|

Eva Jobbová, Arlene Crampsie, Conor Murphy, Francis Ludlow, Robert McLeman, Csaba Horvath  Oak sample from Deer Park townland, Antrim, Northern Ireland, with rings spanning the well-known climatic downturn, c.536-550. The year 532 is marked, after which the rings become noticeably narrower. The real anomaly however begins in 536 and runs into the 540s. This oak sample can be seen in full in the top left inset, while the top right depicts a mature contemporary oak, the “King’s Oak”, on the Charleville Estate, Co. Offaly, Ireland. We thank David Brown for permission to photograph this sample. Before the summer of 2018, had you asked an Irish person to describe a drought, you might well have received a bemused response that rain and floods are a more common problem in this part of the world. But on July 5th that summer, the Irish Times declared that: The vast majority of the country officially enters a state of 'absolute drought' today with no rainfall recorded at 24 out of 25 weather stations during the last two weeks. The extreme weather conditions have prompted Irish Water to expand a hosepipe ban from the Greater Dublin Area to the whole country from Friday morning. The summer of 2018 left memories of low river levels, brown fields, unusually warm and sunny weather, cash-strapped farmers, and the infamous ‘hosepipe ban’ when authorities encouraged people to report on any neighbours who dared water their gardens with a hose. Was 2018 an anomaly, or a taste of things to come in a changing climate? Were droughts common in Ireland’s past, and have they simply been forgotten? If so, what can we learn about their impacts, and can such knowledge help us be more prepared in the future? These are some of the questions that our Irish Research Council funded project, Irish Droughts: Environmental and Cultural Memories of a Neglected Hazard, attempts to answer. [1] By combining new oral histories with existing climatic records, tree-ring data, historical documents and folklore, we aim to reconstruct Ireland’s drought history, and examine their severity, geographical extent and impacts from the medieval period to the present. “Drought-free” Ireland: simply a myth? The perception of Ireland as a soggy “drought-free” island is based at least partly on the anomalous lack of severe droughts over much of the last thirty years. But longer-term rainfall records, reconstructions from natural archives, and historical documents all indicate that multi-year periods with limited precipitation have occurred repeatedly in Ireland over the past two millennia, particularly in eastern to southeastern regions. [2] Many cultures have observed and kept records of the weather, especially the extreme events that had adverse impacts on their livelihoods, stood out from the “ordinary”, or held some special significance for understanding the natural world and the place of humans within it. The Irish were no exception, and their tradition of keeping yearly chronicles dating back to at least the sixth century, known collectively as the Irish Annals, involved frequent reporting of weather. [3] These sources thus allow researchers to identify the frequency and severity of droughts, and how people attempted to mitigate the impacts. For example, a thousand years ago it was recorded that: Much inclement weather happened in the land of Ireland, which carried away corn, milk, fruit, and fish, from the people, so that there grew up dishonesty among all, that no protection was extended to church or fortress, gossipred or mutual oath, until the clergy and laity of Munster assembled, with their chieftains, under Donnchadh… the son of the King of Ireland, at Cill-Dalua [i.e. Killaloe, County Clare], where they enacted a law and a restraint upon every injustice, from small to great. God gave peace and favourable weather in consequence of this law. Annals of the Four Masters, 1050 CE. [4] Weather recording was not the sole purpose of Irish annalists, of course, and so their documentation of extreme weather events, though remarkable for its chronological span, is for this and other reasons incomplete. It is also sometimes coloured by the ways in which such events were perceived, or how they could be interpreted for religious or political motives, as suggested by the case of 1050 above. [5] One way to fill the gaps and supplement written descriptions is with data from natural archives. Most prominently for Ireland, the oak tree-ring records compiled by Mike Baillie, David Brown and others at Queen’s University Belfast, reveal annual growing-season conditions for the past seven millennia for much of Ireland. [6] Years of unusually low growth, registering through especially narrow rings, can identify periods of extreme drought, some of which coincide with written accounts in the Irish Annals of major societal stress such as famine and mass human and animal mortality. This is true for the year 1050, with the oaks firmly indicating severe drought, while the written description is ambiguous as to the exact weather conditions involved. [7] Our cover image shows a sample of medieval Irish oak preserved for over 1500 years in acidic Ulster bog waters. Regular annual growth rings are clearly visible here, running “horizontally” up to the labelled year 532, shortly after which the tree began to grow poorly, and particularly so in the 540s. These narrow rings likely reflect poor growing conditions associated with a global climatic anomaly that began in 536 and continued until c.550, most likely caused by multiple, closely occurring volcanic eruptions (dated c.536, c.540 and c.547), and linked to famines and mortality in written sources from Ireland to China. [8] This event, usually described in terms of its temperature impacts, likely also impacted rainfall, as indicated here by the reduced growth of the precipitation-sensitive oaks, consistent with our evolving understanding of the hydroclimatic impacts of explosive eruptions more generally. [9] That the Irish oaks tend more generally to register the latter volcanic eruption in c.540 but not clearly the first major event in c.536, highlights the complexity of region- and species-specific tree growth responses, and the benefit of complementing such evidence with documentary data. [10] Drought in the recent past While sources such as the Irish Annals and Irish oaks provide the majority of our evidence for drought occurring on annual and inter-annual time-scales before the Early Modern Period, our knowledge of Irish weather, climate and environment is transformed during the 1700s with an exponential increase in the number of surviving archival sources, many of which were specifically created to report weather conditions (such as weather diaries), along with the addition of the instrumental records. Precipitation observations from 1711 taken in Derry by Dr. Thomas Neve are amongst the earliest in northwest Europe. Dr. Neve’s diary is also one of the earliest surviving weather diaries to include instrumental data on air pressure, temperature, and rainfall, and provides written observations of snow, frost, hail, thunder, and other general comments on weather. [11] By combining these sort of weather records, it is possible to reconstruct statistically representative continuous rainfall series from which droughts can be identified.These include island-wide, multi-year droughts during the periods 1854–1860, 1884–1896, 1904–1912, 1921–1923, 1932–1935, 1952–1954 and 1969–1977. [12] The droughts identified in this way can then be compared with other documentary sources, including newspapers and journals, to generate information on their socio-economic impacts, as well as innovative practices that communities employed to cope with and adapt to drought conditions. Ireland is fortunate in having some of the longest running newspapers in the world, some going back to the early eighteenth century, providing a rich (and often colourful – see Figure 2) source of information about the human impacts of past droughts. [13] Left: Poem describing the drought of 1806 and its impacts on flora, fauna, agriculture and water. Belfast Newsletter, 28 June 1806. Right: Guinness Press advertisement during the April 1985 Irish drought. Guinness Archive Online Collection. https://guinnessarchives.adlibsoft.com/Details/archive/110017212. Drought memories – or “we are not quite as skeptical” The light-hearted 1985 Guinness ad shown right in Figure 2 suggests that Irish people in their fifties and older are likely to have direct personal experiences and recollections of notable droughts. A key component of the Irish Droughts project is to seek out people with strong memories and systematically record their recollections of how droughts from the 1950s onward unfolded, the physical, social and economic impacts they had, and how people adjusted. In this way, our statistical and observational data are made more tangible by accounts of the real-life consequences for individuals, families and communities. This last aspect is especially important, given our goal of not only identifying past drought events in Ireland, but also gaining transferable lessons for the future. Learning for the future The nearly three decades of drought-free conditions that led to drought becoming a practically forgotten hazard in Ireland came to a crashing end in 2018. During that relatively wet period, there was little physical stimulus to prompt governments, institutions and communities to better prepare for the shifts in seasonal temperature regimes, precipitation patterns, and drought frequencies and/or severities that will likely accompany future climate change. To generate additional insights on how to build resilience to future droughts, we will look abroad to southwestern Ontario, Canada, and draw upon watershed management and drought mitigation strategies already in place there. That region’s relatively modest climate, mixed urban-agricultural land use system, established source water protection legislation, and institutional experience in managing both floods and droughts make it a useful analog for Ireland. “Rainfall warning?” The drought of summer 2018, although relatively short-lived in some areas by comparison to historical droughts, revealed the considerable vulnerabilities that exist in Ireland in the water, livestock, tillage, horticulture, and tourism sectors. Furthermore, the lack of institutional preparedness for future droughts is evidenced by the fact that the Irish national emergency management system currently has no means of categorizing drought warnings, with the 2018 event being classified simply as a rainfall warning. Through our research, we seek to enhance Irish understanding of drought risks, inform policy and practice, and ensure that rural Ireland is sufficiently prepared to deal with future climate change and its impacts on water supplies, agriculture, and the well-being of society. [1] www.ucd.ie/droughtmemories; https://twitter.com/droughtmemories

[2] Kiely, G., Leahy, P., Ludlow, F., Stefanini, B., Reilly, E., Monk, M. and Harris, J. (201) Extreme weather, climate and natural disasters in Ireland. Johnstown Castle: Environmental Protection Agency. [3] Ludlow, F., Stine, A. R., Leahy, P., Murphy, E., Mayewski, P., Taylor, D., Killen, J., Baillie, M., Hennessy, M. and Kiely, G. (2013) “Medieval Irish Chronicles Reveal Persistent Volcanic Forcing of Severe Winter Cold Events, 431-1649 CE”, Environmental Research Letters, 8 (2), L024035, doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/024035. [4] https://celt.ucc.ie/published/T100005B/text015.html [5] Baker, L., Brock, S., Cortesi, L., Eren, A., Hebdon, C., Ludlow, F., Stoike, J. and Dove, M. (2017) “Mainstreaming Morality: An Examination of Moral Ecologies as a Form of Resistance”, Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature, and Culture, 11 (1), 23-55. doi.org/10.1558/jsrnc.27506; see also Ludlow, F. and Travis, C. (2018) “STEAM Approaches to Climate Change, Extreme Weather and Social-Political Conflict”, In: de la Garza, A. & Travis, T. (eds.), The STEAM Revolution: Transdisciplinary Approaches to Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, Humanities and Mathematics. New York: Springer, 33-65. [6] Pilcher, J. R., Baillie, M. G. L., Schmidt, B. and Becker, B. (1984) “A 7,272-year tree-ring chronology for Western Europe”, Nature, 312, 150-152. [7] Cook, E. R., Seager, R., Kushnir, Y. et al. (2015) “Old World megadroughts and pluvials during the Common Era”, Science Advances 1(10) (2015), e1500561, doi:10.1126/sciadv.1500561. [8] Sigl, M., Winstrup, M., McConnell, J.R., Welten, K.C., Plunkett, G., Ludlow, F., Büntgen, U., Caffee, M., Chellman, N., Dahl-Jensen, D., Fischer, H., Kipfstuhl, S., Kostick, C., Maselli, O.J., Mekhaldi, F., Mulvaney, R., Muscheler, R., Pasteri, D.R., Pilcher, J.R., Salzer, M., Schüpbach, S., Steffensen, J.P., Vinther, B., Woodruff, T.E. (2015) “Timing and Climate Forcing of Volcanic Eruptions during the Past 2,500 Years”, Nature, 523, pp.543–549. [9] Rao, M. P. et al. (2017) “European and Mediterranean hydroclimate responses to tropical volcanic forcing over the last millennium,” Geophysical Research Letters, 44, 55894. [10] Human and natural archives have their own biases, sensitivities, strengths and weaknesses and must each be “read” with these in mind. Where the Irish oaks are not especially forthcoming about the climatic impacts of the great 536 eruption, the sample in Figure 1 being an exception, the Irish Annals suggest its severity for Ireland in reporting the “failure of bread” for 538 (when applying the essential chronological corrections of McCarthy. D. (2008) The Irish Annals: Their Genesis, Evolution and History. Dublin: Four Courts Press), despite their vestigial character at this early date. The landmark 2015 tree-ring-based reconstruction of the Palmer Drought Severity Index for the Common Era is also tested for accuracy against historically documented periods of extreme wet and drought (Cook, E. R. et al. (2015) “Old World megadroughts and pluvials”). [11] Murphy, C., et al. (2018) “A 305-year continuous monthly rainfall series for the island of Ireland (1711-2016)”, Climate of the Past, 14(3), 413-440. [12] Noone, S., Broderick, C., Duffy, C., Matthews, T., Wilby, R.L. and Murphy, C. (2017) “A 250‐year drought catalogue for the island of Ireland (1765–2015)”, International Journal of Climatology, 37, 239-254. [13] Murphy, C. et al. (2017) “Irish droughts in newspaper archives: Rediscovering forgotten hazards?” Weather, 72(6), 151-155.

62 Comments

|

Archives

August 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

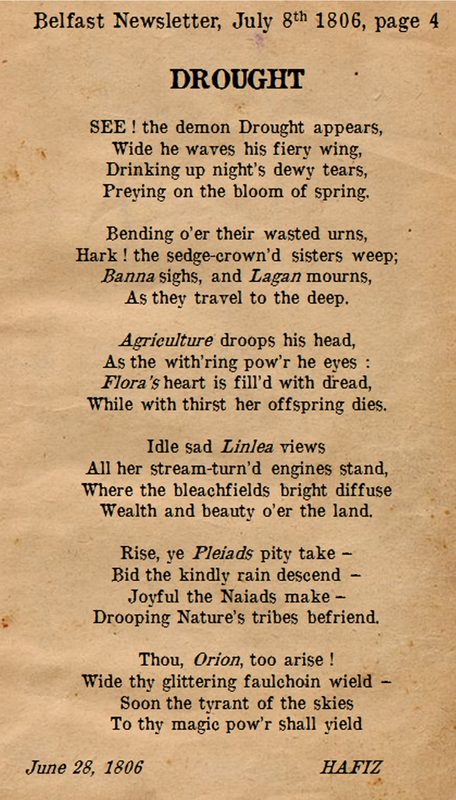

RSS Feed