|

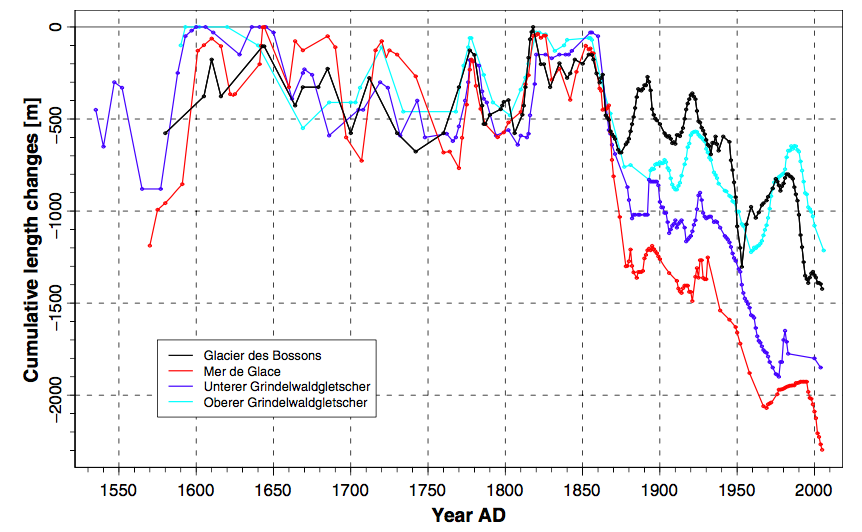

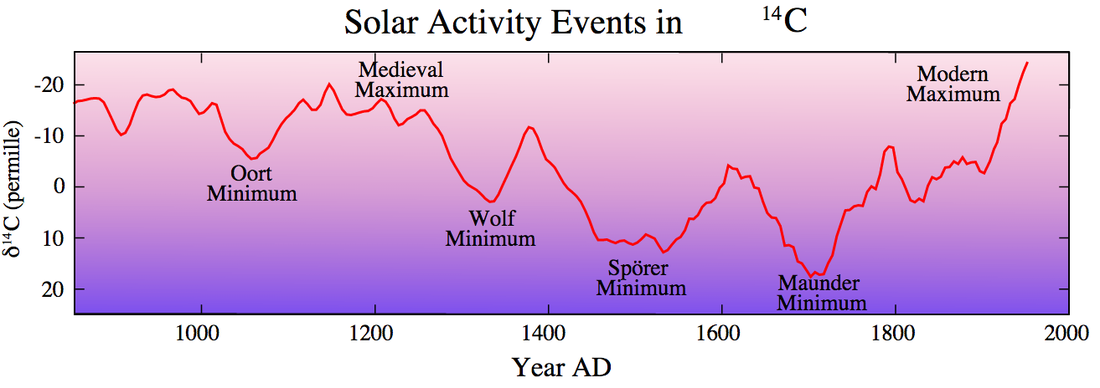

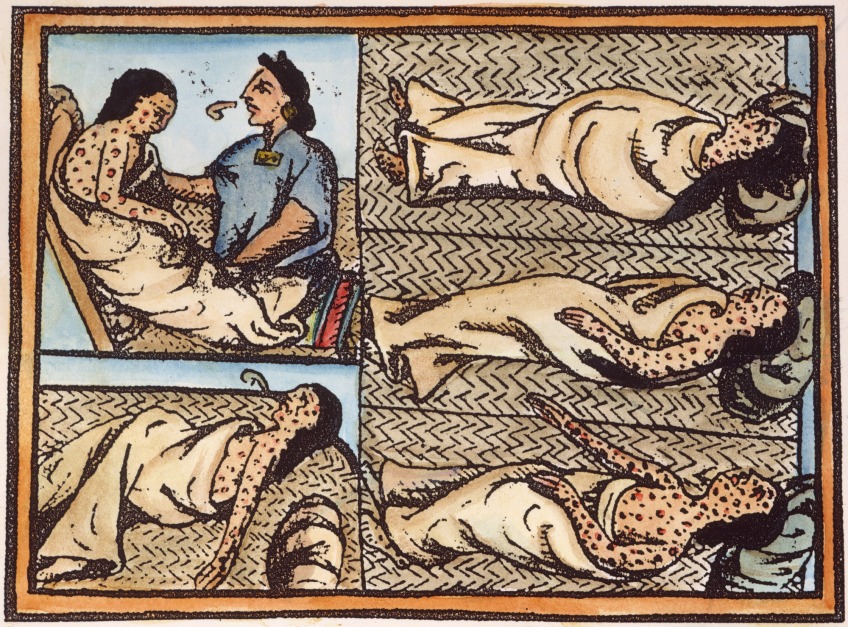

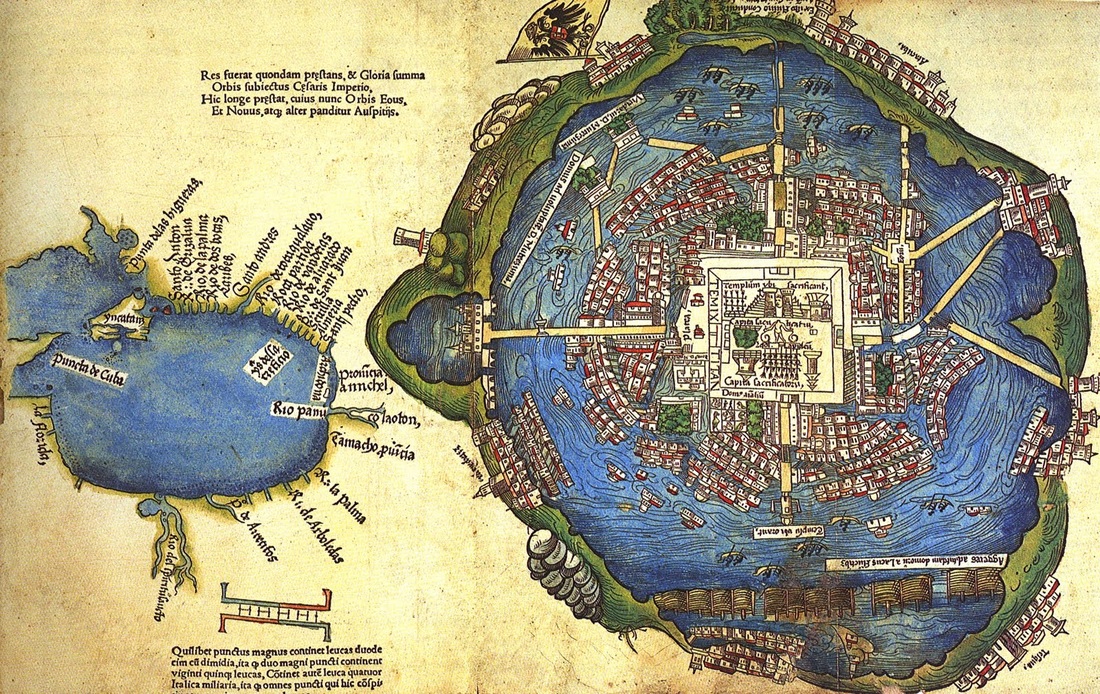

Ask most people about climate change, and you will soon find that even the relatively informed make two big assumptions. First: the world’s climate was more or less stable until recently, and second: human actions started changing our climate with the advent of industrialization. If you have spent any time reading through this website, you will know that the first assumption is false. For millions of years, changes in Earth’s climate, driven by natural forces, have radically transformed the conditions for life on Earth. Admittedly, the most recent geological epoch – the Holocene – is defined, in part, by its relatively stable climate. Nevertheless, regional and even global climates have still changed quickly, and often dramatically, in ways that influenced societies long before the recent onset of global warming. Take, for example, the sixteenth century. Relative to early twentieth-century averages, the decades between 1530 and 1560 were relatively mild in much of the northern hemisphere. Yet, after 1565, average annual temperatures in the northern hemisphere fell to at least one degree Celsius below their early twentieth-century norms. Despite substantial interannual variations, temperatures remained generally cool until the aftermath of a bitterly cold “year without summer,” in 1628. Since the expansion of the glacier near Grindelwald, a Swiss town, was among the clearest signs of a chillier climate, these decades are collectively called the “Grindelwald Fluctuation.” It was one of the coldest periods in a generally cool climatic regime that is today known as the “Little Ice Age.” Volcanic eruptions undoubtedly caused some of the cooling. In 1595, the eruption of Nevado del Ruiz released sulphur aerosols into the atmosphere, scattering sunlight and thereby cooling the planet. Just five years later, Huaynaputina exploded in one of the most powerful volcanic explosions of the past 2,500 years. Major volcanic eruptions following in close proximity to one another can trigger long-term cooling by activating "positive feedbacks" in different parts of Earth’s climate system. In the Arctic, for example, volcanic dust veils lead to chillier temperatures, which can increase the extent of Arctic ice that, through its high albedo, reflects more sunlight into space than the water or land it replaces. That in turn leads to even cooler temperatures, more ice, and so on. However, the onset of the Grindelwald Fluctuation preceded the eruption of Nevado del Ruiz by some thirty years. Clearly, volcanoes were not the only culprits for the colder climate. Some scientists believe that low solar activity also played a role. Yet, although the sun was less active during the Grindelwald Fluctuation than it is today, it will still more active than it was in most other decades of the Little Ice Age. That leads us to our second assumption: the idea that anthropogenic climate change began with industrialization. Most scholars of past climate change would still agree, but that might be changing. Recently, a growing body of evidence has started to suggest that humanity’s impact on Earth’s climate might be much older. Human depravity, it seems, might have been to blame for the cooling of the sixteenth century. Back in 2003, palaeoclimatologist William Ruddiman proposed that humans were to blame for preindustrial climate change, in a groundbreaking article that shocked the scientific community. Two years later, he thoroughly explained and defended his conclusions in book called Plows, Plagues, and Petroleum: How Humans Took Control of Climate. Ruddiman argued that humanity had slowly but progressively altered Earth’s atmosphere since the widespread adoption of agriculture. Some 8,000 years ago, communities in China, Europe, and India made room for agricultural monocultures by burning away forests. According to Ruddiman, the scale of deforestation was enough to steadily increase the concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Then, from around 5,000 years ago, rice farming and, to a lesser extent, livestock cultivation slowly raised atmospheric methane concentrations. Ruddiman concluded that the cumulative effect of these anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions was to gradually increase average global temperatures, and perhaps ward off another ice age. Ruddiman also argued that, since the adoption of agriculture, temporary fluctuations in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations followed from dramatic changes in human populations. During major disease outbreaks, Ruddiman insisted, populations declined to such an extent that agricultural land went untilled on a vast scale. Woodlands expanded, pulling more carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere than the agricultural crops they replaced, and thereby cooling the planet. When populations recovered, farmers burned down forests and planted their monocultures, warming the Earth. During the sixteenth century, Spanish soldiers and settlers established a vast empire by waging environmentally destructive wars on the indigenous peoples of central and southern America. They forced many of the survivors into new settlement patterns and gruelling forced labour. They also disrupted indigenous ways of life by appropriating, and often transforming, regional environments. Their animals, plants, and pathogens encountered virgin populations and spread rapidly. Indigenous communities in hot, humid climates were especially vulnerable to outbreaks of Eurasian crowd diseases, which included smallpox, measles, influenza, mumps, diphtheria, typhus, and pulmonary plague. Recent population modelling suggests that the population of the Americas declined from approximately 61 million in 1492 to six million in 1650. By the late sixteenth century, this holocaust was well underway. Land previously colonized by indigenous communities through controlled burning or the planting of agricultural monocultures gradually reverted to woodlands. While all plants inhale carbon dioxide and exhale oxygen, tropical rainforests are much more effective carbon sinks than human crops. In the Americas, reforestation on a vast scale probably lowered atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide by 7 to 10 parts per million between 1570 and 1620. Human cruelty may therefore have contributed to the climatic cooling also caused by volcanic eruptions and, maybe, a decline in solar radiation relative to modern or medieval norms. A growing body of scholarship now provides evidence for these relationships. However, there are many questions that must be answered before we can confidently conclude that depopulation helped trigger the Grindelwald Fluctuation, let alone other episodes of climatic cooling. For instance: did the cooling effect of sixteenth-century reforestation in the Americas overwhelm the warming influence of contemporaneous deforestation in China and India? Were invasive species introduced by Europeans into the Americas incapable of preventing reforestation? Was the pace of depopulation, and in turn reforestation, really so fast and so universal that it could substantially reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations over the course of a few decades? It will take a while to answer these questions, but some scholars are already drawing big conclusions. Earlier this year, geographers Simon Lewis and Mark Maslin argued that the cooling set in motion by the depopulation of the Americas could be considered the beginning of the “Anthropocene,” the proposed geological epoch dominated by human transformations of the world’s environment. Dating big changes in geological time is tricky business. The changes must be visible in the global stratigraphic record – that is, in rock layers – and they must be traceable to a specific date. Lewis and Maslin lean on earlier environmental histories of the “Columbian Exchange,” the European transfer of plants, animals, and pathogens between the New and Old Worlds. The impact was a global biotic homogenization that, according to Lewis and Maslin, should be visible in the stratigraphic record. That still leaves them without a specific date, however. They settle on 1610, because that was when atmospheric carbon dioxide levels reached a minimum caused, they say, by European depopulation of the Americas. There may be one more wrinkle to this sad story. In a forthcoming book, I argue that the Dutch revolt against the Spanish empire was provoked, in part, by high food prices that followed from harvest failures during the chilly onset of the Grindelwald Fluctuation. Then, until the early seventeenth century, the Dutch rebellion benefitted from a chilly climate. Dutch fortifications routinely forced Spanish armies to stay in the field during the frigid winters of the Grindelwald Fluctuation. The effect on Spanish soldiers could be disastrous. It is possible, therefore, that Spanish conquests in one part of the world contributed to climate changes that benefitted a rebellion against Spanish rule in another.

If so, the Eighty Years’ War may provide one of the first examples of such a self-defeating climate history of violence. It was certainly not the last. Recently, interdisciplinary researchers have found similar connections at work in the Syrian civil war. In a poorly governed society already destabilized by migrants fleeing the American invasion of Iraq, a severe drought caused, in part, by anthropogenic warming created fertile conditions for rebellion. The countries now at war in Syria and Iraq include those most responsible for the climate change that helped set the conflict in motion. Studying the Grindelwald Fluctuation may provide deep context for these relationships, by rooting them in a long history of violence and environmental transformation. It may also show that both assumptions commonly held about climate change are wrong. ~Dagomar Degroot My thanks to professors John McNeill, Richard Hoffmann, and Sam White for suggesting sources and helping me think through these relationships. Graph Source: Nussbaumer, Samuel U. and Heinz J. Zumbühl, "The Little Ice Age history of the Glacier des Bossons (Mont Blanc massif, France): a new high-resolution glacier length curve based on historical documents." Climatic Change 111 (2012): 301-334. On Volcanic Cooling: Sigl, Michael, M. Winstrup, J. R. McConnell, K. C. Welten, G. Plunkett, F. Ludlow, U. Büntgen, M. Caffee, et al., “Timing and Climate Forcing of Volcanic Eruptions for the Past 2,500 Years,” Nature 523 (2015): 543–49. On Anthropogenic Cooling: Dull, Robert A., Richard J. Nevle, William I. Woods, Dennis K. Bird, Shiri Avnery, and William M. Denevan. “The Columbian Encounter and the Little Ice Age: Abrupt Land Use Change, Fire, and Greenhouse Forcing.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 100 (2010): 755–71. doi:10.1080/00045608.2010.502432. Etheridge, D. M., L. P. Steele, R. L. Langenfelds, R. J. Francey, J.-M. Barnola, and V. I. Morgan. “Natural and Anthropogenic Changes in Atmospheric CO2 over the Last 1000 Years from Air in Antarctic Ice and Firn.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 101, no. D2 (1996): 4115–28. doi:10.1029/95JD03410. Ganopolski, A., R. Winkelmann, and H. J. Schellnhuber. “Critical insolation–CO2 Relation for Diagnosing Past and Future Glacial Inception.” Nature529 (2016): 200–203. doi:10.1038/nature16494. Hunter, Richard, and Andrew Sluyter. “Sixteenth-Century Soil Carbon Sequestration Rates Based on Mexican Land-Grant Documents.” Holocene 25 (2015): 880–85. doi:10.1177/0959683615569323. Kaplan, Jed O. “Holocene Carbon Cycle: Climate or Humans?” Nature Geoscience 8 (2015): 335–36. doi:10.1038/ngeo2432. Lewis, Simon L. and Mark A. Maslin. “Defining the Anthropocene.” Nature 519 (2015): 171-180. Mitchell, Logan, Ed Brook, James E. Lee, Christo Buizert, and Todd Sowers. “Constraints on the Late Holocene Anthropogenic Contribution to the Atmospheric Methane Budget.” Science 342 (2013): 964–66. doi:10.1126/science.1238920. Nevle, R.J., D.K. Bird, W.F. Ruddiman, and R.A. Dull. “Neotropical Human–Landscape Interactions, Fire, and Atmospheric CO2 during European Conquest.” The Holocene 21 (2011): 853–64. doi:10.1177/0959683611404578. Pasteris, Daniel, Joseph R. McConnell, Ross Edwards, Elizabeth Isaksson, and Mary R. Albert. “Acidity Decline in Antarctic Ice Cores during the Little Ice Age Linked to Changes in Atmospheric Nitrate and Sea Salt Concentrations.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 119 (2014): 5640–52. doi:10.1002/2013JD020377. Ruddiman, William. “The Anthropogenic Greenhouse Era Began Thousands of Years Ago.” Climatic Change 61 (2003): 261–93. Ruddiman, William. Plows, Plagues, and Petroleum: How Humans Took Control of Climate. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005. Ruddiman, William, Steve Vavrus, John Kutzbach, and Feng He. “Does Pre-Industrial Warming Double the Anthropogenic Total?” The Anthropocene Review 1 (2014): 147–53. doi:10.1177/2053019614529263. Wang, Z., J. Chappellaz, K. Park, and J.E. Mark. “Large Variations in Southern Hemisphere Biomass Burning During the Last 650 Years.” Science330 (2010): 1663–66.

Dan Pangburn

2/29/2016 04:18:25 pm

Perhaps some scientists are using the wrong approach. Perhaps the many people trying to solve the problem have the wrong skill set. A mechanical engineer’s approach has identified the two main climate change drivers and even quantified the tiny effect of CO2, all with better than 97% match to reported average global temperatures since before 1900. The analysis is at http://globalclimatedrivers.blogspot.com

David Zylberberg

3/1/2016 10:01:46 am

Dr. Degroot, 3/5/2016 03:10:53 am

Hi David,

Javier

6/19/2016 11:01:12 am

A quite unscientific proposition.

Dagomar Degroot

6/19/2016 11:53:49 am

Javier,

Roberto Ferrero

1/4/2018 11:17:46 am

Maybe it was the other way round. 10/5/2019 03:19:33 am

I look forward to hearing more updates from you, this helps me a lot.

The tabernacle was distributed nationwide, especially in Jiangxi. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed