|

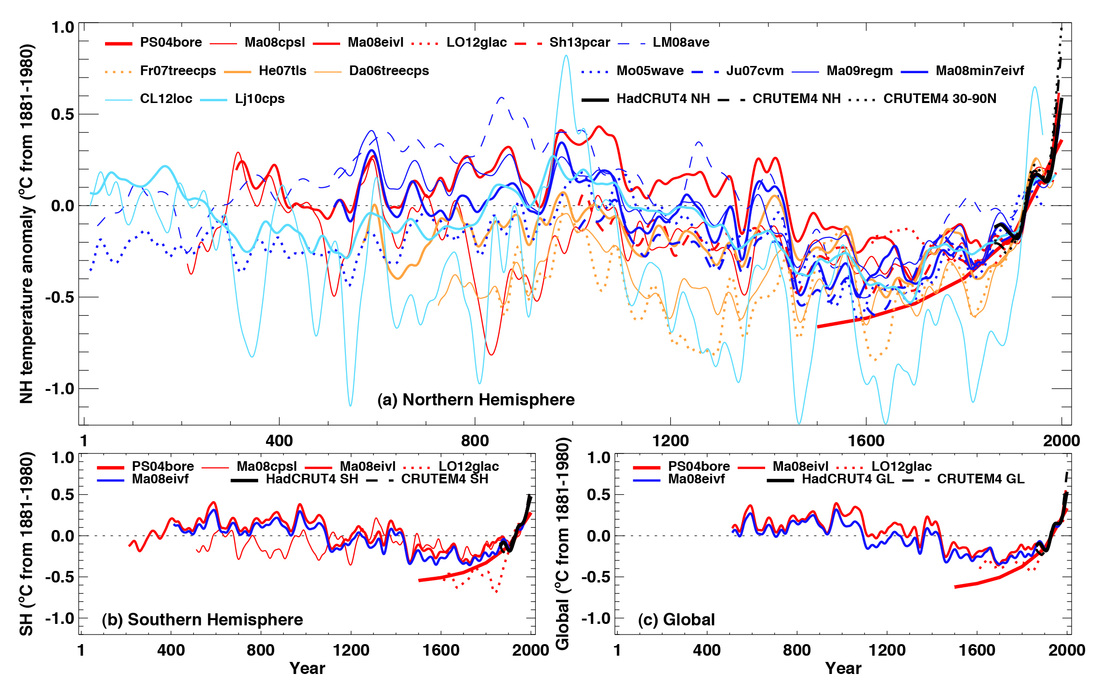

Dr. Martin Bauch, Deutsches historisches Institut in Rom. I am in the third circle, filled with cold, unending, heavy, and accursed rain; its measure and its kind are never changed. Gross hailstones, water gray with filth, and snow come streaking down across the shadowed air; the earth, as it receives that shower, stinks. - Dante, Inferno, Canto VI In the last years of his life, Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) was an unsuspecting witness to a rapid shift in climatic conditions that led to cooler and wetter weather all over the continent. Perhaps it was not by chance that in his Inferno, finished in 1314, the sinners guilty of gluttony and sent to the third circle of hell were punished by incessant cold rain, hail and snow, while squirming through foul-smelling mud that reminded contemporaries of the crops rotting on their fields. Across Europe, meteorological events in the 1310s caused harvest failures, floods, famines, and mass deaths. In particular, Dante’s description of the wet third ring of hell is very similar to weather conditions that caused famine in Italy between 1310-12, and offers a prominent clue the onset of the Little Ice Age left in Europe’s cultural heritage. Other traces of the cold, wet years appear in variety of sources: inscriptions from Central Europe which recall the thousands of starved individuals buried outside the city walls, and countless chronicles reporting death, famine, corpses on the streets, and riots linked to rising food prices. The hostile weather and massive soil erosion can also be reconstructed using scientific methods: ice cores from Alpine glaciers, sediment cores from lakes, and tree rings all reveal the rainy years that oaks all over Europe enjoyed, as these trees thrive on chilly and humid weather. Using these tools, scientists and climate historians have come to agree that climatic conditions changed seriously at the beginning of the 14th century, ending the presumed milder conditions of the so-called Medieval Climatic Anomaly and initiating the so-called Little Ice Age. When referring to the extreme wet and cool conditions in Northwestern Europe that were responsible for the Great Famine (1315-21), written sources and dendrochronological data agree that the 1310s were a decade of climatic stress. The damage of this decade, called the Dantean Anomaly by, was long thought to be restricted to the British Isles, Northern France, the Benelux countries and Northern Germany. But as not only the Inferno’s vision of hell indicates, the cool period was probably a trans-continental event. A new junior research group at headed by Dr. Martin Bauch, funded by a VW Freigeist Fellowship and based the Centre for the History and Culture of East Central Europe (Leipzig), seeks to understand the social, economic, and cultural impact of the Dantean Anomaly across Europe. The “Dantean” project will compare three geographically and climatically different regions neglected by research thus far: the Mediterranean regions around the Italian cities of Siena and Bologna; the continental climate region of the Holy Roman Empire from east of the Rhine to Poland, Moravia and Austria; and the rural plains and mountains of the Atlantic maritime climate in Southeast France, around Bresse, Pays de Gex and Savoy. These case studies differ not only climatically but by source bases, which range from urban administrative reports in Italy to the charters in the Holy Roman Empire to rural accounts and records in France. In some cases, inscriptions on buildings and archeology give further information. Narrative sources – the classical data base for climate historians so far –are abundantly available across all three regions, and provide broad chronological background for the years 1240-1360. Since a reconstruction of climatic conditions should not be limited to data from written sources, the project will be enhanced by scientific research that provides information on meteorological conditions in a high temporal resolution (dendrochronology; ice core research; warve chronologies; geomorphology). With the cooperation of several scientific partners, the project will provide the first integrated and reliable study of climatic conditions in the 1310s in large parts of continental Europe. Beyond reconstructing the frequency of extreme climate events, the “Dantean” project addresses the social, political, and economic consequences of this period across Europe. In particular, the research team is looking for the variety of social responses to extreme climate pressure. In Italy, their preliminary findings show urban areas exhibiting sophisticated responses, from building institutions to technical countermeasures and adapting agricultural and economic structures. The detailed fiscal accounts from Siena and legal and police records from Bologna show that in the 1310s, both cities faced precipitation-related and food supply crises, and as a result existing institutions grew or new ones were created to cope with the situation. Yet food-related upheavals shook the established order: documentation from Bologna allows us to trace how food scarcity contributed to criminal behavior and made social tensions rise. Yet, although Italy was hit hard by extreme meteorological events, considerably fewer people died there than in England because food management was taken seriously by the efficient bureaucracies of wealthy city states which imported grain and stored it in granaries. Moreover, Italian cities were better prepared for the climatic stress of the 1310s than societies north of the Alps: by examining the charters of the Holy Roman Empire, the “Dantean” project will examine how feudal overlords managed the destiny of their subjects and estates in a time of a natural crisis. Although the project will in all probability reveal a temporarily limited profit of grain-selling institutions by rising food prices and punctual charity provided by monasteries, coherent, systematic or enduring relief measures are were unlikely. The nobility north of the Alps simply cared less about their subjects; thus starvation and perhaps even cannibalism were the consequences. Overall, whether inhabitants in Central Europe were vulnerable or resilient to natural impacts depended very much on their social status. The situation in France was socially similar, but here the ‘Dantean” team can compare if living on the flatlands or in the mountains had a measurable impact on social responses and the impact of the cold, wet 1310s on people in the countryside.

By comparing these three regions, the “Dantean” project has great potential to advance our knowledge of vulnerability and resilience of medieval societies in regard to environmental stress. This comes mainly from its trans-regional approach. Cultural and institutional preconditions of specific societies are crucial to understand the impact of climate change; therefore the causal relationship between weather, death and famine must be investigated in relation to the economic, cultural, social and political preconditions. Existing longue durée studies on the resilience and vulnerability of pre-modern societies under ecological stress cannot confidently confirm a close connection between extreme events and social change, since the pace of change and the occurrence of natural events cannot be synchronized. Only chronologically limited case studies will provide insight into short-time reactions to natural extreme events – an approach that has hardly been employed until now. These examples underline that there are always winners and losers of climatic change – not only in the 21st century but also in the Late Middle Ages. The JRG will start its work on 1 March 2017, till then you can contact M. Bauch via [email protected]

64 Comments

10/27/2022 10:33:22 pm

Sometimes I get confused, but after reading your post, I can think of the best alternative. It's amazing. You're helping me a lot. Thank you very much. 토토사이트

Reply

11/7/2022 09:38:41 pm

I've been looking for photos and articles on this topic over the past few days due to a school assignment, <a href="http://clients1.google.com.au/url?sa=t&url=https%3A%2F%2Foncainven.com">bitcoincasino</a> and I'm really happy to find a post with the material I was looking for! I bookmark and will come often! Thanks :D

Reply

11/18/2022 11:51:23 pm

"Hello, i think tһat i saw you visited my site so i came to “return the favor”. I'm trying to find things to improve my website! I suppose its ok to uѕe a few of your ideas!! Thank you!!

Reply

11/18/2022 11:51:44 pm

"I think the aԁmin of this website is actually working hard in favor of his web page, as here every data is quality based information. Please visit my page and join online casino community:

Reply

11/18/2022 11:52:00 pm

"Daebak!! This has been an incredibly wonderful article. Thanks for supplying this information. Great website. A lot of useful information here. check out the given link below and sign up now:

Reply

11/18/2022 11:52:19 pm

Aw, this was an exceptionally good post. Taking the time and actual effort to create areally good article.. but what can I say.. I put things off a whole lot and never manage to get anything done.

Reply

11/19/2022 08:26:41 pm

I am really happy to say it’s an interesting post to read. I learn new information from your article, you are doing a great job. Keep it up!

Reply

11/20/2022 10:47:43 pm

From some point on, I am preparing to build my site while browsing various sites. It is now somewhat completed. If you are interested, please come to play with <a href="http://maps.google.ro/url?sa=t&url=https%3A%2F%2Fevo-casino24.com">baccarat online</a> !!

Reply

12/8/2022 12:31:57 am

That is a really important issue in the modern world. Thank you very much for sharing this post, I appreciate your work. It was a very informative post. Find many useful and informative links.I liked your writing, too. The concept of the subject was well discussed. I want to come back here. Thank you so much for writing such a good article. 메이저토토

Reply

jaeseu

1/13/2023 08:29:11 pm

Thanks for such a pleasant post. This post is loaded with lots of useful information.

Reply

I don't know if it's just me or if other people are having problems with your blog. Some text within the content appears to be running on the screen. Can someone else leave a comment and let them know if this is happening? This problem has occurred before, so there may be a problem with your web browser. Appreciate about that. 사설토토

Reply

1/24/2023 08:10:09 pm

Hello! This post couldn't have been better written! Reading this post reminds me of my old roommate! He was always chatting about this. I will forward this report to him. I'm pretty sure he'll read a good book. Thank you for sharing! 머니상상

Reply

5/27/2023 03:57:55 am

A nice value post has been presented. I liked your website and think it's a good resource for women looking for dresses. I really appreciate you sharing.

Reply

5/27/2023 03:59:37 am

This post has a wonderful value. I liked your website and think it's an informed dress drip for women. I appreciate you sharing, very much.

Reply

5/27/2023 04:00:45 am

The article is really worth sharing. Your website is a great resource for women, and I really enjoyed visiting it. I appreciate you sharing this,

Reply

5/27/2023 04:02:28 am

It's a fantastic post with good value that was shared. I liked your website and think it's a well-informed clothing drip for women. Thank you very much for sharing.

Reply

5/27/2023 04:06:13 am

Glad to see your post, by the way.The most lovely and fascinating thing I came upon.I'm overjoyed to have found your post.

Reply

5/27/2023 04:07:49 am

I'm very Your post makes me very happy.The most lovely and exciting thing was what I discovered.glad I stopped by your post.

Reply

5/27/2023 04:08:50 am

I'm very Your post makes me very happy.The most lovely and exciting thing was what I discovered.To visit your post makes me so pleased.

Reply

5/27/2023 04:12:24 am

"I really like your blog! I have the following suggestion for you. Simply click the link:

Reply

5/27/2023 04:13:36 am

"Your blog is really fascinating! You should click the following link, which I've recommended for you:

Reply

5/27/2023 04:15:47 am

"Your blog is incredibly fascinating! Please click the link below to view my suggestion:

Reply

5/27/2023 04:17:24 am

"Your blog is really fascinating! You should click the following link, which I've recommended for you:

Reply

6/7/2023 10:55:05 am

biogaming vip เทคนิค บาคาร่า ใช้ได้จริง รู้ไว้ทำกำไรชัวร์

Reply

6/20/2023 03:26:49 pm

Thanks for sharing beautiful content. I got information from your blog.keep sharing

Reply

6/28/2023 11:05:24 am

Thanks for sharing beautiful content. I got information from your blog.keep sharing

Reply

7/24/2023 04:05:12 am

Your examination is incredibly interesting. If you need that could be played out slot deposit pulsa, I like to advise taking part in upon reputable situs slot pulsa websites on-line.

Reply

10/24/2023 12:48:49 pm

If you have the best Cricket ID, online gambling and sports betting are a breeze. If you follow the advice given here, you should notice an improvement in your output.

Reply

7/24/2023 04:05:49 am

In any case I’ll be subscribing for your rss feed and I am hoping you write again very soon!

Reply

8/18/2023 03:54:21 am

Your blog always offers valuable insights that I look forward to.

Reply

pgslot168z

8/26/2023 12:03:09 pm

I will right away take hold of your rss feed as I can not to find your email subscription link or newsletter service. Do you have any? Please permit me know in order that I may just subscribe. Thanks.

Reply

9/17/2023 05:38:58 am

Really Cricket Lover. Connected with us and get <a href="https://www.getonlinecricketid.com/">Online Betting ID</a> to play online cricket betting and win big!

Reply

9/30/2023 09:37:04 am

Searching for a premier resort in Jaipur that guarantees top-notch amenities and exceptional services? Your quest ends with Lohagarh Fort Resort! Reserve your stay now for an unforgettable and enriching experience.

Reply

9/30/2023 12:31:07 pm

Heritage Hotel in Jaipur For Wedding

Reply

This is really great and useful information for people in the industry, including myself. I am glad you shared this useful information with us. Please give us the latest news like this. Thanks for sharing. This is a really good product. 메이저토토사이트 https://small-tits.info

Reply

10/19/2023 07:56:15 am

By creating an Online Cricket ID, you may safely and securely participate in the exciting world of online betting and gambling. It's possible that your success rate will increase as soon as you figure out why this is the favorite option of cricket lovers.

Reply

10/24/2023 12:56:28 am

This book will help you navigate the vast and complex realm of online gaming. Casino play and sports betting are both available for gamblers' satisfaction.

Reply

10/24/2023 12:49:30 pm

If you have the best Cricket ID, online gambling and sports betting are a breeze. If you follow the advice given here, you should notice an improvement in your output.

Reply

10/26/2023 05:35:23 am

The gambling and betting communities would greatly benefit from implementing Betting ID. As word of the great service spread, the restaurant quickly became packed. The cricket match is the safest place to place a wager. Five of the most common justifications are listed below.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

August 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed