley and his colleagues have shown that we can be quite sure that catastrophic drought in Syria was related to a warmer, drier climate (Kelley et al., 3245). Nevertheless, the authors acknowledge that climate change did not simplistically “cause” drought and civil war in Syria. They cite the destabilizing corruption of the Assad regime, and the extreme social inequality it fostered. They could have also mentioned that secular, despotic regimes, like the one led by Bashar al-Assad, were threatened by both liberal and fundamentalist resistance movements during the “Arab Spring.” Moreover, Kelley and his coauthors find that, in 2006, Syria was unusually vulnerable to drought and its consequences. Bashar’s father, Hafez al-Assad, unsustainably intensified agricultural production in ways that strained already precarious water resources. In particular, irrigation farming severely depleted groundwater, drying the Khabur River and removing an essential buffer between dryness and agricultural collapse. Drought in the 1990s had also undermined the agricultural sector in Syria, which could not recover fully before 2006. Finally, the 1.5 million refugees who fled the effects of drought joined an existing refugee crisis caused by the American invasion of Iraq (Kelley et al., 3241). Some scholars, like political scientist Thomas Bernauer of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, have even cast doubt on the connection between drought and the Syrian civil war. Indeed, we have a tendency to assume that resource shortages lead to conflict, but research in environmental history has shown that this view can be ahistorical. Take rivers that are split between different communities, or “users.” Actions by upstream users can have severe consequences for downstream users. In periods of scarcity, attempts by upstream users to irrigate arid environments with river water, for example, may convince downstream users that violence is the only way out. Yet there is ample evidence to suggest that initial competition for river resources can lead to cooperation. When lives and livelihoods are all tied to the same precious water supply, competition is likely to be counterproductive in the long run. Severe storms provide further examples. Much was made of so-called “looting” in the wake of hurricane Katrina. In fact, disaster relief in the wake of major hurricanes and cyclones has repeatedly linked communities to networks of national, or even global, cooperation. Nevertheless, outside observers and Syrians themselves have made a convincing case that, in Syria, a severe drought caused profound socioeconomic disruptions, which in turn contributed to rebellion and civil war. Kelley and his coauthors have shown that climate change played a significant role in making that drought more likely. Ultimately, their research raises some important lessons for our understanding of relationships between climate change and conflict. It seems that global climate change can act as a catalyst for violence when it causes disruptions in regional weather that happen suddenly, provoke shortages of food and employment, and occur in an unstable socioeconomic context.

Even then, studies in climate history demonstrate that links between moderate climate change and war are never straightforward. Let us hope that this does not change in a much warmer future. ~Dagomar Degroot Source: Colin P. Kelley, Shahrzad Mohtadi, Mark A. Cane, Richard Seager, and Yochanan Kushnir, "Climate change in the Fertile Crescent and implications of the recent Syrian drought." PNAS 112:11 (2015): 3241-3246 Read an interview with Colin Kelley. |

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed