A Millennium of Climate Change in Europe: From Medieval Warming to Today's Climate Crisis12/19/2021  In the 22nd episode of Climate History, co-hosts Emma Moesswilde and Dagomar Degroot interview Christian Pfister, co-author (with Heinz Wanner) of a new book: Climate and Society in Europe: The Last Thousand Years. Pfister is one of the founders of the related fields of climate history and historical climatology. He explains how he helped establish these fields, how they benefit from genuine collaboration between disciplines, and what they may be revealing about today's climate crisis. He also describes the most important themes in the last millennium of climate change in Europe - and why it is so important that scholars introduce their methods, models, and sources to a broad audience. To listen to this episode, click here to subscribe to our podcast on iTunes. If you don't have iTunes, you can still listen by following us on SoundCloud or Spotify.

165 Comments

In the 21st episode of Climate History, co-host Emma Moesswilde interviews Debjani Bhattacharyya, Associate Professor of History at Drexel University. Professor Bhattacharyya is among the most innovative scholars of past climate change, and the histories she uncovers have clear relevance for the future of the Indian Ocean World.

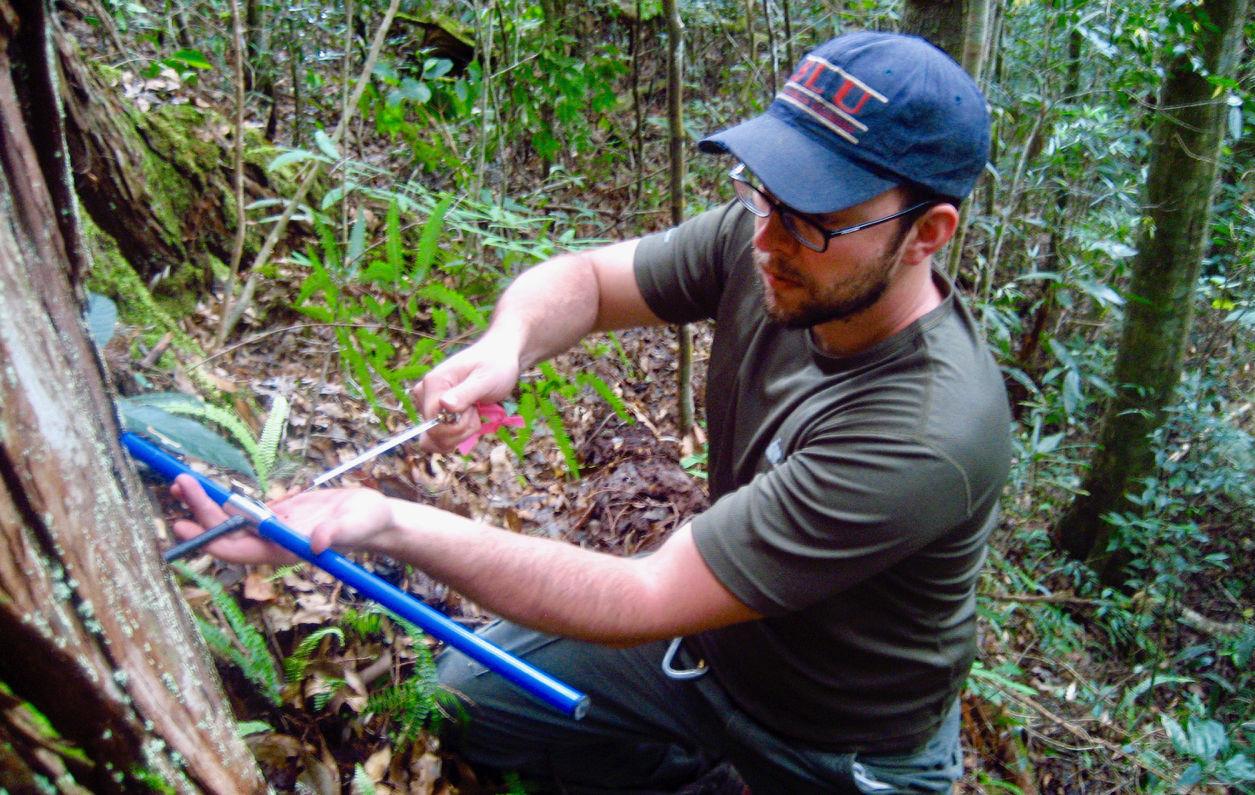

Moesswilde and Bhattacharyya discuss the history of human responses to climate change at sea; the role of environmental disasters in shape urban trajectories; the role of insurance markets in creating weather knowledge; and how transdisciplinary perspectives on the past can inform our understanding of a hotter future. To listen to this episode, click here to subscribe to our podcast on iTunes. If you don't have iTunes, you can still listen by following us on SoundCloud or Spotify.  In the 14th episode of Climate History, co-hosts Dagomar Degroot and Emma Moesswilde interview Joseph Manning, the William K. and Marilyn Milton Simpson Professor of Classics at Yale University. Professor Manning is a leading expert on the law, politics, and economy of the ancient world, particularly the Hellenistic Period (between 330 and 30 BCE). In recent years, he's led efforts to uncover a link between volcanic eruptions, climatic shocks, and rebellions in ancient Egypt: efforts that inspired headlines in the Washington Post, the New York Times, and elsewhere. Professor Manning explains how his team uncovered the influence of climate change in Egyptian history, and what the ancient world has to tell us about our uncertain future. A Conversation with Amy Hessl and Valerie Trouet: What Tree Rings Reveal about Climate Change3/4/2020 In the 12th episode of Climate History, co-hosts Dagomar Degroot and Emma Moesswilde interview Amy Hessl of West Virginia University and Valerie Trouet of the Laboratory of Tree Ring Research at the University of Arizona. Hessl and Trouet are two of the world's leading paleoclimatologists. They scour the Earth to measure the growth rings in trees, which they use to uncover ancient climate changes that likely influenced the fate of past societies. Among other work, they have led groundbreaking studies that identified ancient changes in atmospheric circulation, hurricane frequency, the prevalence of wildfires, and even the precipitation patterns that may have set the stage for the expansion of the Mongol Empire. In this interview, we discuss the nature of tree ring research, the challenge of communicating its insights to the public, and Professor Trouet's groundbreaking new book, Tree Story: The History of the World Written in Rings.

To listen to this episode, click here to subscribe to our podcast on iTunes. If you don't have iTunes, you can still listen by clicking here.  In the tenth episode of Climate History, our podcast, Emma Moesswilde and Dagomar Degroot interview Bathsheba Demuth, assistant professor of environmental history at Brown University. Professor Demuth specializes in the lands and seas of the Russian and North American Arctic. Her interests in northern environments and cultures began when she was 18 and moved to the village of Old Crow in the Yukon, where she spent several years training sled dogs. In the years since, she has visited and lived in Arctic communities across Eurasia and North America. She has a BA and MA from Brown University, and an MA and PhD from the University of California, Berkeley. Her writing has appeared in publications from the American Historical Review to the New Yorker. Her first book, Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait is now out with Norton, and has received rave reviews in both popular and academic publications. Professor Demuth is a returning guest. In our first interview, she introduced the major themes of what was then her doctoral dissertation, and is now Floating Coast. In this episode, she describes how she wrote the book, and what we can learn from it. She details her experiences in the Arctic, her deep engagement with the community of Old Crow, her thinking about non-human actors in historical stories, her success in writing for the general public, and her views on what the past can reveal about the future of the rapidly-warming Arctic. To listen to this episode, click here to subscribe to our podcast on iTunes. If you don't have iTunes, you can still listen by clicking here. In the ninth episode of Climate History, our podcast, we relaunch with a new co-host: Emma Moesswilde, PhD Student in Environmental History at Georgetown University. For the relaunch, Moesswilde and Dagomar Degroot are joined by Kevin Anchukaitis, associate professor of geography at the University of Arizona and one of the world's leading paleoclimatologists. Anchukaitis uncovers and interprets climate changes over the past two thousand years. He’s currently active in projects that identify past climatic trends in nearly every part of the Earth. He uses many techniques to reconstruct those trends, including dendroclimatology; climate field reconstruction and spatiotemporal data analysis; stable isotope analysis; proxy systems modeling, and the integration of paleoclimate data with General Circulation Modeling.

In this episode, Moesswilde, Degroot, and Anchukaitis discuss how and why Earth's climate has changed over the past two thousand years; how scholars "reconstruct" those changes; how historians can link the changes to the course of human history; why this research matters today; and how to communicate scholarship on past climates to the widest possible audience. To listen to this episode, click here to subscribe to our podcast on iTunes. If you don't have iTunes, you can still listen by clicking here. A Conversation with Dr. Dagomar Degroot: Societal Resilience and Adaptation in the Little Ice Age6/15/2018  In the eighth episode of the Climate History Podcast, PhD candidate Robynne Mellor (Georgetown University) interviews Dr. Dagomar Degroot, director of HistoricalClimatology.com, about his new book: The Frigid Golden Age: Climate Change, the Little Ice Age, and the Dutch Republic, 1560-1720. Dr. Degroot is an assistant professor of environmental history at Georgetown University, where his research focuses on societal resilience and adaptation to abrupt climate change; conflict and climatic trends, particularly in the pre-industrial Arctic; and the environmental history of outer space. His next book, Civilization and the Cosmos, under contract with Harvard University Press and Viking UK (a division of Penguin Random House), will trace how dramatic environmental changes across the solar system influenced human history. At Georgetown, he teaches courses on a range of interdisciplinary topics, from the history of Mars in science and culture to the present-day Anthropocene. He is also the co-director of the Climate History Network, the director of the Climate Tipping Points Project, and the usual host of the Climate History Podcast.  In this episode, Mellor and Degroot discuss how the Dutch thrived in the Little Ice Age; the limitations of histories that focus exclusively on disaster stories; the challenges of interdisciplinary work; the keys to getting a job in environmental history; and the culture shock of moving from Canadian to American academia. To listen to this episode, click here to subscribe to our podcast on iTunes. If you don't have iTunes, you can still listen by clicking here. Climate change might be the most important issue the world faces today. Readers of this site will know it has a rich history. It helped trigger the evolution of sentience in primates, created conditions that encouraged agriculture, and influenced the rise and fall of civilizations from Bronze Age Greece to the Ottoman Empire. Its present, as we have recently been reminded, affects us all. In just the last week, dozens have died in Texan floods, hundreds in an Indian heat wave, and thousands in a Syrian war provoked, in part, by drought. The future looks even more alarming. The IPCC and WMO have both warned that the world, and our place in it, may be almost unrecognizable in a century. So why is there no climate change museum? Granted, most natural history museums have exhibits dedicated to climate history and global warming. The Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D. C., for example, features a spectacular exhibit that links climate change to the fate of early hominids (above). The American Museum of Natural History in New York has an alcove just beneath the Hayden Planetarium that describes global warming and explains how scholars reconstruct past climates. But no permanent museum gathers all of this information in one place, in a way that skips over disciplinary boundaries and alerts the public about the importance of action, today. Miranda Massie and a group of like-minded experts are trying to change all that. Massie is the executive director of the Climate Museum Launch Project. Her initiative seeks to open a climate change museum in New York City, which she hopes will attract some one million visitors per year. We are delighted that she took the time to answer our questions.  Dagomar Degroot (DD): In a nutshell, what is the Climate Museum? Miranda Massie (MM): A climate solutions-focused museum with compelling, interactive exhibits in tourist-accessible New York City. There are two basic reasons for creating such an institution, both arising out of the enormous importance of climate change. First, in intellectual and cultural terms, it’s hard to think of a richer or more interesting subject for a museum. Climate change cuts across a huge range of disciplines and subject areas: many branches of science, of course, and also history, public health, conservation, social justice, psychology, art, and ethics, to name some of the most obvious. Second, and this is what inspires our team to take on a project of this magnitude, we believe that such an institution is uniquely fit to broaden climate engagement, and that an engaged public can generate the climate initiatives needed for humanity to flourish. The museum will break down cognitive and emotional barriers that have helped prevent the formation of a broad climate public. It will concretize climate science through immersive, sensory exhibits; serve as a hub for climate art and dialogue; inspire confidence by showcasing successes; and create a sense of connection and community. The Climate Museum will incubate shared optimism, determination, and enterprise on our most critical challenge. "An engaged public can generate the climate initiatives needed for humanity to flourish." DD: You were a PhD student in history at Yale. You became a lawyer who fought for the marginalized and dispossessed. How has your background equipped you to present the science of climate change in a new way? MM: I don’t think it has! We have a running list of exhibit ideas, but overall my thoughts on our programmatic content are quite general: it has to be solutions-focused, varied, highly engaging, and community-building. That’s hardly a blueprint. Instead, fresh and immersive presentations of the science will be the province of a team of scientific advisors, climate communications experts, exhibit designers, and curators, talent pools we’re exploring. One of the most rewarding aspects of this project is meeting so many gifted specialists—almost all of whom have responded with generosity and enthusiasm. On the other hand, I do think my background has prepared me for this work in other ways. Studying social history and prosecuting civil rights claims taught me that community participation can solve seemingly intractable problems. The latter also exposed me first-hand to the courage and resolve of unsuspected heroes. Both showed me we can win. DD: A recent New Yorker article claims that Hurricane Sandy convinced you that climate change was more than a middle class issue. Do you think the hurricane has helped – or will help you – find support for the museum in New York? Does that say anything about how the public understands climate change? MM: Over time, I came to see climate change as at once the ultimate social equality issue and a categorically distinct and overriding threat to human well-being. Sandy transformed my unease over not working on it into sharpening distress. As for Sandy and support, yes—I think Sandy is one of the key reasons the museum will happen. It changed how New Yorkers think and feel about climate change. It’s a priority for us now in a different way. There are other factors too, of course, including the leadership of the Bloomberg and now De Blasio administrations on climate, the effective work of many advocacy organizations and individual activists, and the joyful success of the climate march last fall. But Sandy was key. And that does say something about how we understand climate change. It’s easier for us to relate to discrete weather events than it is to long-term trends, risks, statistics, and the like. Climate science didn’t change the day after Sandy, but many New Yorkers’ feelings about it did. This is partly an American dynamic. Even leaving aside climate denialism, science and science education have been put under strain in the US, intensifying the intimidating and opaque quality of climate science (as compared to weather experience). But it’s also a human dynamic. We’re first physical creatures, then social and emotional ones, and then only on a good day, at least speaking for myself, intellectual ones. It’s one of the reasons a museum can be such an effective means of connecting with people on climate. It will contain the right information pyramid. This is very much a museum about resilience, adaptation, and mitigation—about our shared ability to escape the danger our shared abilities and proclivities have created. DD: Will your museum explore how humans have evolved with climate change, from prehistory to the present? Or will this be a museum of global warming? MM: The main focus will be on solutions to anthropogenic climate change, with concentric circles of context. One of those circles will be devoted to the history of the planet’s climate and its relationship to life, including human life. DD: To what extent will disaster and decline – keywords in the quest for action on global warming - play a role in your museum? MM: While we must be honest about growing risks, this is very much a museum about resilience, adaptation, and mitigation—about our shared ability to escape the danger our shared abilities and proclivities have created. DD: How close is the Museum of Climate Change to becoming a reality? What still needs to be done? How can people help? MM: Much closer than it was when we started fifteen months ago, with longer left to go. We’ve gotten as far as we have because so many people have offered support and expertise, and we very much welcome more. It is a huge help for people to spread the word through social media and in person. And we gratefully welcome your readers’ further thoughts on how we can, with their engagement and support, get closer to the red ribbon moment. I can be reached at [email protected]. This autumn, we are launching a climate change podcast series. Our podcasts will be shared and transcribed in this space. Stay tuned for details.

|

Archives

December 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed