|

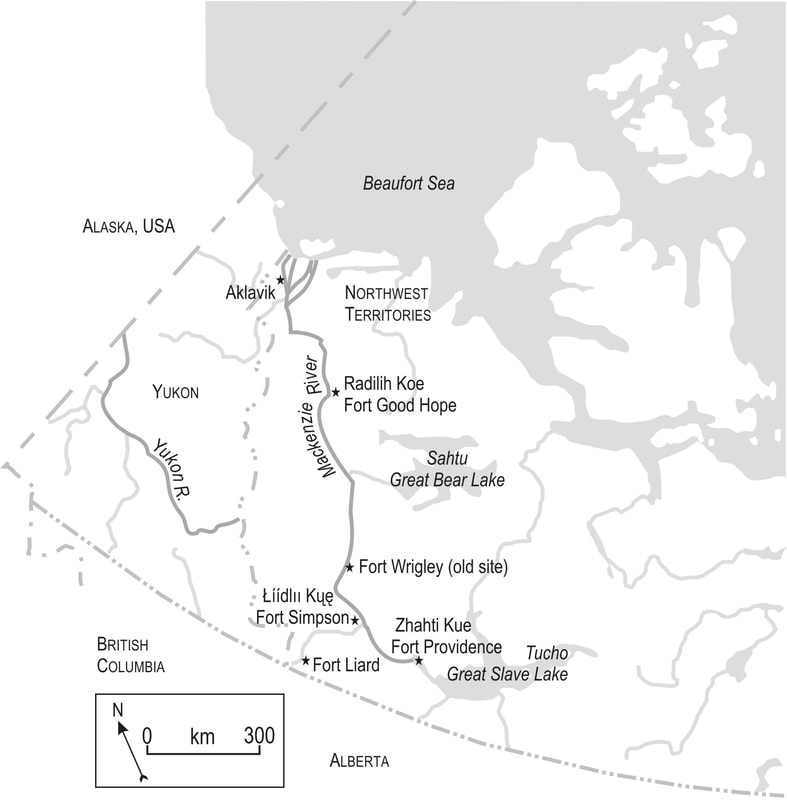

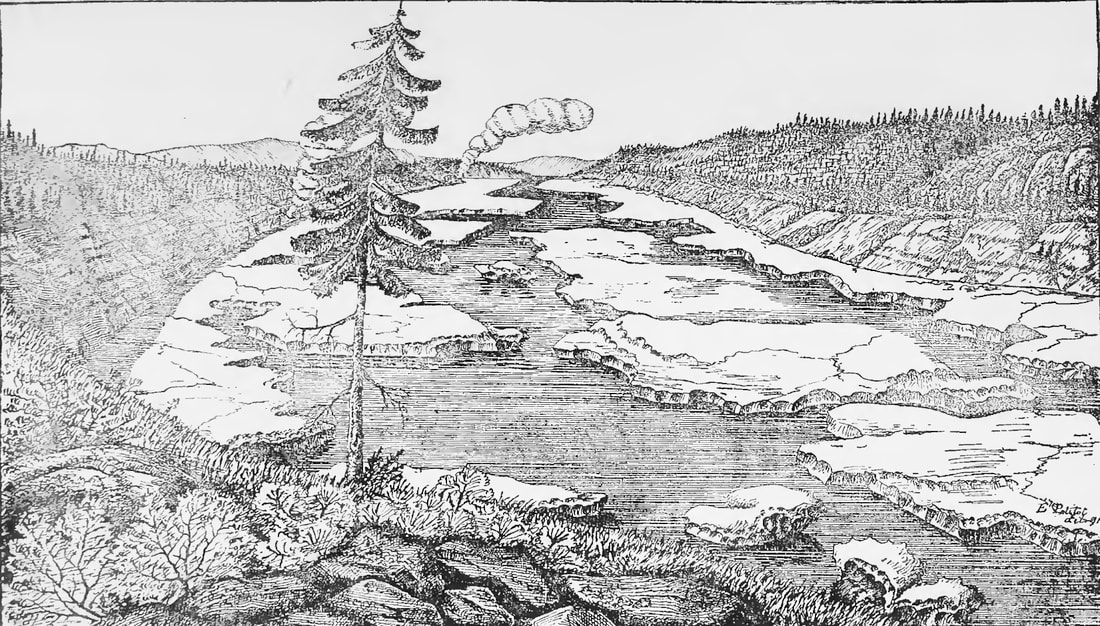

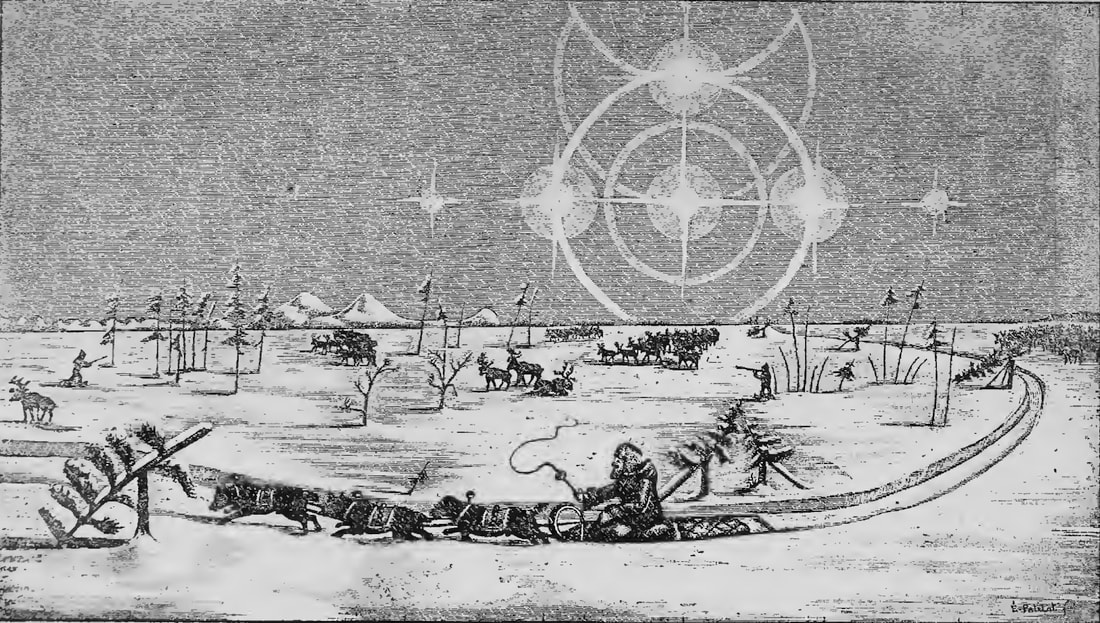

Liza Piper, University of Alberta Times of hunger and starvation were part of life for northern Indigenous peoples. Dene, Inuvialuit, and Gwich’in shared lessons about planning to avoid starvation, the need to show proper respect and gratitude for good hunts and successful fishing, and how to eat after a period of hunger.[1] These ancient stories were essential education for subsistence that relied on migratory creatures (caribou, birds), animals that experienced cyclical population crashes (lynx, marten, Arctic hare), and others sensitive to weather and water conditions (beaver, muskrat). It took great skill and expertise, rooted in generations of experience on the land—knowledge in place in deep time—as well as some luck, to live off and with the land along the Mackenzie and Yukon rivers in the nineteenth century. In the late 1880s, fortune failed and starvation came. The winter of 1887-88 was exceptionally cold: Hunters who traded at forts Providence and Liard in the Mackenzie district found beavers dead in their lodges. In these regions, beavers survived long winters by building up fat in their tails before the onset of cold and then eating saplings they stored below the ice. In a long winter, with deep freezes, beavers starved.[2] Fur returns were poor that year, made worse by scarce marten. There were also ominous reports that there were no “rabbits” (mostly snared for food) to be found.[3] The cyclical crashing of hare populations, followed by the abrupt declines in their predators—marten, lynx, and sometimes foxes—was underway. Early in the winter there had been some hunger but thankfully the snow was deep and the moose numerous; with successful hunts, hunger soon abated. If the winter of 1887-88 was exceptionally cold, the next year was even worse: “the hardest winter in 30 years” according to the Hudson’s Bay Company district chief Julian Camsell.[4] The temperature record preserved at Fort Good Hope shows that it was not extreme cold that made the winter so bad, but rather the dramatic fluctuations in temperature, followed by a deep-freeze in February. The bad weather had started with a “summer of rain” as Oblate missionary Jean Séguin wrote from Fort Good Hope.[5] The winter saw “frequent thaws and very little snow,” which made it impossible to hunt larger game animals -- caribou and moose.[6] The climatic conditions were then joined to the cyclical collapse of marten, rabbit, and lynx populations and the absence of caribou from some of their normal routes.[7] In the winter of 1888-89, people across the Mackenzie district had to rely on fisheries and provisions (mostly dried fish, but also dried meat and flour). Fort Simpson sent ten sled loads of provisions to nearby Fort Wrigley. After January the Company's servants at Simpson were “reduced ...to eat the furs in store.”[8] By spring the stores were empty. In reports to his superior, Camsell detailed “the privations and hardships experienced …during the past winter,” which saw forty-seven deaths across the district attributed to starvation.[9] This was by far the greatest mortality from that cause in any year in the late nineteenth or twentieth centuries. Climate and climate history are foundational to the colonial histories of the lands along the Mackenzie and Yukon rivers. Nineteenth-century climate discourses shaped perceptions of the desirability of northern environments for colonization. Twentieth-century climate discourses shaped the willingness of Canadian governments to provide in situ health care, rather than relocating sick northerners to southern institutions. Climate governed the possibility to extend the temperate agricultural systems that were integral to settler colonialism elsewhere in Canada. The limitations of agriculture along the Mackenzie and Yukon rivers profoundly shaped the character of northern colonialism, not least by feeding an intense anxiety among colonizers as to their own prospects for good health and survival in northern places. The trade networks that flourished early on and served as a foundation for colonial relations, adapted to the annual break-up and freeze-up of waterways – the opening and closing of the region to the south. This created rhythms in the long-distance movement of people, goods, and pathogens that endured into the 1950s. And, through all of this, technologies for meteorological investigation accompanied explorers, scientists, missionaries and traders. The North was essential to the network of national (and international) meteorological observatories erected from the mid-nineteenth century onward, used to acclimatize colonizers to the ‘new worlds’ they sought to claim. The network of instrumental temperature observations (that dates back to the 1880s) also facilitates historical research into the role of weather, climate, and climate changes in shaping good and ill-health during this period of colonisation. It shows, for instance, that while the winter of 1887-88 was exceptionally cold, it was the temperature fluctuations the following year, alongside independent variation in animal populations, that made for Camsell’s “hardest winter.” There is nothing simple or straightforward, that is, about weather or climate descriptions in this period. Just as Mary Black Rogers’ classic essay on ‘starvation’ demonstrated the instability of this word and its many meanings in the fur trade, so too “extreme cold” and “harsh winter” have to be situated in their colonial context in order to be understood.[10] Exceptional weather brought dire hunger in the winter of 1888-89 and with it the first prolonged discussion among missionaries, traders, government agents about their responsibility to help northern peoples – on lands at the time not ceded by treaty – in a moment of great need.[11] Northern peoples stayed away from the trade posts (where there were fewer prospects for subsistence than on the land), broke up into smaller groups, and shared what they had. Officials with the Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) saw themselves as benevolent and did not want to be tarred with the same brush that condemned British colonial officials for their role in the Great Famine that led to over 5 million deaths in India.[12] But the criteria that governed how much relief to provide was how much the DIA was willing to pay, not how much was needed to sustain life in a period of great hardship. The perception of the north as an intrinsically unhealthy place, rooted in intersecting discourses of climate, health, and “race” in the late nineteenth century, reinforced the notion that providing relief to northern peoples was an expense that needed to be contained. The experiences of the winter of 1888-89 resituate a well-known theme about historical struggles for subsistence in subarctic and arctic places within the context of colonialism. This episode appears in a larger book project examining the intersection of health and environmental change as part of the process of settler colonialism along the Mackenzie and Yukon rivers (today’s Yukon and Northwest Territories) between 1860 and 1940. To read more of the findings to date from this project, please see the following publications:

Acknowledgement I wish to gratefully acknowledge the Inuvialuit Cultural Centre, the Gwich’in Tribal Council Department of Cultural Heritage, and the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Heritage Department for granting access to unpublished interview transcripts with elders as part of the research for the larger project discussed here. [1] George Blondin, When the World Was New: Stories of the Sahtu Dene (Yellowknife: Outcrop, 1990), 40; Charles Arnold, Wendy Stephenson, Bob Simpson, and Zoe Ho, eds. Taimani: At That Time, 3rd ed. (Inuvialuit Regional Corporation, 2011), 18.

[2] Michael Aleksiuk, “The Seasonal Food Regime of Arctic Beavers,” Ecology 51, no. 2 (Mar. 1970): 267. [3] Post Report dated Fort Smith, August 30, 1888, B. 200 /e/17, Hudson’s Bay Company Archives. [4] J.S. Camsell to Joseph Wrigley, Fort Smith, Sept. 10, 1889, B. 200/b/39, vol. 3, HBCA. [5] J. Séguin to his sister, 18 février 1889, acc# 71.220, file 7346, Provincial Archives of Alberta. [6] Camsell to Wrigley, Sept. 10, 1889. [7] Richard Hardisty, Inspection Report Mackenzie River District, Summer 1889, B.200/e/18, HBCA. [8] Extract from the Commissioner’s Letter to the Secretary, 30 Sept. 1889, RG 10, Vol 3708, File 19,502, Parts, 1,2,3 Reel C-10124, Library and Archives Canada. [9] Camsell to Wrigley, Sept. 10, 1889. The number of deaths is tallied from Oblate, HBC, and government records. [10] Mary Black-Rogers, “Varieties of ‘Starving’: Semantics and Survival in the Subarctic Fur Trade, 1750-1850,” Ethnohistory, 33, no. 4 (1986): 353-383. [11] See correspondence in RG 10, Vol 3708, File 19,502, Parts, 1,2,3 Reel C-10124, Library and Archives Canada. [12] Mike Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World (London: Verso, 2001).

3 Comments

|

Archives

August 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed