|

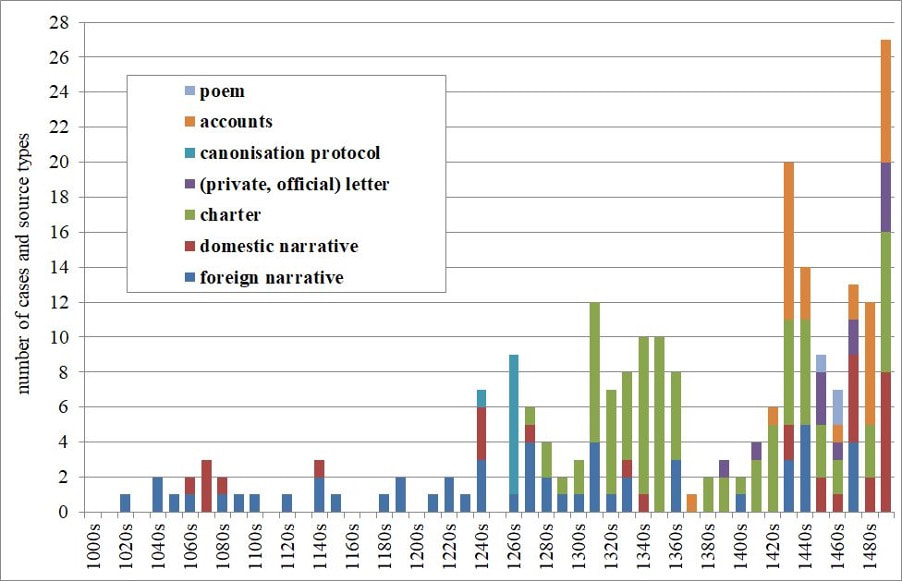

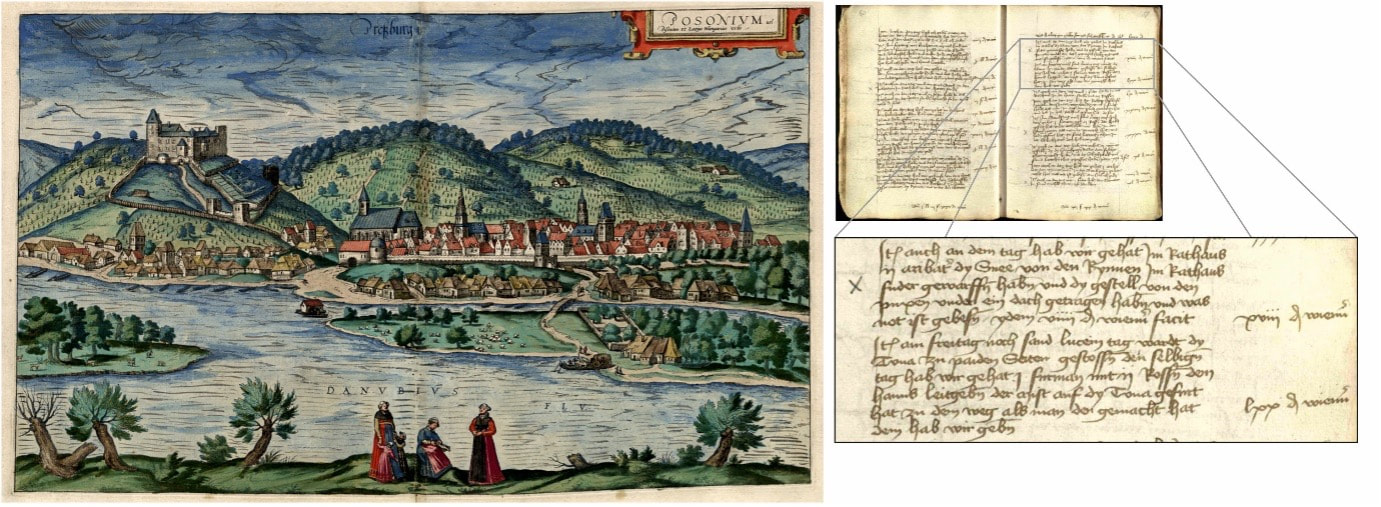

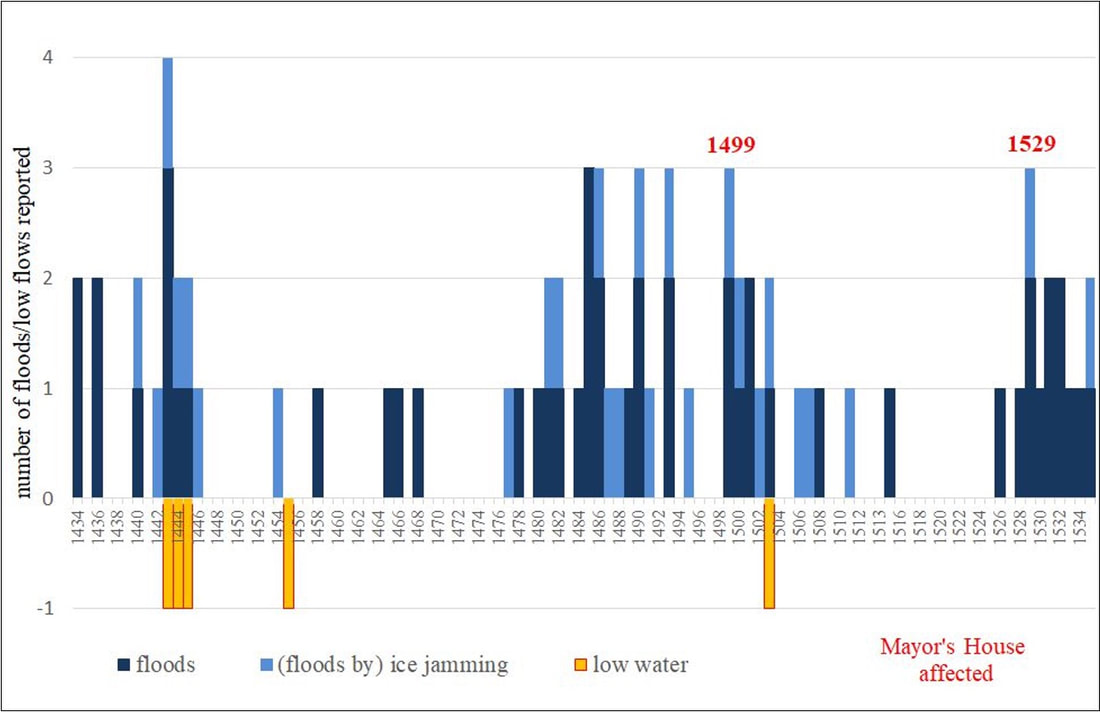

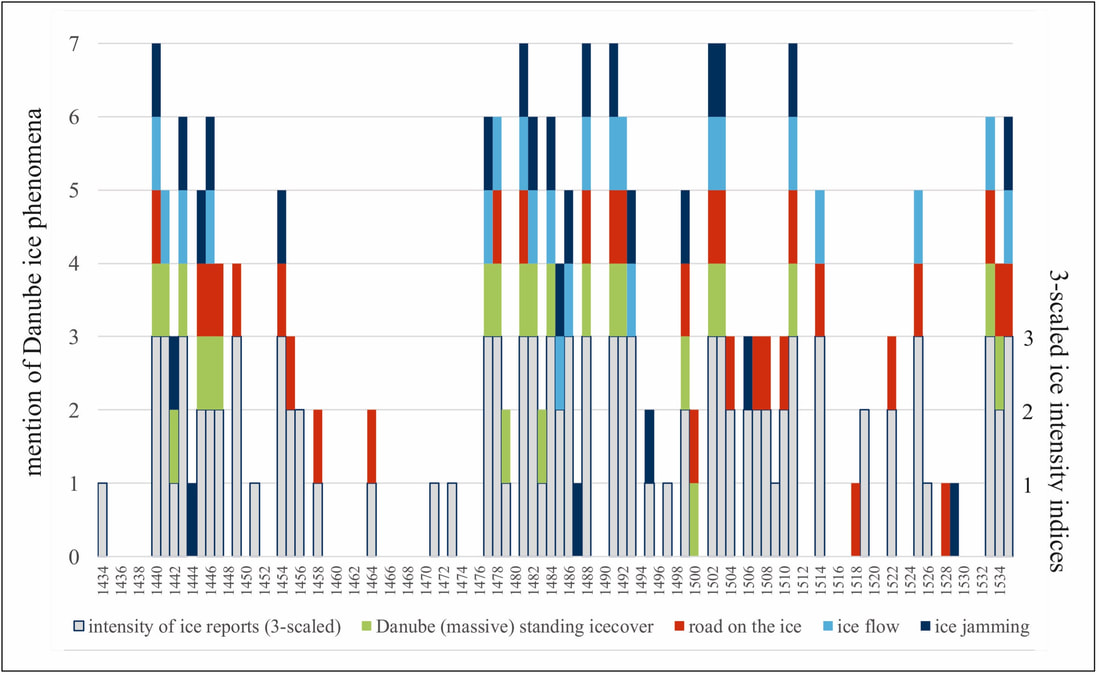

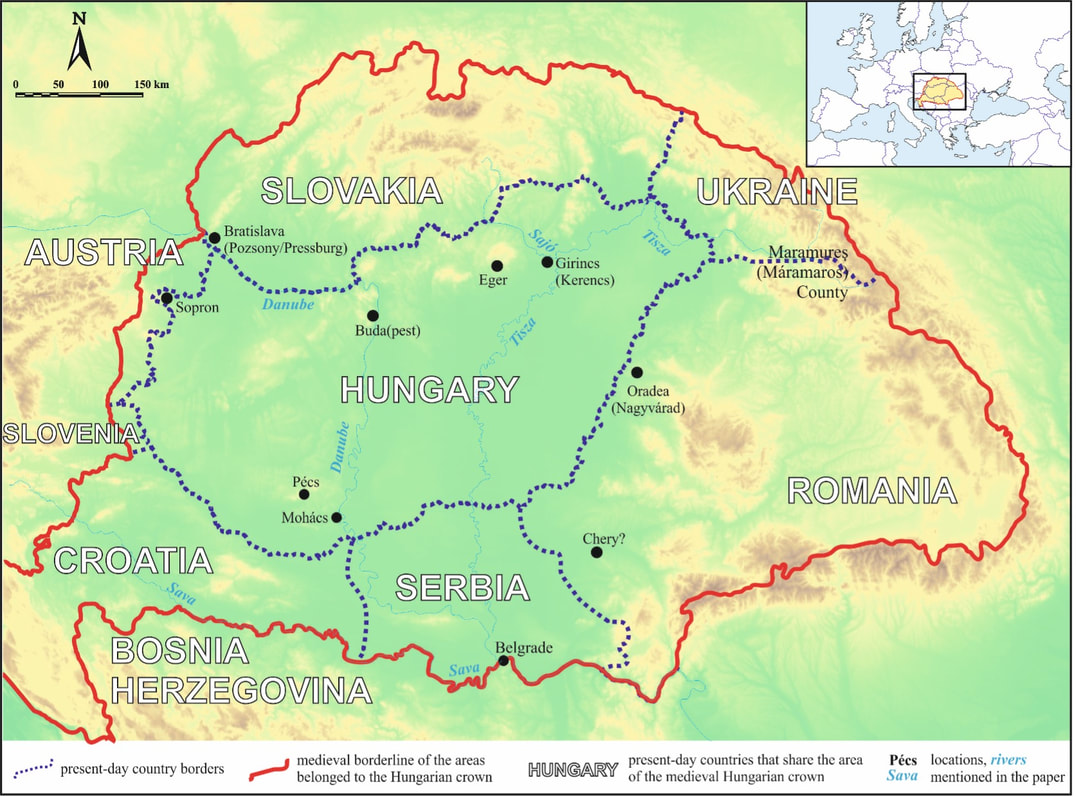

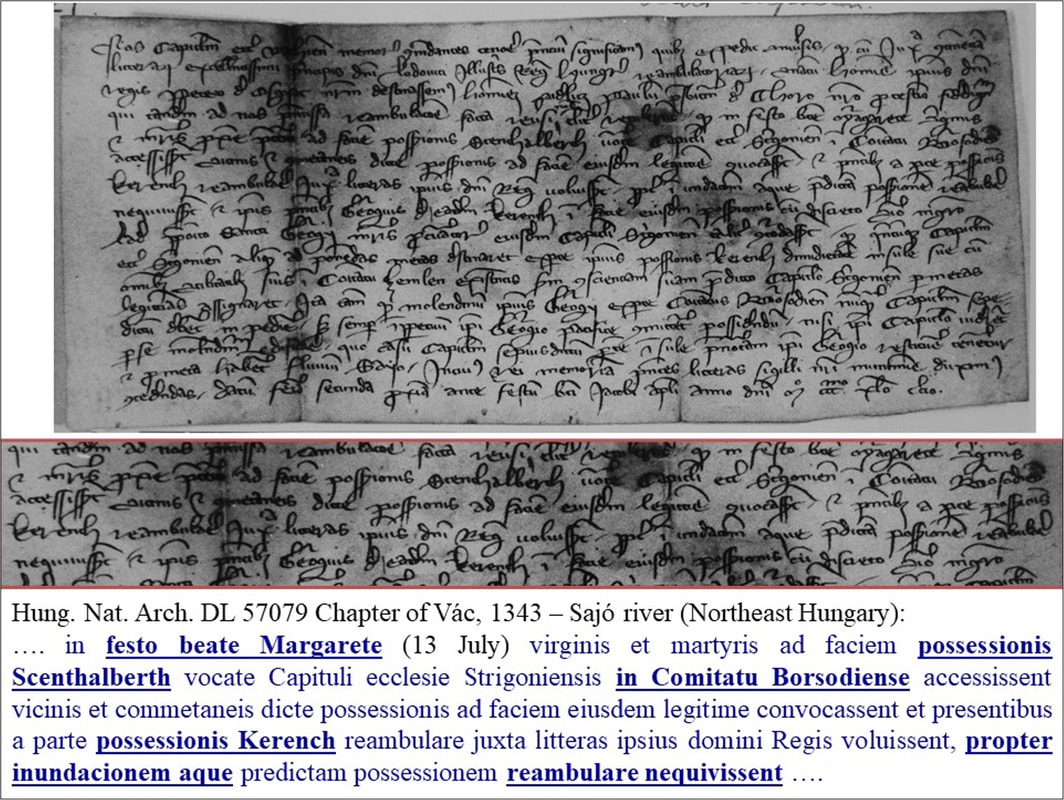

Dr. Andrea Kiss, Technische Universität Wien General background The countries of the Hungarian Crown - with the Hungarian kingdom the most prominent - represented one of the key political and military powers in East-Central Europe in the Middle Ages. The Hungarian kingdom alone (which included present-day Hungary, Slovakia, Eastern Austria, Eastern Slovenia, Western Ukraine, Western and Central Romania, Northern Serbia, and Northern Croatia) occupied an area (325,000 km2) larger than the entire British Isles. When combined with the 42,000 km2 Slavonia (present-day Central, Northern Croatia and North-west Bosnia), it covered the entire Carpathian Basin (Fig. 1). Population density was well under the high-medieval average for Western Europe, but the region was less affected by the Black Death than other areas, so by the mid-14th century, the figure was more comparable. The end of the Middle Ages was marked by the Battle of Mohács (1526), when the Hungarian royal army was crushed by the incomparably larger Ottoman forces. Isolated examples of documents referring to the weather survive from the high medieval (11th-13th century) period; records are more frequent from the mid-to-late 13th century and especially from the early 14th century. What makes the Carpathian Basin truly unique compared with the rest of Europe is the composition of contemporary source types, above all those containing weather-related information. Contemporary sources – vivid real-life weather and flood reports The medieval climate- and environment-related sources from the Carpathian Basin are rather special because, except for the mid-to-late 15th century, the main European sources of historical climate analysis (i.e., chronicles and annals) are mostly lacking. Instead, there are tens of thousands of particularly rich and detailed charters dating from the 13th and especially the early 14th centuries containing lengthy field surveys and descriptions of environmental and weather conditions. Additionally, economic-administrative documents are available sporadically from the 14th and systematic from the 1430s onwards; among these, especially the chamberlain accounts of Bratislava (historical Pozsony/Pressburg; hereafter Pressburg accounts) provide a great deal of weather-related information (Fig. 2).  Fig. 2 Decadal distribution of weather-related source types (floods excluded; for floods, see: Kiss, 2019) in the medieval Carpathian Basin (1000-1500; work in progress) each source with weather report taken as one case. Published data: Kiss 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017, 2020a; Kiss and Nikolić-Jakus, 2015 Charters, letters, and town, estate and tithe accounts occasionally contain short but very realistic and punctual reports on actual weather conditions (e.g., rainy, snowy, foggy, hot, cold), weather extremes (e.g., storm, thunderstorm, hail, and so on), and weather-related extremes (especially floods and some of the great droughts); floods and hard winters tend to receive the most attention. Further data on weather and weather-related extreme events in Hungary are occasionally found in foreign narratives, mainly in the German-speaking areas and neighboring countries. Thus, while narratives are overwhelmingly important in medieval European climate-history research, an almost complete lack of weather-related information in the few high- and late-medieval narratives relating to Hungary and the Carpathian Basin means that a historian of the region has to use sources rarely used elsewhere. This is especially true for the period up to the mid-15th century, from which point other major European source types – particularly narratives and town accounts – assume a greater significance. Unique legal documentation of weather and floods: field surveys, perambulations and other charter types Charters are a unique medieval legal-administrative source type for climate history research in Hungary, which fact originates from the differences in legal documentation practices from most other parts of Europe. While charter production practices in high medieval times show no significant differences from other Central European types (East-Central European in particular), the documents are longer, more detailed, and often even annalistic from the 13th century. Nevertheless, it is the new royal dynasty in the early 14th century – the Italian Angevins, Charles Robert I in specific – that brings the real change, also responsible for the quantity boom of charters particularly from the 1320s (more details: Kiss 2019). Apart from the (donation) charter reports on famous political-military events also mentioning weather extremes, the most distinctive branch of charters contains field surveys and perambulations. In a field survey or perambulation charter the surveyors describe in detail processes and landscape features while walking along the boundaries, and point out obstacles – including weather- or flood-related – that hinder or obstruct them (example: Fig. 3). Moreover, these official reports were subject to further inspections that give further legitimation to the reliability and accuracy of their contents. Perambulators often made repeated attempts to complete their work; sometimes it had to be abandoned altogether because of extreme weather(-related) environmental conditions, for example, great floods, deep snow, or other extreme weather conditions, or a combination of such hindrances (e.g., Kiss, 2009, 2019). Although charters are key sources for weather research for the period between the 13th and early-to-mid-16th centuries, they are crucially important in any climate reconstruction for the 1320s-1420s (Fig. 2; see also Kiss, 2014, 2016, 2020). Nevertheless, other types of charter (e.g., prorogation and inquisitorial) can also contain weather-related entries, especially regarding travel and transportation. A particularly interesting, smaller group of charters is the royal donations: occasionally taking the form of narratives, with annalistic, detailed descriptions of important events or military campaigns, donation charters may also refer to the weather when it has an impact on the story. For example, information on the thawing of the snow and the subsequent downpour that led to the catastrophic defeat of the Mongols in Transylvania during the Second Mongol Invasion in 1285 was included in donation charters (see Kiss, 2014). Another important group of contemporary weather-related records is the legal documents issued by ecclesiastical jurisdictions. The canonization trial protocols of Saint Margaret, the Dominican nun (and royal princess), are a rare example: the official investigations – which were carried out by papal legates – took place in Buda(pest area) in 1276, seven years after her death, and contain the testimonies of over a hundred eyewitnesses. The most important miracle (as described by eyewitnesses) concerned two Danube ice jam floods that occurred in December 1267-January 1268; some of the witnesses also described sudden rain, muddy, inundated terrain, and gloomy weather. The church had its own legal system within (and beyond) the country: complaints against a member of the church, applications for a modification of ecclesiastical rights (e.g., establishing new parishes or changing boundaries), or inquiries into particular incidents were usually addressed to the local bishop or his administration. Avoiding the local bishop, some of these applications were directly addressed and sent to the pope, and are preserved in Avignon or Rome. Reaching their peak around the late 14th and the early 15th centuries, these sometimes contain references to weather or floods, while data on specific prayers and processions (rogation ceremonies) asking for rain are also known in one-one cases (e.g., Kiss, 2016, 2017). Official in the private and private in the official: (un)official letters and medieval memoires Official and/or private letters occasionally contain particularly important reports on weather extremes; these become more frequent in the 15th century. Their importance lies not only in their realistic and clearly dated eyewitness descriptions of these events but also in the information they provide on their social context and consequences. They offer insights into the private individual and/or popular perceptions of the events (in terms of religious belief or practical understanding). Authorship ranges from town citizens through medium- and high-status churchmen and noblemen up to kings and queens; occasionally, the letters of foreign legates provide interesting information on the subject. With rare exceptions, the letters show a rather practical, ‘survival mode’ approach to unusual/unexpected extreme weather. In addition to describing events, they usually focus on practical issues, for instance offering solutions and/or reorganizing subsequent activities. A good example is the extreme early ice-cover case that was described in a letter written by a Florentine legate in 1427. Ottoman troops had crossed the icy Danube near Belgrade in the south in mid-November (!) and caused great destruction in the region. In the meantime, the legate was waiting to cross the Sava River, which was impassable because of strong ice drifts (C. Tóth et al., 2020). Another interesting letter – written by the castellan to his lord, John of Hunyad – comes from the south-east (see Fig. 1), where a castle called Chery was swept away (!) by torrential waters just before mid-April 1443 (HNA DL 55253). No further details of this extraordinary event were supplied; the communication was essentially a request for a (good) carpenter who could supervise and help in rebuilding the castle. A third typical example is the letter of Queen Beatrix (HNA DL 98454) written in March 1496 in which she asked the salt chamber of Máramaros (Maramureş-Ro) about a large consignment of salt that never arrived. This was a result of the very low water level (‘lack of water’) of the Tisza River in 1494 – a famous drought year that was also described by Antonio Bonfini (Kiss, 2019, 2020; Kiss and Nikolić-Jakus, 2015). Amongst the private or semi-official documentation of the late medieval period, memoirs play a special role: not written for any orders, memoires provide down-to-earth accounts and allow their authors to express their own private views, understanding, and perception of events. They also present ample data on the physical-social environments in which the events described can be understood and interpreted. Written by an eyewitness of Italian origin in 1243, about the First Mongol Invasion (1241–1242), the Carmen miserabile (Szentpétery, 1999) is, without doubt, the most famous high-medieval memoir (or letter) of East Central Europe. The author, Master Rogerius, a clergyman (an archdean) living in (Nagy)Várad (Oradea-Ro), provides a shockingly realistic description of events: in addition to describing the Tatars and their massacres, and his own capture and successful escape, he includes precious information about the unusually cold winter, the deeply frozen Danube, and other weather-related environmental conditions that both helped and hindered the Mongols in their 1241-1242 invasion of the Carpathian Basin. Another, particularly interesting example is the memoire of Helene Kottanner – the wetnurse of the Hungarian king, Ladislaus V (1440-1458) – who provides us with detailed accounts of the weather during her travels in the central and western part of the country in the winter through summer of 1440 (Mollay, 1971). She writes about traveling in snow, moving through the Danube ice (almost disastrously), the rain and then heat, and the alternating dry and muddy roads in spring while crossing the Transdanubia, and presents a vivid description of a huge early-summer torrential downfall near Sopron on the western border of the country. Her daily/weekly observations parallel those of the Pressburg accounts (see Kiss, 2020a). Economic sources and the Pressburg chamberlain accounts (1434-1596) The medieval and early modern estate and manorial accounts, tithe rolls, and income and spending accounts of (mainly royal) towns occasionally contain weather data from the late 14th century. With one exception, until the end of the 15th century the reports tend to be sporadic, occasionally describing the consequences of a one-off rainfall event or period, expenses incurred in ice cutting in estate or town accounts, or a major flood event that resulted in partial tax relief, documented in a tithe account. With the exception of the extensive estate accounts of the Bishop of Eger from the beginning of the 1500s – which contain an unusually high number of weather-related references for certain years, including the drought and dearth years of 1506 and 1507 (E. Kovács, 1992; Kiss, 2020b) – perhaps the most important weather-related economic sources are town chamberlain accounts.  Fig. 4 The view of historical Pozsony/Pressburg (Bratislava-Sk) from the south with the Danube in the forefront (Braun and Hogenberg, 1594), and a sample page (AMB K5, 25) from the chamberlain accounts from 14 (Gregorian calendar: 23) December 1442, with reports on snow-cleaning, the freezing of the Danube and road preparation The present-day capital of Slovakia, Bratislava, historical Pozsony (capital of the Hungarian kingdom after 1541), Pressburg in German – the main language of the population and that of the local administrative documents in the 15th-16th centuries (1434-1596) – has by far the most detailed systematically presented town chamberlain accounts. Weather parameters such as precipitation (e.g., snow and rainfall), temperature (e.g., cold, freezing, various ice phenomena, Danube ice cover), strong winds, extreme weather (e.g., storms, torrential rain and flash floods) and related socio-economic information (e.g., high prices and transportation difficulties) are often mentioned when they have increased the cost of some of the everyday activities paid for by the town (Fig. 4). Because of its riverine position and the many kinds of riverine-related economic, travel, and transportation interests and activities in the Danube floodplain area and on the numerous islands, flooding and low water levels receive particular attention (Fig. 5).  Fig. 5 Example of medieval Danube floods and low flows mainly based on the Pressburg accounts, 1434–1535 (work in progress; source: AMB K1-86; see also Kiss, 2019, 2020a). Note three anomalous periods: the 1430s-early/mid-1440s (with both floods and low flows) marking the early Spörer solar minimum, the late 1470s–early 1500s and a period from the mid-1520s – coinciding with the mid- (and late?) Spörer minimum. Two extraordinary intensity events highlighted; heights of the 1501 ‘deluge’ remain unreported Although in Central Europe one-one flood and grain-harvest-based temperature reconstructions have already used data from town accounts (e.g., Wels, Austria: Rohr, 2006; Basel, Switzerland: Wetter and Pfister, 2011), the present research is novel because it contains not only one-one systematic chapters or phenology-/flood-related data types extracted from individual town accounts, but also a systematic survey of the entire manuscript series containing all direct and indirect information on the weather and extreme weather-related conditions. The accounts are of great importance because they cover almost the entire Spörer Minimum (and beyond), an unusually long period of low solar activity. With only a few (mainly half-half year) gaps, the accounts straddle the late medieval and early modern periods, during which the administrative system and the methods of recording income and expenditure and related information remain mainly the same. Because of the frequency and high-resolution of detail they contain, they are indispensable for pinpointing Danube flood events. Allowing the extension of the annual-/seasonal-resolution flood (frequency, intensity, seasonality) reconstruction of a major European 500-year river flood series with almost a hundred year, it is one of the series of inevitable importance in large-scale multi-centennial flood analyses and reconstructions (see e.g. Blöschl et al., 2020).  Fig. 6 Example of Danube-ice-related information between 1434 and 1535 in the Pressburg accounts (work in progress; source: AMB K1-86). Colors: systematic mentions of Danube ice-related phenomena and activities. 3-scaled ice intensity indices (mixed accounts): 1=sporadic mention of ice over the winter: 1-3 cases; 2=average mention of ice (ca. 4-6), also in multiple place and time; 3=ice frequently mentioned and in great spatial, temporal (and vertical) extent. Note two anomalous periods around the 1430s-1440s and the 1480s-1510s marking the hard winters of the early and mid-Spörer Minimum, and the cold winters of the (early) 1530s Within the chamberlain accounts almost all chapters contain weather-related information, but perhaps the most important source of information comes from the ferry and bridge accounts, where data is available on daily and weekly basis (bridges existed here over the entire Danube from the early 1430s). Furthermore, in separate chapters, references were regularly made to ice being cut in the town moat, snow-clearing works around the town hall, ships, and bridges, and floods (data included in Figs. 5, 6). The early parts of the accounts also contain a chapter that refers to payments to town messengers who sometimes had to endure harsh weather conditions, flooding, or the dangers associated with crossing the ice-covered Danube to carry messages to other areas of Hungary or Austria. Individual extreme events, sometimes real ‘delicacies’, occasionally are also described: for example, a case of mass soil erosion that occurred in summer 1458 when it appears that the earth on the hillside(s) over and around the town was washed down by torrential rain(s). On that occasion, the town paid to clean the streets and some of the roads of the sediment (maybe also of a Danube flood?; source: AMB K26). Although such expenditure is often listed in separate chapters, weather-related information can be found in all kinds of payments, most especially those of the (longest) category: the miscellaneous expenses (e.g., Kiss, 2019, 2020a). Animated rivers, rainfall-triggered erosion, and the mid-winter blossoming of an almond tree: the brave new trend of humanism The Italian Renaissance spread to and blossomed in Hungary from the second half of the 15th century; referring to real-life extreme weather(-related) events, the perception of nature often appeared in humanist writing. Humanists such as Janus Pannonius (the Bishop of Pécs, who studied in Italy) and the Italian Antonio Bonfini (who was living in Hungary at the time) used weather and weather-related phenomena in their allegories, the details of which help us to date the occurrence of unusual events such the mid-winter blossoming of an almond tree, winter snow-cover, or a great flood. In addition to his descriptions of significant late 15th-century droughts, Bonfini, in the Rerum Ungaricarum Decades (Fógel, 1941), refers to the flood that occurred after the death of King Matthias - which is also mentioned in Austrian sources and the Pressburg accounts (see Fig. 5) – where the Danube appears as a protective, living entity. A real ‘delicacy’ is the poem De inundacione of Janus Pannonius who describes great torrential rainfall and a subsequent flood event involving the largest rivers in the South Carpathian Basin, and connects the event to the arrival of a famous comet (V. Kovács, 1972). His dating of the event to the arrival of a famous comet – reported in Europe and all over the Northern Hemisphere (e.g. Hasegawa and Nakano, 1995; Kak, 2003, Martínez and Marco, 2016; de Carvalho, 2021) in autumn 1468 – has made it possible to identify and connect this reference to a Danube flood reported around the same time in the Pressburg accounts. In this poem, as an allegory of the approaching apocalypse, Janus Pannonius presents a strikingly realistic ‘environmental catastrophe’ domino-model based on the cumulative effects of heavy rainfall, floods, subsequent soil degradation and mass erosion, the aggregation of infertile river sediments, the multiannual destruction of grain and grapevine harvests (and stocks) that result famine (see Kiss, 2019). References

AMB (Archiv hlavneho mesta SR Bratislavy/Archiv der Hauptstadt der SR Bratislava). Magistrát mesta Bratislavy (AMB-A/XXIV.1): Komarna kniha/Kammerbuch: K1–86 (1434–1535) Blöschl, G., Kiss, A., Viglione, A., Barriendos, M., Böhm, O., Brázdil, R., Coeur, D., Demareé, G., Llasat, M.C., Macdonald, N., Retsö, D., Roald, L., Schmocker-Fackel, P., Amorím, I., Bĕlinová, M., Benito, G., Bertolin, C., Camuffo, D., Cornel, D., Doktor, R., Elleder, L., Enzi, S., Garcia, J.C., Glaser, R., Hall, J., Haslinger, K., Hofstätter, M., Komma, J., Limanówka, D., Lun, D., Panin, A., Parajka, J., Petrić, H., Rodrigo, F.S., Rohr, C., Schönbein, J., Schulte, L., Silva, L.P., Toonen, W.H.J., Valent, P., Waser, J. and Wetter, O., “Current European flood-rich period exceptional compared with past 500 years,” Nature, 583, 2020, p. 560–566 Braun, G. and Hogenberg, F., Civitates Orbis Terrarum. Liber Quartus. Cologne, Bertram Buchholtz, 1594, map 44 C. Tóth, N., Lakatos, B. and Mikó, G., Zsigmondkori Oklevéltár. Vol. 14: 1427. A Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár Országos Levéltárának kiadványai 2, Forráskiadványok 59. Budapest, Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár, 2020 de Carvalho, H. A., An Astrologer at Work in Late Medieval France. The Notebooks of S. Belle. Time, Astronomy, and Calendars Vol. 11. Brill, 2021, p. 372–373 E. Kovács, P., Estei Hippolit püspök egri számadáskönyvei 1500-1508. Eger, Heves Megyei Levéltár, 1992 Fógel, J., Iványi, B. and Juhász, L. Antonius de Bonfinis: Rerum Ungaricarum Decades. Vols. 3 and 4. Leipzig–Budapest, B. G. Teubner–Budapest K. M. Egyetemi Nyomda, 1936, 1941 Hasegawa, I., Nakano, S., “Periodic comets found in historical records,” Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan, 47, 1995, p. 699–710 Hung. Nat. Arch. (HNA) = Hungarian National Archives, Collection of Medieval Documents DL 55253, 57079, 98454 Kak, S., “Three interesting 15th and 16th century comet sightings Kashmiri chronicles”, History and Philosophy of Physics, 2003, physics/0309113 Kiss, A., “Floods and weather in 1342 and 1343 in the Carpathian Basin,” Journal of Environmental Geography, 2/3–4, 2009, p. 37–47 Kiss, A., “Weather and weather-related environmental phenomena including natural hazards in medieval Hungary I: Documentary evidence on the 11th and 12th centuries,” Medium Aevum Quotidianum, 66, 2013, p. 5–37 Kiss, A., “Weather and weather-related natural hazards in medieval Hungary II: Documentary evidence on the 13th century,” Medium Aevum Quotidianum, 68, 2014, p. 5–46 Kiss, A., “Weather and weather-related natural hazards in medieval Hungary III: Documentary evidence on the 14th century,” Medium Aevum Quotidianum, 73, 2016, 5–55 Kiss, A., “Droughts and low water levels in late medieval Hungary II: 1361, 1439, 1443-4, 1455, 1473, 1480, 1482(?) 1502-3, 1506: documentary versus tree-ring (OWDA) evidence,” Journal of Environmental Geography, 10/3–4, 2017, p. 43–56 Kiss, A., Floods and Long-Term Water-Level Changes in Medieval Hungary. Heidelberg–New York, Springer, 2019 Kiss, A., “Weather and weather-related natural hazards in medieval Hungary IV: Documentary evidence from 1401-1450,” Economic and Eco-history, 16, 2020a, p. 9–54 Kiss, A., “The great 1506-1507 drought and its consequences in Hungary in a (Central) European context,” Regional Environmental Change, 20, 2020b, No. 50 Kiss, A. and Nikolić-Jakus, Z., “Droughts, dry spells and low water levels in medieval Hungary (and Croatia) I. The great droughts of 1362, 1474, 1479, 1494 and 1507,” Journal of Environmental Geography, 8/1-2, 2015, p. 11–22 Martínez, M.J. and Marco, F.J., “Fifteenth century comets in non-astronomical Catalan manuscripts,” Journal of Catalan Studies, 2016, p. 51–65 Mollay, K. (ed.), Die Denkwürdigkeiten der Helene Kottannerin (1439-1440), Vol. 2, Vienna, Österreichischer Bundesverlag, 1971 Rohr, C. “Measuring the frequency and intensity of floods of the Traun River (Upper Austria), 1441–1574,” Hydrological Sciences Journal, 51/5, 2006, p. 834–847 Szentpétery, I., Scriptores Rerum Hungaricarum. Tempore ducum regiumque stirpis Arpadianae gestarum, Vol. 2, Budapest, Nap Kiadó, 1999 V. Kovács, S., Janus Pannonius munkái latinul és magyarul. Janus Pannonius élő emlékezetének halálának ötszázadik évfordulója alkalmából/Jani Pannonii opera latine et hungarice. Vivae memoriae Iani Pannonii quingentesimo mortis suae anniversario dedicatum, Budapest, Tankönyvkiadó, 1972, p. 371–381 Wetter, O. and Pfister, C., “Spring-summer temperatures reconstructed for northern Switzerland and southwestern Germany from winter rye harvest dates, 1454–1970,” Climate of the Past, 7, 2011, p. 1307-1326

0 Comments

|

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed