|

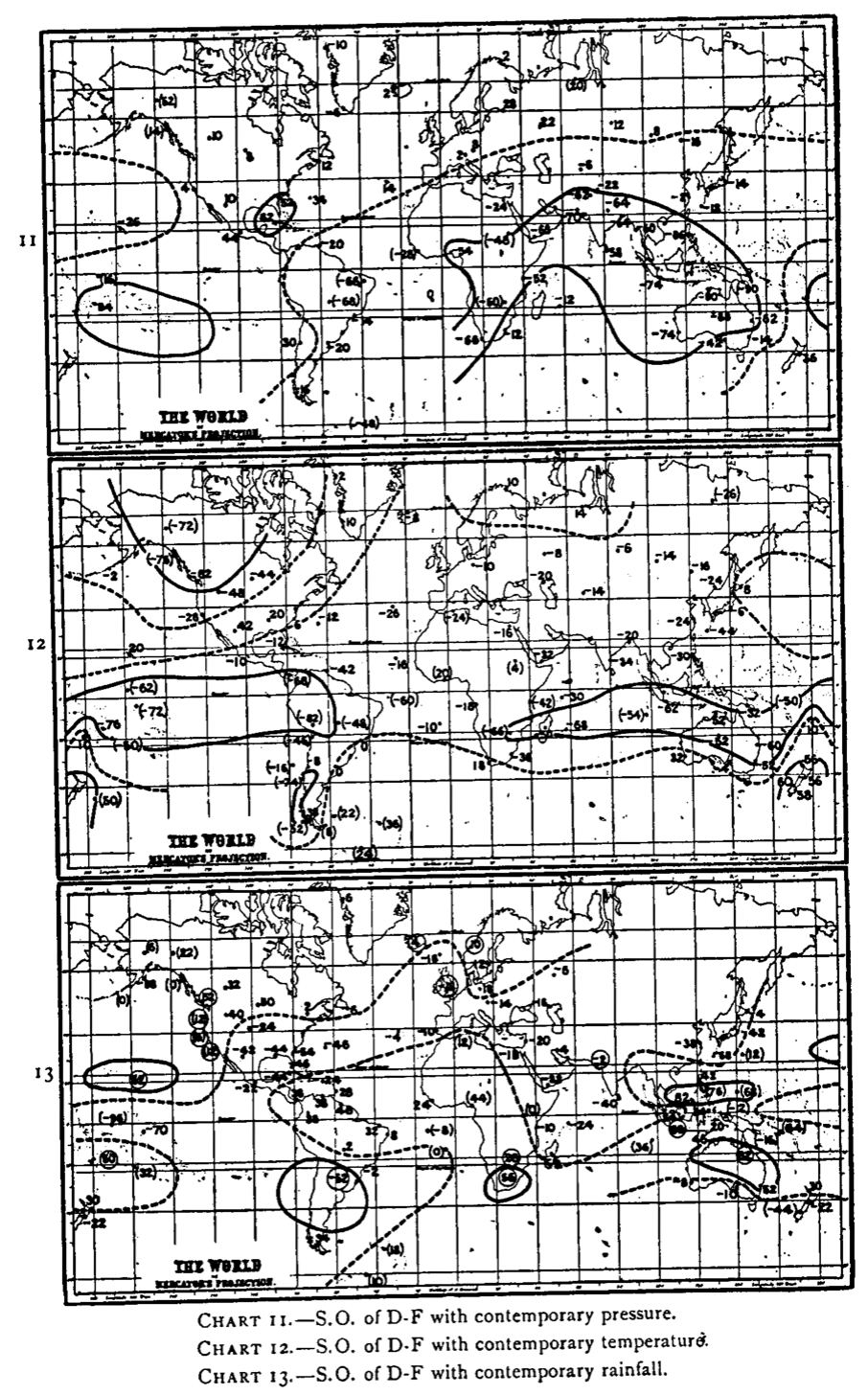

George Adamson, King's College London When Gilbert Walker codified the Southern Oscillation in the 1920s, he did not define a causal mechanism that could explain weather variability in other parts of the world. Rather, Walker’s Southern Oscillation was the application of a branch of statistics that Walker himself developed, his analysis revealing a co-relationship in pressure between weather stations in the eastern and western Pacific. Walker’s Southern Oscillation wasn’t tied to a particular place – the meteorological stations from which the analysis was taken were in locations as diverse as Cape Town and Southeast Canada – and it had no underlying mechanism, although he tentatively suggested a role for the Pacific Ocean. The first writings on the El Niño likewise offered no underlying mechanism for the phenomenon. In fact, the El Niño was first described not as a periodic movement of warm water across the Pacific, but as an annual warm-water current that occurs off Northern Peru around Christmas, hence El Niño (the Christ Child). Its rarer manifestations, as seen in 1891 and 1925, gained international interest to the extent that the annual El Niño current was largely absent from scientific texts by the 1950s, but the first mechanism suggested for the phenomenon – by German oceanographer Gerhard Schott in 1932 – described it as an intensified manifestation of the annual cycle. These stories draw attention to the importance of history in understanding climate variability and its associated hazards today. Science is too-often presented as a story of linear progress: in this case the discovery in the 1960s by Jacob Bjerknes that the Southern Oscillation and El Niño were manifestations of the same phenomenon (El Niño Southern Oscillation, ENSO), and the eventual development of successful forecasts. Understanding the history of El Niño science, however, reveals a more complex picture. As Greg Cushman has shown, geopolitical interests were as important as their scientific counterparts in driving research in the central Pacific during the Cold War. Bjerknes’s model provided the impetus for new studies of ocean-atmosphere dynamics; it also launched El Niño as a trendy scientific area, bringing in scholars from several disciplines who rebadged their previous research in the process. This accelerated in the 1980s when it was discovered that the central Pacific could be represented in relatively simple models, and that the outputs of these models could inform applications in hazard monitoring and (profitable) commodities forecasting. Media-friendly El Niño events such as 1982-83, 1997-98 and 2015-16 have further increased interest in El Niño/ENSO. Media coverage has helped to cement the idea of El Niño as a bounded climatic entity with almost god-like capacities of global devastation. In the 1980s, El Niño became personified, as years with opposite sea surface temperature anomalies were codified as ‘La Niña’, presenting ENSO as a dualistic entity with both male and female characteristics. Meanwhile, retrospective attempts to quantify El Niño into a single definition in the wake of the 1997-98 event have led to confusion and fragmentation. There is now a growing list of ENSO ‘flavours’, each constituted by characteristic warming and cooling patterns and each apparently distinct from the others. This includes recent suggestions that the atmospheric Southern Oscillation may sometimes act independently of the ocean (the ‘thermally coupled Walker mode’), and that tropical Pacific ocean variability may not be coupled with changes in the atmosphere (‘uncoupled warming’). The implications of this fragmentation were shown starkly in 2017, when heavy flooding hit northern Peru. That year, while Peru’s coast experienced the ocean warming characteristic of El Niño, no similar changes occurred in the central Pacific, confounding recent definitions. The absence of a forecast ‘El Niño’ that year is one reason for the devastation caused by the flooding, particularly as the ‘severe’ El Niño one year prior had not brought the expected rainfall. The event was later codified as a ‘coastal’ El Niño. Subsequent historical work in historical climatology has suggested that the 1891 and 1925 events may also have been coastal. Hence the incidents that precipitated global research on El Niño would not have been classified as such 100 years later. All of this demonstrates the importance of taking a historical approach. The concept of ENSO as a single entity characterised by variability in the central Pacific may seem self-evident to those whose first exposure to El Niño was on the news in 1998, but historical context shows that the phenomenon has had several meanings, and that today’s singular El Niño was shaped as much by scientific culture as by scientific evidence. Moreover, history reveals the continued importance of geopolitics in understanding climate risk. The fact that El Niño is now associated with the central rather than eastern Pacific was driven in part by that region’s importance in regulating weather over north America. This change in definition was undoubtedly influenced by the dominance of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration over global understanding of ENSO, obscuring other readings of the phenomenon, including the annual El Niño still anticipated by north Peruvian fishermen each year around Christmas.

It is possible that future scientific research will indeed show ENSO to be a single phenomenon, proving that all flavours of ENSO – including the coast El Niño – are related to a single underlying dynamical process. But in the meantime, it is important to be mindful of ENSO’s historical complexities. Scientific phenomena that seem self-evident rarely are so, and understanding their political history is as important as appreciating the advances of previous generations of scientists. Finally, this brief account draws attention to the importance of historical climatology as a discipline. Whereas other disciplines tend to be specific to the physical or social sciences or humanities, historical climatology combines an appreciation of positivist science with an attentiveness to history and culture. Approaching an issue as complex as climate science – and particularly climate change – from such an inherently interdisciplinary lens can illuminate problems in a fairly unique and important way, as ENSO’s complicated history shows.

195 Comments

|

Archives

August 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed