|

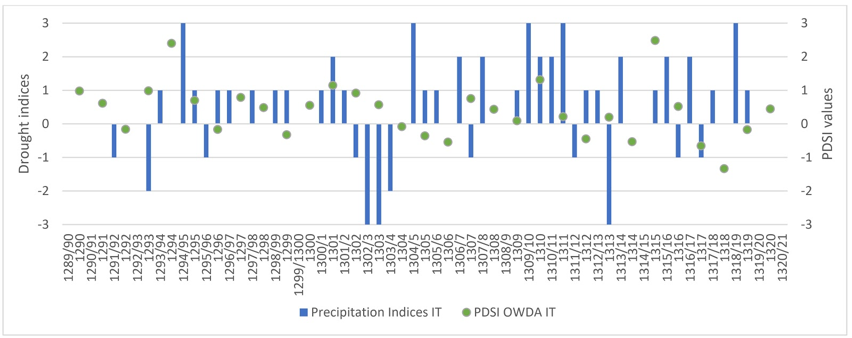

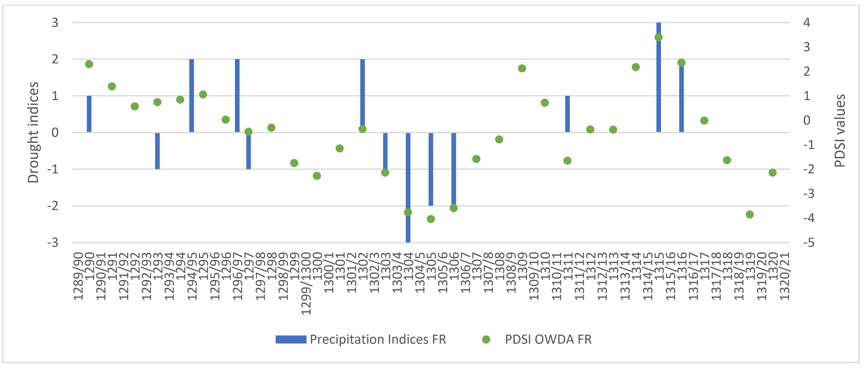

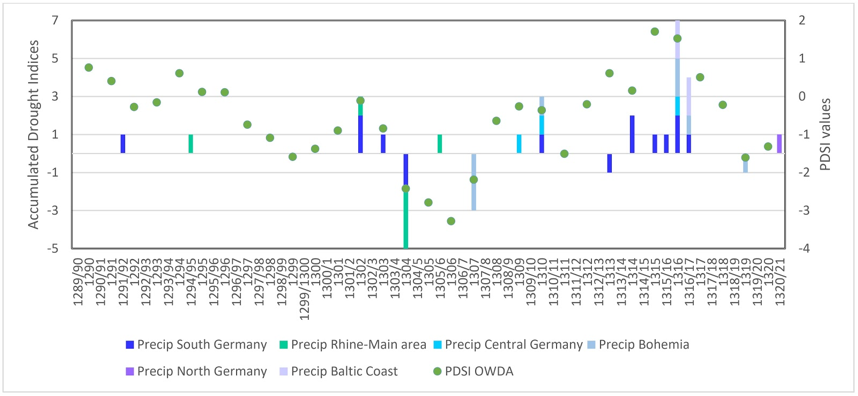

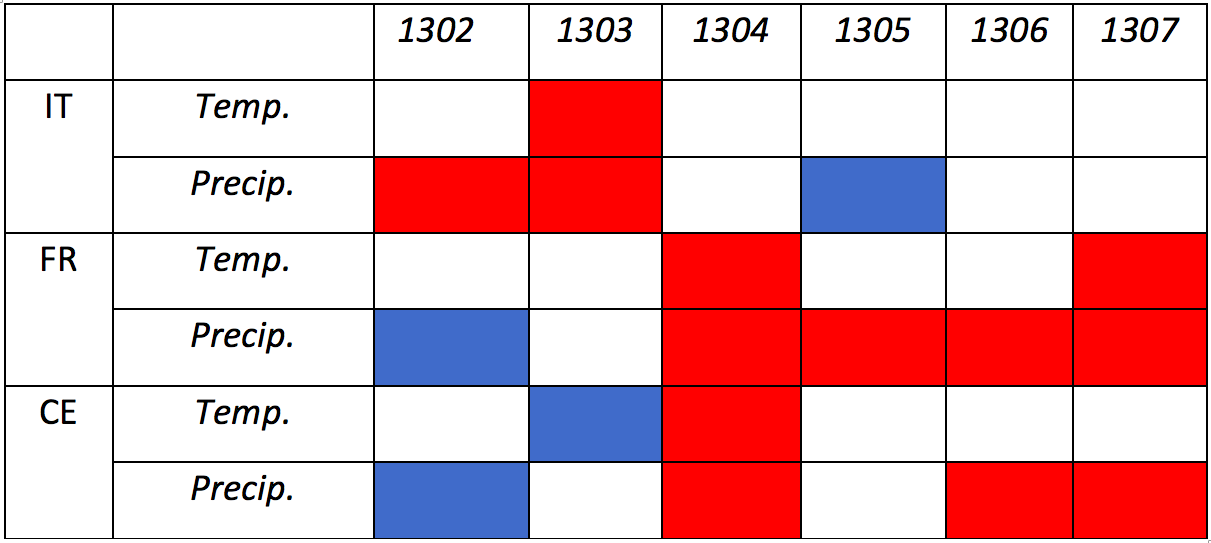

Martin Bauch, Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe (GWZO), Leipzig Thomas Labbé, Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe (GWZO), Leipzig, Maison des Sciences de l’Homme de Dijon, Dijon Annabell Engel, Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe (GWZO), Leipzig Patric Seifert, Leibniz Institute for Tropospheric Research (TROPOS), Leipzig Recently coined the “1310s event” (Slavin 2018), the wet anomaly of the 1310s has attracted a lot of attention from scholars, who commonly interpret it as a signal of the transition between the warmer Medieval Climate Anomaly to the chilly Little Ice Age in Europe (Campbell 2016). Despite the fact that current worries about global warming have led scholars of premodern climate history to pay increasing attention to drought events (Wetter et al. 2014; Brázdil et al. 2019; Brázdil et al. 2018; on the Middle Ages, Rohr et al. 2018), the subject remains in its infancy. Focusing on dry anomalies in the early fourteenth century, a distinctive “1300s event” set in opposition to the wet 1310s is detectable. It is therefore time to examine this meteorological anomaly, and we have recently done so, aiming to understand its meteorological, economic and social features (Bauch et al., 2020). Our study proposes a reconstruction of the drought-period for three different regions: central and northern Italy, eastern France, and central Europe, and strives to identify the underlying meteorological pattern. It then highlights the diverse socio-economic impacts of this event on medieval societies. Reconstructing the Drought of 1302–1307 The reconstruction of semi-annual precipitation indices on the basis of narrative sources (Fig. 1, for methodology, see Bauch et al. 2020) suggests a sustained dry period in Italy that lasted nearly two years, from the growing season of 1302 until the non-growing season of 1303/4. The precipitation indices for France are generally quite scarce, and yet they show a pronounced drought pattern in the growing seasons of 1304-1306. In central Europe, the indices show drought in the growing seasons of 1304 and 1307, whereas data from written sources for the seasons in between, which according to the Old World Drought Atlas (OWDA) were especially dry, is practically non-existent. While our reconstructions generally correspond quite well with the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) taken from the OWDA (Fig. 1), the congruence is less convincing in the case of Italy, where only a handful of dendrochronological series from the Alps and Calabria are available. These discrepancies show that a validation and refinement of climate reconstruction derived from proxy data by means of careful critical analysis of written historical sources is worthwhile, especially concerning the chronology of extreme events. Underlying Meteorological Patterns In fact, narrative sources give access to a more detailed picture of the meteorological conditions prevailing in Europe between 1302 and 1307, including a remarkable feature evident in Figure 2. Our analysis of written documentation (chronicles, charters, roll accounts) reveals inverse trends in southern Europe (Italy) and Europe north of the Alps (France and central Europe). While Italy witnessed two successive dry summers in 1302 and 1303, France and central Europe experienced wet, cold conditions that even led to floods in the summer of 1302. On the other hand, these regions to the north witnessed very dry and hot anomalies from 1304 to 1307, while conditions south of the Alps in Italy were normal in 1304, 1306, and 1307, or even abnormally rainy in the summer of 1305. The documentary data indeed suggest the occurrence of an alternating large-scale weather pattern over large parts of Europe between 1300 and 1310: a water (or more precisely: precipitation) seesaw, as it was recently discussed by Toreti et al. (2019) concerning the drought events of 2018 and others of the last 500 years. This phenomenon describes a remarkable dipole of negative precipitation anomalies over one part of Europe and positive ones over another part of the continent. The 2018 drought has been associated with pronounced positive anomalies in the geopotential height of the 500-hPa level of atmospheric pressure over the continental European landmass north of the Alps. This blocking situation led to the formation of low-pressure anomalies over both northern and southern Europe, with resulting precipitation patterns such that central Europe suffered a severe lack of precipitation whereas northern and southern Europe experienced an excess of precipitation. Thus, in the 2018 case, the water seesaw was positive over southern Europe and negative over central Europe. Similar to what was reported by Toreti et al. (2019), the predominant weather patterns found for the period from 1302 to 1307 must have likewise originated from certain seesaw constellations and associated patterns in the geopotential height fields. Because such droughts spanning multiple seasons and several regions did not occur during the thirteenth century and did not occur again during the fourteenth until 1360–1362, it is possible to interpret these uncommon conditions, combined with the 1310s wet anomaly, as part of the climatic transition from the MCA to the LIA. The dry anomaly characterizing the “1300s event” can be seen as the starting point of the LIA and the changing meteorological patterns of this period. Impact / Responses to Drought and Water Scarcity It is often presumed that periods of drought were unproblematic or even beneficial for the subsistence of western Europeans in the Middle Ages. While it is true that cereals and wine harvests were not heavily endangered by droughts, other difficulties did arise in such periods, especially problems of access to water. In 1303, for example, the city of Parma had to dig a new well, larger and deeper than before (Bonazzi, 1902, 86). The Tuscan city of Siena, situated far from any larger bodies of water, took similar measures: city councilors authorized digging in a local church in an attempt to find a mythological underground waterway, the so-called Diana, in April 1305, one year after the end of the drought (Bargagli Petrucci, 1903, II, 20). In addition, water shortages were often associated with the spread of contagious diseases via contaminated water sources (Pribyl 2017), as happened in Paris in 1307 (Buchon, 1827). Another side effect of prolonged major droughts in the fourteenth century was the temporary disruption of production—and sometimes even of communication routes—that relied on rivers. The lack of water power made it difficult to mill grain into flour and to transport foodstuffs from the regions of production to city markets. These challenges could have economic consequences, as it was the case in Alsace in 1304 and 1305, where although the grain and wine harvests were plentiful in these years, the prices of bread and wine actually went up (Jaffe, 1861). Finally, a higher risk of city fires was certainly the most dangerous consequence of long-lasting droughts. A peak in urban fires during the 1302–1305 drought is visible, for example, in Italy, as well as in France in 1306. Altogether, the consequences of the 1302–1307 dry period were certainly not negligible across Europe. A detailed analysis comparable to that conducted on the 1540 mega-drought (Wetter et al. 2014) is evidently not possible due to the lack of sources, but the “1300s event” certainly holds more questions to be answered and deserves more attention among historians of climate, due both to the pronounced climatological patterns and its probable significant social impact on European societies in the decades preceding the Black Death. References: Bargagli-Petrucci, F., Le Fonti di Siena e il loro acquedotti. Note storiche dalle origini fino al MDLV, Vol. II, Documenti, Siena, Leo S. Olschki, 1906.

Bauch, M., Labbé, T., Engel, A., and Seifert, P., “A Prequel to the Dantean Anomaly: The Water Seesaw and Droughts of 1302–1307 in Europe,” Clim. Past Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-2020-34, forthcoming, 2020. Bonazzi, G. (ed.), Chronicon Parmense. Ab Anno MXXXVIII usque ad Annum MCCCXXXVIII., Rerum Italicarum Scriptores (RIS²), 9/9, Città di Castello, Lapi, 1902. Brázdil, R., Kiss, A., Luterbacher, J., Nash, D. J., Řezníčková, L., “Documentary Data and the Study of Past Droughts: A Global State of the Art,” Clim. Past, 14, 2018, p. 1915–1960, doi.org/10.5194/cp-14-1915-. Brázdil, R., Kiss, A., Řezníčková, L., Barriendos, M., “Droughts in Historical Times in Europe, as Derived from Documentary Evidence,” Herget, J. and Fontana, A. (eds), Paleaohydrology: Traces, Tracks and Trails of Extreme Events, Cham, Springer, 2019, p. 65–96. Buchon, J. A. (ed.), Chronique métrique de Godefroy de Paris, suivie de la taille de Paris en 1313, Collection des chroniques nationales françaises, 9, Paris, Verdière, 1827, p. 1–304. Campbell, B., The Great Transition: Climate, Disease and Society in the Late-Medieval World, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2016. Jaffé, P. (ed.), “Annales Colmarienses maiores a. 1277-1472,” Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores, 17, Hannover, 1861, p. 202–232. Pribyl, K., Farming, Famine and Plague: The Impact of Climate in Late Medieval England, Cham, Springer, 2017. Rohr, C., Camenisch, C., and Pribyl, K., “European Middle Ages,” in White, S., Pfister, C., and Mauelshagen, F. (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Climate History, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, p. 247–263. Slavin, Ph., “The 1310s event,” in White, S., Pfister, C., and Mauelshagen, F. (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook for Climate History, London, Palgrave McMillan, 2018, p. 495–515. Toreti, A., Belward, A., Perez‐Dominguez, I., Naumann, G., Luterbacher, J., Cronie, O., Seguini, L., Manfron, G., Lopez‐Lozano, R., Baruth, B., Berg, M., Dentener, F., Ceglar, A., Chatzopoulos, T., and Zampieri, M., “The Exceptional 2018 European Water Seesaw Calls for Action on Adaptation,” Earth's Future, 7, 2019, p. 652–663, doi:10.1029/2019EF001170. Wetter, O., Pfister, C., Werner, J.P., Zorita, E., Wagner, S., Seneviratne, S.I., Herget, J., Grünewald, U., Luterbacher, J., Alcoforado, M.J., Barriendos, M., Bieber, U., Brázdil, R., Burmeister, K.H., Camenisch, C., Contino, A., Dobrovolný, P., Glaser, R., Himmelsbach, I., Kiss, A., Kotyza, O., Labbé, T., Limanówka, D., Litzenburger, L., Nordli, Ø., Pribyl, K., Retsö, D., Riemann, D., Rohr, C., Siegfried, W., Söderberg, J., Spring, J.L., “The year-long unprecedented European heat and drought of 1540 – a worst case,” Clim Chang., 125, 2014, p. 349–363, doi:10.1007/s10584-014-1184-2.

42 Comments

|

Archives

August 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed