|

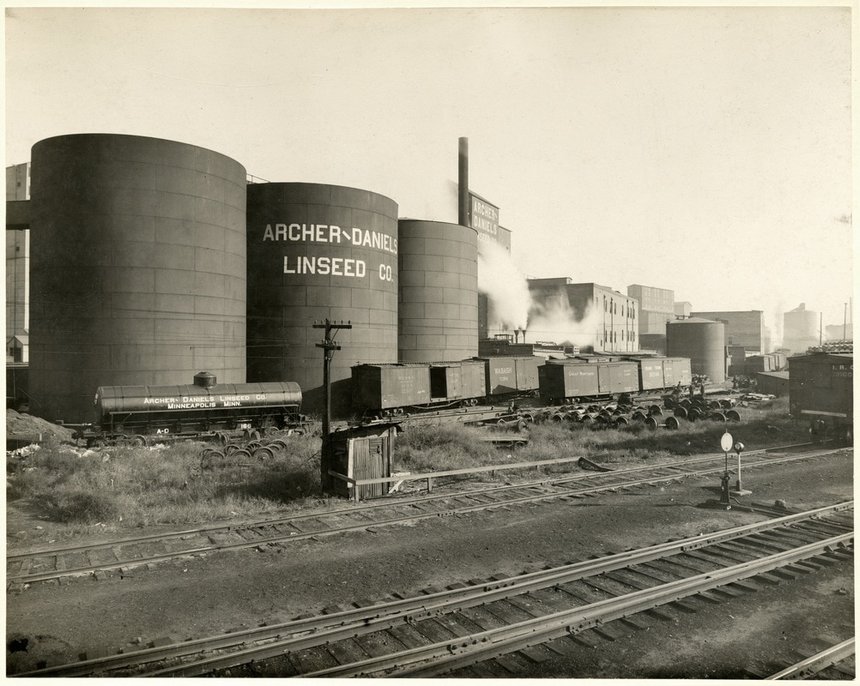

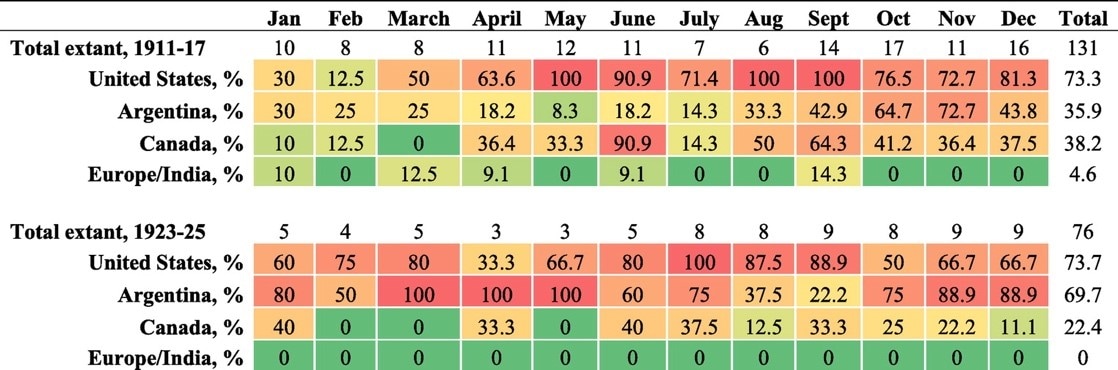

Dr. Josh MacFadyen, Arizona State University When Monsanto spent $1 billion in 2013 to purchase Climate Corporation, its climate data, and its algorithms for using machine learning to predict weather, everyone from farmers and insurance companies to technologists and The New Yorker concluded that agri-business believed the climate science consensus: climate change is real and it introduces real risks to business. One century earlier, another major Western agri-business (Archer-Daniels-Midland or ADM) produced their own cutting-edge weather and crop forecasts, mainly in an effort to reduce the risk of what it called “weather markets.” By investing in environmental knowledge production, these companies revealed how they understood both local environments and international climate sciences. Historians know a great deal about early amateur and state organized meteorology and climatology, and a range of new works are emerging on the science of forecasting. However, the climate looks different when we examine it from the private sector. Business historians do so using company records and within the context of the firm. My study of the economy of knowledge in agri-business focuses on Archer-Daniels-Midland Linseed Company (ADM), a notoriously secretive company that started in Minneapolis and has since become one of the big five multinational firms in the agrifood sector. Its primary interest in the early twentieth century was not the highly-processed corn and soybean commodities it is known for today. Rather, ADM specialized in another oilseed altogether – flax. Flax had changed from a European crop grown for linen to a predominantly American crop grown in the temperate grasslands of the northern Great Plains and the Argentine Pampas. It was produced mainly for its seed (linseed), which was pressed to make linseed oil, the principal ingredient in paint. Flax was very popular with farmers in the northern Plains, because it matured quickly and could be planted on newly broken fields on the frontier. ADM had relocated to Minneapolis precisely because of this growing western supply chain. When they got there, they realized they had a lot to learn about anticipating the weather and forecasting production in this harsh new environment. The history of ADM’s response to price volatility, supply chain problems, and trade policies tells us about the way businesses understand climatology and develop environmental knowledge. Like the Climate Corporation, ADM was predominantly concerned with risk mitigation. And where there was risk there was profit. The linseed oil business included some of the leading names in the chemical sector, including Lyman Brothers in Montreal, the Rockefellars’ American Linseed Oil, Sherwin Williams, and Spencer Kellogg and Sons. These companies were major players, and they purchased flax seed from for their oil and paint operations from whatever part of the world would supply it. In the late nineteenth century, that was predominantly the northern Plains, but in the early twentieth century they found emerging markets in Argentina, Uruguay, and some older flax producing regions in Eastern Europe and India. As a relative upstart, ADM found a niche in the globalizing industry by providing crop and other environmental information to the trade. The big players bought flax seed and flax seed futures in a massive grassland frontier (the Northern Great Plains, the Canadian Prairies, and the Argentine Pampas) with limited knowledge of those regions’ agroecosystems and even less about their climates. This article argues that crop knowledge was extensive and growing in the late nineteenth century, but climate knowledge was limited and retreating, because of underfunding and spurious theories about solar radiation. Meteorological forecasts were only good for 48 hours, and although Farmer’s Almanacs were very popular, their forecasting methods were secretive and studies have shown that they were really no more accurate than a coin toss. In my study, I make two other conclusions based on a content analysis of the firm’s semi-public market reports circulated between 1911 and 1925, with a five-year gap starting in 1918. The first is that ADM created an early version of the Climate Corporation, focusing its attention on the growing conditions and probable outcomes of the flax crop. The records show that the company virtually ignored the European and Indian crops, knowing that those would likely enter UK markets before reaching their North American clients. Most of their weekly synopses were about crop conditions in the northern Plains, drawing from a network of crop agents, elevator companies, and other intermediaries such as state flax scientists. However, their interest in Canadian conditions decreased, and they increasingly focused on Argentina over this period. By the 1920s, ADM was reporting on Argentina almost as frequently as it mentioned the US. The second finding was that the futures markets were more closely connected to natural systems than some historians of these “incorporeal” commodities have argued. Information systems like ADM’s circulars developed almost real time networks of crop and climate knowledge, but after a certain point these agri-businesses, conceded that futures trading was “purely a weather proposition.” Commodity futures became highly risky as overlapping harvest seasons approached, linseed oil producers depleted their reservoirs, and buyers attempted to determine which crop and weather forecasts were most tenable. This is precisely where we would expect to hear corporations arguing over comparative meteorological systems and the reliability of Almanacs, but these topics were almost never mentioned. ADM realized that in the period between sowing and harvesting, the price of flax was “a weather market.” Their records show that businesses in the grain and oilseed sector created extensive knowledge networks to gather crop and some climate information in almost real time. Unlike the meteorological offices or the almanacs, ADM aimed for the respect of a much smaller business circle, and they therefore maximized data and minimized predictions. They mentioned US weather in about half of their circulars (less for other countries) and they predicted weather in very few of those cases. They were more bullish with crop forecasts, but the circulars show that they rarely reported weather forecasts. The weather that they did report was current conditions, and it was mainly in regards to the Northern Great Plains crop during the critical maturing and harvest months (June–September). As my longer article on ADM’s response to uncertain climates outlines, the company was deeply invested in place, and its business decisions were shaped in part by its longer commitment to the Northern Great Plains. Its larger role in the knowledge economy was influenced by its position on crop and climate science; the company distrusted government crop forecasts and disregarded meteorological forecasts. ADM’s respectability depended on accuracy, but as the almanacs (and recent politicians) show, you don’t need to be accurate to be popular. When agri-business ignored early twentieth century climatologists and created their own knowledge products, they signaled a distrust in science that proved to be well founded. In recent decades, we are seeing a completely supportive message from the private sector. Business signals its knowledge about the environment at many scales, from local family farms to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. When Reagan-era Secretary of State, George P. Shultz, and Climate Leadership Council president, Ted Halstead, recently advanced what they call The Business Case for the Paris Climate Accord, their message was simple. Since top US businesses support the Paris climate agreement, Donald Trump should embrace the broad consensus of climate scientists and remain at the table in Paris. Granted, their argument ignored the ethical and other humanitarian reasons for stopping runaway climate change and mitigating the harmful effects it will have on the biosphere, but when even corporations like Monsanto are spending billions to mitigate the risks associated from climate change it’s time politicians listened to the deafening message coming from all sectors. Joshua MacFadyen, “Long-range forecasts: Linseed oil and the hemispheric movement of market and climate data, 1890–1939,” Business History 59:7 (October 2017). Published online, April 2017. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2017.1304915

Did. A young woman dressed up in a red rust Comments are closed.

|

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed