|

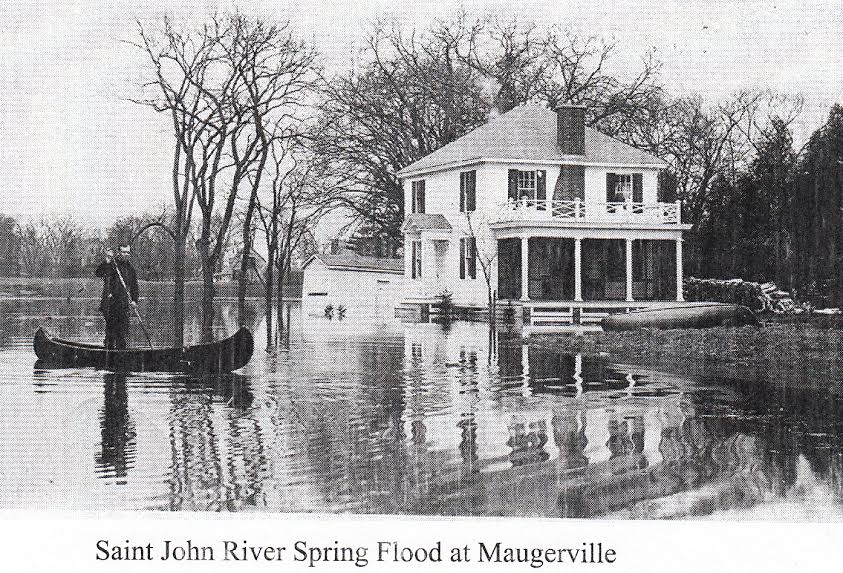

For all but a sliver of our existence, people everywhere have been “living weather”: dependent upon local ecologies for the fuel, nutrition, and other materials to sustain them through their exposure to the elements in the course of the seasons. I study evidence of this in the diaries of British emigrants and American Loyalists dwelling in the British North American colonies of Nova Scotia, St. John’s Island, or Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland. Diarists learned to ‘live weather’ – learned local weather ecology - through a praxis of observation.

This praxis involved continuously integrating traditional ecological knowledge from emigrant’s former home places, with experiential knowledge developed through observation of the effects of weather on the land and waterscapes of their new homes. Settlers engaged in a praxis of observation through interaction with local human and ecological communities. Thus far, I have focused on risk and vulnerability, and experimentation and adaptation, as key themes within this praxis. I am interested in the multiple ways that settlers learned local weather ecology, and in the course of adapting to it, were keenly attuned to extremes, and changes over time. This work is part of a larger project of reconstructing climate and climate-society relationships in the region between 1780 and 1920. Teresa Devor is a PhD candidate in environmental history at the University of New Brunswick. Click here to read some of Teresa's online articles.

15 Comments

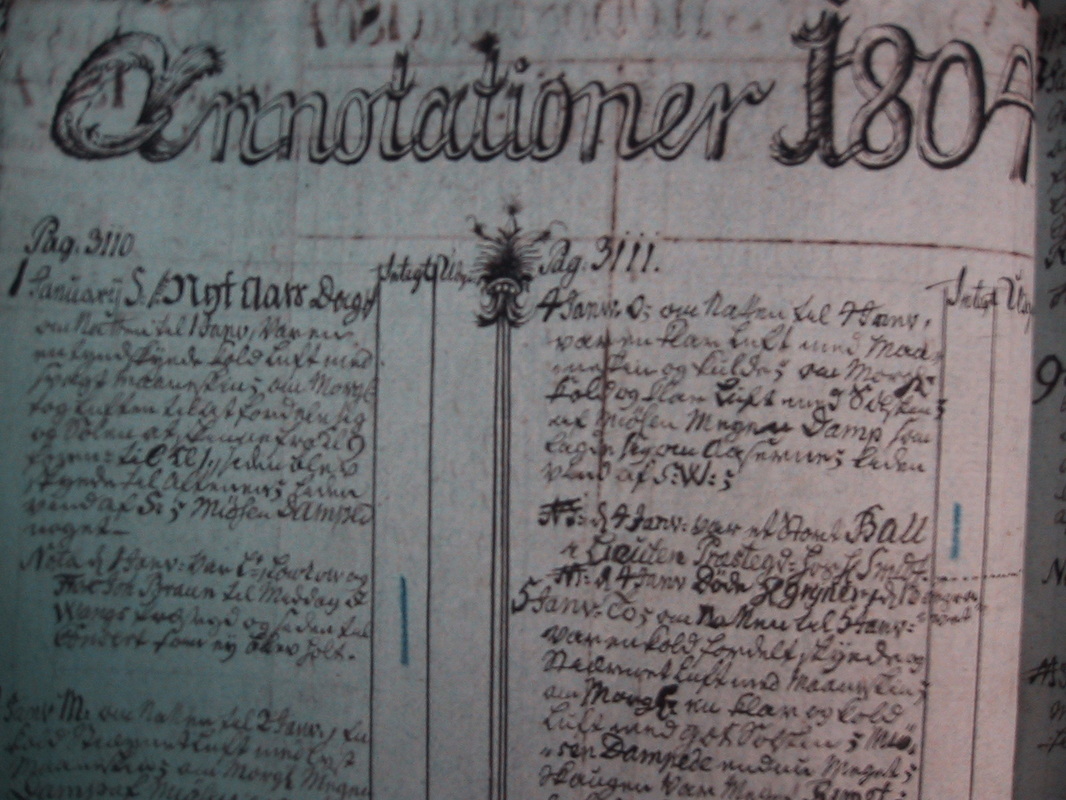

I discovered a farm's diary when I began my master's thesis in historical climatology. After a tip about a historic source - a farm diary that existed in Hamar, Hedmark County in eastern Norway - I could start my thesis. These diaries contained weather and climate information far back in time (around 1750 AD). This was unique for Norway, since we were a peasant country, and few in Norway could write at that time.

Early modern climatic cooling coincided with the European age of exploration, and it was in the Arctic that the interactions between these human and environmental movements found their fullest expression. This project will develop an environmental history that explains how Europeans were able to explore and exploit the Arctic in unprecedented ways during a climate that should have discouraged those activities. It will be the first comprehensive study to link climate change to the human history of the seventeenth-century Arctic.

Using a wide range of interdisciplinary sources and techniques, in the first phase of this project I will reconstruct the history of the early modern Arctic climate with unprecedented precision, linking fluctuations in average temperature to shifts in the distribution of sea ice, regional wind patterns, and ocean currents. In the second phase, I will investigate how environmental changes influenced, and were influenced by, the increasingly lucrative penetration of the Arctic by European explorers and entrepreneurs. I will unravel relationships between climate change and Arctic journeys of exploration, whaling, military competition, and the fur trade. Finally, I will examine how their experiences in the north may have stimulated new understandings of climate change on both shores of the Atlantic. The completed project will help inform present and future attempts at adaptation in the face of northern climate change. Dagomar Degroot is an assistant professor of environmental history at Georgetown University. He directs HistoricalClimatology.com and the Climate History Network. My dissertation is a historical examination of the marine and terrestrial space of the Bering Straits, a region united by ecology but divided, in the 20th century, by politics and ideology. From the 1850s through the last years of the Soviet Union, my research compares how communist and capitalist development impacted, and was impacted by, the region’s challenging ecology. I examine how modern states – which depend upon energy-intensive industry and agricultural production – function in a place with little solar gain or fossil fuel. Additionally, I explore the assumptions and impacts of communism and capitalism, ideologies that hinged on industrial development. As a result, both used energy intensively and reshaped local environments at a large scale. The U.S. and U.S.S.R. were major contributors to what some geologists term the Anthropocene, an era of profound, human-driven change, and a new field of research across disciplines. My project is a history of the arrival of the Anthropocene in the far north.

This project explores how global commodities influenced modern agriculture and land use in Canada and the U.S. It focuses on Canada’s “other oil,” triglycerides, and how the development of new consumer goods created a global oilseed industry, first in flax and cottonseed, but later in soybeans, sunflower, corn, and Canola. The role of the European wheat market is well known in Prairie historiography, but the rapidly growing chemical sector also helped shape the Plains during the Second Industrial Revolution. Flax and firewood may seem like obscure topics, but I argue that small shifts in the consumption of ordinary commodities had major ripple effects across North American landscapes.

The Great Plains Population and Environment Project has been using historical climate data for their US research for almost two decades, and we will be using similar methods in the Canadian case studies. Second, I'm working on a specific paper this Fall that examines an early form of "precision agriculture" in the West -- the collection of massive amounts of weather and crop data by agricultural corporations. Third, I'm just generally interested in how farmers understood and gauged weather patterns over time. Dr. Josh MacFadyen is a postdoctoral fellow in environmental history at the University of Saskatoon. Dagomar Degroot, The Frigid Golden Age: Experiencing Climate Change in the Dutch Republic, 1565-17203/1/2015 The Frigid Golden Age is a manuscript that furnishes the first detailed analysis of how climate change influenced the so-called “Golden Age” of the Dutch Republic. It explores the nadir of a “Little Ice Age” between 1565 and 1720, when European temperatures declined by nearly one degree Celsius, relative to their twentieth-century averages. By shortening the growing season and altering animal ranges, cooler temperatures contributed to famine and social unrest in the agricultural economies that dominated Europe.

However, a changing climate also offered opportunities that were aggressively exploited by citizens of the urban, capitalist Dutch Republic, which emerged as a great power during the coldest decades of the Little Ice Age. The Frigid Golden Age demonstrates that the dynamic society of the Dutch Republic was more resilient in the face of climate change than its European neighbours. The book therefore challenges recent histories that ignore the Dutch Golden Age to present straightforward connections between climate change and early modern crises. The Frigid Golden Age contributes not only to debates in early modern historiography, but also, vitally, to present-day discussions of global warming. Dagomar Degroot is an incoming assistant professor of environmental history at Georgetown University. He directs HistoricalClimatology.com and the Climate History Network. |

Archives

August 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed