|

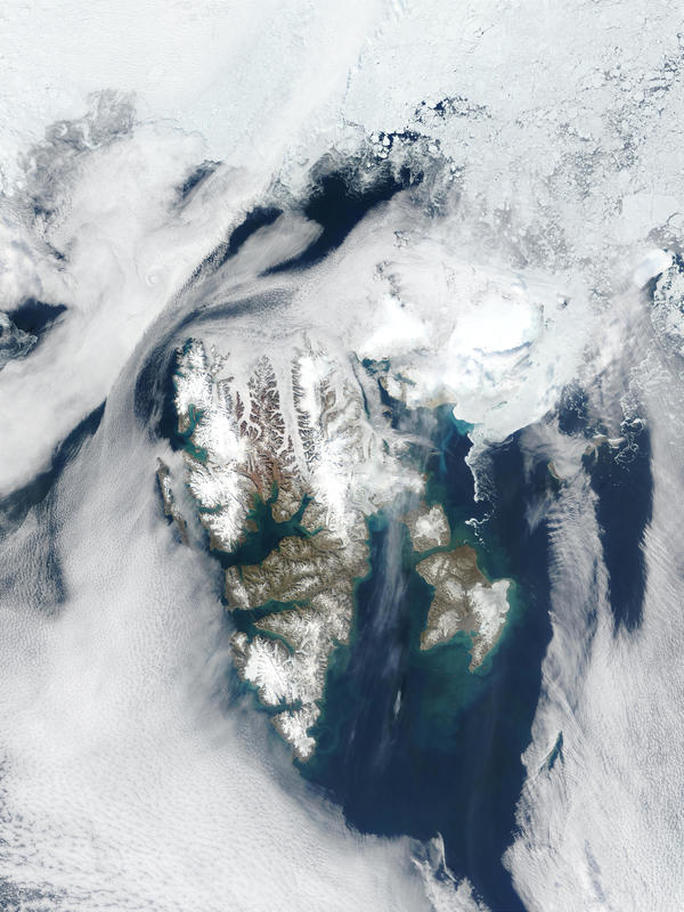

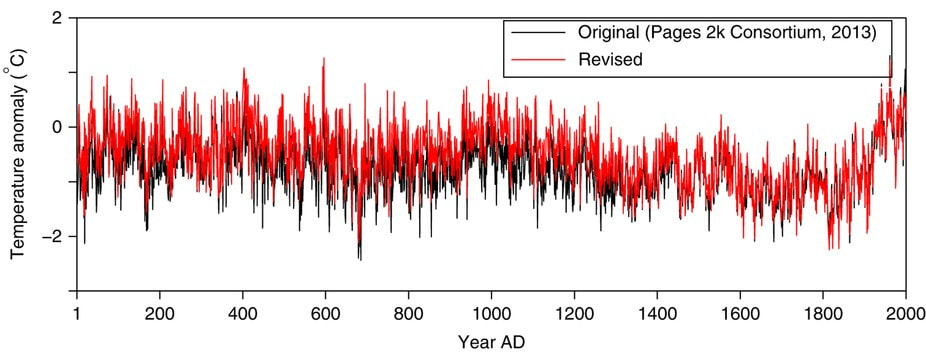

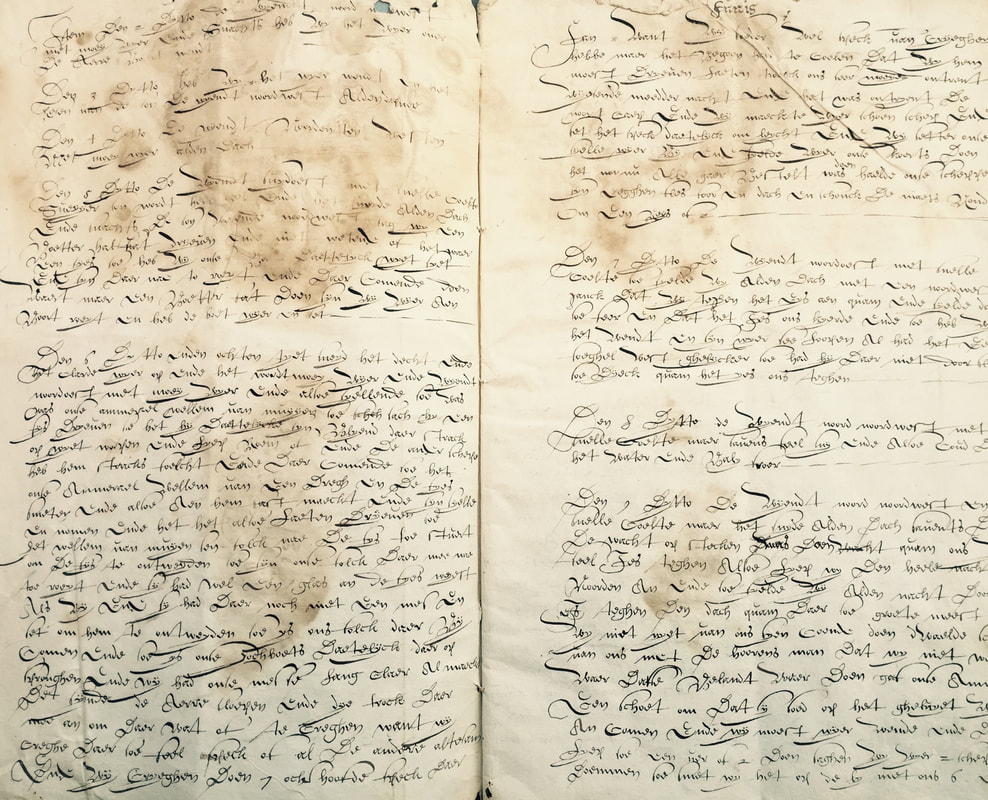

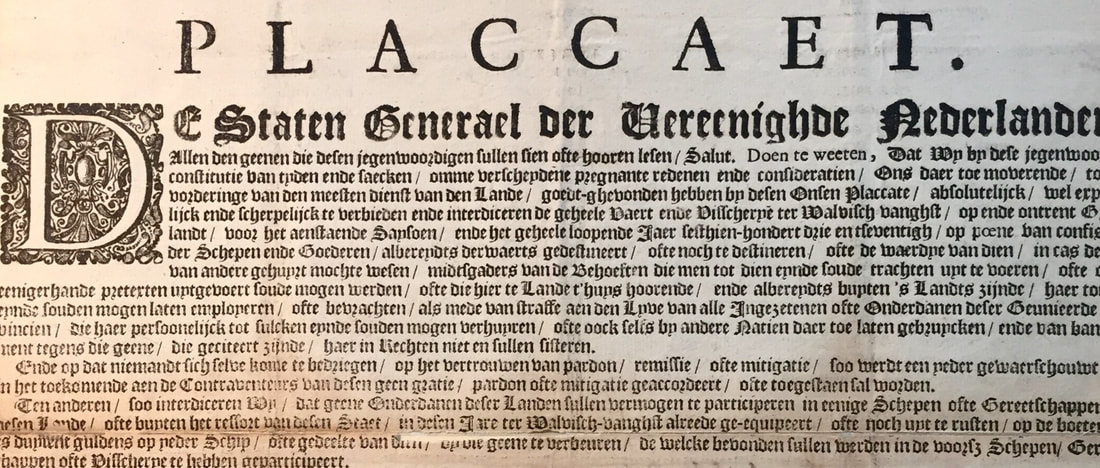

In article after article, academics, policy analysts, and journalists have told a similar story: climate change, by melting Arctic ice, is unlocking resources that could soon trigger war in the far north. They argue that the race to extract the vast reservoirs of oil and natural gas that lie under the vanishing ice – up to a quarter of the world’s undiscovered fossil fuel reserves, by some estimates – will likely provoke hostilities between Russia, the United States, and other nations with claims to the bonanza. The overall failure of early drilling efforts in the Arctic, it seems, is of little consequence. These claims add a new twist to a vast and growing body of scholarship that links climate change to conflict. Academics working in this area often begin their work by showing that past climate changes reduced – rather than increased – the regional availability of some crucial resource, such as water, or grain, or fish spawning grounds. They then use diverse methods to trace the destabilizing social and political consequences of these resource shortages. Environmental historians, for example, have argued that falling temperatures and changing precipitation patterns in the seventeenth century led to poor grain harvests and famines that provoked rebellions in diverse societies the world over. More controversially, scholars in many disciplines have linked human-caused global warming to droughts that encouraged migration and ultimately conflict in twentieth-century sub-Saharan Africa. Far less attention has been directed at the ways in which more abundant resources might incite violence either within or between states. In fact, those who make claims about the inevitably more violent nature of the future Arctic have rarely thought to consider the history of climate change and conflict in the far north. Yet violence in the Arctic has long coincided with volcanic eruptions and fluctuations in solar activity that altered regional temperatures and in turn the availability of crucial resources. In the early seventeenth century, for example, the Arctic cooled sharply and then warmed slightly just as Europeans discovered, hunted, and fought over bowhead whales off Spitsbergen, the largest island of the Svalbard archipelago. Oil, bones, and baleen from bowheads became crucial resources for the economies of England and the Dutch Republic. Diverse manifestations of climate change in the Arctic and Europe influenced how easy bowhead whales were to hunt, the profits that could be fetched by their oil, the proximity of whalers to one another, and the ability of whalers to reach the far north. Skirmishes within and between whaling companies operating from rival European nations reveal that climate change can affect both the causes and the conduct of conflict in diverse ways, even in environments it transforms on a vast scale. There is nothing inevitable or simple about the ways in which climate change influences human decisions and actions. This history would be hard to investigate without new climate reconstructions compiled by scholars in many different disciplines, using many different sources. In 2014, researchers drew from natural and textual sources to create a sweeping new reconstruction of average Arctic air surface temperatures over the past 2,000 years. It confirms that the Arctic was overall very cold in the seventeenth century, but also that it warmed slightly towards the middle and end of the century. Temperatures in the Arctic therefore roughly mirrored those elsewhere in the Northern Hemisphere during the chilliest century of the “Little Ice Age,” a cooler climatic regime that endured for roughly six centuries. The extent and distribution of sea ice in the Arctic – the most important environmental condition that whalers coped with – would have responded to even subtle changes in average annual temperatures. Yet these very big trends do not tell us exactly how climate change transformed environments around Svalbard. Local temperature trends do not always precisely mirror regional or global developments, and anyway the distribution and extent of Arctic sea ice registers more than just the warmth or chilliness of the lower atmosphere. Ice core and model simulation data both suggest that air surface temperatures around Svalbard were quite cool in the early seventeenth century and somewhat warmer in the middle of the century, at least in summer. Lakebed sediments, by contrast, suggest that glaciers across Svalbard actually retreated beginning in around 1600 owing to changes in precipitation, not temperature, which may have reduced the local frequency of storms that can break up sea ice. Moreover, sea surface temperatures – which also influence sea ice – were quite warm off the west coast of Spitsbergen, the largest island of the Svalbard archipelago, for much of the seventeenth century, although they were very cold off the northern coast. Overall, it seems safe to conclude that, in the summer, temperatures around Svalbard roughly mirrored those of the broader Arctic in the seventeenth century. Warmer currents may have brought more nutrients to the region and probably reduced the extent of local sea ice, although a reduction in storm frequency would have preserved the ice that was there. In any case, most Arctic sea ice melts in the summer before reaching its minimum annual extent in the fall, which means that summer weather and currents had the greatest impact on the extent of ice in the Arctic north of Europe. Because sea ice retreated from Svalbard in the summer, it was also the crucial season for whaling. If the local consequences of global climate changes can be counterintuitive – that warming current off Spitsbergen, for example – so too can human responses. One might assume that climatic cooling would have dissuaded explorers, fishers, and whalers from entering the Arctic. Instead, European sailors found and then started exploiting the environments on and around Svalbard in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, just as volcanic eruptions led to arguably the coldest point of the Little Ice Age in the Northern Hemisphere. In previous work, I have shown that climate changes in this period interacted with local environments to leave just enough sea ice in the Arctic north of Europe to redirect expeditions in search of an elusive “Northern Passage” to Asia. Dutch and English sailors struggling to find a way through the ice ended up discovering Spitsbergen and the many bowhead whales off its western coast. Bowheads are relatively docile, float on the surface when killed, and have very thick blubber that can be turned into oil. Beginning in 1611, they started attracting Dutch, English, and Basque whalers. Other scholars have argued that cooling in the early seventeenth century led bowhead whales to congregate along more extensive sea ice near Spitsbergen, which made them easier to hunt for whalers. By contrast, whales dispersed as sea ice retreated in the warmer middle of the seventeenth century, which made them harder to hunt. There does seem to be a statistically significant correlation between ice core reconstructions and model simulations of summer temperatures around Spitsbergen on the one hand, and the annual whale catch on the other. Iñupiat whalers consulted by our own Bathsheba Demuth, however, report that bowheads in the Berring Sea are not social enough to gather in huge groups. Perhaps bowhead culture was different in the Atlantic corner of the Arctic when whale populations were much higher than they are today. The apparent correlation between surface air temperatures and the whale catch around Spitsbergen provides our first point of entry into relationships between climate change and conflict in the far north. From the first years of whaling around Spitsbergen, two companies – the Dutch Northern Company, and the English Muscovy Company – emerged as the leading players in the Arctic whaling industry. The governments of England and the Dutch Republic had granted these companies monopolies on whaling operations, but they were resented by merchants and mariners who preferred to operate independently. After around 1625, as bowhead whales dispersed amid warming temperatures, competition between Dutch whalers devolved into piracy. Many conflicts involved whalers who sailed either for the Northern Company or for themselves, although even some Company whalers hid the best hunting grounds from one another. In these circumstances, the governing body of the Dutch Republic rescinded the monopoly of the Northern Company in 1642. From the beginning, competition between English whalers assumed an even more brutal character. The Muscovy Company took an uncompromising stance towards English interlopers, who responded in turn. In 1626, for example, whalers aboard independently-owned vessels destroyed the Company’s station at Horn Sound, Spitsbergen, after they had been harassed by Company ships. Not surprisingly, petitions submitted to the English Standing Council for Trade in 1652 reveal that small groups of English merchants also sought to overturn the monopoly of the Muscovy Company. Individual merchants insisted that the Company could not adequately “fish” the territories over which it held a monopoly. The Company responded that whalers in the employ of those merchants had interfered with the activities of its sailors and stolen whales they had killed. Warming temperatures that reduced the extent of pack ice and encouraged whales to disperse may well have encouraged competition and conflict between whalers belonging to the same nationality. Bizarrely, the whaling industry also responded to fluctuations in the supply of rape, linseed and hemp oils, which were less smelly substitutes to whale oil for fueling lamps or manufacturing soap, leather, or wax. Temperature and precipitation extremes that reduced the supply of vegetable oils naturally also increased the price of whale oils in the Dutch and English economies, and thereby the profitability of whaling. In the context of the Little Ice Age, the 1630s in particular were relatively warm across the Northern Hemisphere. The trusty Allen-Unger commodity database tells us that the price of linseed oil in Augsburg, for example, dropped sharply as average annual temperatures increased. Even the price of lamp oil – which would have also registered the price of whale oil – fell modestly in the same period. Could whalers in the 1630s and 1640s have vied with monopolistic companies just climate change both reduced the supply of their resource and increased its profitability? We can sketch these relationships by mixing and matching different statistics from natural and textual archives. Detailed qualitative accounts written by whalers, however, reveal that climate influenced conflict in more complicated ways during the first decade of the Svalbard whaling industry. In that decade, whalers from several European nations – most importantly England and the Dutch Republic – employed experienced Basque whalers to kill bowhead whales, strip their blubber, and boil the blubber on the coast. Whalers would deploy boats from a mothership to kill small groups of whales. They would then establish temporary settlements on the coast to turn the blubber into oil that could be loaded into barrels and returned to the ship. These techniques forced whalers from different nations to rove along the coast of Spitsbergen, which made it likely that they would encounter one another. Initially, the Muscovy Company falsely claimed that English explorers had found Spitsbergen, which meant that it alone had the right to hunt for whales off the island. The Dutch – who had actually discovered the island – insisted that whalers from all European nations should be allowed to fish off its coast. In 1613, a Dutch expedition under Willem van Muyden, the legendary “First Whaleman” of the Republic, reached Spitsbergen in late May and found the coast blocked by ice. After only two weeks, the retreating ice let his whalers enter a bay roughly halfway down the island, but a better-armed English fleet quickly spotted them. In subsequent weeks, the English harassed the Dutch whalers and stole much of their equipment and whale commodities. Yet the Dutch returned with naval escorts in 1614. After the English seized a Dutch ship in 1617, the Dutch arrived with overwhelming force in 1618 and killed several English whalers. The worst skirmishes between Dutch and English whalers raged in years that were relatively warm across the Arctic and probably around Svalbard, despite the generally cooler climate of the early seventeenth century. In cold years, sea ice could have kept whalers working for different companies from lingering on the coast, where tensions simmered and eventually erupted into bloodshed. In any case, the Muscovy Company and the Northern Company eventually agreed to occupy different parts of Spitsbergen. The Dutch would claim the northwestern tip, where they established the major, fortified settlement of Smeerenburg: “blubber town.” The English, meanwhile, took the rest. The Dutch eventually benefited from being closer to the edge of the summer pack ice, where there were more whales to hunt. Hostilities between the English and the Dutch in the volatile first decades of the Svalbard whaling industry convinced the Northern Company to keep a skeleton crew at Smeerenburg and nearby Jan Mayen island during the winter. If they could survive, they would keep Company infrastructure safe from springtime raids and provide valuable information about the region’s winter weather. In 1633/34, two groups of Dutch whalers overwintered at Smeerenburg and Jan Mayen. Regional summer temperatures may have been warming at the time, but winter temperatures across the Arctic were cooling, and 1633/34 was particularly cold. The Smeerenburg group survived the frigid temperatures and killed enough caribou and Arctic foxes to hold off scurvy. The Jan Mayen whalers endured until the spring, but they could not catch enough game to survive the ravages of scurvy. In 1634/35, the Northern Company tried again. This time, both groups died from scurvy, and the Smeerenburg whalers did not even make it to winter. Violent competition between whaling companies – plausibly influenced by warming summers – exposed whalers to a quirk in the climatic trends of the Little Ice Age in the Arctic: the big difference between summer and winter temperatures, relative to long-term averages. Climate change also influenced hostilities between whalers by altering how easily they could reach the “battlefield” around Spitsbergen. In 1615, a year of typical chilliness during the Little Ice Age, the author of a Dutch whaling logbook reported that sea ice on June 7th blocked the crew’s progress towards Svalbard. The crew spotted a bowhead whale three days later, but ice kept them from pursuing. That evening, a storm rose just as they found themselves surrounded by sea ice. They tried to anchor themselves to an iceberg, but it shattered and would have destroyed their ship “had God not saved us.” The few surviving logbooks written by Dutch whalers also record trouble with ice in the warmer 1630s, yet it surely would have been harder to reach Svalbard and compete with English whalers in the first decade of the Arctic whaling industry. Beginning in 1652, the Dutch Republic and England also embarked on hostilities in the North Sea region that would endure, with interruptions, until the Dutch invasion that launched the Glorious Revolution of 1688. During the three Anglo-Dutch Wars that raged in these decades, English and Dutch ordinance kept whalers from sailing to the Arctic or constructing new ships and equipment for the whaling industry. Sailors who might have served aboard whaling ships were urgently needed to crew the warships of the English and Dutch fleets. Many whalers also served as privateers, raiding merchant ships and convoys and then surrendering a share of the profits to their governments. Any whalers who set sail for the Arctic risked losing everything if discovered. As I have written elsewhere, a cooling climate in the second half of the seventeenth century profoundly influenced naval hostilities between the English and Dutch fleets. By altering the frequency of easterly and westerly winds in the North Sea, it helped the English claim victory in the First Anglo-Dutch War but aided the Dutch in the Second and Third Anglo-Dutch Wars, as well as the Glorious Revolution. It probably shortened the First Anglo-Dutch War (1652-54) but lengthened the third war (1672-74). That, in turn, would mean that the manifestations of global climate change in the North Sea affected the opportunities for whalers to engage in hostilities in the Arctic. After 1650, the character of hostilities between Arctic whalers changed dramatically. Cooling summer temperatures brought thick ice into the harbors of Spitsbergen, while the depletion of the bowhead whale population may have worsened the prospects of whaling near land. Whalers had to hunt further and further from the shore, and started processing their whales at sea. They abandoned settlements along the coast of Spitsbergen, which soon fell into ruin. Violence between whalers now took place exclusively at sea. The evidence is spotty, but privateers seem to have hunted whalers in the final decades of the seventeenth century. In 1692, Henry Greenhill, commissioner of the English navy at Plymouth, reported that two “Greenland Prizes” – whaling vessels captured off Spitsbergen – had been brought into harbor. Since England had allied with the Dutch Republic against France, these ships were probably French in origin. The history of climate change, whaling, and violence in and around Svalbard during the seventeenth century is above all complicated, filled with surprising twists and turns. Climate change may have occasionally provoked violence, but it probably did so by reducing, rather than increasing, the accessibility of bowhead whales to whalers. More importantly and more certainly, it altered the character of confrontations between whalers in the far north. Moreover, its manifestations thousands of kilometers from the Arctic ended up having important consequences for hostilities in and around Svalbard. These intricate relationships in the distant past should give us pause as we contemplate the warmer future in the Arctic. Global warming may indeed set the stage for war in the far north, but we have no way of knowing for sure. It is equally likely that climate change will provoke human responses that are hard to guess at present. In this case, we cannot use the past to predict the future, but we can draw on it to ask more insightful questions in the present. ~Dagomar Degroot Selected Works Cited:

Degroot, Dagomar. “Exploring the North in a Changing Climate: The Little Ice Age and the Journals of Henry Hudson, 1607-1611.” Journal of Northern Studies 9:1 (2015): 69-91. Degroot, Dagomar. “Testing the Limits of Climate History: The Quest for a Northeast Passage During the Little Ice Age, 1594-1597.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History XLV:4 (Spring 2015): 459-484. Degroot, Dagomar. “‘Never such weather known in these seas:’ Climatic Fluctuations and the Anglo-Dutch Wars of the Seventeenth Century, 1652–1674.” Environment and History 20.2 (May 2014): 239-273. Hacquebord, Louwrens. De Noordse Compagnie (1614-1642): Opkomst, Bloei en Ondergang. Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 2014. Hacquebord, Louwrens. “The hunting of the Greenland right whale in Svalbard, its interaction with climate and its impact on the marine ecosystem.” Polar Research 18:2 (1999): 375-382. Hacquebord, Louwrens and Jurjen R. Leinenga. “The ecology of Greenland whale in relation to whaling and climate change in 17th and 18th centuries.” Tijdschrift voor Geschiendenis 107 (1994): 415–438. Hacquebord, Louwrens, Frits Steenhuisen and Huib Waterbolk. “English and Dutch Whaling Trade and Whaling Stations in Spitsbergen (Svalbard) before 1660.” International Journal of Maritime History 15:2 (2003): 117-134. Laist, David W. North Atlantic Right Whales: From Hunted Leviathan to Conservation Icon. Washington, DC: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017. McKaya, Nicholas P. and Darrell S. Kaufman. "An extended Arctic proxy temperature database for the past 2,000 years." Scientific Data (2014). doi: 10.1038/sdata.2014.26. |

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed