|

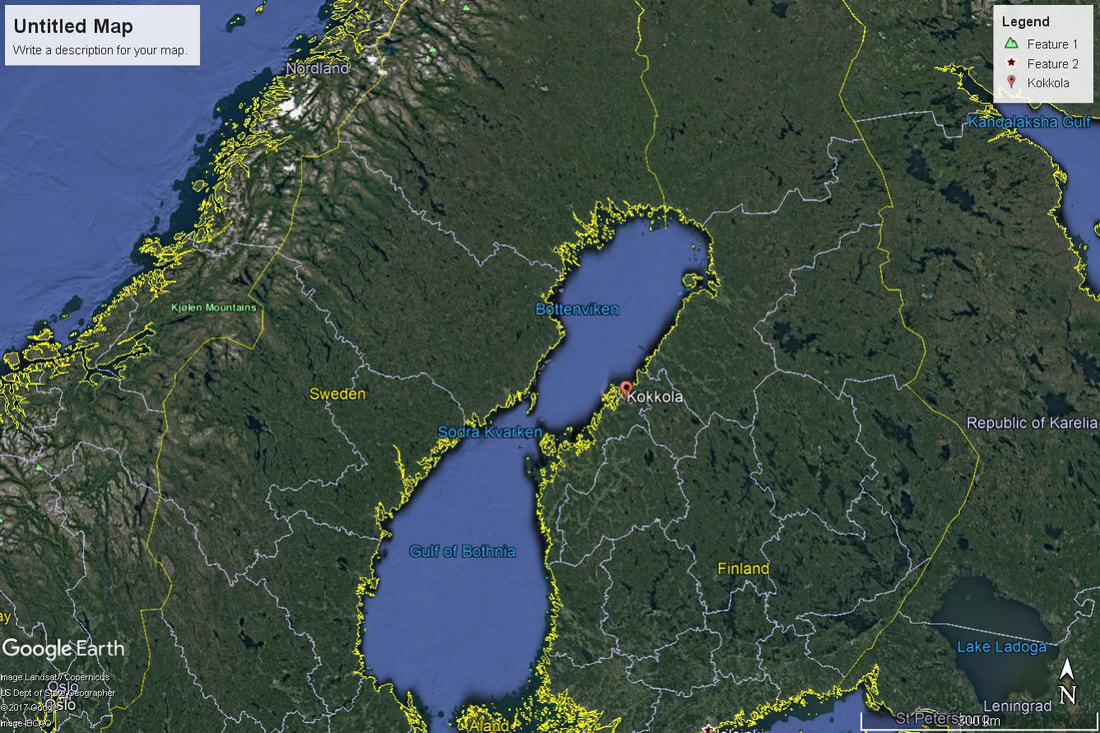

Laura Eerkes-Medrano, University of Victoria This past winter I was fortunate to join the Arctia Otso icebreaker in the Gulf of Bothnia, Finland, from March 2 to March 24, 2017. I had sailed the Northwest Passage aboard the Canadian Coast Guard ships Sir Wilfrid Laurier and Louis S. St-Laurent in 2015. Going to Finland to travel on an icebreaker for 20 days was my next big step as a Canadian scientist. My goals were to observe how changing ice and weather conditions affect marine shipping operations, and to learn more about the human element in terms of how the crew use instruments and information to make decisions. I also hoped to learn what additional weather and sea-ice information, and in what format, would be useful for improving weather and sea-ice forecasting, ultimately contributing to safer shipping activities. A common challenge when preparing to join an icebreaker in Canada is to determine the exact date the ship will arrive in port. Difficult ice and weather conditions can prevent the ship from arriving at the specified date. In the Gulf of Bothnia, since distances are shorter than they are in Canada, icebreakers generally will arrive at port on the predetermined date, but changes in weather and ice conditions may affect the operational area for a ship, meaning it may go to a different port for fuel replenishment and crew changes. As I was flying from the west coast of Canada to Finland in winter, I had to allow a couple of days on either side of the Otso’s planned arrival in case the port location changed or my plane was delayed by weather. Once on board the Otso, the first thing I learned was that, with less sea ice, paradoxically, there is more work for icebreakers. In the past, ice would form in the Bay of Bothnia in October or November. Although a declining sea ice average has been observed in recent years, the trend is not linear. Mild winters were also observed in the 70s and 80s. With less sea ice cover, new thin ice is constantly forming. This ice is broken up by winds, and because the thin ice floes are very mobile, fractures in the ice cover (leads) and pressure ridges, resulting from the interaction of ice floes colliding with each other, are constantly forming, depending on how the wind blows. More ridge formation means that there are more vessels getting stuck in these ridges and requiring assistance.  In recent years, the pattern of ice formation has changed, and new thin ice is constantly forming. Pressure ridges, resulting from the interaction of ice floes colliding with each other, are constantly forming, depending on how the wind blows. More ridge formation means that there are more vessels getting stuck in these ridges and requiring assistance. (Photo credit: LEM. March 2017, Gulf of Bothnia) During this past winter (2016–2017), the sea ice in the Bay of Bothnia, the northernmost part of the gulf, was particularly problematic. The warm temperatures of early winter meant ice formation did not start until early January. This late ice formation gave the south and southwest winds of the January storms a longer fetch. These winds pushed the shuga—lumps of new spongy ice a few centimeters across that tend to form in rough seas—and slush ice to the northern part of the bay, where they piled up, forming a shuga-belt. This belt was several kilometers wide and a few meters deep. The stickiness and the thickness of this shuga-belt caused problems for shipping. Each vessel needed about five to six hours of icebreaker assistance to cross the belt. This contrasts with a more typical winter, where crossing the shuga that forms at the ice edge usually takes about an hour. Weather, wind in particular, is an important element in the icebreaker business. On March 2, the day I arrived, traffic in the northern Gulf of Bothnia was completely dependent on icebreaker assistance to reach the ports of Tornio, Kemi and Oulu. The tracks opened by the icebreakers would not stay open for long due to the strong winds from the south. At the same time, there was not much ice to break in Kokkola, since all the ice had been pushed to the north. Visibility is another factor when assisting a vessel. In foggy conditions it is often hard to determine exactly how close the moving vessel is, even with the use of radar. Luckily the crew on the Otso are highly skilled in ice navigation in all weather and ice conditions. They were able to make very good decisions about what approach to take—either breaking the ice or offering a tow—when assisting a vessel. In the past, forming a convoy was the preferred option for assisting vessels in this environment. This is now less frequently a choice. The vessel tracks do not remain open because the wind, gaining strength over the long fetch of open water, pushes the ice floes against the shore ice, forming ridges and compressed areas, making navigation difficult. Vessels waiting for icebreaker assistance also face an additional threat that can add a time pressure on operations. In the past, a beset vessel would simply remain in the ice while waiting for an icebreaker. Now, under conditions of thinner, more mobile ice, there is a greater danger of a beset vessel drifting towards shallow areas. To ensure safety drifting vessels are given higher priority, which often means assisting them one at a time instead of using the convoy approach. The icebreaker’s response to vessels in need of assistance depends on the circumstances. Every situation is different, and various factors need to be considered when making the decision, including the type of event, the beset vessel’s ice class, the training and experience of its crew, how the crew on the assisted vessel are maneuvering and how they are using radars and instruments. It also depends on the instruments and information available to the icebreaker crew, and the accuracy of that information. Depending on the wind speed, the icebreaker crew could decide to assist a vessel. However, if the wind is blowing at 25 m/s or more, the icebreaker will not move; it is unsafe to assist vessels under these conditions due to the possibility of ice drifting and ridging, and the chance the track opened by the icebreaker will not remain open long enough to assist the vessel.

The main criteria in the decision to respond is safety and the timeliness of delivering assistance. Other factors that Arctia icebreakers consider are fuel consumption, the number of vessels an icebreaker will be able to assist per trip, and the efficiency of icebreaker operations. The Otso’s crew always strive to find ways to do things better while maintaining quality and remaining competitive. This was a great learning experience and an example of the industry-academia partnerships supported by Tom Ekegren, senior vice president at Arctia Icebreaking Ltd., and the Marine Environmental Observation Prediction and Response Network (MEOPAR). This project was funded by MEOPAR, a Canadian Centre of Excellence. Captain Duke Snider at MartechPolar has been a key supporter of this project and facilitated this opportunity with Arctia Ltd.

185 Comments

|

Archives

August 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed