|

Matthew Hannaford, University of Lincoln Figure 1. Fort of Sofala (Mozambique) from Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg's atlas Civitates orbis terrarum, vol. I, 1572. In their Companion to Global Environmental History, John McNeill and Erin Mauldin argue that "Consciously or unconsciously, scholars provide scholarship for the times in which they live.” Certainly, it would be hard to argue that environmental historical scholarship is written in ignorance of the “ecologically dynamic and globalizing times” in which we live. Yet begin to break this down and the picture becomes more complex. Take historical climatology, and pose the question: ‘to what extent can the field provide critical interrogations of the discourse on present-day and future climate change and adaptation?.’ The answer may not be so controversial, and arguments have been made by Mark Carey, Georgina Endfield and others that do precisely this. Push it a step further, though, and consider whether and how the field can inform climate adaptation policy and practice, then there is not necessarily a straightforward answer. In an article published in Global Environmental Change in 2018, George Adamson, Eleonora Rohland and I sought not only to address this question, but also to elaborate on the important contribution that historical climatology and history more broadly can, and, we argue, should make to climate change adaptation research. This post provides a summary of our argument, with links to my own work in southern Africa. If we start by looking at the first major objective of historical climatology (as defined by Christian Pfister, Rudolf Brázdil, et al.) – “to reconstruct weather and climate prior to the modern instrumental period” – the answer to both of the above questions would appear relatively clear-cut. Few would dispute that long-duration baselines of climate variability provide essential context to changes taking place over recent decades. Yet if we consider objectives two (“to investigate the vulnerability of past societies and economies to climate variations”) and three (“to explore past discourses and social representations of the climate”), the waters become muddied. Indeed, despite a resurgence in research on these latter two objectives over the last decade or so, there is little evidence of what we refer to as ‘mainstream climate change research’ (loosely defined as that included within IPCC WGII) adopting insights from historical climatology. That is to say, although much research in historical climatology has been informed by theoretical advances in climate change research, for example through concepts like vulnerability and resilience, there has arguably been little influence in the other direction. Instead, where historical climate-society interactions have been discussed within climate research, this has largely come from those without historical training. For example, temporal analogues of climate-society interactions have been utilised by social scientists and paleoclimatologists as a way to understand how human systems manage and experience climate risks, to identify successful and non-successful adaptations, and to understand the processes that shape vulnerability. However, these analyses have been open to criticisms of reductionism, through overplaying similarities and understating differences between past and present, as well as criticisms of determinism through their oversimplification of complex processes. Equally, Social-Ecological Systems (SES) analyses, driven by the IHOPE (Integrated History and Future of People on Earth) network, advocate the integration of historical data into systems models in order to identify ‘safe and just’ spaces for humanity to operate within. Yet SES has been criticised for focussing on the ecological, economic and technological dimensions of adaptation, and as a result downplaying human and political agency. Similar critiques exist for quantitative historical research on climate and conflict. It is all very well for historians to label these approaches as deterministic or reductionist, but what of historical approaches that counteract these criticisms? In the article, we argue for three interventions:

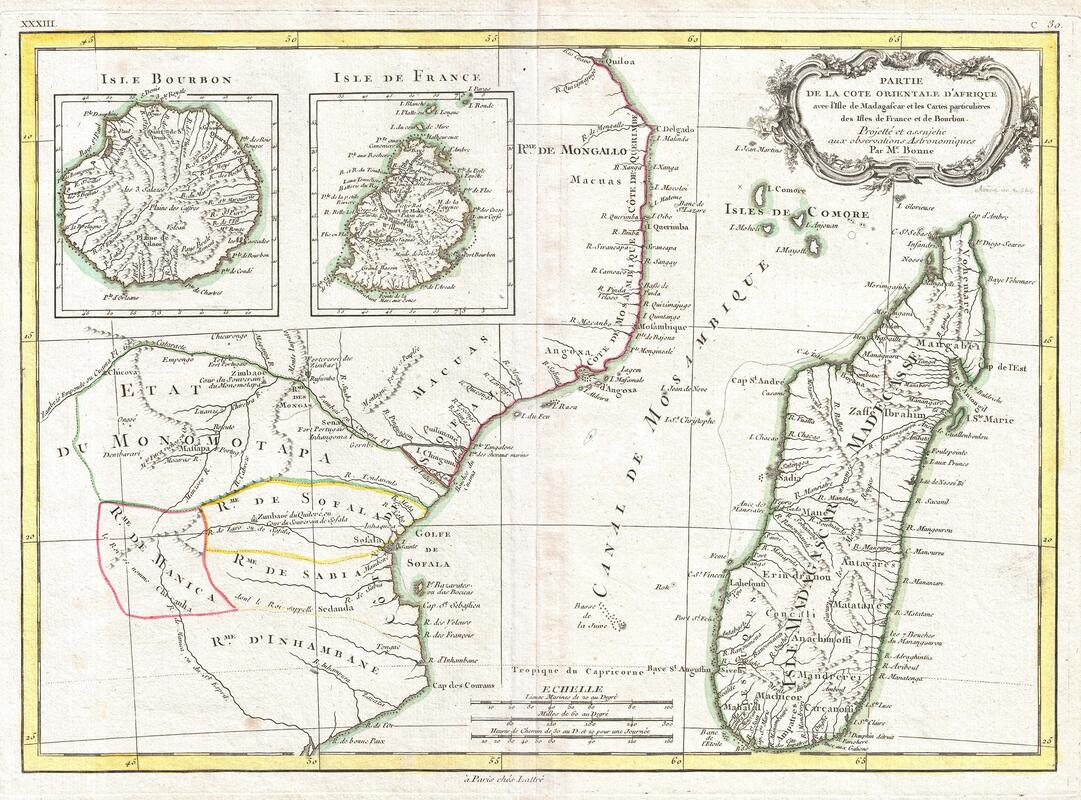

Each of these approaches is underpinned by a focus on the narrative side of history, based upon fine-grained analyses of extensive corpora of archival records, which brings into focus the role of individual and institutional agency, as well as the significance of uneven distributions of power in past adaptation processes, over long historical trajectories. What does this mean in practice? Let us take the example of institutional path dependency. Here, we are interested in the question of why institutional responses to climate-related extremes – recurrent in a particular place – may fail, and more generally why institutions act in a suboptimal manner, for example by blocking decisions that could be adaptive. Many present-focussed studies on barriers to adaptation simply point to factors like inadequate financial resources, overlooking the complex historical trajectories of institutions governing climate adaptation and their effects on the vulnerability of societies. On the contrary, path dependency theory argues that the policy and practice of institutions today can be driven by past decisions and historical ‘critical junctures’ – initial choice points that become locked-in and difficult to shift – and by memories of what were considered normal or successful responses in the past, regardless of their effects on vulnerability. The problem at the moment is that empirical information on the long-term evolution of institutions involved in climate adaptation governance is rather limited. This means that it is difficult to observe path dependence and change ‘in the making’, or more basically to map the extent to which contemporary adaptation is really informed by historical processes. This poses particular challenges in contexts with colonial histories, where many of today’s adaptation-related institutions were initially formed under colonial governance, and so reflected the inherent power imbalances within these societies at different points in time. In turn, legacies of these initial critical junctures may constrain the use of resources and perpetuate unequal social and economic outcomes through time. My own work in southern Africa has demonstrated this process during the pre- and early-colonial period from the 16th to 19th centuries. In the lower Zambezi valley, increased diversity of agricultural systems (amongst other factors) through the spread of wheat and maize was enough to reduce sensitivity to short-term droughts at the height of the dry 17th century. Yet local institutional factors, intricately bound up within the nature of Portuguese colonialism in southeast Africa (notably the prazo (estate) system of landownership, the growth of absentee landownership and the related growth of responses to stress that provided short-term gain over long-term stability), ultimately overrode reduced vulnerability derived from material factors. These slow-moving, endogenous factors combined with a period of severe and prolonged drought to produce the calamitous famine that raged on the lower Zambezi between 1824-1830. A short-term focus on the few years preceding this individual disaster could nevertheless paint an entirely different picture of its causes. Figure 2: The Portuguese settlement at Sofala in 1505 was a key critical juncture in the history of southeast Africa, paving the way for settlement up the Zambezi. This is Rigobert Bonne's c. 1770 map of southeastern Africa and Madagascar. Extending this long temporal trajectory further into the colonial period may yet reveal continuities as well as changes through to present adaptation challenges. Crucially, there is a point of interface here with the emergent notion of adaptation pathways, or ‘pathways of change and response’, within the climate change adaptation literature, which has recognised the importance of deep time perspectives. Testing the concept of path dependency in the context of climate adaptation today therefore appears to be a genuine opportunity for innovative research, and for developing a new interdisciplinary approach to researching climate change adaptation. Figure 3: The addition of winter wheat (right) to the long-standing summer season crop mix of sorghum (left) and pearl millet (middle) reduced sensitivity to less protracted droughts; however, more protracted droughts were met with institutional responses that provided short-term gain to Portuguese landowners at the expense of the long-term stability of the system. References:

Adamson, G.C., Hannaford, M.J. and Rohland, E.J., 2018. Re-thinking the present: The role of a historical focus in climate change adaptation research. Global Environmental Change, 48, 195-205. Brázdil, R., Dobrovolný, P., Luterbacher, J., Moberg, A., Pfister, C., Wheeler, D. and Zorita, E., 2010. European climate of the past 500 years: new challenges for historical climatology. Climatic Change, 101(1-2), 7-40. Carey, M., 2012. Climate and history: a critical review of historical climatology and climate change historiography. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 3(3), 233-249. Degroot, D., 2018. Climate change and conflict. In The Palgrave Handbook of Climate History (pp. 367-385). London: Palgrave Macmillan. Endfield, G.H., 2014. Exploring particularity: vulnerability, resilience, and memory in climate change discourses. Environmental History, 303-310. Hannaford, M.J., 2018. Long-term drivers of vulnerability and resilience to drought in the Zambezi-Save area of southern Africa, 1505–1830. Global and Planetary Change, 166, 94-106. McNeill, J.R., Mauldin, E.S. 2012. A Companion to Global Environmental History. London: Wiley. xxi. Pfister, C., 2010. The vulnerability of past societies to climatic variation: a new focus for historical climatology in the twenty-first century. Climatic change, 100(1), 25-31. Wise, R.M., Fazey, I., Smith, M.S., Park, S.E., Eakin, H.C., Van Garderen, E.A. and Campbell, B., 2014. Reconceptualising adaptation to climate change as part of pathways of change and response. Global Environmental Change, 28, 325-336.

4 Comments

|

Archives

August 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed