|

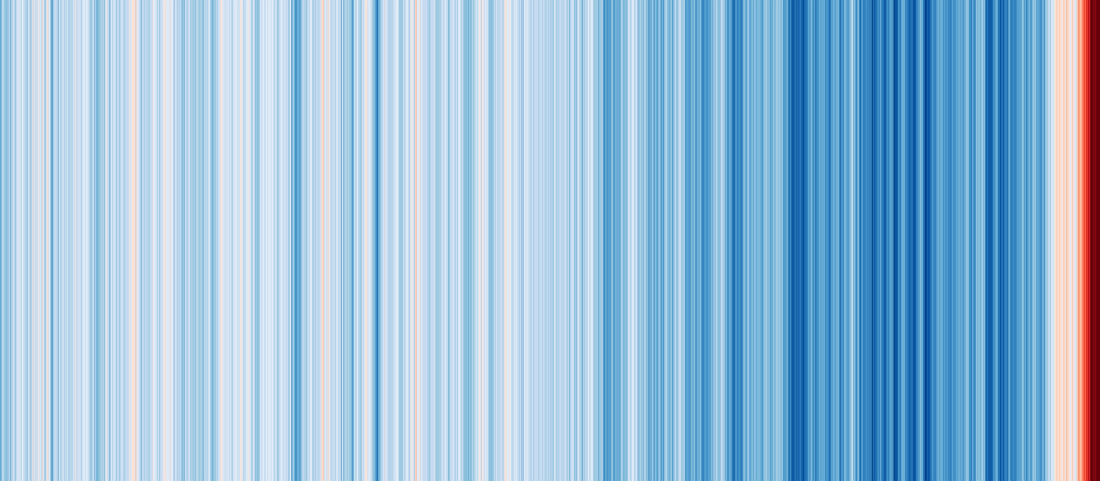

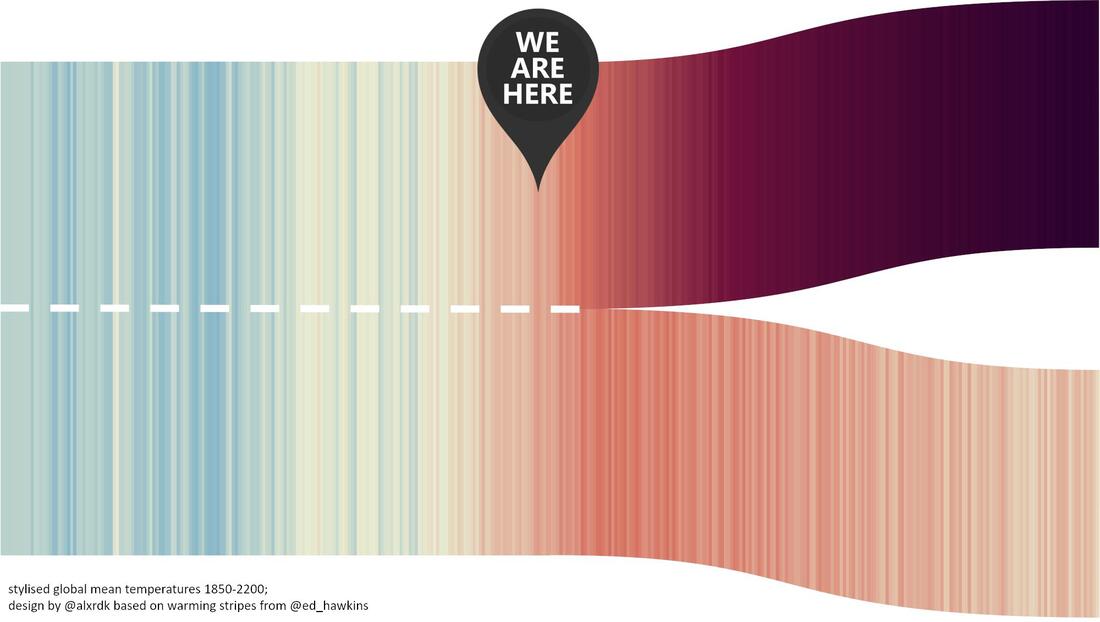

This is the second post in the series Historians Confront the Climate Emergency, hosted by ActiveHistory.ca, NiCHE (Network in Canadian History & Environment), Historical Climatology, and Climate History Network. Dr. Dagomar Degroot, Georgetown University Historians have always concerned themselves as much with the present as the past. Some do so explicitly, their work guided by a conscious desire to provide context for a matter of present concern. Others do so implicitly. They may study the past because it makes them curious, but that curiosity is inevitably shaped by their day-to-day lives. One way or another, history as a discipline is the outcome of the history historians must live through. Today no challenge seems more daunting than the climate crisis. Earth’s average temperature has warmed by over one degree Celsius since the nineteenth century, and it is likely – though not inevitable – that much more warming is on its way. Global temperature changes of this magnitude, with this speed, profoundly alter both the local likelihood and severity of extreme weather. Human-caused heating will reverberate through the Earth for millennia – by slowly melting ice sheets and raising sea levels, for example. Our lives and livelihoods will be – in many cases, are already – shaped by this crisis. No surprise, then, that ever more historians now think urgently and seriously about the implications of climate change for their scholarship. Forecasts of the warmer future are still dominated by economics and climate science, but few now deny that scholars of the past – including historians – can offer unique perspectives on how we entered this crisis, where it might be taking us, and how we can avoid its greatest dangers. As this series reveals, historians grapple with climate change in increasingly diverse ways, and here it is again useful to draw a distinction between implicit and explicit approaches. In a sense, just about every kind of history has relevance to the present crisis, because climate affects every aspect of the human experience. Climate change alters the environments that sustain and shape our lives, shifting the basic conditions that channel our actions and thoughts. The climate crisis is therefore as much about the transformation of the planet as it is about the reshaping of human relationships. Any history that deals with those relationships – all history, by definition – implicitly tells us something about climate change and its social consequences. If you are a historian, your work is about global warming. The editors of this series, however, asked me to describe how scholars of the past explicitly engage with the climate crisis. Arguably, the most influential and numerous publications have originated in both the history of science and the related fields of climate history and historical climatology. A quick and necessarily incomplete overview of just these two kinds of scholarship reveals the value and diversity of historical approaches to climate change. Historians of science initially concentrated on how global warming was discovered and understood by scientists with increasing certainty. While it is simplistic to conclude that scientists “knew” about global warming for many decades, or even over a century – as is often stated in popular media and occasionally in scholarship – historians of science nevertheless revealed the deep roots of today’s scientific understanding of global warming. Led by Naomi Oreskes, they also found that serious debate among climate scientists over the existence of human-caused global warming ended in the 1990s, or perhaps even earlier. Although a majority of the public doesn’t know it, just about every climate scientists understands that humans are today responsible for the rapid heating of the planet. Confirming the scientific consensus on global warming led some historians of science to argue that fossil fuel companies and far-right scientists cynically promoted climate denial in order to serve their regressive political or economic interests. This was – and remains – perhaps the most influential and politically potent argument proposed by historians about the climate crisis. Climate scientists, in this narrative, bravely announced their inconvenient truths but could not overcome the falsehoods propagated by their more media-savvy antagonists. Nevertheless, other historians soon pointed out that climate science has long involved more than the apolitical discovery and communication of truth. Historians of science revealed for example how models and simulations came to dominate climate science – rather than other ways of knowing – and argued that climate scientists themselves failed to choose communications strategies that could mobilize grassroots, local action. Historians have long traced the emergence of ideas about climate from antiquity through the present. Recently, historians of science have revealed that the climate ideas most view as characteristically modern in fact have deep roots. They have shown, for example, that legends of ancient climate changes caused by human sin or shortsightedness helped influence the development of early modern science, and – with new practices in forestry and agriculture – contributed to the emergence of what we might now call sustainability thinking. Climate historians and historical climatologists take an entirely different approach to the climate crisis. Historians active in historical climatology search for human records – usually documents – that either describe past weather or activities that must have been strongly influenced by weather. By finding enough of these records – by scouring what they call the “archives of society” – historical climatologists uncover how climate changed over decades or even centuries. Working with those who uncover evidence for past weather in the “archives of nature” – tree rings, ice cores, or lakebed sediments, for example – they can develop remarkably precise “reconstructions” that reveal the existence of substantial climatic fluctuations even before the onset of today’s extreme warming. The antecedents of this work date back to the nineteenth century, but it was really only in the 1970s that Christian Pfister and other pioneers proposed ranking qualitative accounts of weather on simple ordinal scales. These scales allowed for the closer integration of the archives of society with the archives of nature, especially in Europe, but historical climatologists studying different parts of the world continued to use distinct methods for quantifying historical evidence. Only now are they working towards developing a common approach. In any case, reconstructions permit histories of human responses to past climate changes. While these climate changes have been relatively modest in global scale – the Little Ice Age, the most studied period of preindustrial climate change, only cooled the Earth by several tenths of a degree Celsius between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries – some were nevertheless sufficient to dramatically alter local environments. Archaeologists, economists, geneticists, geographers, linguists, literary scholars, and paleoscientists have all used distinct methods and sources to uncover how these alterations shaped the history of human populations. Yet few disciplines have contributed more to this scholarship – recently coined the “History of Climate and Society” – than history. Historians have in recent years increasingly avoided making simple connections between climate changes, harvest failures, and demographic disasters: a chain of events that scholars of past climate have long emphasized. New climate histories instead uncover wellsprings of both vulnerability and resilience within communities, and they increasingly consider the full range of possible relationships between climate change and human history across the entire world and into the twentieth century. Together, historians of science and climate historians have done much more than add a little climate to historians’ understanding of the past. Histories of climate science help uncover why governments and corporations have not responded quickly or adequately to the climate crisis. They also reveal how the crisis might be communicated more effectively, or how more diverse ways of knowing could be incorporated within climate science. They show us why we should nevertheless believe the forecasts of climate science – and how we can best act on that belief. Historical climatology helps reveal the baselines against which human emissions are changing Earth’s climate today, and helps uncover the likely response of local environments to global warming. Climate historians can suggest what strategies may succeed or fail when climates change, and add complexity to forecasts of the future that too often assume simple social responses to shifting environmental conditions. Many tell stories about the influence of climate on human affairs that capture public attention more vividly than frightening statistics ever could. Yet both climate history and historical climatology also demonstrate the fundamental discontinuity between climates present and past. The speed, magnitude, and cause of present-day warming simply has no parallel in the history of human civilization. History is a guide to climate action, but it also warns us that to a large extent we are in uncharted waters. Ten years ago, when I started this website, my message was something like: believe me, history helps us understand global warming! I could not have imagined that, in just ten years, climate change would be widely recognized as a serious subject for historical study – or that historians such as Ruth Morgan would earn a seat in a working group of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In some ways, the sea change in the historical discipline has mirrored a broader transformation in social attitudes towards climate change: a transformation driven in part by the courage of young activists, but also by the growing severity of the climate crisis. Climate scholarship in history is now more numerous and more diverse – in its topics and authorship – than it ever has been, a shift that also echoes developments in climate activism.

I expect these trends to continue. When future historians write about our time, you can be sure that climate change will play a central role in the story. As we live through that history, our scholarship will be climate scholarship – whether we see it that way or not.

0 Comments

Ecological Militarism: The Unusual History of the Military’s Relationship with Climate Change5/25/2018

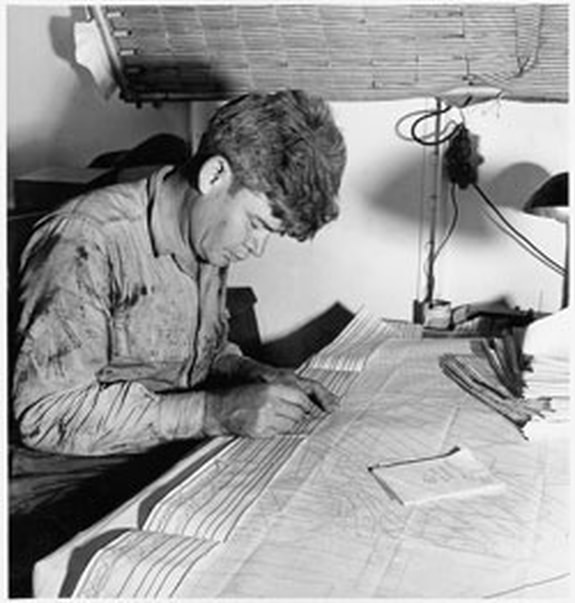

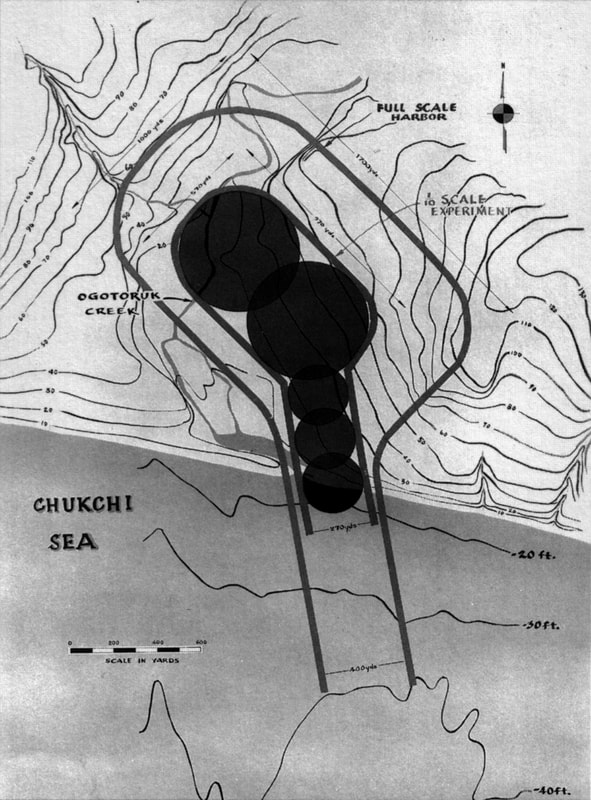

Adeene Denton, Brown University Many historians have discussed the influence of the Cold War on the development of specific disciplines within the broader field of earth science. However, few have touched on U.S. military’s study of and attempt to capitalize on climate change, an interest that accelerated rapidly during the Cold War. The decades-long studies sponsored by the Departments of Defense and Energy during and after the Cold War produced a wide array of attempts to transform the earth itself into a political and environmental weapon. The concept of anthropogenic climate change (also known as global warming) captured the world’s attention when James Hansen and other scientists testified before Congress in a series of hearings between 1986 and 1988. However, it had for decades been a subject of debate in smaller scientific, political, and corporate communities. Throughout the Cold War, American political and military leaders considered the potential of specifically directed, human-engineered climate change. They believed that cloud seeding and the atomic bomb, among other tools, would allow them to wield the geological force necessary to control Earth’s climate. Anthropogenic climate change was therefore a concept that excited many U.S. military planners during the early Cold War. Yet these planners, and the scientists and politicians who supported their efforts, struggled with the colossal scale of their desires. They yearned to use human technology to shape the Earth to their political will, but found themselves stymied by the very technologies and politics they sought to control. When the Earth Became Global For a science that is built on the concept of change over inconceivably long timescales, earth science developed at a breakneck pace during the Cold War. As earth science grew both in numbers of people working under its banner and the amount of data they had at their disposal, the field subdivided rapidly (in a case of science imitating life). The 1950s saw a fascinating dual development within earth science: scientists were increasingly recruited to work with and for their national militaries, even as they developed datasets and connections with other scientists that were global in nature. Scientists who wanted to study the history of the earth were looking for datasets that spanned the world, not just their country’s borders. They could only compile them through extensive collaboration with other nations, on the one hand, or, on the other, the vast quantities of funding and manpower that only a major military could offer. Oceanographers chose the latter option as their best chance for technological exploration of the oceans. U.S. naval vessels became the hosts of scientific research cruises, as they had the greatest mobility and most advanced technology of any ships in the world. Many scientists collecting these data were loath to discuss the tensions between their research and any political agendas, but it was certainly on their minds – and on the minds of their benefactors. For the Navy and the other branches of the U.S. military, scientific projects typically served multiple purposes. The data collected provided both a research boost to a specific scientific community, and information that the military might be able to use. Radio arrays in the Caribbean, for example, which were ostensibly used for ocean floor sounding and bathymetric mapping, also scoured the sea for Soviet submarines. Overall, the military hoarded big data about the earth and its climate for use in future tactical and strategic plans. Climate and environmental science became yet another venue in which the Cold War was fought. Yet the relationship between climate science and the political interests that funded it was an uneasy one. When researchers in conversation with the military realized that humanity was becoming a force that could act on a geologic scale, the possibility of extending U.S. control to the environment became extremely appealing to military planners. As American oceanic scientists saw the bathymetry of the seafloor for the first time, the political and military forces in Washington were haggling over just how much ocean the U.S. could control outside its borders. American oil companies like Chevron and Mobil became technological giants over the course of the Cold War by expanding their search for petroleum to South America and Africa, and their profits seemed to suggest that the earth’s interior was also within the scope of human knowledge and jurisdiction. After 1957, the dawn of the space age seemed to herald the beginning of total surveillance from above, and for the military planetary surveillance was the beginning of integrated planetary control. The more scientists discovered about the earth on which they lived, the more their military partners sought to use that information to bring the earth to heel. All of these ideas seemed to coalesce together during the Cold War, yielding decades of oscillating cooperation and struggle between the U.S. military and the scientists it patronized. The Military as a Geological Force During the early Cold War, U.S. military planners often proposed schemes to transform environments on immense scales, only to quickly abandon them either in the proposal stage or after initial testing. The initial popularity of such ideas, as well as their typically quick demise, owed much to military ambitions far exceeding capability. Environmental control was an undeniably powerful concept, as it promised ways to turn the tides of war through untraceable methods, or from continents away. Unfortunately, the military’s tactical plans to utilize newfound climate information often took unusual (and unusable) turns because much of the information was very new, and because experts consulted were not always well versed in the information they handled. Climate science was a field in its infancy, and not everyone who claimed to speak on its behalf understood the data. A classic example of this phenomenon was proposal developed by Hungarian-American polymath John von Neumann to spread colorants on the ice sheets of Greenland and the Antarctic. By darkening the ice, the military could reduce their reflectivity, or albedo, which would warm the poles, melt the ice, and ultimately flood the coastlines of hostile nations. It was an absurd idea proposed by a brilliant physicist who did not yet grasp how global the effects of such a plan would be. Melting of the Greenland ice sheet in particular would have drastic impacts on the North American continent as well as the intended target. The U.S. Departments of Energy and Defense, as well as President Eisenhower, were also interested in using humanity’s newfound power for good, however. Operation Plowshare, for example, was the name given to a decades-long series of attempts to use nuclear explosives for peaceful purposes, particularly construction. It resulted in of proposals such as Project Chariot in 1958, which called for the use of five thermonuclear devices to construct a new harbor on the North Slope of Alaska. Scientists were often split in their reactions to these proposals, a conflict provoked by their valuable relationship with the U.S. government, on the one hand, and risk to terrestrial environments they were only beginning to understand, on the other. Mud, Not Missiles: Weaponizing Weather in Vietnam When the U.S. military started seriously considering the possibility of human-driven climate warfare, its planners focused on a concept that has been human minds for centuries: controlling the weather. Weather modification has preoccupied scientists, politicians, and the military in the U.S. since James Espy, the first “national meteorologist” employed by the military, studied artificially-produced rain in the 1840s. In the early Cold War, such projects continued to intrigue military planners. In 1962, the U.S. military launched Project Stormfury, an attempt by researchers at the Naval Ordinance Test Station (NOTS) to test weather control by seeding the clouds of tropical cyclones. They hoped to weakened hurricanes that regularly wreaked havoc on the southern and eastern coasts of the United States. They theorized that the addition of silver iodide to hurricane clouds would disrupt the inner structure of the hurricanes by freezing supercooled water inside. Yet their cloud seeding flights revealed that the amount of precipitation in hurricanes did not appear to correlate at all with whether a cloud had been seeded or not. In the meantime, however, members of the U.S. high command used the theory behind Stormfury as a basis for two similar operations in Asia: Projects Popeye and Gromet. Despite Project Stormfury’s failure to deliver measurable results, the need for any kind of interference that could harry the Viet Cong led military planners to rush Popeye into the testing phase. The scientists recruited to assist with Popeye slightly modified Stormfury’s cloud seeding approach. They decided to use lead iodide and silver iodide in large, high-altitude, cold clouds, which (in theory) would then “blow up” and “drop large amounts of rain” over an approximately targeted area. If successful, Popeye would increase the rainfall during the monsoon season over northern Vietnam, hampering their forces by destroying their supply lines. This would lengthen the monsoon season, which would force the Vietcong to deal with landslides, washed out roads, and destroyed river crossings. American officials had also promised the Indian government that they could seed clouds to end a crippling drought in India. Cloud seeding, military planners, could both win allies and cripple enemies. Despite the eagerness and ambition with which the U.S. military undertook testing of this method in both India (with government permission) and Laos (without informing the Laotian government), it was ultimately unclear whether these attempts at “rainmaking” were effective at all. The utmost secrecy with which Projects Gromet (in India) and Popeye (in Laos and Vietnam) were undertaken limited attempts to measure and verify their success. Gromet alone cost a minimum of $300,000 (nearly $2 million in present-day US dollars), yet by 1972 U.S. officials had to concede that its effectiveness had been unclear at best. The Indian drought ended, but no one could say whether it was the U.S. that had done the job. Politics, Military, and Oceans For scientists, the ocean represents a crucial biological and chemical reservoir whose massive size makes any fluctuation of oceanic conditions a crucial aspect of climate change. In the early Cold War, the oceans also became a focus for the development of poorly conceived climate control plans, as well as a site for political posturing. There were two basic prongs to the American (as well as other countries’) political and military approach to the oceans during the Cold War. First, the oceans were seen as a way to extend a country’s sovereign borders, and second, as a mechanism for disposing of unsavory nuclear waste. As American scientists followed the Navy to exceedingly remote places in search of new datasets, the question of nationalism followed them. Where could the Navy “plant the flag” as part of its surveys? Polar scientists who sought direct access to their regions of interest – the Arctic and Antarctic – were hamstrung by the security interests of not just their own nations, but also of others. The U.S. government, which noted the conveniently large strip of polar access given by USSR’s ~7,000 km of Arctic coastline, pushed to extend its sovereignty as far off of Alaska’s northern continental shelf as it could. Where scientists saw the Arctic as a fascinating environment and ecosystem, the U.S. military saw a direct route to its biggest enemy. In Antarctica, meanwhile, by the International Geophysical Year (1957-1958) over seven different countries had laid claim to large swaths of the frozen continent. The British had already secretly built a base on Antarctic Peninsula during World War II to supersede other claims to the area. Establishing the Antarctic continent as a zone that was to be as free from geopolitics as possible (as well as exploitative capitalist interests) was a difficult task, and one that took decades. It took until the Clinton administration for oil companies to be officially banned from prospecting on or near the continent, essentially reserving Antarctica as a place where only collaborative science could reign. As the U.S. and other major powers jockeyed with each other for territory in the most remote areas of the world, they also used the ocean as a garbage disposal for some of humanity’s most toxic waste. Between 1946 and 1962, the United States dumped some 86,000 containers of radioactive waste into the oceans, while Britain, the USSR, and other developing nuclear powers did much the same. Meanwhile, scientists from the International Scientific Committee on Ocean Research started collecting data on the possible dangers associated with radioactive waste. However, governments funding their research had little interest in the results until U.S. waste washed back up onto American shores where local fishermen found and identified it. For years, the ocean was convenient to U.S. officials. Its volume seemed limitless: perfect for permanently keeping radioactive waste, and any information about it, from the public eye. Fortunately, oceanic waste dumping did not stay a secret forever. There was, it seemed, no convenient way to dispose of radioactive waste. Dumping it on land provoked public criticism at home, and dumping it in the oceans invited international criticism, particularly from the Soviet Union, whose government claimed to have never done such a thing. In fact, it did; the USSR sank eighteen nuclear reactors in addition to packaged waste, a fact only revealed in declassified archives after the Soviet Union collapsed. To describe the relationship between the U.S. government and the oceans during the Cold War as fraught would be an understatement. The Navy wanted the ocean to be an effective source of information on Soviet activities, a convenient landfill, and a platform to extend American political authority. In the end, the Navy could not have it all. By the end of the Cold War, the Navy and its political supporters had to concede to public and scientific pressure to back away from large-scale projects that overtly exploited the ocean. The power jockeying and technological exploitation during the Cold War did have lasting effects, however. Today, the oceans remain a site of intense monitoring and political grandstanding. The Cold War and the Warm Future In his speech to the National Academy of Sciences in 1963, President Kennedy noted that human science could now “irrevocably alter our physical and biological environment on a global scale.” This was a fundamental realization – that humans could change the world, and they could do it in a matter of minutes to years if they chose. The Cold War forced scientists and their military benefactors to realize that humans had become more efficient at shaping the Earth than most geological forces in existence. It was tempting, then, for Cold War militaries to investigate just how far that power could go, in both destructive and constructive ways. Can we lengthen or shorten the seasons? The military tried it. Can we disappear our worst waste in the oceans? Every country with nuclear waste tried it. How much do we need to know about the environment before we can begin to reshape whole regions to suit nationalistic goals and objectives? For the military during the Cold War, the answer was almost always “we know enough.” For some of the scientists they employed, and many more whom they didn’t, the answer was “we may never know enough.” Popular discussions rarely touch on the outlandish attempts to control nature during the early Cold War. In our present age of polarization around the issue of climate change, perhaps they should. Politicians and scientists too often assume that humanity will someday engineer a solution to climate change, but the Cold War’s history reveals that our grandest schemes may be the most susceptible to failure. Selected References Doel, R.E. and K.C. Harper (2006). “Prometheus Unleashed: Science as a Diplomatic Weapon in the Lyndon B. Johnson Administration.” Osiris 21, 66-85.

Fleming, J.R. Fixing the Sky: The Checkered History of Weather and Climate Control. Columbia University Press: New York City. 2010. Hamblin, J.D. (2002). “Environmental Diplomacy in the Cold War: The Disposal of Radioactive Waste at Sea during the 1960s.” The International History Review 24 (2), 348-375. Marzec, R.P. Militarizing the Environment: Climate Change and the Security State. University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis. 2015. Naylor, S., Siegert, M., Dean, K., and S. Turchetti (2008). “Science, geopolitics and the governance of Antarctica.” Nature Geoscience 1. O’Neill, Dan (1989). “Project Chariot: How Alaska escaped nuclear excavation.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 45 (10). “Text of Kennedy’s Address to Academy of Sciences,” New York Times, Oct 23, 1963, 24. |

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed