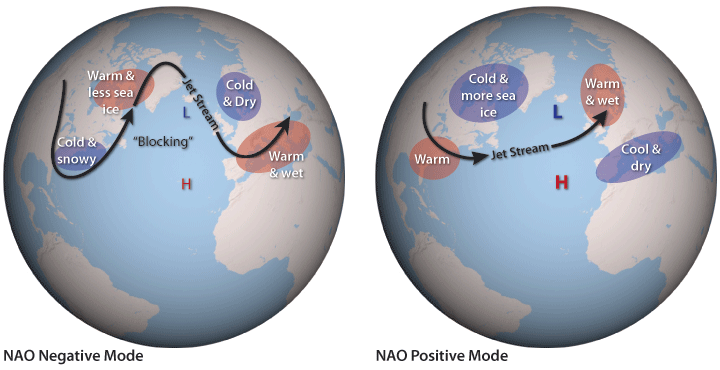

Bruce Campbell is a highly respected historian of medieval economic history whose research and teaching has bridged many disciplines in the sciences and humanities. In his long and distinguished career at Queen's University, Belfast, he has belonged to the Departments of Geography, Economic History, History, and the School of Geography, Archaeology and Palaeoecology. Recently, he published a major new book: The Great Transition: Climate, Disease and Society in the Late-Medieval World. The book transforms how historians have understood the quintessential crisis of Western society - its apparent collapse in the fourteenth century - by rooting it in environmental forces that include climate change. We are grateful to Professor Campbell for answering our questions. Professors Bathsheba Demuth, Dagomar Degroot, and Tim Newfield all contributed to them.  HC: For people who haven't read your book, what is the "Great Transition" your title refers to? What makes the fourteenth century so pivotal? BC: The title of my book refers to the unraveling of one inter-linked pan-Eurasian system of commerce connecting easternmost Asia with westernmost Europe (the system which allowed Marco Polo, his father and uncle, to travel from Venice to Beijing and back) via the caravan routes across the Middle East, and the birth of another based on the newly discovered sea route round Africa, from which eventually sprang Western Europe’s rise to global economic hegemony. At the same time populations were greatly reduced, economic activity was scaled down, commerce was realigned and political and religious boundaries were redrawn. Nor was this all, for the atmospheric circulation patterns of the Medieval Climate Anomaly gave way to those of the so-called Little Ice Age and the Second Pandemic of Plague erupted and spread throughout the greater part of the Old World. It is the multi-dimensional and inter-linked character of these developments that made this extended transition so "great," plus the fact that no part of the Known World remained unaffected. In this unfolding human and environmental saga the fourteenth century is pivotal because it marks the point of no return, when changes in climate, disease and society accelerated and became irreversible. This makes the century one of the most complex and fascinating in history, when the trajectory of change was altered in ways that determined the course of historical development for centuries to come. The fourteenth century is pivotal because it marks the point of no return, when changes in climate, disease and society accelerated and became irreversible. HC: One of the major contributions of the book is that it forcefully argues for connections between disease, conflict, and climate change, in ways that are rarely (if ever) deterministic and rely on some cutting-edge scholarship to show how these factors worked hand in hand to unravel the fabric of medieval Europe. How do you see these three calamities - disease, conflict, and climate change - as connected? BC: I am glad that you think the interpretations advanced "are rarely (if ever) deterministic." Certainly, my aim in writing the book was to eschew all forms of determinism, including those that stem from too exclusive a reliance upon economic models of historical change. Of course, climate, disease and society all had their own separate dynamics hence it is often more helpful to think in terms of conjunctures than connections, as expressed by the idea of a perfect storm, when several separate developments coalesced at the same point in time. But connections there certainly were, as articulated via the complex web of inter-relationships that connected humans and the natural world. These are the socio-ecological systems referred to in the book with their component elements of climate and society, ecosystems and biology, microbes and humans. HC: Did the presence of one of these elements - the climate, the pathogens, or the social changes - make some of the others more likely? Can we see similar relationships at other points in human history? BC: The answer to both questions is yes. How human events unfolded over the course of the fourteenth century would have been entirely different in the absence of climate change and, especially so, in the absence of plague. Each element of this destabilising scenario compounded the effects of the others. For parallel situations at other points in human history look no further than Geoffrey Parker’s Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century (2013) and John L. Brooke’s Climate Change and the Course of Global History: A Rough Journey (2014). The latter shows that crises of this sort have recurred throughout human history. If we broaden our analytical remit they come more clearly into focus and enrich the historical narratives we have to tell. HC: You note the increase in climate variability in the fourteenth century. Do you see some societies as having adaptations that made them better able to deal with this instability? BC: Away from environmental, political and military margins, Western Europe proved to be remarkably resilient to the increase in climate variability in the fourteenth century. Admittedly, there were stresses and strains and subsistence crises and famines, occasionally, as in the case of the Great Northern European Famine of 1313‑21, on a grand scale, but no tipping point was reached until plague (Yersinia pestis) intervened. In large part this was because of European agriculture’s intrinsically mixed-farming character, with its variable combinations of arable and grass, interchangeable choices of crop types and livestock types, and extensive use of working animals. Properly managed, these were innately sustainable farming systems and even quite serious short-term setbacks, as in 1315-21, could be quite quickly overcome. It appears to have been otherwise in the case of the irrigation-based rice-growing farming systems of China and southeast Asia, with their narrower range of crops, far smaller pastoral sectors, and heavier dependence upon human labour. For them the failing reliability of the Asian Monsoon from the late thirteenth century proved to be far more challenging and destabilising than anything that northwest Europe had to cope with. The scope for comparative research into these kinds of issues is considerable. HC: Disease also plays a huge role in your work. That the black plague reshapes demographics is something familiar to many historians, but you go into detail about how the "socio-ecological" context of the mortality crisis affected European responses. Can you explain what work the term "socio-ecological" does for you, and what kinds of variation it accounts for? BC: Analysis of ancient DNA has now established beyond reasonable doubt that Yersinia pestis was the pathogen responsible for the Black Death of 1346-53. The bacterium is still active in the world today and, in fact, plague deaths are on the increase, especially in such countries as Madagascar and in plague’s ancient reservoirs of Central Asia. This is attracting a great deal of serious scientific research that has revealed the range of wild mammalian hosts capable of harbouring the infection, the vital role played by fleas and maybe even lice in spreading it, the susceptibility of both to climate-driven variations in ecological conditions, and the role played by levels of human exposure to the relevant insect vectors in determining rates of infection. Plague, in fact, is one of the most ecological of all diseases, but it is also closely associated with human poverty and patterns of mobility and communication. It was much the same in the late-thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. What I have attempted to show is that to understand the origin and spread of the Black Death it is necessary to reconstruct this web of socio-ecological relationships. Recent progress on this front has been impressive but there is still a great deal more to be learned. HC: What do you think about the recent historical and palaeomicrobiological scholarship that suggests the plague bacterium established enzootic foci in Europe after the Black Death? How does this affect our understanding of late medieval and early modern plague? BC: The jury is still out on this one. One school of thought believes that, impelled by short-term climate shocks, plague was repeatedly reintroduced to Europe from reservoirs of infection in Central Asia, although so far only the initial outbreak that started in the Crimea in 1346 has been tracked in detail. Alternatively, it has been hypothesised that semi-permanent reservoirs of infection became established in Europe, either among urban colonies of rodents in the greatest ports and cities or in their ground-burrowing sylvatic cousins, such as the Alpine marmot. After all, in most parts of the world where enzootic plague foci have become established, it is wild mammals in thinly populated rural areas that maintain it. In such cases, as exemplified by Madagascar, small mutations soon promote the evolution of geographically-specific lineages of the Yersinia pestis genome. The proof of whether or not enzootic plague foci became established in Europe will therefore hinge upon whether aDNA analysis can identify specifically European variants of the genome. So far no such evidence has been found, but then these are still early days for this most expensive branch of bio-archaeological research. The answer is important because it bears upon the ability of medical historians to explain how plague seemingly managed to sustain itself in Europe for so long, especially given the long intervals between some outbreaks, why it eventually disappeared, and the extent to which plague outbreaks in Europe were driven by fluctuating environmental conditions in Central Asia. For historians of plague these are the big questions to which satisfactory answers have yet to be found. Meanwhile, there is plenty of more conventional historical research to be done, tracking the course and estimating the impact of the second outbreak of plague in 1360-63, and improving upon Jean Biraben’s pioneering chronology of European plague outbreaks. HC: New reconstructions of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) have challenged previous reconstructions that showed a persistently positive NAO during the Medieval Climate Anomaly, and a negative NAO in the centuries that followed. The scientific state of the art can change much more quickly than the historical state of the art. What does that mean for histories that draw equally from scientific and documentary evidence? BC: Keeping up with the advances in knowledge being made by climatologists and biologists is a real challenge. Medieval historians have not been idle but, you are right, the historical state of the art changes much more slowly. This discrepancy will certainly keep us on our toes and engender a constant process of iterative rethinking. It will also make study of the medieval centuries more dynamic, pertinent and exciting. Above all, it challenges us to come up with more and better historical databases and chronologies to enable more rigorous analyses of the interactions between environment and society. In this context, it should not be forgotten that historical archives contain a rich trove of information that can be deployed to shed light on past environmental conditions. Of course the histories we write using the imperfect information available today will soon need to be revised and certainly will eventually be superseded, but this should not deter us from writing them. The histories we write using the imperfect information available today will soon need to be revised and certainly will eventually be superseded, but this should not deter us from writing them. HC: Your background is as a Medieval economic historian specializing in England, if I'm correct. How did you move to write a global environmental history?

BC: In fact, my initial training was in geography, which required me to think comparatively and on a large scale and pay due attention to environmental and human agencies and processes. My doctoral research then focused in on three exceptionally well-documented medieval Norfolk manors. This was when I started using manorial accounts to measure crop yields and using manorial court rolls to chart the influence upon the market in customary land of years of dearth and glut. This work left me in no doubt of the magnitude of the impacts upon these crowded and impoverished rural communities of the terrible harvest failures of 1315‑17, the great cattle panzootic of 1319 and, above all, the outbreak of the Black Death in 1349. Back in the early 1970s it seemed to me that none of the then current historical models was capable of accommodating the environmental dimensions of these disasters. Nor had the detailed climate reconstructions been undertaken that would have allowed me to place these events in their broader socio-ecological context. But my interest was aroused and the proxy climate series are now available that have enabled me to write what is intended to be less a global environmental history than an economic history of a formative era, taking full account of the contribution made by global environmental process. Of course, in 2010 when I began this book project I had no idea that it would lead me to ponder the influences of varying levels of solar irradiance upon ocean-atmosphere interactions in the Pacific Ocean or those of alternating droughts and pluvials upon the enzootic foci of plague in Arid Central Asia. The academic challenge of so doing has been daunting, occasionally almost overwhelmingly so, but it has more than repaid the effort and the book will, I hope, encourage others to challenge its findings and take the subject and this approach further. HC: Do you see any lessons from this period for the present? BC: History, as we know, never repeats itself but there are always lessons to be learnt from it. The serious risks posed by climate, disease and conflict have not gone away. What the ‘Great Transition’ demonstrates is the intrinsic instability of climate systems, the weather extremes that can materialise seemingly out of the blue, the punitive power of microbes when unchecked by science, the economically disruptive impacts of armed conflict, and the sheer bad luck of several extreme events occurring at much the same time. Above all, the fourteenth century shows that the status quo of centuries can be overturned.

5 Comments

For the fourth episode of the Climate History Podcast, Dr. Dagomar Degroot interviews one of the world's leading environmental historians: Dr. John R. McNeill of Georgetown University. Professor McNeill has authored or co-authored six books, and edited or co-edited twelve. He is perhaps best known for Something New Under the Sun: An Environmental History of the Twentieth-Century World, which won the book prizes of the Forest History Society and the World History Association. He also wrote Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1640-1914, which was awarded the Beveridge Award of the American Historical Association. McNeill has authored or coauthored well over 50 articles in journals that span the scientific and humanistic disciplines, ranging from Science to Environmental History. He is a past recipient of a MacArthur Grant, a Toynbee Prize, and a Guggenheim Fellowship, among many other awards. In this episode, Professors Degroot and McNeill discuss the "Anthropocene:" the proposed geological epoch distinguished by humanity's profound transformation of Earth's environment. McNeill is currently a member of the Anthropocene Working Group for the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy. This body of experts recently recommended that International Union of Geological Sciences consider the Anthropocene a new geological epoch, with a starting date of around 1950. Professor Degroot therefore asks Professor McNeill about alternative starting dates, criticisms of the Anthropocene concept, and the special place of climate change in debates about humanity's recent reshaping of the Earth. To listen to this episode, click here to subscribe to our podcast on iTunes. If you don't have iTunes, you can still listen by clicking here. |

Archives

December 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed