Has climate's sensitivity to CO2 been overestimated? November 25, 2011.

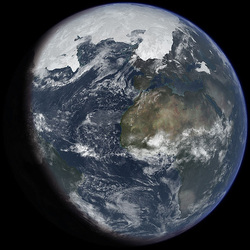

Rendering by Thomas J. Crowley, 2010.

A new study published in the journal Science by lead author Andreas Schmittner has used paleoscientific data to argue that the last Ice Age was not as cold as previously thought. That, in turn, suggests that global temperatures are less directly linked to atmospheric carbon dioxide than previously believed. The article, which has received extensive media attention, claims that a doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide from pre-industrial levels would lead to a rise in the world's temperature of 1.7-2.6 degrees Celsius. In another article published in the same issue of Science Gabriele Hegerl and Tom Russon caution that Schmittner and his fellow researchers have developed just one model, and further research is required to support their results. As reported by the BBC, Climatologist Andrey Ganopolski also cautioned against reading those results as definitive, warning that the relationship between carbon dioxide and global temperatures is probably different during colder periods than in warmer decades.

Ultimately, it is difficult to know what to make of these results. The idea of "using the past to predict the future," as Hegerl and Russon put it, is doubtless appealing to many historical climatologists, but the notion of unproblematically linking past temperatures to past CO2 concentrations seems simplistic when so many possible climatic stimuli exist. At first glance it seems better to use sources from both cooler and warmer periods in the less distant past that can also be supplemented with documentary evidence. Meanwhile, although the authors contend that their study does not reduce the need for urgent action to mitigate global warming they do claim that their results suggest a "lower probability of imminent extreme climatic change than previously thought." That attitude is worrisome given the upheaval the accompanied, for example, the most extreme phases of the Little Ice Age - when temperatures probably did not drop as much as 2 degrees Celsius below their previous average - and the sensitivity of modern agriculture to climatic fluctuations. Either way it's telling that the first scientific assessment to uncover links between modern extreme weather events and global warming - also described in the latest issue of Science - has not received nearly as much press.

Ultimately, it is difficult to know what to make of these results. The idea of "using the past to predict the future," as Hegerl and Russon put it, is doubtless appealing to many historical climatologists, but the notion of unproblematically linking past temperatures to past CO2 concentrations seems simplistic when so many possible climatic stimuli exist. At first glance it seems better to use sources from both cooler and warmer periods in the less distant past that can also be supplemented with documentary evidence. Meanwhile, although the authors contend that their study does not reduce the need for urgent action to mitigate global warming they do claim that their results suggest a "lower probability of imminent extreme climatic change than previously thought." That attitude is worrisome given the upheaval the accompanied, for example, the most extreme phases of the Little Ice Age - when temperatures probably did not drop as much as 2 degrees Celsius below their previous average - and the sensitivity of modern agriculture to climatic fluctuations. Either way it's telling that the first scientific assessment to uncover links between modern extreme weather events and global warming - also described in the latest issue of Science - has not received nearly as much press.