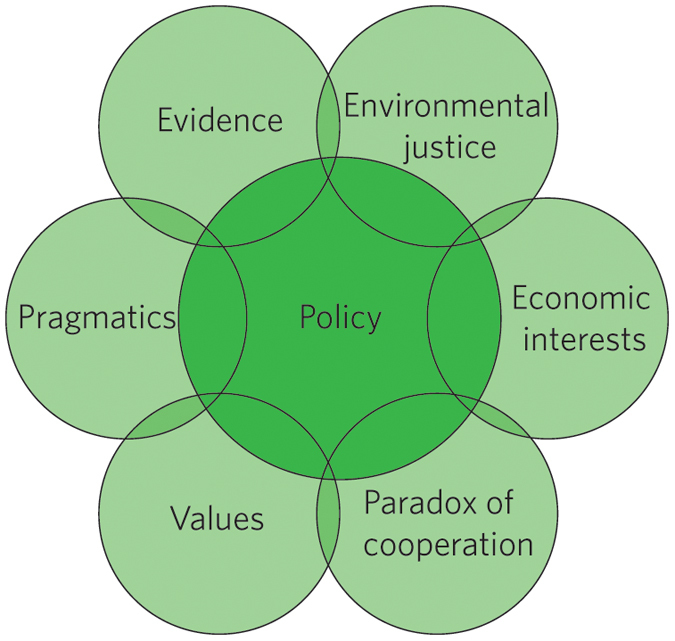

In order to keep global warming below 2° C, there is desperate need for urgency in curbing greenhouse gas emissions. However, national and international policymakers have yet to take action on the scale that would prevent catastrophe. In the most recent issue of Nature Climate Change, Cambridge University geographer David Christian Rose explains why even the governments that have publicly acknowledged the threat of climate change have been so slow to address it. He then introduces practical ways for researchers to communicate more effectively to policymakers. Most scholars understandably assume that policy should respond to the weight of evidence. To them, influencing policy is simply a matter of articulating abundant evidence with clarity. However, Rose argues that evidence derived from “scientific rationality” is just one factor among the many that influence policy. Rose draws on principles developed by political scientist John Kingdon, who holds that even ideas backed by the best scientific evidence do not become policy unless they fit prevailing political conditions. To Rose, nothing is more misguided than the continued focus on producing better evidence, undertaken most famously by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Increasing the certainly of anthropogenic change from 90% (in the IPCC’s fourth report), to 95% (in its fifth), does not account for the ways in which policy is actually formulated.

Rose argues that, in climate change negotiations, progress is rarely impeded by a lack of sufficiently reliable evidence. Instead, Rose claims that talks break down because of questions such as: “Who wins? Who loses? Who decides?” Scientists and other scholars should therefore figure out how their evidence can be presented to policymakers in ways that give it maximum leverage alongside other influences. Scientists and other climate researchers have a tendency to advertise the peril of inaction. Their frequently apocalyptic narratives are both evidence-based, and intended to galvanize policymakers and the public into action. However, Rose finds that telling “good news stories” can be much more effective, because policy is rarely agreed upon without concrete evidence that it will work. By better communicating these stories, academics and activists alike can demonstrate that adaptation is both possible, and applicable in policy. Finally, Rose argues that climate change policy recommendations presented by scientists should be attached to issues that are political winners. As an example, he explains that European researchers campaigning against the trade in wild birds were only able to influence policy when they tied the issue to the spread of bird flu. Given the other political influences faced by policymakers, animal welfare was a political non-starter, but public health was not. Ultimately, the guidelines presented by Rose will strike many academics as cynical recommendations that threaten to turn scientists into lobbyists. Academics, they might claim, should have an unimpeachable voice precisely because they do not employ the tactics used, for example, by big oil lobbyists. Some activists may hold that the inability of political systems to respond directly to evidence is, if left unaltered, a long-term threat to meaningful environmentalism. However, we do not live in a world where these lofty ideals can always yield practical, short-term solutions of the kind necessary to mitigate, and adapt to, global warming. Rose therefore presents a convincing case: if researchers want policymakers to take action, they should start thinking like policymakers. ~Dagomar Degroot David Christian Rose, "Five ways to enhance the impact of climate science." Nature Climate CHange 4 (2014): 522-524. |

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed