Species Stories: North Atlantic Right Whales From Their Medieval Past To Their Endangered Present3/21/2018

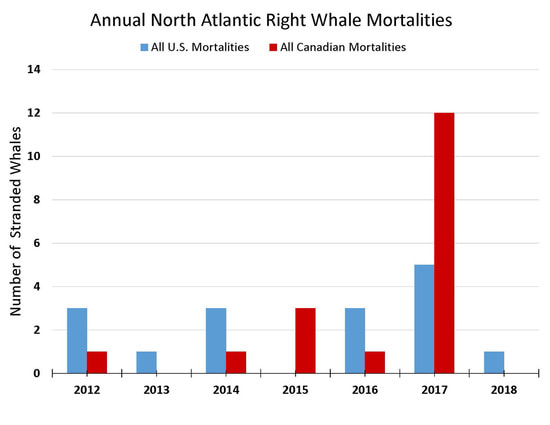

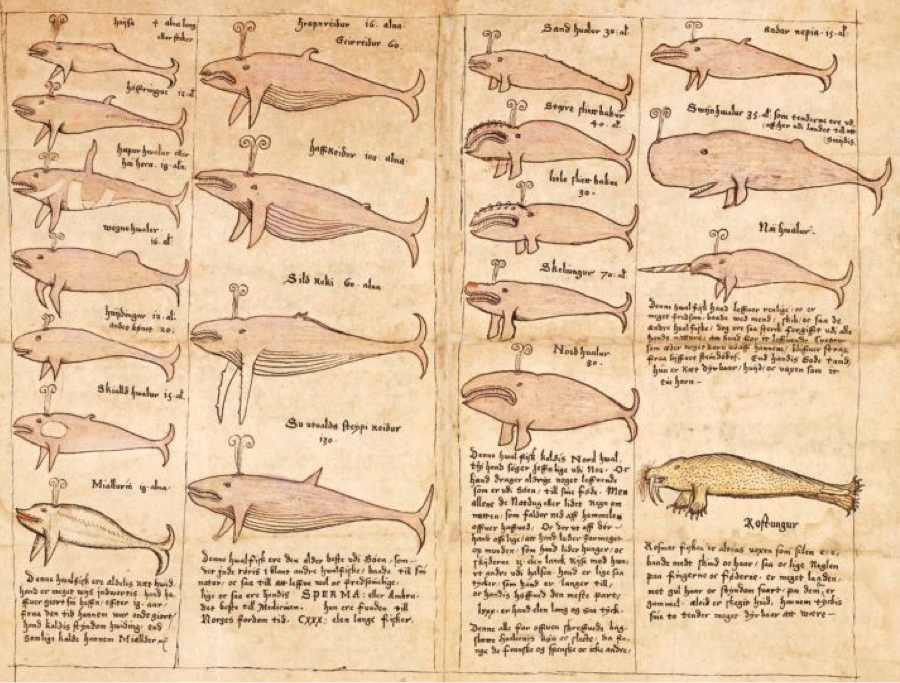

Dr. Vicki Ellen Szabo, Western Carolina University 2017 was a calamitous year for the North Atlantic right whale. The final count of the 2017 "Unusual Mortality Event" or UME, as defined by the Marine Mammal Protection Act, was eighteen animals. Fourteen North Atlantic right whales were found dead from the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to Cape Cod between June and December, with an additional four strandings and entanglements through the year. An average annual mortality rate for the North Atlantic right whale is four animals. To make matters worse, these right whales began 2017 with an estimated population of just 450 animals, including only about one hundred breeding females who have exhibited such stress in recent years that their breeding rate has slowed. As proof of this, in addition to the UME, 2017 saw no recorded calf births. The cause of the UME is no mystery; warming waters have expanded the whales' habitat further north. Bypassing their usual feeding grounds in the Gulf of Maine, most of the whales were found entangled or dead in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where they have sought out their favorite food, Calanus finmarchicus or copepods, a cold water species. Measures in place in more southern waters to prevent entanglements and ship strikes haven't been implemented further north, but as the whales move, so too must these regulations – if there is time left. Marine ecologist Mark Baumgartner of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution ominously noted in December 2017 that North Atlantic right whales, without immediate intervention and protective measures, would be extinct in twenty years. The story of the North Atlantic right whale may end in 2040, but the beginning of the end of this species may have begun a thousand years earlier. North Atlantic right whales, Eubalaena glacialis, earned their common name because of the ease with which they were hunted – they were literally the 'right' whales to hunt. Right whales are bountiful in blubber, giving them exceptional buoyancy, even after death. Their shallow coastal habitat, slow swimming speed, docility, and sizeable pods - averaging twenty but recorded in superpods of one hundred animals - made them accessible and attractive to coastal predation. Averaging fifteen meters in length and 40 - 100 tons in weight, a single right whale could feed and supply a premodern community for months. The deck is stacked, it would seem, against the Atlantic species, and it is clear that all of these natural factors led to significant premodern exploitation of the right whale across the Atlantic. While a population of right whales also exists in the Pacific, predation or natural causes have not led to a dramatic population decline as we see in the Atlantic. Biologists have estimated around 5500 right whales taken across the North Atlantic from the 17th through the early 20th centuries. Reaching an estimated population low of 100 in the 1930s, the species’ brief recovery to approximately 500 animals in the modern era is cold comfort. Without a sense of a historical baseline or 'natural' population of North Atlantic right whales, both in population size and genetic diversity, it is difficult to estimate what a recovered population should look like and whether recovery is even possible. Historians and marine biologists recognize that human exploitation and interference have had a massive impact on the North Atlantic right whale, particularly during and since the sixteenth century. Randall Reeves says that this species has suffered from “one of the most extensive, prolonged, and thorough campaigns of wildlife exploitation in all of human history.” It is a challenge, though, to determine the full extent of human interference in the case of premodern depletions of extinctions. North Atlantic right whales once existed in two presumed separate breeding populations. Still extant, for now, is the population local to the western North Atlantic and the North American coastline. An eastern North Atlantic population, thought to have bred off the coast of the Canaries and migrated along the Atlantic coast to the Subarctic, is presumed extinct. Of this population, though, we know almost nothing with respect to population size, species duration, or genetic diversity. Did changes in premodern climate – the Medieval Climatic Anomaly and the Little Ice Age – affect the whales' migrations and habitats alongside human interference? Were right whales so heavily predated in premodernity that non-industrial whaling could bring about the end of a population? This is the case typically made for North Atlantic gray whales, extinct by the eighteenth century, and for the eastern population of North Atlantic right whales. Does this also explain the precarious state of the western population of North Atlantic right whales? Reeves, in 2007, wrote that “historical research has provided a general perspective on past right whale distribution, population structure, and numbers, but understanding of just how abundant these animals were when whaling began in the North Atlantic remains vague." In 2008, Brenna McLeod led a genetic analysis of historical North Atlantic right whale remains from whaling stations up and down the Labrador coast. McLeod and her team concluded that “the pre-exploitation population size of right whales was clearly much smaller than previously estimated [which] has effected our modern impressions of the recovery of right whale stocks.” In short, predation almost certainly played a role in the species' decline, but the degree remains unclear. The deep history of North Atlantic right whales and their ill-fated engagements with human populations could offer a valuable lens at this critical moment for the species. Historical and archaeological proxy data on cetacean populations, especially for the North Atlantic right whale, may contribute to analysis of modern species populations, habitats, behaviors, and other statistics. Working back from peak points of exploitation through the earliest records of right whale use, historical and archaeological evidence may provide useful context for this imperiled species. We often begin the story of the North Atlantic right whale extirpation with the medieval Basques, who historically have been blamed for the destruction of the eastern branch of the North Atlantic right whale. The Basques established some of the earliest whale fisheries along the European Atlantic coast, maintaining those fisheries from the 13th through the early 20th centuries. Forty-seven medieval and early modern French and Spanish Basque ports have been identified as possible whale fisheries. Alex Aguilar, using catch data from its beginnings in the 16th century, estimates that each port may have taken one or at most two whales a year through the eighteenth century. Far from the depredations wrought by industrial whaling, even this small catch was enough to make an impact on the population, as the Basques were known to target whale calves, and the Bay of Biscay may have been the winter nursery for the eastern population of the North Atlantic right whales. In some ports, Aguilar concluded that the catch of calves accounted for over 20% of records. Additionally, mothers will follow struck calves, making them more readily subject to predation as well, and removing breeding females from the population. This hunting strategy, common among preindustrial whalers, would explain the apparent downturn in catch records by the 18th century and a thinning population that may have precipitated Basque movements to new hunting grounds in North America and the Northeastern Atlantic and Subarctic, where their quarry was the western population of North Atlantic right whales. Also to be considered are possible changing habitats and migrations over the course of the Little Ice Age, when Bowhead whales may have moved south into the Subarctic, potentially competing with right whales for prey. Basque whalers in Labrador reportedly caught well over 20,000 animals, presumed, again, to be right whales. Archaeological and historical investigations of around twenty whaling ports along the Labrador shore, focusing especially on the major Basque port of Red Bay, have forced a reassessment of the role of the Basques in right whale extirpation. In genetic analysis of nearly three hundred whale bones from ten of those ports, only one sample was identified as right whale. Over two hundred bones came from bowhead whales, of which 72 individual animals were identified. The unanticipated number of bowheads on these sites has altered our perceptions not only of the right whale's decline, but also of the expected habitats of the bowhead. While not clearing the Basques of impact in the decline of the right whales, their involvement may not have been central to this population’s decline. The Basques had another crack, potentially, at the North Atlantic right whales during their ill-fated residence in the Icelandic Westfjords, but they weren’t the only hunters targeting these animal populations. Right whales and their utility to human societies has been documented for over a thousand years in Europe. This documentation largely comes from the Northern world, and specifically from Norse populations, from the homeland and across the diaspora. Norse whalers in Ireland, according to a Spanish geographer, spent the 11th century picking off right whale calves, perhaps from the same population travelling through the Bay of Biscay: "… on their coasts, [the Norsemen] hunt the young of the whale, which is an exceeding great fish. They hunt its calves, regarding them as a delicacy. They have mentioned that these calves are born in the month of September, and are hunted in the four months October to January. After this their flesh is hard and no longer good for eating…. Then they cut up the meat of the calf and salt it. Its meat is white like snow, and its skin black as ink." The North Atlantic right whale migration up the European coast peaked in January, but lasted from October through March, according to Aguilar's analysis of the Basque hunt in Spain and southern France. If right whale calves were being taken at multiple points up and down the European coast, the seemingly minimal catch of the Basque ports become magnified in its impact. In addition to the Norse whalers of Ireland, Norsemen back in the homeland itself had already been targeting right whales some three centuries prior. The laconic merchant-hunter Ottar was an Arctic hunter of right whales off the coast of northern Norway, or so he told King Alfred and his court in the ninth century. The whales of Ottar's homeland, he noted, were far bigger than those he fished from the sea off Tromsø, but his ship, along with five others, reportedly killed sixty large whales in the span of two days. Ottar describes the whales as being up to 20 meters long, and while perhaps exaggerated, many historians have surmised that his quarry were right whales, a species called "the first commercial whale." For ninth-century Norsemen, the ability to shoot at and kill whales was second, perhaps, to their capacity to control and acquire. A whale that sank was of no good to anyone, but whales that floated would certainly be keenly sought. Barring any reference to netting, floats, or lines secured by harpoons, a primitive hunter could kill and acquire a right whale if conditions were right. There is good reason to place faith in the ability of hunters like Ottar or the Hiberno-Norsemen to recognize whales they could catch. The twelfth-century anonymous King's Mirror, old Norse Konungs skuggsjá , described the behavior and appearance of over a dozen species of North Atlantic whales. Medieval manuscript illuminations from Scandinavian and Western European texts depict whales in various recognized activities that awe and delight us today - breaching, porpoising, spy-hopping, logging and especially predation. Among the most articulate and observant of all premodern authors was the late medieval Icelander Jón Guðmundsson, also known as Jón Laerði, or Jon the Learned (1574-1658). Jón was a sorcerer and a poet, a physician, outlaw, artist, fisherman, historian, and naturalist. He possessed a wealth of local, traditional environmental knowledge on seafaring, fishing, and especially on whales. Jón was born and lived in the Snaefellsness peninsula in Western Iceland, where he says he saw many whales. He also lived in the Westfjords, where he witnessed and recorded the infamous killing of Basque whalers in 1615. Sometime before his death, perhaps around 1640, Jón wrote a work called the Natural History of Iceland in which he illustrates and describes twenty-two whale species of Iceland. According to Viðar Hreinsson, recent biographer of Jon Laerði, Jón compiled illustrations with Danish captions of nineteen whale species, in addition to a rather skinny walrus, on a loose leaf of paper preserved in the Royal Archive in Copenhagen. The right whale according to Jón exists in two varieties, one smaller, the sléttbakur and a larger animal which he calls höddunefur, measuring 35 ells at the longest (about 17 meters). The smaller whales are the ones most hunted, particularly for their valuable blubber. Icelandic waters, he notes, had been home to a large number of those whales, but the "foreign whalers have reduced the number of this species the most." One wonders which of the right whales – western or eastern North Atlantic - were being preyed upon and whether the diminished species, which he notes, was the beginning of the end of the North Atlantic right whale. In what ways can past histories tell us something new, critical or important about modern animal populations? In the case of the North Atlantic right whale, new technologies like ancient DNA analysis offer a possible means of insight into the current state of this population and context for the references to the species throughout medieval and early modern literature and history. Through an ongoing National Science Foundation Arctic Social Science project, (NSF # 1503714, Assessing the Distribution and Variability of Marine Mammals through Archaeology, Ancient DNA, and History in the North Atlantic; henceforth Norse North Atlantic Marine Mammal Project or NNAMMP) genetic materials from whale remains found on numerous archaeological sites in the North Atlantic and Subarctic may provide evidence related to modern right whale populations. Archaeological sites across the North Atlantic often preserve fragments of marine mammal bones both as artifacts and as butchery or bone working residue. The Norse North Atlantic Marine Mammal Project has compiled over 200 worked and waste whale bone samples from a dozen archaeological sites in Iceland, Greenland, North America, the Faroes and Orkney, ranging from 800 through 1500 CE. Whale bone is a challenging resource for archaeological analysis, defying typical zooarchaeological standards for data recording and analysis. Whale bone is not transported to archaeological sites as part of animal butchery, so bones that are found on a site do not follow regular butchery patterns. Depending on the size of the animal stranded, only 10 to 15% or less of an animal’s body weight may be derived from hard tissues; in the case of North Atlantic right whales, about 13% of an animal’s body weight is bone. This detail becomes important when you consider that the physical evidence of premodern whale use must come from this small percentage of hard tissues, of which only a fraction – if any at all – is transported from a coastal butchering site to an inland settlement. Complicating matters, medieval laws and charters, in Iceland and across the Continent, scrupulously divide stranded whales based on location of stranding, species, class or status of the claimant, and other factors. With all of these metrics in play, recovery of whale bone is not assured on any site, and the bone present on a site may not attest to the quantity of soft tissues used from any animal. Further, to isolate the bones of a single species from massively modified and fragmented whale bone creates an additional challenge for species analysis. Despite these challenges, the Norse North Atlantic Marine Mammal Project and Brenna McLeod at the Frasier lab at St. Mary's University have identified over thirteen unique cetacean species within 200+ bone samples. In those samples, nine unique examples of Eubalaena glacialis have been genetically confirmed across the sampled site assemblages. Over the course of the next year, our project will continue to identify and analyze additional bone samples from across the North Atlantic. Microsatellite analysis of nuclear DNA from identified samples will help to refine which populations of North Atlantic right whales have been found across archaeological sites from North America, Iceland, Greenland, and the Orkney Islands. By 2020, our project will have analyzed over 400 whale bones and we hope to tell a number of species stories, not postscripts, on the whales of the North Atlantic. Selected Works Cited:

Active and Closed Unusual Mortality Events. NOAA Fisheries. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/marine-life-distress/marine-mammal-unusual-mortality-events Aguilar, Alex. “A Review of Old Basque Whaling and its Effect on the Right Whales (Eubalaena glacialis) of the North Atlantic.” Report of the International Whaling Commission, Special Issue 10 (1986): 191-199. Dunlop, D. M. “The British Isles according to Medieval Arabic Authors.” Islamic Quarterly 4 (1957): 11-28. Hreinsson, Viðar. Jón lærði og náttúrur náttúrunnar (Jon the Learned and the Nature of Nature). Reykjavik: Lesstofan Press, 2016. Laist, David W. North Atlantic Right Whales: From Hunted Leviathan to Conservation Icon. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017. Lindquist, Ole. Peasant Fisherman Whaling in the Northeast Atlantic Area, CA 900-1900 AD. Akureyri: Háskólinn á Akureyri, 1997. Lindquist, Ole. “Whaling by Peasant Fishermen in Norway, Orkney, Shetland, the Faeroe Islands, Iceland and Norse Greenland: Medieval and Early Modern Whaling Methods and Inshore Legal Régimes.” In Whaling and History Perspectives on the Evolution of the Industry. Eds. Bjørn L. Basberg, Jan Erik Ringstad, and Einar Wexelsen. Sandefjord: Kommandor Chr. Christensens, 1995, 17-54. McLeod., B., M. Brown, M. Moore, W. Stevens, S. H. Barkham, M. Barkham and B. White. “Bowhead whales, and not right whales, were the primary target of 16th to 17th-century Basque whalers in the Western North Atlantic.” Arctic 61.1 (2008): 61-75. McLeod, B. et al., “DNA profile of a sixteenth century western North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis).” Conservation Genetics (30 Jan. 2009). 10.1007/s10592-009-9811-6. “North Atlantic right whales on the brink of extinction, officials say,” The Guardian, 10 Dec. 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/dec/11/north-atlantic-right-whales-brink-of-extinction-officials-say Palumbi, Stephen R., "Whales, Logbooks, and DNA.” In Shifting Baselines: The Past and the Future of Ocean Fisheries, ed. by Jeremy B. C. Jackson, Karen E. Alexander, and Enric Sala, 163-173. Washington DC: Island Press, 2011. Proulx, J. ‘Basque Whaling Methods, Technology and Organization in the 16th Century.” Trans. A. McGain. In The Underwater Archaeology of Red Bay: Basque Shipbuilding and Whaling in the 16th Century, Volume 1, ed. R. Grenier, M. Bernier and W. Stevens, 42-96. Ottawa: Parks Canada, 2007. Rastogi, T., M.W. Brown, B. A. McLeod, T. R. Frasier, R. Grenier, S. L. Cumbaa, J. Nadarajah and B. N. White 2004. “Genetic analysis of 16th-century whale bones prompts a revision of the impact of Basque whaling on right and bowhead whales in the western North Atlantic.” Canadian Journal of Zoology 82 (2004): 1647-1654. Reeves, R. R., T. Smith and E. Josephson. “Near-annihilation of a species: Right whaling in the North Atlantic.” In S.D.Kraus and R. M. Roland (eds), 39-74. The Urban Whale: North Atlantic right whales at the crossroads. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2007. Roman, Joe and Stephen R. Palumbi. “Whales Before Whaling in the North Atlantic.” Science 301 (25 July 2003): 508-510. Soviet Illegal Whaling in the North Pacific: Reconstructing the True Catches. NOAA Fisheries, 2012. https://www.afsc.noaa.gov/quarterly/ond2012/divrptsNMML2.htm Szabo, Vicki. Monstrous Fishes and the Mead-Dark Sea: Whaling in the Medieval North Atlantic. Leiden: Brill, 2008. Teixeria, R. Venancio, and C. Brito. "Archaeological remains accouting for the presence and exploitation of the North Atlantic right whale Eubalaena glacilis on the Portuguese coast (Peniche, West Iberia), 16th to 17th century." PLOS One 2014 9(2): e 85971 / doi 10.1371/journal.pone.0085971 |

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed