|

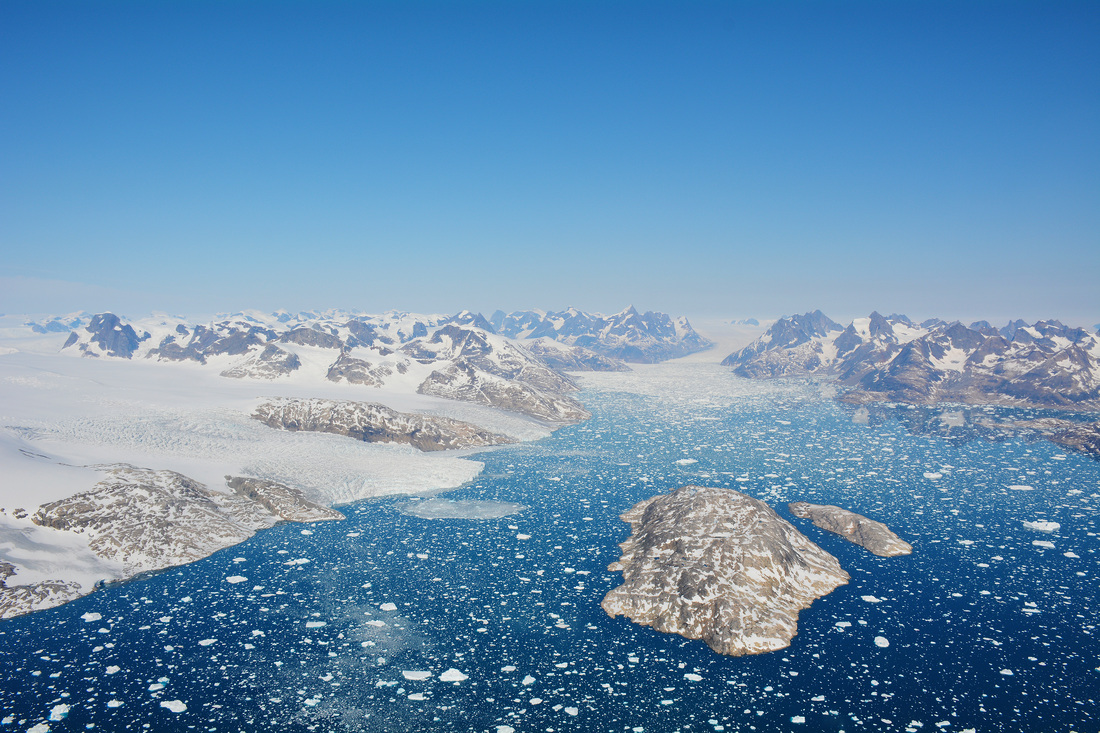

Contributing Author: Benoit S. Lecavalier The Greenland ice sheet is melting fast, and it contains enough water to raise global sea levels by over seven meters if it were to disappear entirely. However, thousands of years ago the ice sheet was much larger, with a total of 12 metres ice-equivalent sea-level. There are many questions that remain unanswered about how Greenland lost all this ice from past to present. For example: how and where did the Greenland ice sheet lose mass? What climate history resulted in such a drastic change in the ice sheet? This summer, these were the questions that led a multidisciplinary team of geologists, geophysicists, biologists, and biogeologists to Southeast Greenland. We were embarking on an expedition to better understand its climate history, and so resolve part of a much bigger story. We were going to the Arctic by ship to take advantage of the best weather it had to offer for the summer 2014 field season. As we waited in Reykjavik with our equipment, our ship - the last sailing vessel built of wood with ice plating for navigating Arctic waters - was traveling from Denmark to Iceland. It was called the Activ, and it was an old-fashioned schooner with three masts and fourteen sails. On the way to its destination, the ship had to cross the rough waters of the Denmark Strait, where we had to endure three days of seasickness. Fog descended upon the ship as we approached the Greenlandic coast. The ship navigated carefully past icebergs in search of shallow water to anchor for the evening. There was little room for error: in emergencies we depended entirely on satellite phones, and even by helicopter we were hours from the nearest town. Finally, we sailed into a fjord and found a proper place to anchor, before preparing the inflatable motor boats that would ferry us to and from our research sites. The fjords along the coast were carved over thousands of years by the expansion and retreat of the ice sheet. Because they were flooded by the sea when the ice retreated, for us they were a valuable inlet to the Greenlandic interior. We got there by motor boat, hoping to collect rock samples for cosmogenic dating. As the ice sheet receded, boulders were no longer covered by ice that had shielded them from bombardment by cosmic rays. When these particles from space blasted into the rock, specific isotopes were produced in the minerals (Beryllium-10; 10Be), and as time passed they accumulated. Today, scientists can determine how long the rock has been ice-free by measuring the quantity of Beryllium in a sample. In that way, they can infer the position of the ice sheet at a given time. At the end of the day, the motorboat was always weighed down by numerous samples, and the commute back to the ship was always long. On our return, we would weave between newly calved icebergs, often passing seals and birds, before finally arriving back home to the ship, with warm food waiting for us. After dinner, decisions were made on where to head next. With the anchor raised, the goal was usually to sail southward through the night. Night shifts were assigned so that there were always two iceberg watchers at the bow of the ship and two people on the bridge concerned with steering. At this latitude and time of year the sun barely dips below the horizon, resulting in a state of permanent twilight. On a foggy night we had to be ready in a moment’s notice to call out an iceberg, while on a clear night we could enjoy the peaceful tranquility of water and wind flowing past the ship. By early August we anchored in a bay within a major fjord in southern Greenland, with the intention of collecting samples for several days. Using the motorboat we traveled near an isolation basin, a lake that had once been connected to the ocean. Thousands of years ago, the ice sheet extended farther at the margins. The weight of the ice deformed the Earth, depressing the crust lower than it presently lies. As the ice receded, the crust rebounded, which disconnected some basins at the coast from the ocean and created new lakes. We collected cores of the sediments at the bottom of these lakes, since they document the microfossil remains of organisms (foraminifera) that inhabited the area. By dating the transition from saltwater to freshwater organisms, we discovered when the basin was separated from the ocean. Given the current elevation of the lake and time of isolation, we acquired an inference for past sea level. One morning, at the break of dawn, the water was calm yet we heard splashing by the side of the boat. A few minutes later, we left the galley and went up on deck for a day’s work. Suddenly, we noticed that the motor craft was torn and deflated with the emergency kit missing (it had included flares and chocolate, among other things). A polar bear was on the coast tearing through the kit. As we watched, the bear decided he wanted more. He dove back into the frigid water and swam towards us. In a panic we lifted the motor boats, loaded some rifles and carefully watched the bear try to get on board. The bear circled the boat again and again, like a shark. He was attempting to grab on a ridge along the boat when we decided to fire some warning shots. The polar bear quickly fled to the coast where he would remain all day, preventing us from going out and taking more samples. The days passed, we collected more samples, and we continued southward into Prince Christian Sound – a fjord complex that separates the mainland from the southernmost tip of Greenland. As we neared the end of our expedition, we finally began to encounter small isolated coastal communities. We sailed from village to village, from Augpilagtoq to Nanortalik, and then to Qaqortoq, where we officially disembarked. We helicoptered to Narsarsuaq where we said goodbye to Greenland, its vast, pristine landscape, its mountains and wildlife, and its ice. We disbanded and flew our separate ways, where new challenges awaited us. Only upon returning to our respective institutions could we begin to interpret the samples we had collected. The samples will become data, and the data will implemented in models. It is a long process which will ultimately improve how ice sheet models behave. The models must accurately simulate ice retreat to remain consistent with cosmogenic dates. They must unload adequate amounts of ice for the Earth to deform and sea level to change, to coincide with the observations from isolation basins. This procedure will retune and calibrate Greenland ice sheet models, revise their simulations of climate forcing, and increase our level of confidence in our model predictions. It began on a ship navigating never-before sampled areas of Greenland, and it ends as ones and zeros on a super computer. The aim: to better understand how the Greenland ice sheet responded to past climate change, to better predict how it might respond to a warmer future. More photographs from the Arctic:The team:Scientists:

Nicolaj Larsen Kurt Kjær Antony Long Svend Funder Benoit Lecavalier Anders Bjørk Kristian Kjeldsen Peter Ilsøe Laura Levy Anne-Katrine Faber Sarah Woodroffe Willi Winrebe Johan Spens Micaela Hellstrom Crew: Jonas Bergsøe (Captain) Jeppe Møhl Gonzalo Guarda Birk Jessing Aase Huggler Fram Arwyn P.  Contributing Author: Benoit S. Lecavalier August 18th, 2013 marked the start of a two week long workshop called the Advanced Climate Dynamics Course (ACDC). The venue was located in a former fishing village in the Vesterålen islands of Arctic Norway, a little place called Nyksund with a population of slightly over a dozen permanent residents. We were there for more than just hiking through the great outdoors, eating the local food, and performing local outreach. We were there to discuss what many call small talk: the climate. Organized by European and North American Universities, this event attracted internationally renowned researchers and graduate students, gathered there to discuss the climate dynamics of the last deglaciation. Twenty thousand years ago, during the last glacial maximum, the climate was cooler, the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheet were larger, and gargantuan bodies of ice rested across North America, the British Isles, and Scandinavia. Consequently, the sea-level was lower than it is today by over 120 meters. The emphasis of the workshop was to discuss how the climate system transitioned from glacial to present interglacial conditions. The seminars began by summarizing our present understanding of climate on time-scales of thousands of years. The driver, often referred to as the pacemaker for the ice ages, is the changes in the Earth’s orbit around the sun. These gradual changes in the Earth’s orbit affect incoming solar radiation at the Earth’s surface, which can either facilitate the growth of an ice sheet or deter it. However, countless feedbacks within the climate system render the situation complex. For example, ice sheet’s reflective nature deflects radiation back into space affecting the available energy at the surface. In addition ice sheets, which can rival mountain ranges in size, affect atmospheric jet streams and deflect storm tracks as well as precipitation patterns. To understand these feedbacks within the climate system we have to look at paleoclimate records: terrestrial and marine records of past climate. The following days were spent going over climate proxies, which preserve physical characteristics of past climatic conditions. These tell us about past temperatures on land and in the ocean, how vigorously the oceans circulated, and past sea-levels, among many other things. After being presented with collections of paleoclimate records, we could speculate on the role of the atmosphere and ocean during the deglaciation. The question that came came to mind: if the ice ages are driven by slow gradual changes in the Earth’s orbit around the sun, what processes, feedbacks, and mechanisms could punctuate the system with such abrupt and rapid climate change? We reviewed the literature to investigate the consensus on what is currently understood and what observations lack a proper explanation. Our review emphasized the necessary role of geophysical modeling of the climate system to understand how all these complex processes are intertwined. State-of-the-art atmosphere-ocean general circulation models tell us about the state of the atmosphere and ocean, while glacial system models reveal the response of ice sheet to past climate change and the resulting change in sea-level. Atmosphere-Ocean models are predominantly applied for the past and future 100 years, so the question remains: what were the climatic conditions over the ice sheets thousands of years ago? What climate forcing led to ice sheet instabilities, causing the flow of iceberg armadas in the North Atlantic? To which extent did the fresh water from these icebergs affect the circulation of the Ocean? How have these changes in circulation affected global heat transport and the carbon cycle? What about global temperatures? Fortunately, we are beginning to answer these questions thanks to international cross-disciplinary collaborations, which are often initiated by workshops such as the ACDC.

Many atmosphere-ocean modelers take an interest in simulating the deglacial climate, with help from the glaciological community who provide past ice sheet reconstructions. These scientists have discovered that massive ice sheets show the potential to deflect atmospheric stationary waves. The ice sheets respond to climatic shifts, and in warmer conditions they can change dynamically by releasing icebergs into the ocean. Fresh water melting from those icebergs produces density differences in the Atlantic Ocean which slows down the formation of heavy deep water, affecting global circulation. This change in ocean heat transport cools the North Atlantic, while the Southern Oceans warm in a compensating fashion. The models simulate these dramatic climate events, hinting at underlying mechanisms and illuminating the observations found in paleoclimate records. This goes a long way towards explaining how the Earth as a whole warmed out of the glaciation and why records in the North Atlantic reflect quick warming with subsequent rapid and prolonged cool period before finally stabilizing to present conditions. However, the story is far from understood, for every answer brings new questions. The workshop got everyone thinking about possible avenues of research which will have to be investigated to address our questions. That is why we gathered there in that little Norwegian village. It was to exchange ideas, data and model predictions, to work together and form collaborations, and to piece together a story that shaped humanity and still affects us today. |

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed