|

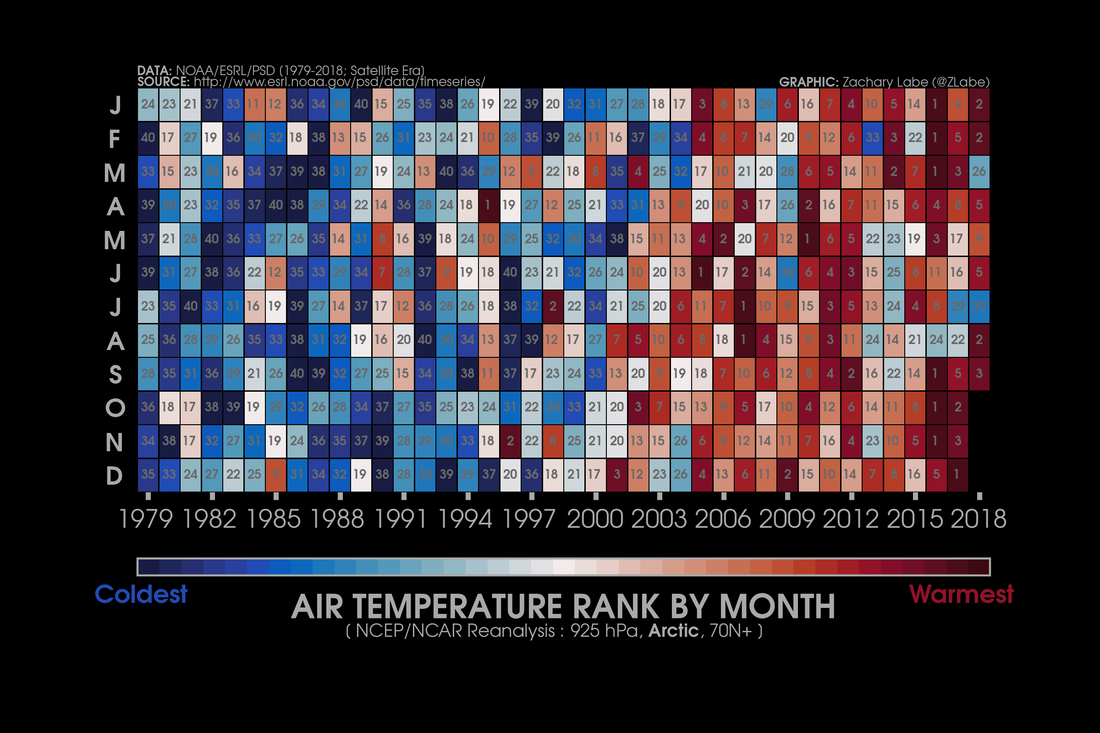

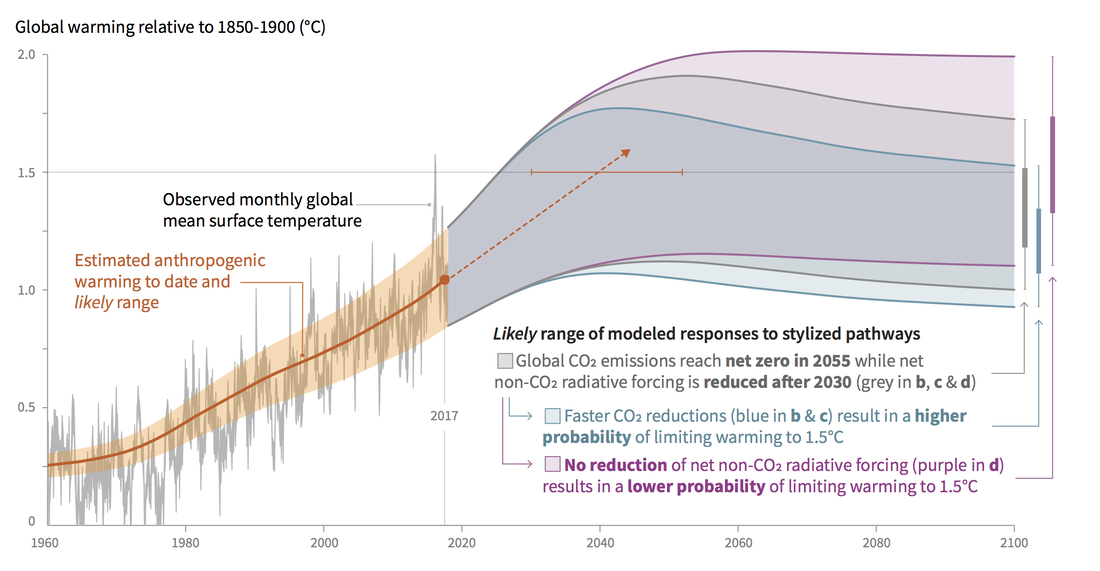

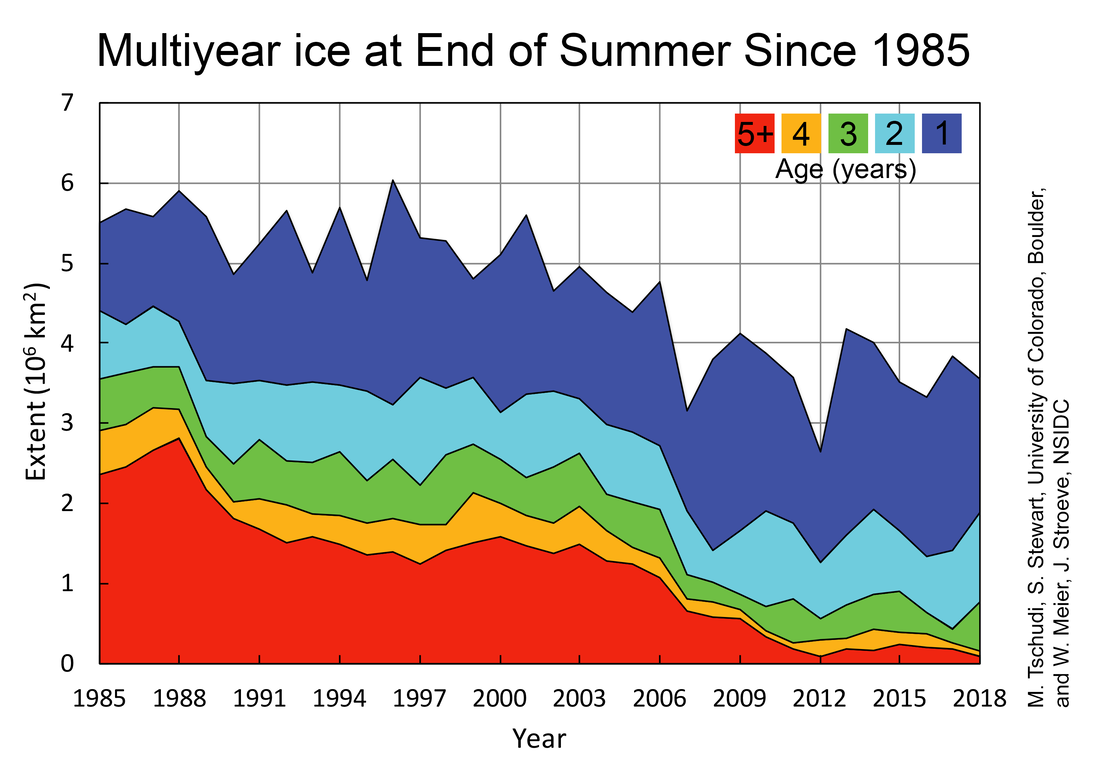

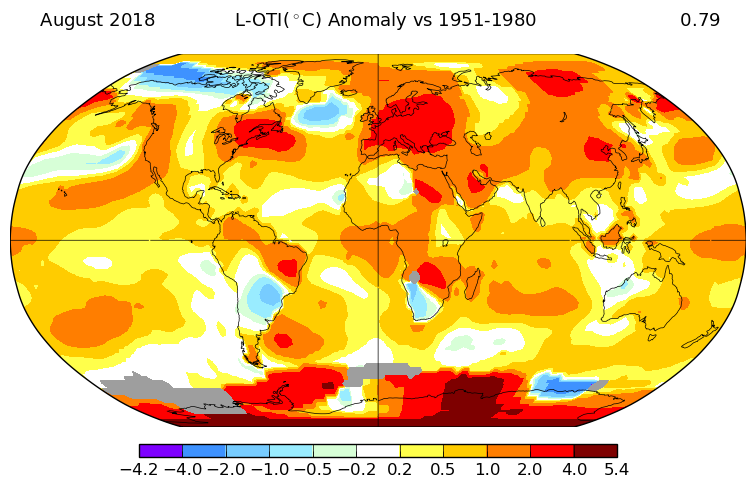

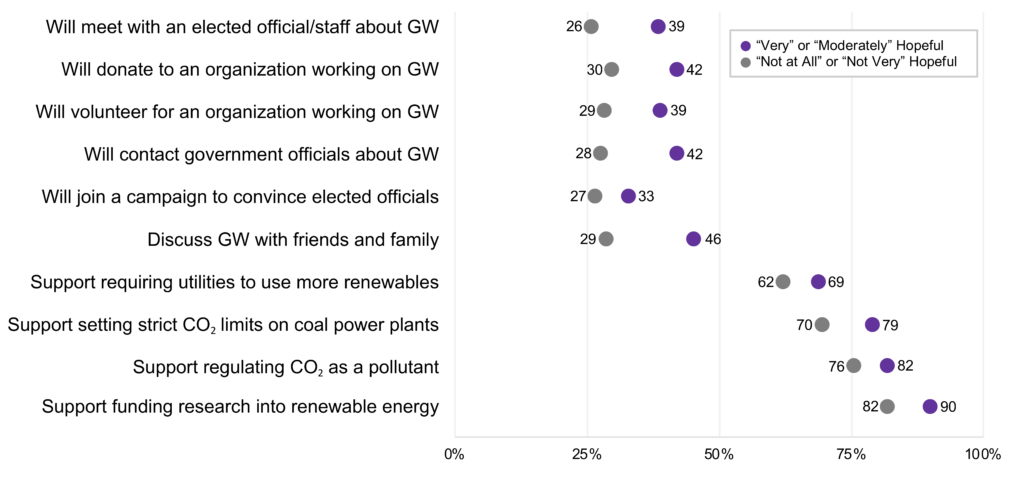

Dr. Dagomar Degroot, Georgetown University International climate change agreements have long aimed at limiting anthropogenic global warming to 2°C Celsius, relative to “pre-industrial” averages. Yet in early 2015, more than 70 scientists contributed to a report that warned about then-poorly understood dangers of warming short of 2° C. Several months later, Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) met in Paris and reached what seemed to be a promising agreement that aimed at keeping global warming to “well below” 2° C. The Paris Agreement invited the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to prepare a special Assessment Report on the consequences of, and means of avoiding, warming on the order of 1.5° C. The IPCC accepted the invitation in 2016. This week, it published its report, together with a short summary for policymakers. In it, 91 scholars from 40 countries summarize the results of more than 6,000 peer-reviewed articles on climate change. The published report still captured headlines and provoked justified alarm. Here’s what struck me as I read through it this week. The Importance of 0.5° CThe new assessment report is really all about half a degree Celsius. Since the world has now warmed by roughly one degree Celsius since a 1850-1900 baseline, only half a degree Celsius separates us from 1.5° C of warming, which in turn is of course only half a degree removed from the infamous 2° C threshold previously emphasized by the IPCC and the UNFCCC. So, what difference does 0.5° C make? It depends on the perspective you take. The new report shocked many by predicting that some of the profound environmental transformations long anticipated with 2° C warming, relative to the nineteenth-century baseline, would be well underway with just 1.5° C warming. By 2100, for example, sea levels could rise by up to 0.77 meters if temperatures increase by no more than 1.5° C, which may only be around 0.1 meters lower than the level they would reach with 2° C warming. Worse, it now seems that marine ice cliff instability in Antarctica and the irreversible collapse of the Greenland ice sheet – two frightening scenarios that could each raise global sea levels by many more meters and set off additional tipping points in the climate system (see below) – could be triggered by just 1.5° C warming. Perhaps 90% of the world’s coral reefs could be lost with 1.5°C warming, compared to every reef in a 2° C world. In one sense, there seems to be a huge gulf between where we are now and where we’d be with another half-degree of warming, and comparatively little difference between a 1.5° C and a 2° C world. Yet in other, critically important ways, there could be an equally big gap between the 1.5° C and 2° C scenarios. Of 105,000 species considered in the report, three times as many insects, and twice as many plants and animals, would endure profound climatically-determined changes in geographic range in a 2° C world, relative to a 1.5° C world. A threefold increase in the terrestrial land area projected to change from one ecosystem to another also seperates the 1.5° C and 2° C worlds. The importance of just half a degree Celsius is particularly clear at local and regional scales. Warming is greater on land than at sea, and much greater across the Arctic. In cities, urban heat islands double or even treble global warming trends. In many regions, extreme weather events – droughts, torrential rains, heat waves and even cold snaps – are now much more likely to occur than they once were. Superficially modest trends on a global scale can mask tremendous shifts in local or regional weather. The critical importance of warming on the order of just half a degree Celsius for ecosystems around the world invites us to revisit some of the more controversial claims made by climate historians about the environmental impacts of past climate change. There is, of course, a range of natural climatic variability that most ecosystems can accommodate, and we are on the verge of leaving that range across much of the Earth, if we have not left it already. Yet it now seems painfully clear that even small fluctuations in Earth’s average annual temperature can have truly profound ramifications for the regional or local ranges and life cycles of plants, animals, and microbes. Risk, Uncertainty, and ScaleBack to the difference between 1°, 1.5°, and 2° C warming. Perhaps the most alarming part of the new assessment report – one seemingly lost on many environmental journalists – is what it says about the value of the whole project of establishing numbers that become touchstones in climate change discourse. Beginning well before 2015, climate scholars pointed out that attempts to emphasize the danger of 2° C warming risked creating the false impression, among policymakers and the public, that the worst impacts of climate change would suddenly unfold only after Earth passed that threshold. I’d wager that for most people, the 2° C limit still seems like a distant threat, one we will eventually face only if we don’t gradually reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Yet the new report confirms that the 2° C threshold was all along an arbitrary standard, one that did not really convey the nature of the threat we face. It is now plain that we will not only trigger vast and irreversible changes to Earth’s climate system with 1.5° C warming, but worse: we have already engaged some of them, and we may unlock more in coming years. Nature, unfortunately, cares little for our nicely rounded numbers. There’s more. Even before its release, some climate scientists and activists criticized the new report for understating the extent of present-day warming, and more importantly: ignoring the so-called “fat tail” threat of runaway warming triggered by positive feedbacks, or “tipping points,” buried within the climate system. Of these feedbacks, the best known is probably the ice-albedo feedback, where modest warming melts bright sea ice that normally bounces sunlight back into space, replacing it with dark water that absorbs solar radiation, contributes to more warming, more melting, and so on. Another well-known feedback involves methane that now lies buried in Arctic permafrost and frozen seabed sediment. Warming is already melting tons of methane into the atmosphere, where it traps far more heat than carbon dioxide. Again: warming will lead to more melting, more warming, and so on. These feedbacks have historically converted relatively minor sources of warming or cooling into profound climatic trends. Yet scientists don’t know precisely how all such feedbacks work, or when exactly they are triggered. If we’re lucky, we won’t trigger most of them at all, not even if we reach that 2° C threshold. Yet it’s also possible that we have already set some of them in motion, in ways that will irreversibly lead us to runaway warming. In that case, our children – or our children’s children – will have to survive a “hothouse” world, one fundamentally different from our own. This brings us back to the issue of risk and probability, which the IPCC’s scientists stress in every assessment reports. The IPCC expresses uncertainty using the terms “confidence” and “likelihood,” and it is very important to decode these terms in order to understand the new assessment report. In it, the terms “very low,” “low,” “medium,” “high,” and “very high” confidence all refer to the confidence the report authors have in key findings. Their level of confidence reflects both the quality, quantity, and type of evidence used to support those findings, and the extent to which different lines of evidence agree with the findings. In the report, the terms “exceptionally unlikely,” “extremely unlikely,” “very unlikely,” “unlikely,” “about as likely as not,” “likely, “very likely,’ and “extremely likely” all refer to the statistical probability of outcomes actually happening, based in part on the findings. Unfortunately, these definitions are buried on page 40 of the first chapter of the new assessment report. Yet they make it impossible to conclude, as so many journalists have written, that the new report predicts what will happen in the future. Using such language plays into the hands of climate change deniers, who rightly point out that nobody can predict the future with certainty. Climate scientists, of course, know that better than most, which is why they always attempt to qualify and quantify their predictions. Climate historians also deal with probability. As I point out in a forthcoming article, we can never really reconstruct the local or regional manifestations of climate change with perfect certainty, nor can we be completely sure of local connections between climatic trends and human or animal behavior. Some of the most interesting relationships we can discern are among the least documented, especially once we get away from the usual European or Chinese focus of most climate historians. At its best, climate history therefore deals explicitly with risk and uncertainty by qualifying its major findings. Other historians tend to rebel against such qualifiers. More than one peer reviewer, for example, has told me to be more authoritative, to forcefully express that climate change directly caused humans to do something in the past. To these historians, qualifiers communicate the kind of weak uncertainty that seems to suggest that an argument is not well grounded on solid scholarship. These criticisms come from the practice of traditional historical scholarship, where documents seem to communicate exactly what happened to whom, and when. Yet when we work with different kinds of sources, from natural archives, those relationships cannot always be clearly or simply established. The more, and more diverse, information you have, the more uncertain the past can become. Still, abundant information from many natural and human sources can also provoke questions, and suggest relationships, that traditional historians have not imagined. The best documented and seemingly most certain version of the past, in other words, isn't always the most accurate. A Determined Future (and Past?)The new IPCC report also abounds with exactly the kind of sweeping statements that historians – myself included – have attacked in the past. In a brilliant 2011 article I often ask my students to read, Mike Hulme criticizes how the predictive natural sciences have promoted a new variant of the climate determinism many Europeans once used to explain the expansion of western empires. Because climate change can be predicted more easily than social change, Hulme argues, climate science has promoted a kind of climate reductionism that “downgrades human agency and constrains the human imagination.” Surely, the human future will not be crudely determined by climatic trends. And yet, the IPCC concludes that climate change will probably exacerbate poverty, provoke catastrophic migration, impede or annihilate economic growth, amplify the risk of disease, and, in short, sharply undermine human wellbeing, especially for “disadvantaged and vulnerable populations, some indigenous peoples, and local communities dependent on agricultural or coastal livelihoods.” While there will be ways for communities and societies to adapt, the IPCC’s summary for policymakers finds that “there are limits to adaptation and adaptive capacity for some human and natural systems” in even a 1.5° C world. Warming, in short, will likely provoke human suffering. Should we be skeptical of such claims? As usual: it’s complicated. While historians like to emphasize complexity and contingency in narratives of the past, scientists search for patterns in complex systems that permit predictive models. Many historians therefore feel uncomfortable when asked to anticipate the future in light of the past, and that discomfort is partly to blame for the unfortunate absence of historical scholarship in the new assessment report. Of course, scientists have no such problem. Their models can indeed be deterministic – by necessity, they only consider so many variables – yet they still provide some of our best perspectives on what the future might have in store. With that said, it's important to again stress that many of these models should be taken as estimates of what might happen in our future. They cannot tell us what will actually unfold. History does teach us that the human story involves both steady trends and sudden leaps: technological breakthroughs, revolutions, and the like. It is simply wrong to conclude that even 2° C warming will make the world a more impoverished, more violent place, as some assume. Older predictions of “peak oil,” for example, or a “population bomb” have not (yet) come to pass, partly because individuals and institutions responded creatively, on many different scales, to menacing trends. The new assessment report actually describes the kind of action that would help state and non-state actors confront the challenge of climate change (spoiler alert: it’s not geo-engineering). People are not passive, static victims in the IPCC’s assessment, as they tend to be in reductionist literature. Yet even if the wise policies recommended by the IPCC are ignored, we cannot predict or quantify exactly what the future has in store for humanity. But now, back to those controversial claims made by climate historians. Critics have accused some of the more ambitious books in climate history – authored by the likes of John Brooke and Geoffrey Parker, for example – of crude determinism for suggesting that past climatic fluctuations on the order of just half a degree Celsius unleashed disaster for societies around the pre-modern world. Indeed, some calamities that climate historians have blamed on climate change had many alternate or additional causes, and most coincided with examples of communities and societies successfully weathering climate change. Yet the scale of social disruption predicted by the IPCC in a world just a little warmer than our own does invite us to consider whether the fates of pre-industrial societies were not more closely connected to climatic trends than most historians and archaeologists have allowed. Both environments and societies, in other words, seem more vulnerable to even slight climatic fluctuations than we had imagined. The Popular ResponseIn the wake of the new report, articles in popular media and discussions in social media have predictably focused on how its findings should be communicated. Should climate communicators try to drum up fear, or should be we inspire hope? Hope does seem to be more useful emotion in motivation public engagement on global warming. Yet recently, many scholars have actually moved beyond this question. A 2017 article in the journal Nature, for example, concludes that climate change messages should be carefully calibrated to their audience. Neither hope nor fear will motivate everyone; in fact, a catchall message that relies on either emotion will likely provoke the opposite of the desired response in a sizable part of the population. This is hardly surprising: political operatives and advertisers have known for years that the best messages are highly targeted. Some news articles have stressed what individuals can do in order to lower their personal carbon emissions. Many scientists and environmentalists have responded by arguing that only government policy can begin to address climate change on the scale we need. By stressing personal accountability, some argue, journalists shift attention from the real climate culprits: the big corporations and well-funded political interests with a stake in the fossil fuel economy. As in most such debates, both sides have valid points. Clearly, we should all aim to limit our emissions while at the same time becoming politically motivated as never before. We will need to fundamentally transform our economy and our politics – quickly! – if we are to confront the challenge of climate change. How we do this, and what it will mean for us personally, is something all of us will need to sort out soon. Those of us who have chosen to remain above the political fray will need to re-evaluate that decision. Some of the first news articles about the IPCC's new report included commentaries on the need for journalists to make climate change the biggest story they cover. I wrote an article to that effect during the 2016 election, and sent it to the editors of the New York Times. Predictably, there was no response. And now, even in the wake of hurricane Michael’s rapid intensification and calamitous landfall, climate change has already moved off the front pages of many newspapers. Politicians in the United States and elsewhere have already brushed off the IPCC’s urgent warnings. One wonders: will the new report really change anything? Or will the capitalist dynamics behind our media outlets and political processes derail the changes we so urgently need to make? Ultimately, it’s clear that nobody and nothing will rise to save us from our fate. Those of us who understand the science behind climate change need to do more than communicate. Now, we need to actively be part of the solution. We need to act. Recommended Reading |

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed